“Take your heart wherever you wish in [search of] love, but it will always be in the hands of your first love; many are the places one resides in, yet he forever longs for his first home.” (Abu Tammam)

My story unfolds. Life takes me wherever it wishes and throws me in every direction—its ebbs are flows. Life goes on, and features of faces change, just like the places where I live. When I grow tired, my imagination takes me back to my house in Damascus. It is there that I feel comfortable. The house comprises of five big rooms and two spaces that we use for sitting, eating, talking and watching television. We call them the big and small salons. The house also boasts two balconies—a small one with its door in my room and a big one, where we sleep in summer, with its entrance in the small salon.

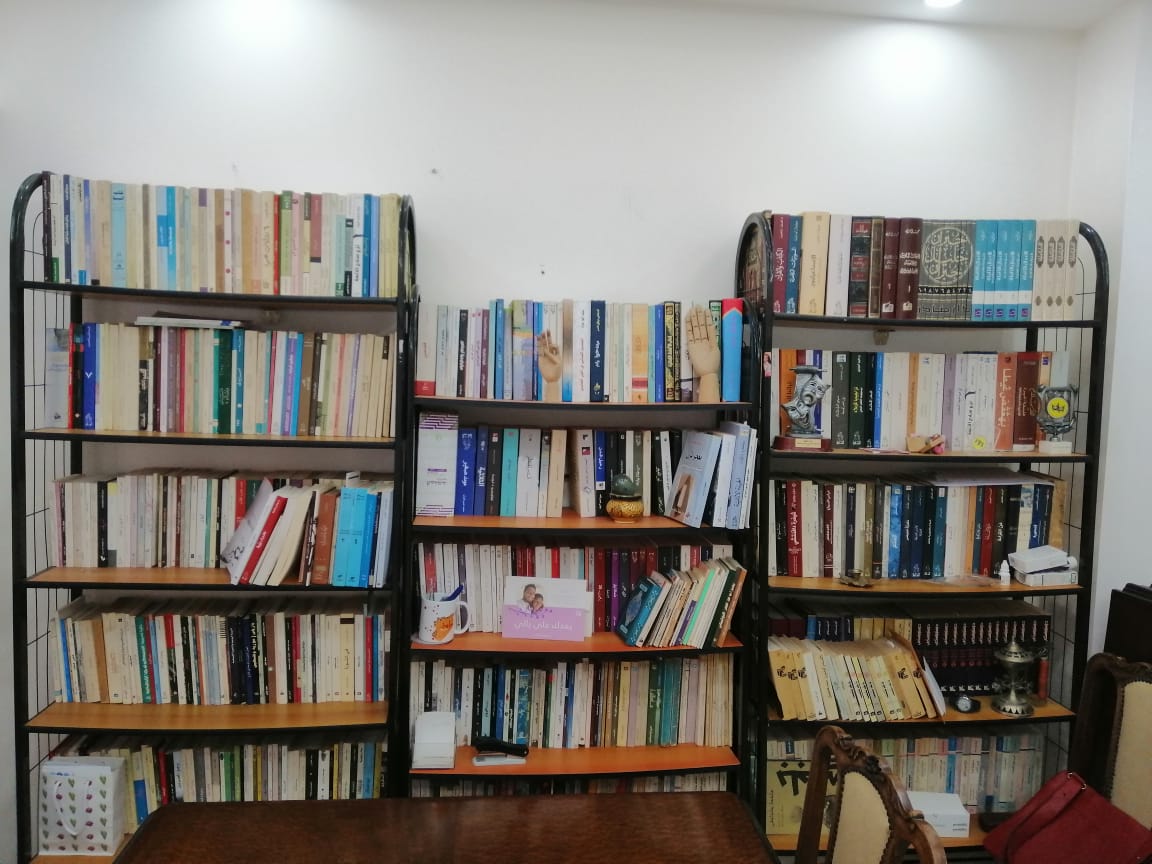

We share the rooms of the house my grandfather built. One of them is the library, which was previously my uncle’s room, and before that, his brother’s room, and earlier, another brother’s room. However, no matter how much its occupants changed, the room has always been reserved for books. Most of these books were for my uncle who was a translator (Haval Youssef), while others were for my brother who left the country years ago. My mother and father also had their share, as did my uncles who migrated successively, as of the early 1980s. Ultimately, my grandmother was the only one visiting the house occasionally and contemplating the forsaken library nestled in dust.

It is in this library that I started reading. I was eight or nine when I read Arsène Lupin, Gentleman-Cambrioleur [Gentleman-Burglar]. Then, I embarked on an endless reading journey, like the Tigris and Delta rivers that tirelessly flow; crossing countries and kingdoms and experiencing battles and events without [their waters] being affected. This was my first library— the family library that became my own. I wanted to talk about it and about other ones I lost. I wanted to recall my first memories, in the hope that they might help me get through my days. After Damascus, I had a small library in Cairo, and I moved it with me to Beirut where I expanded it. Many books were lost during my various moves. In Berlin, I built my library, which I take care of religiously. But, occasionally, I reminisce about Damascus, the house in Damascus and the library in Damascus. I wanted to talk about this library, but it is not my story to tell. It is the story of the whole family. So I told myself, “Why don’t I ask my uncle who had the biggest share of books? Why not dig up those shared memories?”

A library in Damascus and grief over lost manuscripts

My uncle, Haval Youssef (50), who lives in Beirut and translates from Russian, sent me a Whatsapp message to answer my questions. He said, “I contributed to building three libraries in my life. The first was in the Soviet Union and included books published mostly by Dar al-Taqaddum Publishers and Raduga Publishers.”

That was his shared library with his Kurdish roommate in one of the student dorms in Leningrad. He and his friend who was an avid reader would visit Moscow every few months to drop by Dar al-Taqaddum and take what they could from the books.

Youssef said that the writings of classic Russian authors like Maxim Gorky, Tolstoy and Chekhov, among others, occupy the biggest space in the library.

After we left the country and resided elsewhere, the books seemed sad, and dust covered them. My grandmother felt this sadness for her children, grandchildren and their books. She cared for the books, although she would always jokingly say, ‘If I had a kiln, like in the old days, I would have burnt all your books.’ My grandmother kept the books in cartons to preserve them,” Haval told SyriaUntold.

Over five years, the two young men established a large library, and when they left the Soviet Union and returned to Syria, they left the books with some friends, on condition that they would give them to a student committee later. My uncle does not know what happened to these books, after he settled in Damascus.

At the time, our library or the family’s library comprised of my grandfather’s religious and historical books, biographies of leaders and my father’s books — my father who read what was popular in the 1970s like books by Naguib Mahfouz, Toufic Hakim, Ihsan Abdel Quddous, Youssef Idriss and Victor Hugo.

When my uncle who is a book collector returned to Syria, he continued his reading journey.

“I buy more books than I can read. That is how the family library grew and became what it is today. My siblings and I grew up here, and we loved to read. We bought books, and the library expanded. After we left the country and resided elsewhere, the books seemed sad, and dust covered them. My grandmother felt this sadness for her children, grandchildren and their books. She cared for the books, although she would always jokingly say, ‘If I had a kiln, like in the old days, I would have burnt all your books.’ My grandmother kept the books in cartons to preserve them,” Haval told SyriaUntold.

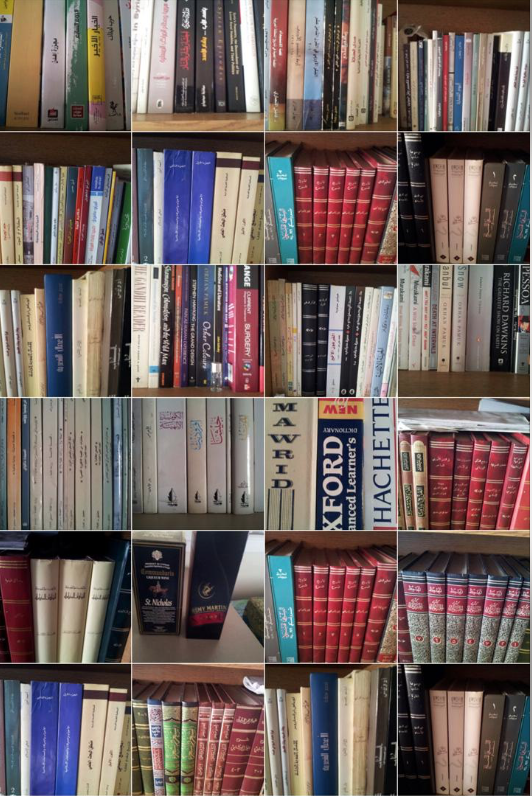

Nine years ago, my uncle left Syria for Lebanon. He married a Lebanese woman who loved to read and who had a library, which was the third one he helped expand. Their library became stacked with books.

This is how Youssef contributed to building three libraries in three different countries, because a library is central in his life. His library extracts importance from the books it contains. He told me, “You should ask me about the importance of books and reading in a person’s life rather than the importance of the library.” He spends long hours each day reading, and he lives more with books than anyone or anything else. His work in translation and editing helps him in this sense.

Youssef says, “Reading improved my Russian and Arabic, and I managed to work in translation, writing and editing. Without reading, none of this would have happened. The library is integral in my personal life, just like sleeping, drinking and eating. When I do not read, I feel sick, as though I did not take the necessary medication for my survival.”

Youssef said that a library at home indicates the owners’ line of thought and lifestyle. He added that his eyes search for the library, as soon as he enters a house for the first time. When he does not spot any books, he feels as though he is walking in the desert and wonders, “How can these people live without reading?”

I asked him about our library in Damascus once again. He said that he does not feel bad about many books because he can buy them again, but he is mostly devastated over manuscripts.

He explains, “My father wrote a manuscript with his own handwriting, and I promised him to publish it after his death. But, the war broke out, and the manuscript remained in Damascus.”

Also in Damascus, there were two manuscripts for two books that Youssef translated but has not yet completed. He is mostly upset over some rare copies that are unavailable now and over books that were special dedications from their authors.

Raid Wahsh: 'The library is my identity'

I wanted the story to include other libraries. I asked my friends about their libraries and books. I sent a short Facebook message to my friend, the poet Raid Wahsh (37), who lives in Hamburg. I said, “I want to write a story about libraries we left behind. I remember our discussion about your library in Khan al-Shih in Rif Dimashq. Can I ask you a few questions about libraries?”

Raid answered my questions enthusiastically, saying, “I support any cause related to books.”

I asked, “Why? What is the importance of the library in your life?”

He said, “The library is my identity.”

In an email, Raid wrote, “Reading allows a person to carve his identity and to fight social media, which have been giving us a new identity. Reading is a form of resistance at a time when tools to control our minds, thoughts and inclinations are rife. But, not all reading is useful. Many readings are at the mercy of the consumerist trend. When I say reading, I mean cognitive and strategic reading that refuses to cave in to superficiality, control and all that is mainstream.”

I asked, “Raid, how was your library established? How did you collect the books it includes?”

He answered, “Honestly, although the questions are simple, they are exciting. One cannot answer without bringing up what they read, book by book and page by page.”

Raid cannot imagine a house without a library. It is a principle that grew inside him. The story about building the library never ends. He goes back to the Stone Age, when humans drew on the walls of caves images of the outside world, perhaps to distribute magic powers.

Raid believes his house is like that cave, and the library is like the murals of the cave and its only amulets.

He is now building his library at his home in Germany, despite the hardship of getting Arabic books. When his friends fly from Arab countries, he asks them to bring him books. He buys books from the internet and pays for their shipment cost, ignoring the nuisance of the long wait. He tries to paint the murals with different books; perhaps to compensate for those he left behind in his family home in Khan al-Shih camp. He says, “One of the few reasons I am optimistic now, despite the tough war in the camp and in other Syrian cities and towns, is that my books are fine. Our relatives who live in our house now send us occasionally photos of the library to reassure us. I will tell you a family secret. My parents who never cared about these books insist on the inhabitants of our house to send them pictures. This library is what remains of our house’s meaning. They never read any of the contents of my library, but it is now the last remaining trace of the house. What more could one want?”

In his exile, Raid misses magazines. He says he owned an archive of cultural and intellectual magazines back home, like Al-Karmil, Fosoul, Tareeq, Al-Nahj, Ijtihad, etc.

He continues, “One can struggle to get books from faraway lands, but asking for magazines that are mostly banned is a waste of his and others’ time.”

The library of a refugee

While seeking stories about libraries, I heard the story of the library of poet Fouad M. Fouad (57) who lives in Beirut. Fouad is a surgeon and university teacher at the American University of Beirut (AUB). We contacted him directly on the phone, after several attempts, and I heard his story.

He said he would tell me his story before I asked any questions. I agreed.

He started, “My library is a refugee, like me. Just like people take refuge in other countries, my library took refuge elsewhere too.”

Fouad believes books “are people transformed into words and pictures between two covers. That is why libraries are part of people’s lives. Everybody has written his life story on paper. It was normal for them to remain with us, not necessarily at home, but also in life. Libraries are a necessity for humanity. Libraries enclose people’s lives. Books are not just for education, reading and fun, but they are a living experience. Since people are social creatures, they live with books.” Fouad could not dispose of any books during his life, not even the bad ones. He simply cannot throw away a person’s life.

The first book in his library was Mahfouz’s Zukak al-Midaq [Midaq Alley] when he was 12.

He said, “At 16, owning books became a habit.” He now owns about 8,000 books, which he collected at home then in his clinic in Aleppo, after his small house no longer fit additional books.

The books were distributed between his old house, his new bigger house and his clinic.

Aleppo was destroyed, and people were forced to migrate. Dr. Fouad and his family migrated to Lebanon, leaving behind his books in Al-Manshiya neighborhood, where dangerous clashes took place. He took along the Comparative Encyclopedia of Aleppo by Khair ad-Din al-Asadi, and left the remaining books, in the hope of meeting again.

Books remained his obsession. He wanted to make sure they were fine and bring them to his abode in Beirut, after realizing his return to Aleppo was impossible. One day in 2014, a friend suggested to donate his books to AUB where he works. The AUB library is among the oldest and most important in the Middle East. It was inaugurated in 1866, when the university was founded.

Fouad thought about the condition of the books, and he wanted them to have a safe place rather than remain in a war zone with an unknown future. He did not want his books to die alone. He suggested the idea to the library secretary who welcomed it and said the university would take care of the book transfer.

The university agreed with a transport company to bring the books to Beirut, and the company handled the details of the operation, after talking with one of Fouad’s acquaintances to allow them to enter the two houses and clinic. Meanwhile, some armed men took over his two houses and clinic.

He said, “After deliberations, many security approvals and preparation of lists and disposal of some books that were banned in Asad’s Syria, the remaining books were collected in the car and moved to Damascus. In the process, some books were lost, and others were confiscated at a Syrian army checkpoint, like Al-Jahiz’s Book of Animals and Kitab al-Aghani by Abu Faraj al-Asfahani, in addition to other valuable books.”

Fouad still does not know where the books he lost are.

In Damascus, the family of major playwright Saadallah Wannous had decided to donate his big library to the AUB library.

Fouad said, “The library management agreed with the same transport company, which gathered both shipments together and brought them to Beirut after getting new security approvals.”

The books reached Beirut early 2013 [not sure about the year, typo]. The books of Fouad and Saadallah were mixed together, because neither had a list of his books, nor did their families.

At the AUB library, a corner was dedicated to Saadallah as a token of appreciation for his donation, while Fouad’s books were lost between the other books because he did not agree with the library management to dedicate a corner for him, unlike Saadallah’s family.

He walked around the library, searching for his books. He recognized some of them and held them to his heart, kissed them and cried.

…

I thought long and hard about these stories. I pondered over whether to write about them or not. I wondered how to draft these ideas. After research and interviews, I thought about a way to write the story and about its ending. What could one say at the end of such a story? I did not know. I referred to my chats with friends, and I could not find better than one of Raid’s sayings to conclude with.

“Perhaps the yearnings we experienced in our quest for books are on par with our passionate longing for love. They might even outweigh that longing. But, it seems much is said about the history of love, while silence prevails over the history of reading.”