Place: Ravensbruck/former Nazi concentration camp for women and young girls, and a current memorial site and a visitor centre with a hostel.

Time: September 2018

The administration suggested that my colleagues and I hold the annual workshop at a hostel in Ravensbruck area in north Brandenburg province, which was previously a women’s concentration camp in Nazi Germany. The camp was transformed to a memorial site and a visitor centre which included a hostel, and this transformation was based on the request of the survivors as we were told. They wanted it to stand as a lasting witness to the suffering it once saw and to the pain of the prisoners who were locked up between the walls of its cells, and to remind the future generations of the crimes of racism, and of hatred and rancour. I was overwhelmed with preparing for the annual workshop, and I focused on that to the extent that I did not seriously think about the place where I would be staying in Ravensbruck.

I was a little worried at the beginning, but perhaps I did not take it seriously enough. Besides, I had very little information about the place.

I had always believed that each place has its own memory, and I often thought individuals relate to this memory, each in their own way. But, I did not know that the memory of a place that is strange to me could resonate with me so strongly and would make separating myself from it almost impossible. Being introduced to the memory of a strange place is often an ephemeral experience. However, when the details of such a memory touch on a person’s own memory, the latter becomes part of the former or is reborn anew.

Enigmatic beauty

I left Berlin, the city in which I now live and work, and I headed to Ravensbruck with my colleagues. It was noon, and despite my prior knowledge of our destination, I could not imagine what was waiting for me or understand what it meant to stay in a Nazi camp for three days. So, I was full of anticipation and decided to wait and ignore the confusing and worrying questions that were multiplying in my mind. After all, I would not be there alone, but with my colleagues. This thought gave me some comfort, at least for a short while.

As soon as we arrived at our destination, the natural beauty around us captivated me and distracted me from the questions and concerns that were eating me up. Near the entrance of the camp and before going through its gate, I was charmed by a spectacular view; an incredibly green interlocked forest trees with varying lengths. To add to their beauty and elegance, chirping birds could be heard all around, and a bit further to the right, one could see the Schwedtsee Lake, the camp is located on its north-eastern bank.

At that moment, the shimmering sun on the lake surface drew me in, the sun is shy in this part of the world usually. The lake seemed blissful, calm, comfort-inducing and made me feel optimistic. The overwhelming beauty surrounding the place gave it an entrancing elegance and charm that would blow everyone’s mind away.

The time had finally come — we had to enter the camp and go through its main gate! I walked in slowly, and I was alert as I tried to get a feeling of the place. However, I was still unable to shake away the mesmerizing feeling I had when I saw the beauty of the surrounding nature. I looked around me to examine the setting and terrain. I gazed at the monotonously lined buildings left and right, and the image of the beauty of nature started slipping away gradually from my mind.

The buildings where those in charge of the camp lived stood on a hill, the residences of guards, prison supervisors and Nazi officers were located there. They were overlooking the rest of the prison that consisted of buildings and prison’s yards, where a large number of female prisoners used to be crammed in.

Moving my eyes from one corner to the other, I was utterly shocked. Flashes from personal and bitter memories came rushing back my mind, as if to wake me up completely from the sedating beauty I saw on the entrance of the camp, or to punish me for allowing myself to be enchanted by it. It was as though the wall surrounding these ugly, crammed buildings here and there aimed to isolate the memory of this place and keep it undiluted by the all-engulfing beauty around it.

The words “how similar it is to the camp!” escaped my lips. I was talking about the camp where I lived for the longest year of my life, 12 years ago, when I first came to Germany with my family. But, this place was so daunting that it snatched me away from my memories and took me to its own memory.

The colluding beauty

I tried to grasp the “meaning” of this place, I was trying also to escape my own memories haunting me, and anyway they were starting to fade under the imposing character of the camp. I spent the first day inquiring about its history and reading the available information online. Gradually, it all became clear, and the gaps started getting filled, like rearranging a puzzle or zooming in on an image.

My primary research added some clarity to the surrounding setting, and I delved into, or perhaps drowned in, the memory of the place.

The camp was constructed between 1938 and 1939, based on orders from the Schutzstaffel (SS) leader Heinrich Himmler. It was, in fact, the detainees of Sachsenhausen concentration camp who built this new Nazi ward, which was the unit’s biggest detention centre.

The detainees were forced to work as slaves to build this women-only detention centre, which, ironically, would hold their daughters, sisters, mothers or lovers captive.

I wondered, without daring to imagine, what images must have haunted that detainee, who knew what fate was waiting for him in these concentration camps, while building another detention centre whose prisoners would face the same fate as his.

In 1939, the camp was completed and became the largest women’s camp on German territory, accommodating 132,000 girls and women by 1945[1]. Tens of thousands were killed in gas chambers, starved, died of illness or underwent fatal medical experiments. In the spring of 1945, after World War II ended and the Soviet Red Army approached, the Schutzstaffel exterminated the largest number possible of male and female detainees in the Nazi death camps[2] . Those detainees were found “guilty” of surviving, which made them witnesses to the Nazi atrocities against them. By the time the liberation was completed, the Nazis had killed tens of thousands because they feared their collective memory.

The blatant contradiction between the beauty of the place on the outside and its heinousness on the inside was mirrored by those who worked in it as guards and wardens. On the outside, they looked normal, and even beautiful human beings, just like their victims. But inside, they were sadist monsters in their practices, and they took pleasure in torturing those whom they deemed racially inferior to them. In the cells of Ravensbruck camps, some guards, like Irma Grese (1923-1945), were nicknamed “the beautiful beast”

What memory do executioners fear?

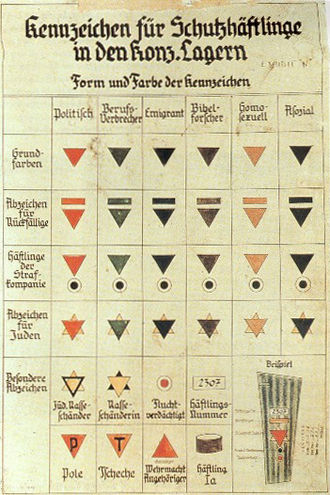

Women from 40 different ethnicities and nationalities faced a torturous, oppressive and bitter fate at the hands of the Nazis. When Nazis arrested new women and took them away to Ravensbruck concentration camp, they gave each a number and a code or initial to classify them. The initial was put inside a coloured triangle and sewn on their clothes, and it represented their “category” or the “crime” that led to their arrest. According to Nazi colour coding, green was the colour of “professional criminals” in custodial arrest. Red was the colour of Soviet political resistance members and prisoners of war. Purple was attributed to Jehovah’s Witnesses, while black was reserved for women categorized as “asocial” like the mentally ill, the disabled, the homeless, the addicts and other marginalized groups who were socially rejected. Brown was for gypsies, blue for migrants and pink for lesbians. Jewish women were made to wear the Star of David to set them apart from the rest.

Shocked, I walked alone between these temples of torture. I was lost in my own mind, the silence of this place is deafening now, but I kept imagining the howling screams of the inmates who were once tortured here. I paused next to a huge hangar where the prisoners spent long hours of hard labour daily, sewing or doing delicate handwork. I stared into the intense void between the walls and asked myself again, “Will these walls stay silent forever, after having witnessed later the torture suffered by the very people who were forced to built them? Was some of that anguish mixed with their cement, and will the memory of it linger forever in these walls ?”

Between these walls, I was looking for any echo from the past. I hoped it will alleviate my sense of alienation, and help me tolerate all this senseless and impossible cruelty.

Sleeping in the criminals’ beds!

The more I walked, and the darker it got, the lonelier I felt. The presence of my colleagues was no longer a source of consolation. I was completely alone in my head as I stood there, facing an avalanche of memories, eating me up and devouring my personal memory. Night fell, and the trip supervisors told me where I would be staying! I was to sleep in a guard’s room! How could I? How could I sleep in a criminal’s bed, with all those voices screaming in my head?

I entered the room, as though it was the zero hour of war. There I stood with four single bunk beds and a window overlooking the fence of the camp.

I lay down on one of the beds, and I stared at the bottom part of the bed above me. Did the guard who slept in this bed inspect the steel bottom of the upper bed until she dozed off, just like I was doing now? Which side did she sleep on? Did she dream? Did she think of her victims and their pain? Did she have nightmares? Did she have a guilty conscience?

I shook my head in an attempt to shake off all those questions, and I resented my preoccupation with the guard. I tried to put my troubled head where she once slept, but I failed to sleep, and soon I had to rush to the lonely window, like myself, in this nightmarish room. And I felt as if I became one with this window, the fence was the only thing we both could look out at, and the fence was closing in on me, as was this room. The window was no longer an opening from which one could see the fence, as that fence was besieging both of us now.

The camp... what lies beyond the fence ?

They called that hole in time and space a “camp”, but Landesaufnahmebehörde Niedersachse felt more like a detention centre. That camp was the first to “embrace” my small family and me when we arrived in Germany in 2006, the country that proudly calls itself a host country for refugees. But the embrace was too tight, and its grip was inescapable, just like the camp’s high metal fence. It surrounded us, as if it is a mother’s eyes that never stop watching over her baby.

With the naivety of a 15-year-old, I asked a Syrian lady who had been stuck in the camp for a year and a half why we were “besieged” within this fence and put under intense supervision. I can’t recall how long I have been there, nor where we sat when this conversation took place. In a camp, time becomes fluid, and all the places feel the same. Time is reduced to waiting, and the memory of an alien place is taking over you.

The woman answered with conviction, “To protect us, my dear child. There are many racist Germans in the area around here.” We were not allowed entry back to the camp after a certain hour in the evening, and we often avoided leaving the camp in the first place to save ourselves the humiliating treatment we received from the guards when we left or returned.

With naiveté and delusion stemming from a desire to humanize this place, I thought to myself, “wow, how caring and attentive to our safety and security our host country is!”

We were a small Syrian family that escaped the “embrace” of our home country; an embrace that imprisoned my father and his friends who opposed the oppression and tyranny of Assad’s regime. In our homeland, we were indoctrinated at an early age that Syria has delivered a one and only note-worthy son. When you are young, how you are delivered to the world from your mother’s womb sounds like a very vague procedure. Yet, before we were old enough to understand it, we were told that Syria, our motherland, “gave birth to a child and named him Hafez al-Assad.”

But our motherland “embrace” swallowed my father and his friends, and threw them into the shadows of its deepest, darkest, loneliest, most painful, isolated and agonizing abyss. Political dissidents in our country were imprisoned in underground dungeons. They were kept deep under the same ground on which thousands walked every day; shoppers, students, and daydreamers. Many were unaware of what went on under the very ground they were walking on, some knew and chosen to remain silent for they were helpless and unable to change it.

Each time I finished reading one of my father’s letters that were smuggled from the prison, I felt I was agonized by more curiosity and disappointment.

My father, Marwan Othman, refused to mention any details or description of the place which took him away from me for years. He was a writer and a dissident, and the Syrian regime imprisoned him repeatedly in the 1980s and 1990s. On December 10th, 2002 he participated in a demonstration organized in front of the Syrian parliament on the International Human Rights Day, and he was arrested. The Supreme State Security Court sentenced him to 3 years in prison, after his release we fled to exile.

But, once, from within the confines of his first exile, while still in his own country, he smuggled out of his prison a poem he wrote. His friend printed it out and handed it to me. It was his gift to congratulate me on my succeeding in the ninth grade, and he wrote describing his joy:

“This land is beautiful

but its beauty fades,

once you open your magnificent eyes to this great prison of ours;

once an amazing nation in the past.

Tired of its absence, we lived on

in a facsimile of life;

we ignored our homeland;

real, yet seemingly fictitious;

like a story that only existed between the pages of books.

Our glorious homeland;

the smells of the fresh earth,

moments before soldiers’ boots trod on it.

And there I see you,

sketching the roads that lead to our house,

its geography, now surrounded by misery and spies.

Yet, I embrace this homeland,

and I wait and wait

for the dream your hands are bearing,

and for the lilacs transpiring in your vision.

And the dream is tantalizing,

but your absence becomes overwhelmingly present.

It scatters what strength I have left,

with my tears and yearning, I call for you.”

My father and his friends, along with the generation of the Syrian revolution that erupted later in 2011, were singing out of tune in “Assad’s Syria”. Yet, their discordance was the only pleasing melody amid the prevalent monotonous rhythm of our public life that was politically, socially and economically controlled on a daily basis. The timeframe of this rhythm was defined by the life of the maestro or the “immortal leader”, and its spatial frame was controlled by the security branches, and ideological schools and public institutions that were deeply corrupt. The lyrics to this rhythm were derived of the literature from the Baath party and its “revolution.”

The first victims of the Baath Party revolution that took place in 1963 were the weak and the oppressed that this “revolution” claimed it took place to defend them and speak on their behalf. However, the Baath only used these people to seize control in the country, and later abuse its wealth and its citizens, until it left the weak and the oppressed it claimed to defend completely crushed and alienated.

Our story was not different. We were refugees escaping a possible violent death in our motherland, after our country tormented and rejected us. Now in exile, we face a slow and “merciful” demise, while all we do is wait for the “post.”

The post was to bring us a letter, and though we didn’t understand much German, but understanding these letters and the legality of our situation was the only common interest we shared with the others as refugees living in the same camp. For we all came from different countries and spoke different languages.

Waiting for the post was like waiting for Godot. And all our hopes in life were reliant on receiving a letter in a language that is foreign to us, but that letter is the only salvation that would end our waiting and save us from our memories. That letter was our only chance to start building a life for ourselves, and to escape the “limbo” our present has become.

And like my father and his friends in our country, we as refugees now, have become a discrepant discordance that ruins the beauty and harmony of the place beyond the fence of the camp, a beauty that was reserved for the Germans who live outside. Their lives were normal and natural, and that in itself was a daily reminder of our past lives, and of our own natural and normal that we once lived before this transitional phase, which has lasted so long already that it became our new norm. Our dreams and ambitions became restrained and limited to the confines of the metal fence. The fence was shackling our bodies and imagination, while we looked out to the outside world through its holes.

The first time I left the camp, I felt that crossing the fence was an adventure. But this adventure was sufficient to dispel any illusions I once had of “deliverance”. I walked away from the fence and headed through the woods towards the city and its bustling life. But little by little I was feeling more lonely and isolated, and I was realizing that the Syrian lady was clueless and did not understand that the fence was not protecting us from evil Nazis outside, but it was protecting the outside from us.

That fence was there to help spare their eyes from our sight, and to protect them from our strangeness and the multitude of our origins and tragedies. It was meant to shield them from realizing our “parasitical” presence, for we were merely greedy insiders invading their world. I realized we were stuck in a place that spitted us out, just like our countries did. The camp was located on the periphery of Braunschweig city, in its loneliest, most silent, isolated part and it was largely disconnected from life, services and people.

In this new place, the deserted and eerie forest was our first neighbor, and a letter in the post was the first “dialogue” we engaged in. We were largely left to our internal monologue, we were mere numbers. Our lives were put on hold, and we were stripped of our identity.

Ironically, It was the forest that took my breath away with its beauty when I first entered Germany, before becoming a refugee here. It was a forest again that captivated me with its lush verdancy and charm before I stepped into Ravensbruck concentration camp.

Overlapping spaces and eras

My friend woke me up at daybreak. “Did you really fall asleep here?” he asked.

On that day, and after a bitter struggle with my memory and with details I had blocked out 12 years ago, I tried to conceal the dark circles under my eyes and gather my strength to return to my colleagues and complete the deliberations, readings and tasks we had come for. After we finished our work, a lady who was an expert in the history of the camp took us on a tour to tell us what had happened here and to answer any questions we might have. That was my second tour exploring the past of this camp. There was one place that I was unable to reach in my first tour. It was the crematorium, and the lady took us to see it. It was there that the bodies of the victims, enfeebled by pain, torture and dying, were transformed into light, formless ashes.

I asked, “Where did all the burnt bodies go?”

She answered, “They were thrown in front of the door of the crematorium, here, where a memorial stands.”

The tour guide added, “Most ashes were thrown in the lake there, where we I will take you now.”

“The lake!” I let out a shy scream.

It was the same lake I was infatuated with its vivid blue colour and the shimmering sun reflecting on its surface. I arrived there and inspected it again, but this time I was angry. I wondered, “How could this beast, which swallowed the souls and ashes of the bodies of thousands of innocent people, mesmerize me? What deceitful, soul-robbing beauty this beast has!”

We then heard the church bells. I looked around, searching for the source of the sound. The guide pointed to the other side of the lake, where a small town was located.

I had one question at that moment, “didn’t they do anything? How could they just watch the pain and agony on the other side of their lovely lake? The distance is so little they must have heard the agonized screams and smelled the burning bodies!”

The tour guide answered that most of the townspeople who lived there in the days of the camp denied knowing about what was happening inside. They claimed that the wind blew in the opposite direction and made it impossible for them to smell the burning flesh.

This denial is the same as the one that made many of my compatriots choose to turn a blind eye to the killing, arrest, forced disappearance and alienation of their fellow citizens. They refused to admit the darkness of oppression we lived under, they choose to acknowledge one “truth”; that “Syria gave birth to a child and named him Hafez al-Assad.”

There I was, remembering the massacres of Assad’s regime against our people. At that moment, I was struggling to find some hope in the midst of my overwhelming frustration and anger. I looked at the guide and asked, “What happened to the guards and officers of Ravensbruck? Were they punished? Were they held accountable?”

She was concluding the tour, and her answer also finished any resistance left in me, and I gave in to the overwhelming frustration. She said, “only a few of those in charge of the camp admitted their responsibility when they faced trial. Most of them answered, ‘what could we have done!?’”

However, they could have done something, and the documents that prove that some former guards resigned is a testament that they could have done something! Resigning was a choice!

How could they have escaped punishment? What use was it to commemorate this history, as long as its atrocities are allowed to repeat themselves? One thing only changed; the identity of the victims! What good did remembering do in a world which still can be descriped as Hannah Arendt wrote 70 years ago, “ we actually live in a world in which human beings as such have ceased to exist for quite a while, since society has discovered discrimination as the great social weapon by which one may kill men without any bloodshed; since passports or birth certificates, and sometimes even income tax receipts, are no longer formal papers but matters of social distinction.“

Will a day come when criminals in my home country also escape punishment? Will the day come when their temples of sadism; their jails and slaughterhouses, are closed and turned into memorials for future generations to remember? Is it possible that I would one day be sleeping in the cell that stole years of my father’s life in the past? Will the fact that the Syrian war is the most documented war ever in the modern history, with photographic and video evidence, change the course of history, and prevent the atrocities repeating themselves?

Were the Ravensbruck guards and executioners’ fear of their victims’ memory justified? I pose this question as I think of all the abuse, displacement, massacres and identity-based cleansing we are witnessing now and have witnessed in many recent wars. I ask this question as I contemplate the world’s indifference to the pain and suffering these wars are causing in many countries, and the sudden rise of racist parties and groups that are reproducing hate and a culture of division .

Were their fears justified, when a prominent leader of the Alternative for Germany party, Björn Höcke, called for “a 180 degree turnaround in our policy of memory" currently adopted in Germany? Today, German students study in history books, just like I studied in secondary school, about Nazi racism and its crimes and the fate of its victims. They learn to remember the criminal past. But Hocke called for revising the way the past is taught, and teaching instead about its positive and proud parts and instilling in the students a love for the fatherland. Hocke’s arguments are consistent with the right-wing thoughts and narrative that are increasingly gaining traction in the current political and electoral scene in Germany.

The memory of the victims is indeed a weapon, one that should be raised in the face of criminals throughout history. But, how effective this weapon is when history is repeating itself, yet this time the perpetrators are being exculpated. How effective this memory in defying a tide that is rising in many countries across the world, and it is reminiscent of the situation and the context that preceded the Nazi takeover of the rule in Germany in 1930s?

In our modern times, the survival of the victims came to mean turning them into refugees. And becoming a refugee became synonymous with rebirth. Being identified as a refugee, or “fluchtling” in German, doesn’t allow you the luxury of being perceived as a person with a memory of his own, and an identity and previous personal experiences. The residence card you are given as an identification reduces your humanity to be identified only as a refugee.

And we “the refugees” are always in the headlines of newspapers in our host countries. We are a material for endless debate in the press and our presence is a controversial issue that is contested and widely debated in electoral campaigns. Several walls, not just one, have been built to protect the borders of many countries across the world agianst us, and the people have become divided between supporting and opposing the “burden” of our presence.

Still, we as a “burden” became lab rats for integration experiments. And to prove that we are integrating well into our new societies, we are asked to assimilate to a point where we cease to be ourselves, and where we become entrapped in a perpetual image of being a burden to society. We are always subject to questioning, but we are not allowed to raise questions ourselves. We are constantly expected to prove and explain ourselves, and to answer for any problems that arise from the refugee community. We are expected to try and become “white”, to adopt our host society ways of living, and to be grateful, extremely grateful.

The sense of entrapment I felt as a 15-year-old refugee when I was besieged between the walls of the camp remained deeply buried in my memory. But the memory of the victims of this Nazi concentration camp and thinking of more recent wars and waves of displacement brought that sense of entrapment back, and I feel it as strong as I did when I was fifteen.

[1] Source: Silke Schäfer: Zum Selbstverständnis von Frauen im Konzentrationslager. Das Lager Ravensbrück. Berlin 2002, S.25-26.

[2] Source: Stefan Hördler: Die Schlussphase des Konzentrationslagers Ravensbrück. Personalpolitik und Vernichtung. In: Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft. 56. Jg., Nr. 3, 2008, S. 247