A version of this piece was originally published in Arabic here.

Any possibility of real international military intervention to protect Syrian civilians ended in 2013 with former US President Barack Obama, through his now-failed deal with Moscow demanding that Assad hand over his chemical weapons.

Just two years later, the start of Russian military intervention cut away any chance that domestic opposition forces had of actually toppling the government.

And so Damascus' control over all of Syrian soil seemed just around the corner, as did its rehabilitation.

Then 2020 brought two new decisive chapters.

Watching the Caesar Act unfold, from the hometown of the Assads

01 July 2020

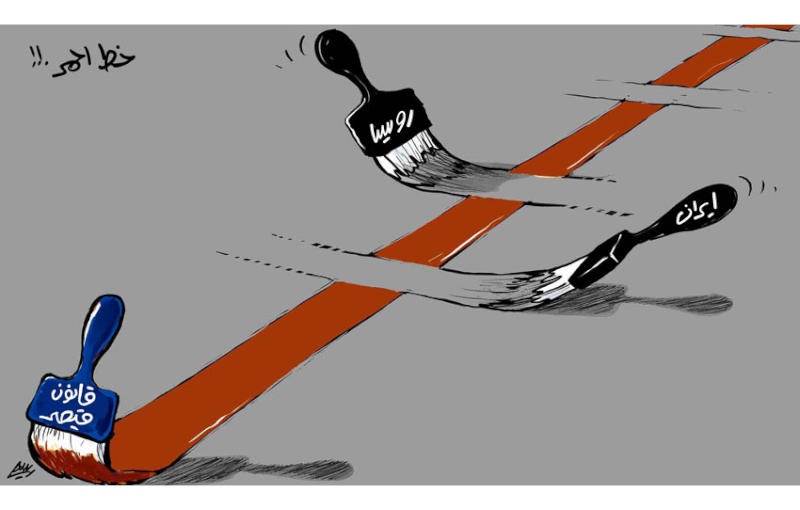

The first, in March, was the Russian-Turkish ceasefire agreement, which took shape after Moscow and Damascus failed to seize full control of Syria’s northwestern, rebel-held Idlib governorate and its border crossing with Turkey. The agreement halted Putin’s dreams to finally turn a page on the war in Syria, impose his conditions on Europe and the world, and handle Syrian reconstruction and refugee returns.

The second was the Caesar Act, which US President Donald Trump signed at the end of 2019, but finally went into force in June. The act, with its sweeping economic sanctions targeting the Syrian government and its friends, extinguishes any hope for the Russians to salvage Assad or reconstruct Syria under his rule. It also impedes regional and international attempts to rebuild relations with Damascus, as well as support Russian efforts to save what little does remain.

Playing cards

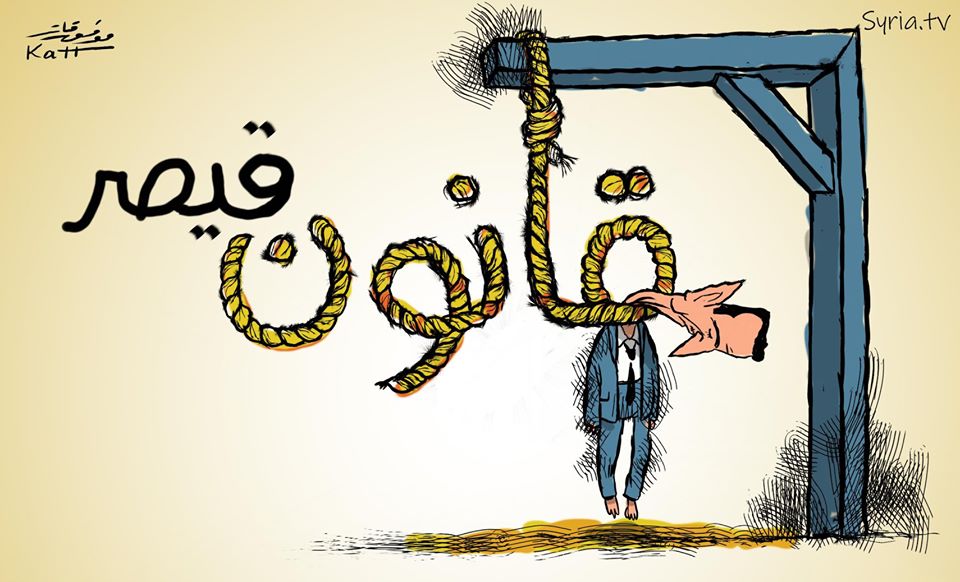

The sanctions, now in effect for nearly a month, represent a Damocles’ sword hanging over Damascus, making rehabilitating the government a mission impossible.

When US Special Representative for Syria James Jeffrey briefed journalists via teleconference on June 17, the day the sanctions were implemented, he outlined the six conditions required to halt the act: stop bombing civilians, release all political prisoners, allow human rights organizations into Syrian detention centers and prisons, lift the blockade on all besieged areas while allowing the entry of humanitarian aid and the free movement of civilians, ensure the safe and voluntary return of the displaced Syrians and guarantee accountability for the perpetrators of war crimes in Syria.

These conditions summarize most provisions of UN Security Council Resolution 2254, which Assad and the Russians have been circumventing since 2015. They include the formation of a reliable ruling body and redrafting the constitution through a committee, as well as holding transparent elections under international supervision.

In theory, the conditions set by the Caesar Act are sufficient to implement real political change in Syria, as the Assad regime cannot continue to rule if even one condition is met. Assad is known for abusing each of the conditions as tools for negotiation, control and blackmail, and as a pressure card on the Syrian people and international community. The act puts all these cards in one file.

An Israel card?

The second aim of the Caesar Act goes beyond Assad himself and includes any future ruling regime.

The US administration’s conditions to suspend implementation of the Caesar sanctions are not limited to ending Assad’s rule, sending refugees home and punishing war criminals.

Rather, the act aims at stopping Syria’s aggressive policies towards its neighbors in any future regime.

This last condition puts Israel and the whole peace process at the heart of the issue, and pulls the Israeli card out of Assad’s hands. The regime’s overt bragging about resistance to Israel was never for local consumption. The key message that it sent out to the international community, specifically in the wake of the outbreak of the Syrian revolution in 2011, is that Assad’s government is the only party capable of protecting Israel’s borders and maintaining the 1974 armistice.

The government wants the world to know that its extinction would not only jeopardize Israel’s security, but would also destroy all the calm that was built over four decades on the Golan Heights, with the introduction of any Islamist or Sunni substitute to the regime, according to Assad’s cousin Rami Makhlouf, who spoke to the New York Times about the issue in 2011.

But with the Caesar Act now in place, the US sanctions will loom over any current or future government that behaves aggressively with its neighboring countries—whether Assad remains or departs.

What about the economic implications?

The Caesar Act will have a lesser impact on Syrians living in opposition-controlled Idlib, as well as under the control of Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)-affiliated authorities in the northeast.

As in any hostage situation, the adventure of arresting the captor and freeing the hostages might end up killing the criminal and the victims alike.

However, Syrians who live in government-held areas will surely feel the impact. The poverty that already exists there will turn into deprivation and perhaps even famine. After all, the sanctions target entities or individuals who are either war criminals or rich and corrupt people seen as supporting the warmongering machine, without whom Damascus cannot function.

A ‘missing piece’ in the debate: As Caesar sanctions go into effect, are ordinary Syrians protected?

18 June 2020

The sanctions, which target this vital structure, will cripple the Syrian economy—but not because they are aimed at all sectors. Food and medication, for instance, are exempt from the act. Rather, it is because the remaining crumbs of the Syrian economy, from wealth and factories to companies and transactions, are all connected to this corrupt structure that is wolfing down the body of Syrian society, consuming everything.

Even UN aid to Syrians is not safe from corruption: of the $30 billion in aid per year, only 12 percent reaches the people it is meant to serve in government-held areas, according to Syrian economist Osama Kadi.

Hostages of Damascus

What is now clear is that the government is holding its people hostage to protect itself from collapse and accountability. As in any hostage situation, the adventure of arresting the captor and freeing the hostages might end up killing the criminal and the victims alike.

Such a situation poses an ethical dilemma. Syrians have been divided between advocates of the act under the pretext that it targets the opposition, and opponents of it (even from the opposition) who point out that it mainly affects everyday Syrian people.

This is nothing new. Similar dilemmas have accompanied Syrians in different forms since the onset of the revolution. Ever since the first protests, voices called for people to return home because the government is harsh and will kill them.

Then came dilemma over arming the revolution: some voices condemned bearing weapons, as they implicate everyone in murder, violence and sectarianism, while others believed the government could not be toppled peacefully. Then, a similar quandary surfaced with the Islamization of the revolution and the rise of Islamist factions, then yet another over support or rejection of US strikes, and so on.

With all those disagreements, still the same question remained: Should we revolt against a strong and murderous regime that enjoys international support, despite our knowledge that it will not only destroy its opponents but also their families, villages and cities; or should we remain silent to protect people’s lives and belongings, knowing that these people are paying a humanly intolerable price?

In the end, these moral questions are simply a luxury. The Syrian volcano has already erupted, and the price has been paid. Nobody can stop it except the government itself—a government that is holding its people hostage, and asking them to starve so that it does not have to kneel.

What an ironic, dark twist of fate it is.