This article is part of SyriaInFocus, a series on Syrian photography funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, with guest editor Sima Diab.

In 2012, Aleppo was afraid. Fighting had begun between pro-regime and opposition forces. The battlefield was unbalanced, with the regime and its military arsenal on one side and the light weapons of the opposition fighters on the other. Skirmishes were common, and so was the sight of soldiers in the city streets.

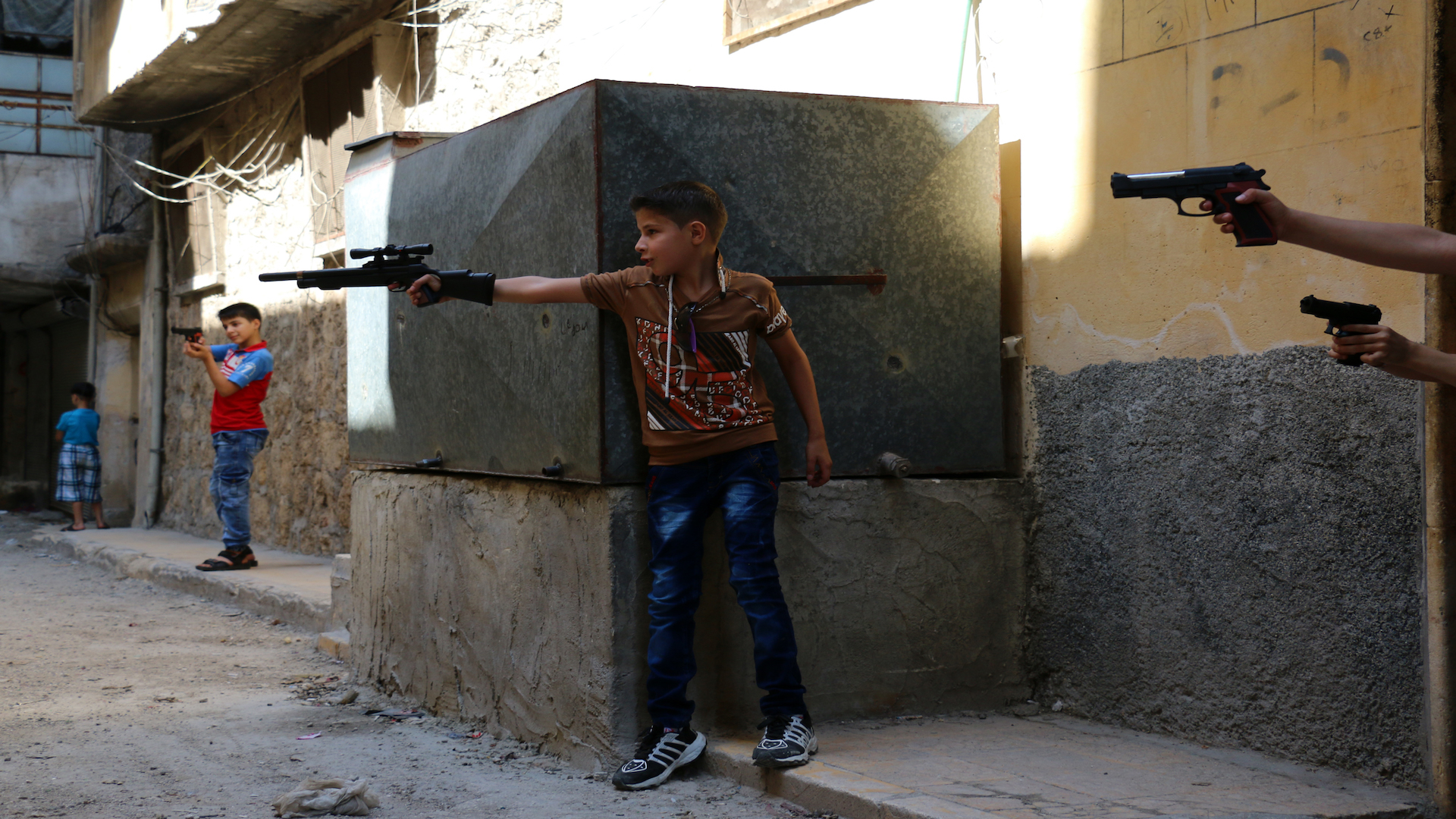

I took the following photo four years into the fighting, during the Eid holiday, in 2016. Just months later, regime forces would capture the district pictured here, in a deadly siege and bombing campaign that ended in mass forced displacement. In contrast, Eid is normally a time when people indulge in their favorite hobbies and leisure activities. Maybe the children did not choose this game, just as they did not choose to live here. There was little choice there; the dire situation was forced on everyone, with few alternatives, and the children of east Aleppo had even less.

I was a child too, 14, when the revolution started in 2011. I was shot twice in my hand the next year. I think people who live in conflict areas change, particularly children. The war affects their minds, and deeply changes them. I, too, was like that.

By the fifth year of the war, no matter where you looked in Aleppo you could see its effects: buildings, schools and streets were entirely destroyed; gutted cars and bombed-out stores became the landscape.

This young girl was familiar with her destroyed surroundings. And she was familiar with this red car. She used it like any child would use a swing set, but this was hers. This was the daily kind of play for children.

Life has a different meaning for children who grow up surrounded by war. Instead of going to schools, which were targets for bombing campaigns led by government forces, children spent their time playing in the rubble of buildings and bombed-out cars along destroyed streets.

Funerals became a daily occurrence for the residents of Aleppo. By 2016, when I took this photo, routine funeral processions were followed by nearby children. Many people were dying that year, victims of the heavy bombing over Aleppo.

Children became desensitized from death and violence. They played a game called “martyr,” which for them was a way to reinterpret the violence in their daily lives. The game entailed a funeral procession played out by children, where they carried a child who pretended they were dead along the streets.

Nour, an 18-year-old Syrian paramedic, lost his leg a year before, in 2015, after a regime barrel bomb attack near his home in Aleppo’s Bustan al-Qasr district. Despite his young age he understood that the word "disability" is a state of the mind and not the body. At the time he told me, "what makes me sad that I can no longer save people with the same energy and vigor I was before."

Nour and I were close in age, and rather than speaking about our first years in university, we spoke about disability from war.

Loai Mashhadi, now 25 years old, was a soldier in the Syrian army in 2012 and 2013. He defected and went back to his hometown, Aleppo, where the Free Syrian Army controlled his neighborhood. He saw daily bombing.

A few months later, he decided to join the Civil Defense. He was injured twice during his work in Aleppo, as the government’s bombing often targeted rescue workers like him. Loai now lives in Turkey. I once Skyped with him, and he shocked me when he cried right in front of me, as he was always the one I went to when I was feeling down.

In my youth and since I reached adulthood, I've expressed myself through photography. The children of Syria expressed their feelings too, through all their different ways of playing and surviving.

Survival was a daily adventure and the meaning of life is so great. In the love of life, in the love of immortalizing these moments of youth, to prove we were there. We want to live, we want to laugh, and it was unreasonable to sit and wait for death.