Every summer up until I was maybe 13 or 14, I'd spend three months at my grandparents’ home in Talkalakh, a small town in western Syria. It was just north of the border with Lebanon, my home now as an adult.

I spent long hours during those endless, hot summers traversing town with teta, my grandma, mesmerized by how confidently and easily she navigated Talkalakh. She was a spotted female hyena trotting through her savanna kingdom. Hand in hand, we crossed from one end to the other, over the small hills and past the shrubs, for afternoon tea and coffee at one of her eight siblings’ homes. She would enter each house, her head held up high with amused chestnut eyes, aware that her arrival was about to cause a buzz of some sort. Everyone’s arrival, or so it had seemed to me, caused a stir. These gatherings were loud and filled with laughter, endless gossip and intense arguments that turned into tears, and breaks for prayer, and more breaks for cigarettes. There were always at least a dozen people. Cousins and cousins of cousins and cousins of cousins of cousins.

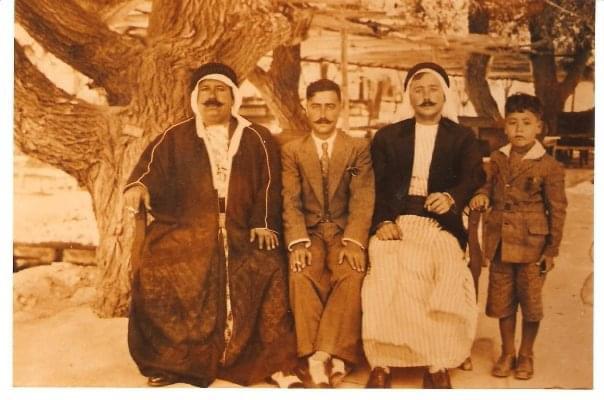

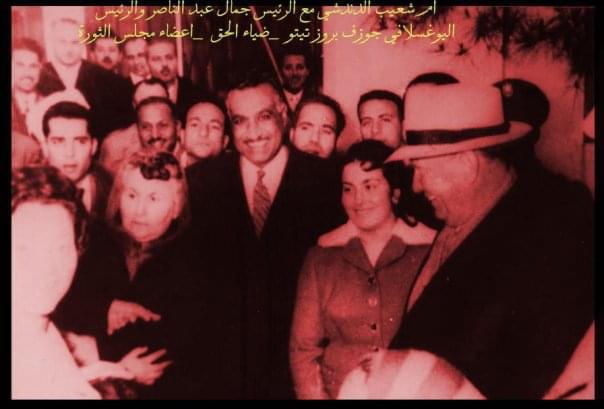

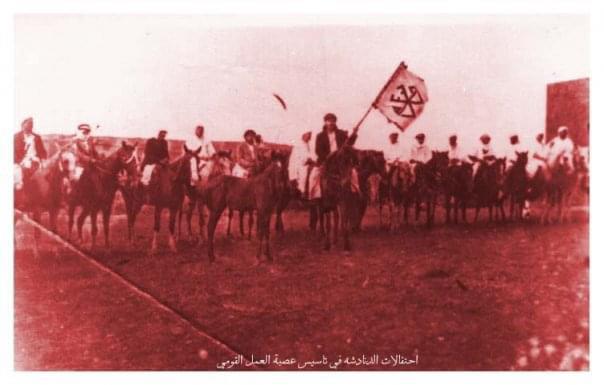

Talkalakh is the historic home of the landowning Dandachi clan, a family that enjoyed some political power under Ottoman rule. But after Syria merged with Egypt in the late 1950s, land reforms meant that the Dandachi family would lose most of its property and political standing. Both my grandparents from my mother’s side are Dandachis. Whenever we'd step into a house, my teta’s siblings would chuckle, “Here she comes—wife of the agha,” referring to my grampa with the honorific title given to many Dandachi men under the Ottoman Empire. Although the town had become quite poor over the years, Dandachis—all of whom are, in one way or another, closely related by marriage or kinship—still clung to their historic status as landowners, as aghas and beys and pashas, whenever a situation allowed them.

Teta knew everyone at the Talkalakh gatherings, and also everyone on the way there. Every corner we passed, every shop we stopped at, every “autocar” taxi we’d get into—she knew the background story of the person, who they’d actually loved before they married, how much money their cousin from their mother’s side sent them from Saudi Arabia (and whether the money arrived late or on time), whose house they had visited in Homs last week and whether there was tension on the dinner table and, if so, whether that tension was over a land sale payment that wasn’t split fairly between the siblings, or the fact that their daughter was speaking to someone from outside the Dandachi clan behind her parents’ backs. Talkalakh was that type of town. Everyone knew everyone, and everyone was as prying as they were concerned, their lives orbiting around Talkalakh like planets around the sun.

In 2011, only a couple of months into the Syrian revolution, my grandparents—along with most of the familiar faces that made Talkalakh my Talkalakh—picked themselves up, crammed their clothes and documents into suitcases, gave their homes a final, loaded gaze and fled.

They left towards a fate that, although painfully common in this part of the world, is impossible to ever come to terms with. In that first wave of flight, when hundreds of people crossed the border to nearby Lebanon or Turkey, it was as though an entire town ceased to exist. A transition neither gradual nor planned but rather, like an earthquake, sudden and disorienting.

By then, my grandparents’ children—my mother, aunties, uncles—had long found their own homes far from a small town that could not have offered them much beyond a loud, loving family and irrelevant Ottoman political titles. My mother married my Lebanese father, and they raised me and my brothers between Ghana and Lebanon. My aunties and uncles settled in Belgium, the Netherlands and the United Arab Emirates, with brief stops in former Yugoslavia.

The diasporic alienation of Syrian cinema

11 February 2020

From exile in Beirut, cinematic ‘beginnings’

17 July 2020

It’s not that my grandparents’ children had disconnected completely from Talkalakh. Every time they returned before the war, it was as though nothing had changed (and, really, nothing had changed). But after years of living outside the town they had grown up in, they had adopted new languages and found belonging in other communities. There were new smells and odd fruits, tram stops and a different flow of traffic, other things to attach their identities to. And this naturally excluded my grandparents—who, in their old age and with their rigid ways, cared to attach themselves only with Talkalakh and its people, the humor, the shows they watched, the weather, the local muezzin’s unique call to prayer, the walk towards their local butcher who knew just how they liked the minced meat and baked flatbread in their lahme b’ajeen.

In a way, my grandparents were extremely lucky in their displacement. Their children have class mobility, homes that could easily accommodate them and a safety net that is not fully at the behest of the UNHCR or racist governments.

But that did not mean my grandparents weren’t weighed down by the same grief as other Syrians when the war pushed them from home—the grief of being uprooted. From the very beginning, this is what teta despised, that because she had moved into my aunt’s villa in Dubai, surrounded by grandchildren and bougainvillea, and was only a 10-minute drive from the biggest mall in the world, she was not allowed to mourn all that she had left behind. She was one of the lucky Syrians. She had to aggregate her losses, the small and the big, and stuff them away in an underground chamber only she could access.

But one thing made the whole process somewhat easier: WhatsApp. In 2011, as Syrian families were struggling to make sense of their new lives, many of them insisted on staying connected online. At the start, most of the older generation struggled with their new smartphones and apps. My brothers and I would walk my grandparents through the process—click here; this is how you send a picture; no, no, be careful, if you share a status, then all your Facebook friends will see it. Several times, we would get phone calls in the middle of the night from my teta, anxious and agitated, because she’d accidentally sent a message to the wrong person or somehow deleted all her contacts.

Everyone knew everyone, and everyone was as prying as they were concerned, their lives orbiting around Talkalakh like planets around the sun.

Now, and especially after my jiddo, my grampa, passed away five years ago, teta has become as tech-savvy as me and is almost always on her phone. She is in multiple WhatsApp groups, and gets the best Syrian, Palestinian and Lebanese memes as soon as they’re out. She has mastered using voice notes to detail her recipes and antidotes for her grandbabies’ toothaches and flus.

It’s not that my teta, at age 73, is actually that inclined to using WhatsApp. It’s that almost her entire world—the updates, the extended stories, the jokes—has been transposed from the street corners of Talkalakh to her cell phone screen. Refugees her age, who do not have any interest in adapting to the new countries or systems they have found themselves in, are the real WhatsApp generation. On WhatsApp groups, the ones with their siblings and neighbors and grandchildren, they recreate their sense of community to keep it alive.

Willingly or unwillingly, when young people move to new places, they usually know that they must try to understand the new culture, engage with the “locals,” learn the language. But when you’re older, this inclination tremendously decreases. I don’t think it’s because older people are necessarily less curious. But with aching bones and hearing loss and a life spent acclimatizing and adapting, they would much rather be around what is familiar and comfortable. They are tired of new.

I can sense this even when teta sits with us, her children and grandchildren. Her unease hovers over the room like mist. We speak too much English (a language she never cared to learn) and discuss names and cities and TV shows she doesn’t know. If she were in Talkalakh, in her home, and we were having these conversations, it wouldn’t have mattered because we were in her space and she was allowing room for our chatter. For older Syrians, the past decade has disrupted the order of things, the plans they had spent their lives working towards. Teta doesn’t want to be 10 minutes from a mall where aquarium divers feed a giant shark just steps away from an overpriced Galeries Lafayette. She wants to be in her small home, with her frying pans and her TV and her noisy fan and the familiar spring insects that crawl on the living room’s window sill.

The large-scale forced displacement of people and the complete shattering of communities are nothing new. They were defining features of the 20th century, with the breakdown of empires, state formation and the rise of nationalism. They are fundamental parts of life, even, of being human. British-Pakistani novelist Mohsin Hamid writes that our ancestors moved “circuitously, sometimes in one direction, then in another, borne along by currents both without and within.”

In many ways, it took seeing my grandmother lose hers to realize that a community is the place where you are seen, where your belonging is part of the infrastructure itself. For my grandmother, the loss of her community translated into the loss of her place in the world.

I can’t help but think back to the Armenian genocide and the 1948 Nakba in Palestine, to the waves of refugees who fled Afghanistan, Lebanon, Kuwait, Iraq before the majority of people had access to smartphones or WhatsApp. What happened when they left home? How did they reach out to those they loved? The patience and pain a letter demanded, the unreliability and inaccessibility of phone landlines, the knowledge that you might never see your home again, perhaps not even in a photo.

Today, teta doesn’t have to wait months to hear from her brother who still lives in Talkalakh. He sends her photos of her old house, now occupied by a new family, whenever he passes by it. We cooked burghul b banadoura today, sister, your favorite, he sent her in a recent voice note. The jasmine tree outside your balcony is blooming, I picked a flower for you.

This back-and-forth messaging is nothing strange or even remotely romantic to us (if anything, it’s quite the opposite). Our phones and laptops, and by default WhatsApp (or whatever mode of social media communication we use), are a newly evolved organ in our bodies. We use them for work, activism, planning our outings, sharing memes and thoughts and articles. We’ve grown into a WhatsApp-reliant species.

But what I find fascinating when watching my teta and other Syrians her age unlock their phones and send videos to their friends, is that their relationships to WhatsApp are neither linear nor organic. The older generation of Syrians were suddenly thrown into a new world where WhatsApp had to become their dominant mode of communication, of remembrance. And they became the masters of it, like a city girl learning in a day how to pick out olives with mechanical grace.

Here in Lebanon, the October 17 uprising was, in large part, sparked by a tax on WhatsApp voice calls. Of course, the country altogether had been failing for a long time. But the night after the government had announced its plan to charge WhatsApp voice calls, people from all ages and social classes and backgrounds erupted across the country, chanting what Syrians chanted nearly a decade before: “The people want to bring down the regime.” In a country where nearly all public goods are stolen or exorbitantly priced, WhatsApp—which requires no payment, has no ads and is encrypted—at least feels free.

Amid economic collapse and pandemic, it feels as though almost every conversation I have with my friends circles back to the idea of community. A significant portion of my generation—one which has matured into a world of mass urbanization and environmental calamities, migration and refugeehood, Twitter addiction, loneliness and isolation—sees a stronger physical community as the answer to many of our questions. Whenever I mull over how I make meaning, it is somehow tied to my family, friends, or Beirut, a crushed city I insist on calling home.

My friends and I are all over social media, spilled across borders, living lives that cut through multiple communities, both virtual and physical. Still, we sentimentalize a time when everyone lived in a village and belonged to one tribe—a community straight out of Chinua Achebe or Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s fictional worlds. Where people lived door to door and cooked meals with enough leftovers for whoever decided to show up. As though those small communities were not riddled with social tensions, and the patriarchy and groupthink did not marginalize many, and competition and bitterness were not already deeply entrenched between nextdoor neighbors.

What is a community? I’m still learning what that can mean. In many ways, it took seeing my grandmother lose hers to realize that a community is the place where you are seen, where your belonging is part of the infrastructure itself. For my grandmother, the loss of her community translated into the loss of her place in the world.

No Syrian my age will feel true belonging again, she tells me, so we spend most of our time in our heads, remembering.

“My community is my memory,” writer and theater critic Hilton Als writes in a brilliant essay for The New Yorker, on his mother and loneliness among Black communities in the United States. In many ways, WhatsApp is an extension of that memory. Through it, we create new and decentralized communities that intersect across our many worlds, disrupting hierarchies. Our relationships with these apps, and the internet at large, is dialectical and cyclical. We know how quickly the world changes because of the internet, and we use the internet as a form of numbing, a form of agency and control, as a way of reaching out to one another to say: hey, we’re here, and somehow, against all odds, we exist.

I don’t think anything can replace human-to-human interaction. Holding a lover’s hands and feeling the warmth of their palms, laughing aloud with a friend when the song you both loved from your teenage years randomly plays at a pub, noticing the droplets of sweat on a stranger’s forehead like raindrops on a leaf. But human-to-human interaction is, in many ways, much more strained now than it once was. There is constant upheaval and movement, brimming with fear mongering and scapegoating and profiteering and climate change denial and viruses.

My work as a researcher, mainly with Syrian and Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, has shown me that many refugees, regardless of how long they’ve lived and mingled with the host community, will not feel as invested as they did back home. I wrote in my journal once, after a focus group with a group of Syrian refugee men, what one elderly man with soft brown eyes said: “You cannot love a place that doesn’t want you to even be in it.”

No one waits for WhatsApp to love them or need them. You are, when you’re using it, outside the gaze of the physical world around you, a physical world bent on crushing you.

A few weeks ago, some of my closest Lebanese friends and I got on a group call. A number of us were in Beirut, others in New York. It was after a particularly difficult couple of days in Lebanon: a man had died by suicide across the street from where most of us had lived when we were in university together, leaving behind a piece of paper that had written on it, “I am not a sinner.” Fuel is running out, electricity is rationed, migrant domestic workers are dumped on the street with no place to go, hundreds of households are hungry and desperate—all this while our government, which we have been protesting against for years, remains obnoxiously in power. In many ways, my friends and I are mere observers of all this pain, unable to fully claim it as ours because we aren’t economically or socially affected in the same ways as others, but also unable to avoid acknowledging it as a collective grief, a ghastly hole inside our chests.

We dialed into this group video call because we needed each other: the New Yorkers because they were so far from home, and the Beirutis because they needed to let the world know that home feels so different now, so foreign. None of us had been forced to flee. But in many ways, we are now trying to adapt to this disorienting nature of home, as though the city is plagued with a sour and clunky new language it doesn't want to learn.

The hours stretched, and the tears and swollen throats gave way to laughter and jokes and eventually a cheesy Fairouz song from our childhoods, “Zahret al-Madaeen,” a Rahbani Brothers tribute to Jerusalem written after the 1967 Arab defeat. Our hours-long call became something of a temporary community: transient yet anchored, complicated, painful. A space where all of us, even if only for a little while, felt seen and were held.

Editing by Madeline Edwards