It was sometime in early autumn when several dozen men gathered outside in a Daraa street.

In a sign of protest that is rare across the vast majority of government-held Syria, they chanted against the government before packing up and heading back home.

“I felt like I was still able to raise my voice,” says Nour,* a resident of Daraa city who attended that autumn demonstration. It’s the most recent protest visited by the activist, who is still wary of facing security repercussions. Now unemployed after years working as a medical aide in nearby displacement camps and field hospitals with the Syria Civil Defense, the group of first responders known as the White Helmets, Nour doesn’t venture too far, fearing arrest at roadside pro-government checkpoints not far outside the city.

But inside Daraa al-Balad—Nour’s neighborhood, where the government still enjoys only nominal control—a sense of enduring protest still cuts through the fear, local residents say.

They blame more than a year of unmet promises from the government, with many basic public services such as water and electricity still lagging and security forces continuing arrests and disappearances of hundreds of people with suspected ties to the opposition. More than 650 people, the majority of them civilians, have been arrested since the Syrian government and its allies retook the southwest from the opposition in mid-2018, according to a count by research group Etana. A recent freefall in Syria’s currency has only compounded these frustrations, residents say.

Meanwhile, a string of assassinations blamed on government forces, targeting former opposition leaders, has riled Daraa province for months.

“What I saw was that people will go back and revolt all over again because they are losing hope,” Nour recalls of that autumn protest.

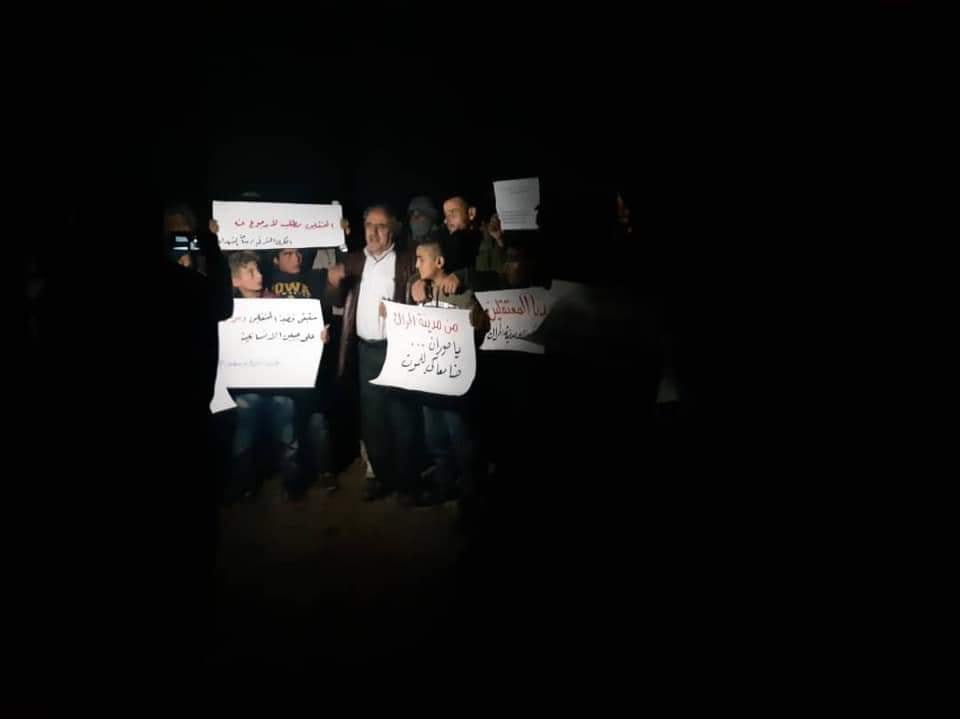

There have been other demonstrations since then, with videos shared online in succession by activists. In one from November, at least a dozen men bundled in winter coats ride their motorcycles through a Daraa street by night, calling out familiar protest chants demanding the release of detainees. ِAnother, posted earlier this week by local media activists, shows men gathered by night in an eastern Daraa town, their faces covered by scarves and posters scrawled with slogans.

Deadly pattern of ‘reconciliation’

Since 2016, the Syrian government and its allied forces have retaken city after city from rebels in a usually deadly pattern: bomb, starve, negotiate surrender then remove thousands of remaining residents and fighters by bus to Idlib and the opposition-held northwest. Once vibrant working-class districts of Homs, Aleppo and the Damascus suburbs now sit devastated—largely as they were left after years of siege came to an end with evacuations.

Daraa was different. Once home to revolution’s first rumblings in 2011, the southwestern province bordering Jordan later came under the control of an array of opposition forces whose control stretched from the Roman city of Busra a-Sham in the province’s easternmost reaches, to neighboring Quneitra province, a sliver of countryside in the foothills of the Golan Heights. The southwest came to be regarded as one as the Syrian uprising’s key constituencies.

But in June 2018, pro-government forces launched a lightning military campaign to retake the entirety of opposition-held southern Syria, all the way to the Jordanian border. Daraa had finally fallen back into the government’s hands—although much of the takeover was due to negotiations and surrender deals with local rebel leaders. In return, Daraa would receive public services, the release of detainees and the creation of the so-called Fifth Corps, a Russian-backed initiative meant to reintegrate ex-rebels into an adjunct division of the Syrian army. Or at least that was what was promised by government negotiators.

The result was a mismatched series of agreements. In eastern Daraa’s countryside, local rebel commanders signed on to a set of surrender and handover deals, meaning that government authority would largely return to some degree of normalcy.

However, in Daraa city’s former opposition-held neighborhoods and other towns dotted around the western countryside, government forces would only hold nominal control, allowing former rebels to keep hold of light weapons and some form of autonomy.

For neighborhoods of the provincial capital such as Daraa al-Balad, where Nour lives, that meant little to no government presence at all, making the area relatively safe for protestors gathering in the streets.

But elsewhere, pro-government forces including Hezbollah and Iranian-backed factions also maintain a presence—particularly in Daraa’s western reaches.

Residents blame them for a wave of assassinations targeting local figureheads, including former rebels.

The funeral last month of one prominent leader, former Free Syrian Army commander Waseem al-Rawashdeh, ended in dozens of protestors marching through the western Daraa town of Tafas against his killing—allegedly at the hands of gunmen linked to Damascus.

Most recently, unknown gunmen reportedly shot and killed the local mayor of a-Shajarah, a western town previously under the control of an Islamic State affiliate. Local monitoring group Houran Free Media appeared to blame the assassination on pro-Hezbollah fighters present in the south.

In response to the ongoing killings, groups of men have attacked government-affiliated checkpoints and buildings across the southern province.

Tensions have at times erupted into armed clashes between local gunmen and pro-government forces, with Damascus reportedly sending reinforcements to the reconciled town of Sanamein in September, in a bid to quell the violence.

Increased violence ahead

Despite the promises of government negotiators during the takeover last year, the western countryside remains largely neglected, taken over by force rather than through the surrender agreements that saw towns and villages elsewhere taken haphazardly back into Damascus’ fold. Hospitals, schools and other public services are still in disrepair, with one resident of a western Daraa town describing medical care in his area simply as “nonexistent.” Water and electricity cuts are often.

The discontent could fuel more protests in the future.

One resident of Tareeq a-Sadd, another former opposition-held neighborhood of the city, described himself as “close friends” with members of a local committee set up as intermediary between residents and the government. Nevertheless, he complained of a “lack of effectiveness” by the committee to secure steady services for residents or mediate with government officials on their behalf.

“The protests will of course continue if living conditions keep deteriorating, if the government’s infractions against people keep happening. People will keep demonstrating,” he said.

“My own brother has been detained for six years; we don’t even know if he’s alive or dead. I have to protest.”

Another resident named a fellow activist and friend, from western Daraa, who had recently been detained by government security personnel.

A man in Tafas, in the countryside west of Daraa city, said his greatest concern was the “security chaos.”

“There are assassinations happening all the time,” he told Syria Untold.

With return of state control itself is a matter of dispute, and little attention to improving Syria’s still decimated southwest, the instability could grow, according to one Syrian researcher who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons.

“Do we mean the state institutions are back to resume service provision? Or do we mean the return of ‘state sovereignty’ in that the state has the exclusive control of people and property?”

“It’s a very tricky statement.”

“If the Syrian regime doesn’t take serious measures and respond to the civilian demands in Daraa, we are more likely to witness chaos and an increase in political violence,” the researcher added.

In Daraa al-Balad, that uncertainty has left Nour afraid to leave the city. Inside the formerly opposition-held neighborhood, the activist is safe—government personnel have no presence there.

But outside, there are checkpoints manned by Damascus’ security forces.

And last year, they sent a note to Nour, requesting that the activist visit their headquarters for an “appointment.”

A note typed at the bottom of the paper request warned “legal procedures” would take place if the appointment wasn’t met.

Nour never went.

“Of course I didn’t go. There were no guarantees I wouldn’t be detained right there.”

*All sources quoted in this report asked that their real names and identities be withheld for security reasons.