“The ancient walls surrounding the old city of Raqqa contain endless stories. The houses support each other. One house is built atop another, and little rooms are built randomly on rooftops, making you feel that they’re about to fall.”

—Summer with the Enemy, Shahla Ujayli, tr. Michelle Hartman

Raqqa is a central character of Shahla Ujayli’s multigenerational novel Summer with the Enemy, with personalities that are by turns glamorous and shabby, open-hearted and cruel. In the novel, set to appear in Michelle Hartman’s English translation in November, Raqqa contains multitudes.

“There is not one Raqqa,” Ujayli tells SyriaUntold. “There is the city where I lived, and there’s the city I heard about in stories from family, neighbors, friends, fellow citizens. And there is a different urbanity in the history I’ve read in books, blogs, and documents, which I’ve also seen in museums and reflected in the eyes of tourists from around the world.”

“All these are faces or strata of a single city.”

Thousands of years before Raqqa was a marginalized, mid-sized Syrian city perched on a gentle bend of the Euphrates River, it was a Greek city known as Nikephorion and later Kallinikos, then a Roman one called Leontopolis. It has been called Raqqa since 639 or 640 CE, briefly serving as capital of the Abbasid caliphate some 150 years later.

Though short-lived, the grandeur of the Raqqan court was documented by the great historian and poet Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani in his 10th-century Book of Songs, which details contests and rivalries between Raqqan poets and singers.

But the central historical figure in Summer with the Enemy is not a court poet or singer, but the astronomer al-Battani (858-929 CE), who lived and worked in the city for four decades at the dawn of the Islamic Golden Age. He was said to watch the sky over Raqqa from atop a hill, correcting his Alexandrian predecessor Ptolemy’s errors, and calculating the elliptical orbits of the planets around the sun.

Ujayli grew up in Raqqa, attended university in Aleppo, and now works as a professor in Madaba, Jordan. She won the prestigious Almultaqa Prize for her short stories, and her third novel, A Sky So Close to Us, was shortlisted for the 2016 International Prize for Arabic Fiction. Summer with the Enemy was shortlisted for the same prize in 2019.

In A Sky So Close to Us, the main character lives in Jordan and has family back in Raqqa. But in Summer with the Enemy, Ujayli moves us closer to the city where she grew up, looking at it through the eyes of different personalities and generations. Most of the story takes place in Raqqa, although, as Ujayli notes, “Raqqa is no longer the city I knew.” She adds: “I try to get it back through writing.”

The Islamic State's 2014 capture of the city—and the city's grim tenure as de facto capital of the so-called caliphate for the next three years—is only one brief aspect of Raqqa’s long life. Yet that dark period looms over the novel, which opens with the narrator Lamees and her childhood friend Abboud in Cologne, Germany after her escape from the occupied city. Lamees must remind herself that she has left her hometown forever: “I decided to buy souvenirs, but then remembered that I was not a tourist—souvenirs are for people going back home.”

Still, the novel does not focus primarily on recent events, for which Raqqa became suddenly and gruesomely known six years ago. As Lamees looks at her friend and sometimes-lover Abboud, she is drawn back into memories of childhood summers, family stories, and the city’s multi-ethnic, multilayered history.

The Raqqa of 887, the Raqqa of 1987

Much of Ujayli’s novel is set in 1987, during the summer when Lamees is 13. That is when a German scholar named Nicholas appears in her life “and everything change[s].” Nicholas is only briefly in Raqqa, to research the traces of al-Battani the astronomer. But while he’s there, he falls into a relationship with Lamees’s mother and becomes the enemy of that long summer.

The family house, Lamees remembers, reeked of repressed desires: “to scream, to get divorced, to murder, to have sex.”

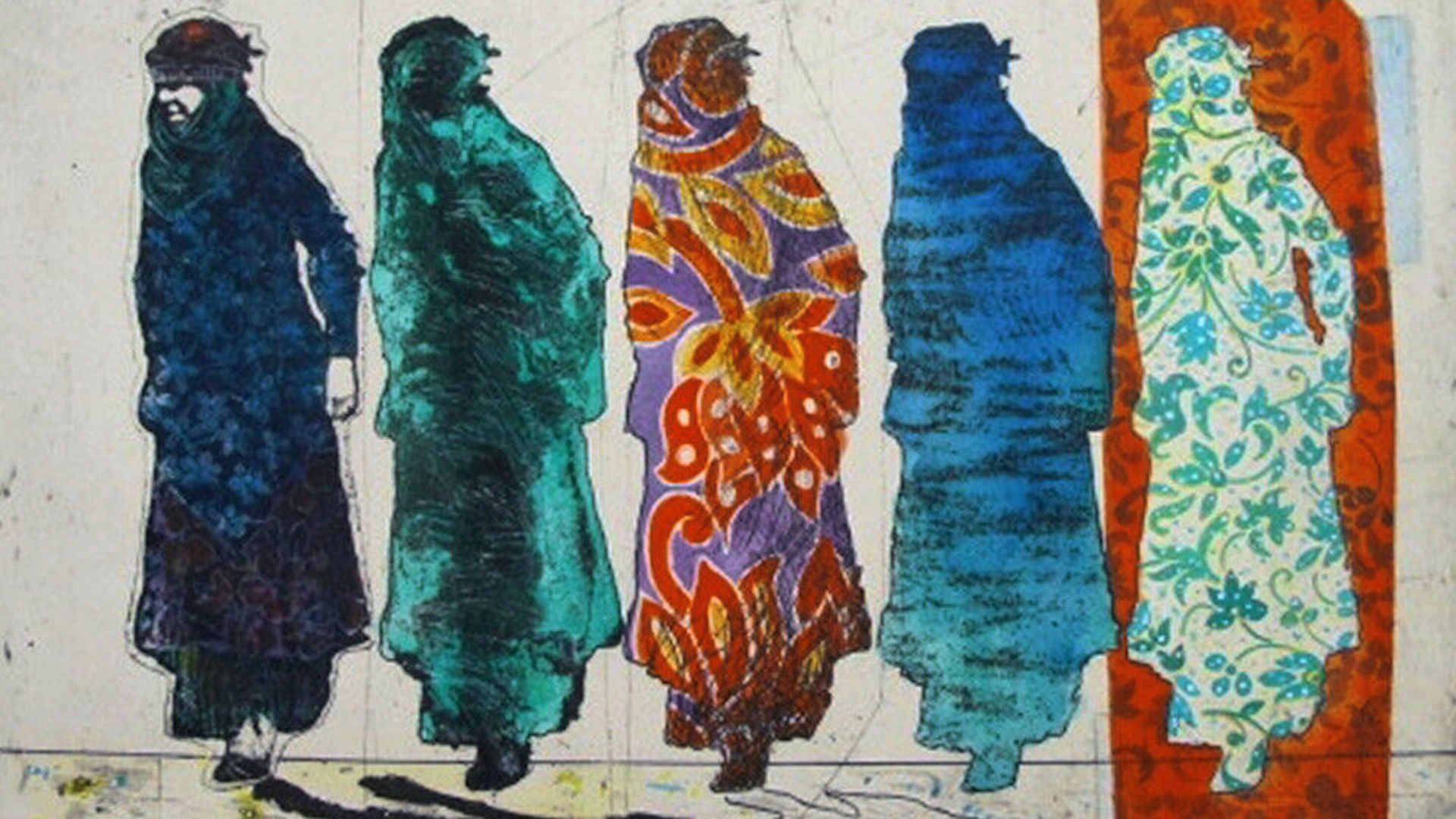

The Raqqa of Lamees’s 1980s childhood is rundown, even if filled with the beautiful ruins of bygone eras. Still, the ‘80s landscape is shaped less by al-Battani’s time than by the migrations and displacements of the late Ottoman period, the colonial-mandate era and Baathist rule. Each era brought its successive layers and communities. There is the Armenian Orthodox Private School, established in Raqqa in 1924 in the wake of the genocide that killed 1.5 million. There is Lamees’s own grandmother, who arrived from Jerusalem, after Lamees’s great grandfather was shot in the city in 1936, and her great grandmother committed suicide.

Ali did not board the last bus!

09 October 2018

Lamees’s grandmother fled Jerusalem and joined a dance troupe that toured the region, finally ending up in this “faraway little town shrouded in pitch-black obscurity.” After marriage, she went from being a famed dancer to a small-town housewife. But, after settling down in the Raqqa of the 1950s, she and her husband continued to travel. They owned an apartment in Aleppo and made sure they “had a joyful life of leisure, distant from the stagnation of Raqqa and its limits on pleasure.”

The most recent layer of migrants is the Eastern European women who arrived in the 1970s, having married Syrian men who studied or worked in the Soviet Union and its satellite states. Lamees’s friend Abboud is the son of a Syrian father and Czech mother.

Repressed desires

Lamees’s mother Najwa is born into this more conservative Raqqa, and grows up hearing insults about her own mother’s colorful past. Najwa tells her mother at one point that she’ll “never be anything more than an alumna of seedy nightclubs.” She then stumbles into an unhappy marriage and has one child, our narrator.

The family house, Lamees remembers, reeked of repressed desires: “to scream, to get divorced, to murder, to have sex.”

The Raqqa of Lamees’s childhood is also disconnected from much of the wider world. Yet she still manages to have adventures, and these moments from 1980s Raqqa are full of the transgressive beauties of childhood. Much of them are drawn from Ujayli’s own childhood in Raqqa, where she and her friends had little choice but to make their own fun.

“Imagine that until the mid-’90s, there was no taxi in the heart of the city,” Ujayli says. “Either someone who owns a car connects you, or you are deprived of your desire, or else you walk long distances in the heat or rain and mud.”

Re-imagining the enemy, re-imagining the past

Throughout this long summer of 1987, Lamees’s anger at Nicholas grows. It is Lamees who first stumbles across this middle-aged German scholar, while he is staying at Raqqa’s rundown Huriyah Hotel, home to an “unraveling red carpet...giving off a urine-humidity soaked smell, emanating from a busy, nearby toilet. Rusted bronze candlesticks hung on the wall, next to a portrait of the President of the Republic.”

Lamees and her mother help Nicholas rent a house and find his way around the city. He hires Lamees’s mother, Najwa, to assist him. At first, 13-year-old Lamees imagines that Nicholas should be in love with her, and her jealousy is directed at her mother. But later, as Nicholas’s attachment to Najwa grows, she fears her mother will abandon her and move with him to Germany. Though Nicholas leaves by himself at the end of the summer, he remains fixed in Lamees’ mind as an enemy.

Women seek refuge from society in a northeastern Syrian village, no men allowed

07 July 2020

That summer of 1987 is also when Muhammad Faris, the first Syrian astronaut, goes into space. Lamees and her family stay up all night watching as the astronauts enter the spacecraft at two a.m., and then blast off into outer space at five. They follow events on Syrian state TV, pressed together on auntie Maria’s couch. Not everyone is enthusiastic:

The announcer on the live broadcast showed us the first stages of the journey. His enthusiastic voice got everyone excited. We took our places, as he began praising our nation, especially Syria’s openness to the world, even far beyond Earth’s borders. Euphoria, pride, and fear were the emotions flooding my heart. I was truly afraid for the three astronauts, not only the Syrian one. My grandmother started grumbling, “Oh, here we go, now the hypocrisy mini-series begins. Where do these words come from, aren’t they tired of this yet?”

Lamees’s Jerusalem-born grandmother is never won over by Baathist patriotism, which sometimes makes her an embarrassment for Lamees. One year, young Lamees leads a march of children singing patriotic anthems to the state. She is proud to be “the officer who controls the momentum of the troops,” the one who “moves them like pieces on a chessboard.”

But when they reach the street beneath her grandmother’s window, all of this falls apart. Lamees’s grandmother “ruins the solemn and authoritative image that I’ve created for myself in the eyes of my colleagues” when she shouts: “Get out of here, take your friends and get out from under my window... go!”

For Lamees, “the only alternative to me bursting into embarrassing tears is to resort to a security threat, ‘I will turn you in to the mukhabarat and they’ll put you in prison!’”

It’s easy to imagine Lamees’s salty grandmother rolling her eyes at her granddaughter: “Put me in prison, bravo... bravo, well done. Put me in prison, but get the hell out from under my window!”

Their close relationship continues, although without ever discussing their differences. “I went back to my grandmother’s house in the afternoon. She welcomed me and put my lunch down in front of me as if nothing at all had happened.”

In the novel, Raqqa is a summer’s dream. It is briefly beautiful, and then it’s gone. Yet it is also preserved in memory.

At the very end of that summer, Lamees makes an even greater enemy: herself. Abboud asks her for a pair of her mother’s nylon stockings, which he pulls over his head like a thief. Then he sneaks up to her grandmother’s window, leans inside, and roars. When her grandmother is discovered dead soon after, Lamees believes she and Abboud have killed her. This belief grows into a central part of Lamees’s life story.

Her whole life builds around this moment. She is alienated from Abboud, and she stays in Raqqa with her mother instead of traveling elsewhere. She is still in Raqqa when Islamic State fighters take over the city, trapping her and her mother in their home.

It is a home very different from that of Lamees’ childhood summers. A new wave of foreigners has arrived. Raqqa is now a dark, frightening city in which Lamees’ new neighbor, a Tunisian man, has a “Toyota complete with a rocket launcher.” She and her mother attempt to flee the city in a caravan of relatives and neighbors, but her mother dies during the escape.

When Lamees arrives in Germany, she is alone.

Change in understanding

Once in Cologne, Lamees is forced to re-see Raqqa, herself, her childhood and the world.

She watches an interview with the astronaut Muhammad Faris, who is not the hero she remembers. Most importantly, she meets Abboud again, who is now a successful chef in Germany. He tells her that she is wrong, that they didn’t kill her grandmother. Before their prank, he says, her grandmother had already had a stroke.

Instead of feeling relief, Lamees is furious with Abboud for taking away the story that had organized her life. “I wanted to flee my whole entire life, the one in which I woke up every day trying to forget I had killed my grandmother.” But instead, she must come to grips with the fact this origin story was a lie.

Slowly, she begins to accept it. Then, in one of the novel’s most moving moments, she is also able to face Nicholas, her old enemy of that summer of 1987. Indeed, Lamees’s bravest act is not fleeing the Islamic State, but admitting she might be wrong and changing the way she sees her own past.

Ujayli, too, says she has changed the way she sees Raqqa.

“I used to feel that the city oppressed us, because it is marginal and simple, and far from the center, and it doesn’t have the weight of Damascus, Aleppo, Latakia or Homs.” Yet “now I find that everything that we did in Raqqa in our childhood and youth was great.”

In the novel, Raqqa is a summer’s dream. It is briefly beautiful, and then it’s gone. Yet it is also preserved in memory.

“I love the city yesterday, today and tomorrow,” Ujayli says. “I will always love it. And nothing can heal the wounds caused by its ruin, and nothing can compensate me for the loss.”

Editing by Madeline Edwards