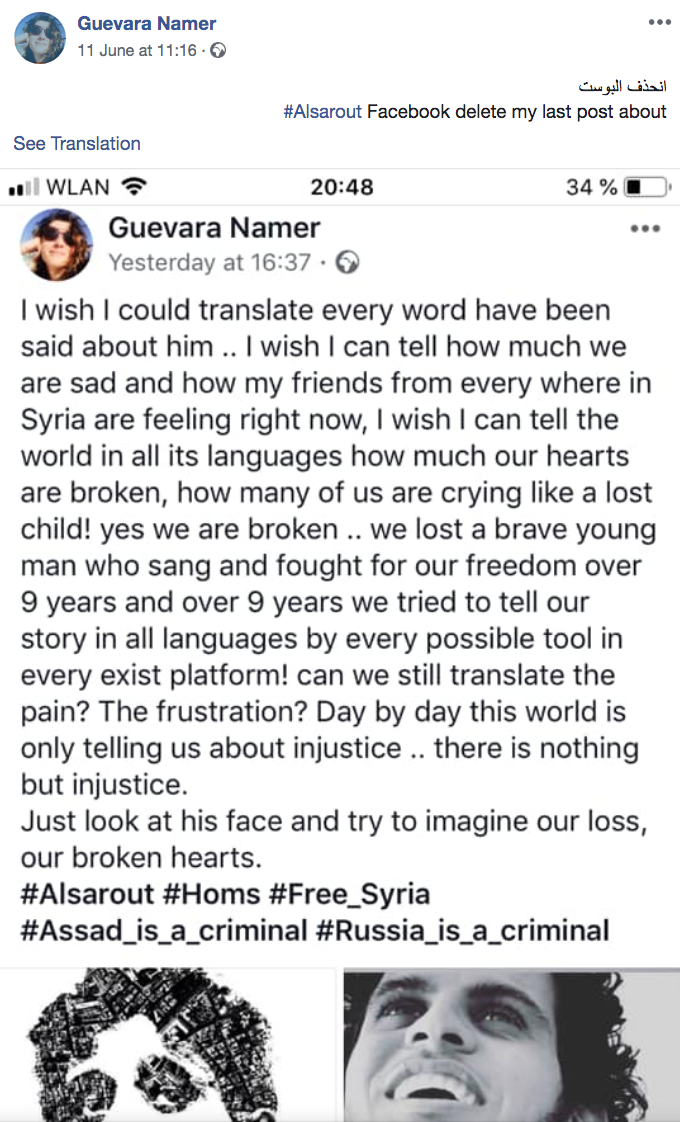

On June 10, Guevara Namer, a Syrian filmmaker based in Berlin received a notification from Facebook that her post, mourning Abdul Baset al-Sarout, an icon of the Syrian revolution who died two days before, has been removed because it “violates Facebook community standards”.

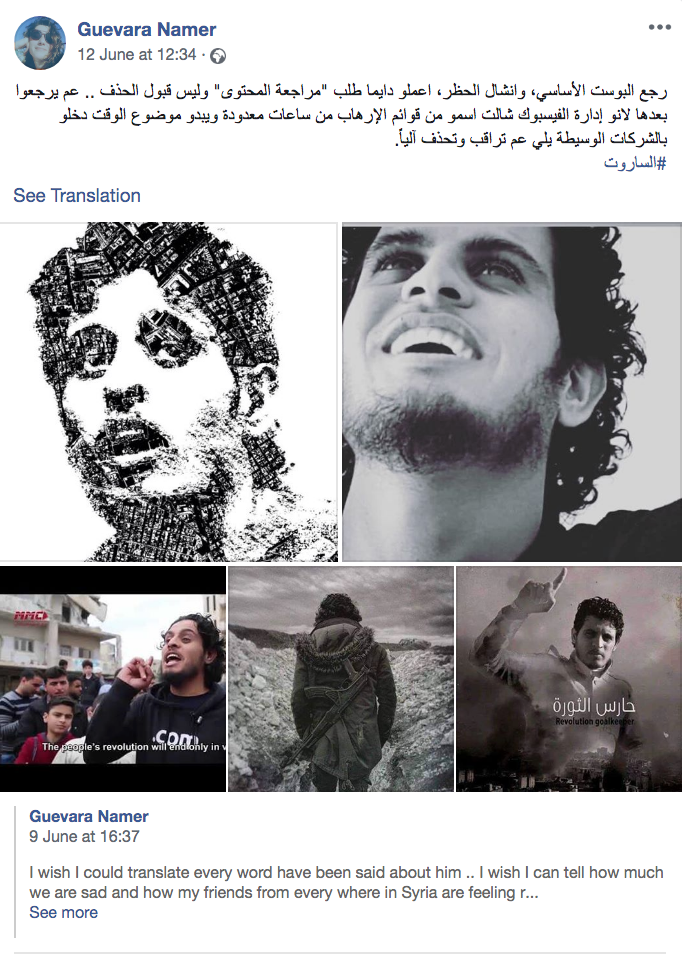

When the Syrian uprising began in 2011, al-Sarout was already well known in Homs as the Al-Karamah SC youth goalkeeper. He soon emerged as a protest leader, the charismatic 19-year-old was fearless, and he led demonstrations singing and chanting. His songs were much loved and motivated many to join the protesters. The regime cracked down, and the uprising turned into a war, al-Sarout became a fighter and a rebel leader. He lived through Homs siege, and after the rebels surrendered Old Homs back to the regime in 2014, he travelled to the opposition-held north where he was fighting at the frontline till his death. While many in the opposition saw him as a revolutionary icon and brave leader, regime loyalists criticized his links to Islamists fighting in Syria, and said he repeated Jihadi songs to indicate he was a terrorist. The war in Syria is not restricted to the frontline, it is a war of narratives, and the symbolism of al-Sarout as an icon was contested when he died.

Al-Sarout was 27-year-old when he died on June 8 in a Turkish hospital from wounds sustained in a strike by the Syrian Army in northern Hama. His death revived massive pro-revolution voices who took to social media, to express collectively their sorrow and loss of a prominent voice and figure in the fighting against Assad’s regime. However, their sorrow has faced attempts of silencing by the giant platform, Facebook.

For Guevara Namer, this was a clear coordinated attack. “When my post was removed from Facebook, I posted about the removal and reposted a screenshot of the post that was removed, this post too, was removed and I was banned from commenting on others’ posts for 3 days. But I kept seeing other posts by people who said their posts about al-Sarout had been removed too, all for the same reason: violating the community standards”, she said.

According to Syrian opposition media, there were hundreds of cases of posts removal or pages/groups shut down including Zaman Alwasl TV or the Forum for Syrians in France page. According to what we could track, most posts were removed on June 9th and 10th, one to two days after the death of al-Sarout. This included posts by Syrian writer Yassin Haj Saleh, Syrian playwright and theater maker Mohammad Al Attar, Syrian actor Fares Helou, Syrian writer and journalist Nisreen Traboulsi and many others.

But they fought back, Namer and others did not only submit “request review” to Facebook, but they kept constantly posting about the ban. For two days, Syrian opposition activists tried to fight against the ban and put pressure on Facebook in different ways including a campaign of massive posting under al-Sarout hashtag and a petition on avaaz signed by over 16,000 people. On June 12th, the ban was lifted and most posts or pages that were closed returned.

This is not the first time where Facebook has helped in silencing Syrian opposition voices. In 2012, Facebook apologized after it mistakenly deleted a free speech group's post on human rights abuses in Syria. In 2014, Facebook closed dozens of Syrian opposition pages, including the Kafranbel Media Center’s page.

Each time Syrian opposition accounts or posts get banned, The Syrian Electronic Army is mentioned as a possible suspect. From as early as 2011, they surfaced as a guard of the Syrian regime’s narrative on the internet. They are a collective of pro-Assad hackers and online activists who use tactics of attacking websites, Facebook pages and accounts, phishing campaigns to steal accounts, or flooding the social media with pro-regime messages. Their Facebook page does not exist anymore, and their efforts are hidden from the public platforms, many believe they were behind the latest reporting on al-Sarout posts. However, no matter who did the reporting on those posts, the question is how Facebook reacts.

In many ways, these censorships resonate in the Palestinian context. Palestinians have also been the victims of Facebook censorship, though in the Palestinian case the “Israeli electronic army” works in the light.

In September 2016, Facebook met with Israeli officials to discuss cooperation in dealing with “incitement” on Facebook. Few months after that meeting, Israeli Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked reported that Facebook responded positively to 95 per cent of the requests made by Israel to remove Palestinian content.

“Sada Social”, a Palestinian initiative that documents social media platforms violations against Palestinian freedom of speech reported 200 cases of shutting down accounts, deleting pages and banning posts on Facebook throughout 2017. And 370 cases throughout 2018.

According to Nadim Nashif the director to 7amleh, the Arab Center For the Advancement of Social Media, “There is a cooperation between a coordinated effort of Israeli governmental bodies including the Cyber Security Unit ran by the state attorney's office and semi-governmental bodies such as organized students’ groups and mobile apps to report on Palestinian content and on the other hand Facebook’s responsiveness, that stands behind this massive censoring of Palestinian voices”.

Whether in the Palestinian case or the Syrian, it’s clear to Nashif that “This is a war over content, the power dynamics that exist in reality are reflected in this war. The party that is more organized and has the human and financial resources wins.”

Indeed, the way Facebook functions when it comes to moderating content sets the ground for these power dynamics to unfold in the cyberspace as well.

Facebook evaluates content according to its “Community Standards” which, were made public last year, after an ongoing pressure and criticism against the ambiguity of its decision making when it comes to deleting content and policing speech. These 27-page document on standards guides the work of Facebook human moderating teams. These teams work in what is known as the “deletion centers”, which are usually employed by subcontractors of Facebook and are located in different parts of the world to respond to different time zones, languages and regions. Employees in these centers are responsible for moderating the content of Facebook posts that are reported by other users, and decide whether they should be deleted or not.

A team of Facebook’s experts develops the Community Standards, but their work is influenced, of course, by the context in the countries Facebook is functioning in.

It is no secret that Facebook complies with governments’ restrictions because its existence in many countries is under the scrutiny of the authorities there and dependant on their permission. This means that governments have potentially, though not all of them use that potential, a say through political and legal means in formulating Facebook Community Standards. They also have the power to censor certain accounts, posts or pages through submitting direct requests to Facebook, as is evident in the Israeli case.

Syria Untold talked to a former employee in one of Facebook’s “deletion centers” in Berlin, who requested to remain anonymous.

al-Sarrout was on Facebook terrorists list and this is why all posts “praising him” were deleted.

He said that al-Sarrout was on Facebook terrorists list and this is why all posts “praising him” were deleted. The moderator used to be one of the hundreds of employees who work for sub-contractors of Facebook and responsible for examining content and deleting it when it violates Facebook’s Community Standards. In Germany, there are two such centers, one in Berlin, opened in 2015 and operated by Arvato, a division of Bertelsmann and specializes in customer support and one in Essen opened in 2018 and operated by Competence Call Center, a European company that runs service centers around Europe. Both employ over 1000 employees. Other such centers function in different parts of the world and employ over 15,000 employees, according to Facebook.

Each employee, when accepted to the job, undergoes an intensive training course, after which he/she is “supposed to know the guidelines by heart”, said the Facebook moderator. “What Facebook publishes as “Community Standards” on its platform are way smaller than the guidelines we work with. The public ones are very general, we have detailed documents with names and lists of organizations and figures that any content related to them should be banned.”

He is referring to the 1400-pages internal booklet, which was leaked to the New York Times in 2018. The paper highlighted that these files reveal “numerous gaps, biases and outright errors”, and how Facebook has the power to “shut down one side of a national debate” through its content moderation.

Employees in deletion centers rely on these guidelines when deciding over content. They will delete any post supporting a group or figure on that list, if spotted.

According to the former moderator in Facebook deletion center, “we examine content that gets reported. So in order for us to decide on a post whether to be deleted or not, it has to be first reported, whether one time or 1000 times, it doesn’t really matter. Any reported post would come to us for judgement.”

“We can see who reported this content, but we do not check who is the reporter, if he is a troll, someone who is part of an electronic army, an account that is managed by governments or so on. We don’t do that, we just look at the content that has been reported”, he tested.

The community rules can change from one night to another. “I remember that one day, we arrived at the center and we received the announcement from our supervisors that Khairat el-Shater of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt was now on the terrorists list, so from that moment on, any posts that praise him, should be removed.”

If anything, this shows how politicized the process of forming the Community Standards is, even if the changes seemed arbitrary at times. But also, to what extent these moderators understand the nuances and contexts of each country or situation is called into question. They have little time to decide on a post and they rely on their training and the booklet as a reference.

In the case of al-Sarout, activists did “request review” of the deleted content, including Namer. However, It is hard to believe that this action has pushed Facebook to reconsider. According to the former moderator “In 99% of the cases where users request reviews, the decision does not change. Only when there is a higher pressure on Facebook, it would reconsider and change decision.”

These activists further mobilized, and organized a campaign calling on Facebook to lift the ban, reposting content with al-Sarout hashtag and signing a petition. We could not confirm what exactly happened inside Facebook concerning the ban against al-Sarout, but it’s clear that the pressure was successful.

“Facebook’s admission of al-Sarout exoneration of radicalism was the result of efforts by faithful Syrians and Arabs in response to massive and systematic reporting that aims to block Syrians commemorating their popular hero, al-Sarout. This admission was reflected by lifting the ban on posts related to al-Sarout and publishing back what was removed.” actor Feras Helou wrote on his Facebook account.

I saw this as a battle over who writes the history. The revolution is over and now the battle is over its narrative.

“I saw this as a battle over who writes the history, it’s a battle similar to our battles on the ground. The revolution is over and now the battle is over its narrative. For the regime and its Russian allies identifying al-Sarrout as a terrorist serves their narrative, but for us, he represents a man who believed in freedom and in revolution and sacrificed his life for it.”, said Namer.

Though this incident could be marked as a victory for the opposition, it still highlights, on the one hand, the problematic power Facebook has in policing the freedom of speech, and on the other, how these social media platforms has turned into a battlefield of clashing narratives. Those who have more power, would usually end up having the upper hand. And when it comes to Facebook, the upper hand doesn’t seem to be the ally of the oppressed.