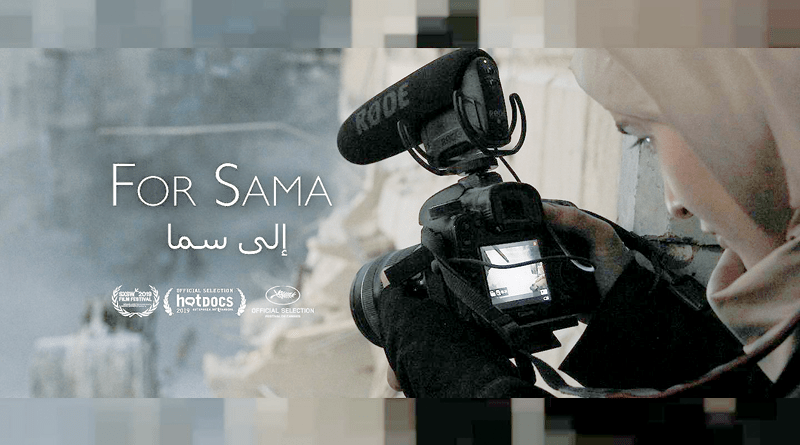

The beginning of 2020 marked a milestone for Syrian filmmaking. Two Syrian films, “For Sama” by Waad al-Kateab and Edward Watts (2019) and “The Cave” by Feras Fayyad (2019) were nominated for the Oscars in the Best Documentary category. (This was the second time for Fayyad, whose previous film, “Last Men in Aleppo,” received a nomination back in 2018.) Nominations in such a prestigious, mainstream context helped these works leave the European “elite” festival circle—"For Sama” premiered at Cannes in 2019—for a more appealing and rewarding path toward audience success at the box office and on global media platforms such as Amazon Prime and Netflix.

For all those working in the field of promoting and curating Syrian arts and culture, this should be great news. Syria goes to Hollywood, finally hitting the mainstream. We should be celebrating, shouldn’t we?

I first watched “For Sama” in a movie theatre with hundreds of seats, all taken, during the Med Film Festival 2019 in Rome. It was a success: a full-house premiere followed by long, enthusiastic applause. It is difficult not to be emotionally moved by a film that sheds light on all sorts of human violations against civilians in Syria, and it does so through a first-person account, perhaps the most powerful one: that of a mother telling the story of her ravaged country to her newborn in the form of a love letter. The key of the success of “For Sama” is precisely this very personal and yet, at the same time, universal story: a mother fighting for her children’s right to live in a free country.

Al-Kateab's emotional pledge is to explain her soon-to-be daughter why her parents decided to stay in Syria and fight to free the country from the authoritarian rule of a leader who has destroyed entire cities based on the excuse that he is exterminating dangerous “terrorists.”

In one of these devastated areas—Eastern Aleppo, to be precise—al-Kateab gives birth to Sama, at the same time giving birth to images that are so powerful that the trapped citizens’ lust for life seems to emanate directly from the pixels and into the audience’s face.

One single screening of "For Sama” touches the hearts and souls of global audiences much more effectively than a thousand street demonstrations, op-eds, books, TV interviews, public gatherings and workshops that seem not to have worked so far to sensitize international public opinion to the plight of Syria's revolutionaries. Moreover, al-Kateab and her husband Hamza—the brave young doctor who also stars in the film—have staunchly held up the sign, “Stop bombing hospitals,” throughout the entire international tour of the film, on red carpets from Cannes to the Academy Awards, to spread the word about their ongoing fight for Syria, even when they are out of the country and enjoying international success. All this would suggest that “For Sama” is the perfect example of an arthouse and activist film that also manages to reach the attention of international audiences and sell at the box office.

Al-Kateab’s filming style—“handheld,” shaky, low-res—takes the viewer underground with her. We are transported to Eastern Aleppo. We are there: under siege with her, fighting for our lives, terrified that life will be taken away by a coming aerial attack.

Why, then, in spite of this, does this film leave me unconvinced and even a bit cold—apart from the (expected) effect resulting from the words of a woman voicing her maternal love in an extreme situation of life and death?

My feeling of uneasiness is twofold. Firstly, I have an aesthetic reservation towards “For Sama" that ends up becoming an ethical one, too.

Al-Kateab’s filming style—“handheld,” shaky, low-res—takes the viewer underground with her. We are transported to Eastern Aleppo. We are there: under siege with her, fighting for our lives, terrified that life will be taken away by a coming aerial attack. We are stuck in the tunnels of the makeshift hospital, with no escape, our fear and claustrophobia rising.

Then, suddenly, we are taken to the surface, as if to be granted some precious breath. The camera exits the underground tunnels, goes outdoors, rises up and reaches over our heads. All of a sudden, we are gifted with the spectacular, amazingly well shot, high resolution drone-view of the area. Lost in this magnificent aerial view, we tend to forget the makeshift hospital, the tunnels, the claustrophobic human lives consumed underneath. We get lost in the hyper-aestheticized view of the destroyed city. “War is beautiful,” as American author David Shields provocatively once wrote. Isn’t it?

This drone view adds the spectacular to the film and makes it look like a proper mainstream documentary made for the consumption of Netflix and other similarly global palates. While inserting these dramatic drone shots makes “For Sama” closer to the aesthetic language of contemporary mainstream documentaries—and therefore more marketable and sellable—it also compromises the film’s narrative credibility as a result. The technique of the hand-held camera and first-person point of view had built a trust in al-Kateab’s story, in the “being-there” of the recording device and its narrator, in us “being there” with them in those claustrophobic tunnels. But the glossy aerial shots taken by high-res cameras carried by drones break that trust. ("Whose drones are these?” and “Who paid for them?” are both legitimate questions that arise once the trust is broken.)

This surrender to mainstream aesthetics sacrifices the ethics of the film and undermines its “local” credibility. Native narratives are, once again, made into subaltern narratives. They are made to surrender to the imperatives of mainstream (western) taste. They have to assimilate, if they want to be sold and consumed, if they want to make an “impact” globally.

This is a political statement that Syrian cinema is forced to both adopt and adapt to if it wants to succeed. Syrian films should accept such things as drone aesthetics in order to beat market competition, even if this effects the film’s credibility or the trust we, as an audience, have in the filmmaker. As if Syria was not powerful enough as a conflict per se, as if it requires “enhanced” aerial views of hi-tech drone warfare. As if we need to be “immersed” in a situation akin to a video-game—“immersive” that catch-all, sexy and marketable vocabulary now applied to all media formats, from creative storytelling to factual journalism—in order to believe that, in fact, this is no video-game at all.

My uneasiness with “For Sama,” though, is not simply an uneasiness with its aesthetics. As a woman, I am not at ease with the film’s gender politics, either.

On the one hand, “For Sama” capitalizes on its author’s subaltern gender. Womanhood and motherhood are the main ingredients upon which the success of the film is orchestrated. We cannot but feel for the woman; we cannot but feel for the mother. The woman and the mother are universal tropes that make the international audience “see" and empathize for al-Kateab and her human cause, and yet disperse all things political behind the Syrian uprising. We do not see the political struggle of the Syrian people. We do see the struggle of a mother. Following neoliberal capital’s emphasis on self, we instead witness the personal struggle of an individual, completely losing track of the wider collective and political struggle, making the film so emotionally compelling and yet so politically empty at the same time. “For Sama” exploits the figure of the “woman” in the very moment in which it seems to give her agency. Womanhood and motherhood become tools in the hands of digital neo-orientalism and more subtle forms of colonial exploitation.

Syrian cinema: Motion picture in the age of transformation

14 April 2020

On the other hand, “For Sama” shows to what extent women—and particularly non-western women—are still subjected to white male colonial subjugation. The fact that the film is co-authored by a white English director, Edward Watts—who, so far, has mostly authored only TV works for UK television channels, with sensationalistic titles such as “Escape from ISIS”—seems to suggest that al-Kateab's work cannot be trusted enough to make the film internationally successful.

Very rarely has Watts spoken or elaborated publicly about his contribution to the film. His silent presence suggests that he is to be read more under the regime of a guardian, rather than that of a peer or co-author. Surely this is not just a problem with “For Sama”: there is trend in contemporary Syrian filmmaking of works co-directed in collaboration with a non-Syrian “peer.” I am not at ease with what I see as forms of neo-orientalism exploiting Syrian image-makers who have access to the “field" yet, in the eyes of western media industries, are probably not powerful enough to produce a storytelling that would be considered compelling and marketable to global audiences. The co-authorship becomes a softer form of colonial legacy and male guardianship toward subaltern and gendered subjects.

On womanhood and agency I cannot but think of another woman: Syrian-Kurdish filmmaker Wiam Simav Bedirxan.

At the time of the premiere of “Silvered Water: Syria’s Self Portrait,” the film she co-directed with established Syrian filmmaker Osama Mohammed, many objected that she had been objectified by her male—and much more famous—counterpart. Stuck in his exile in Paris, he would have asked her to be his “field" camera in besieged Homs, while directing her remotely.

“Silvered Water” accounts for this out-of-the-ordinary professional and human agreement; throughout the film we see the relation between the two unfolding together with the images, in a sort of impossible, hyper-mediated love story shot in bewilderment and confinement. The transparency of this unconventional relationship that unfolds thanks to the camera, and because of the camera, makes both Osama and Wiam equal stakeholders not only in authoring and owning the film’s images, but also in sharing the pain of bringing them to life.

It is perhaps this transparency that restores equality between two subjects who otherwise have a different cultural and socio-economic status, and makes them powerfully emerge from their shared pain.