Germany is in its second month of a nationwide partial lockdown, with restrictions set to extend into January. It is a cold end to a year that has seen the virus wreak unprecedented misery across the world. Germany saw its highest number of daily virus deaths this past week, at 487 on Wednesday.

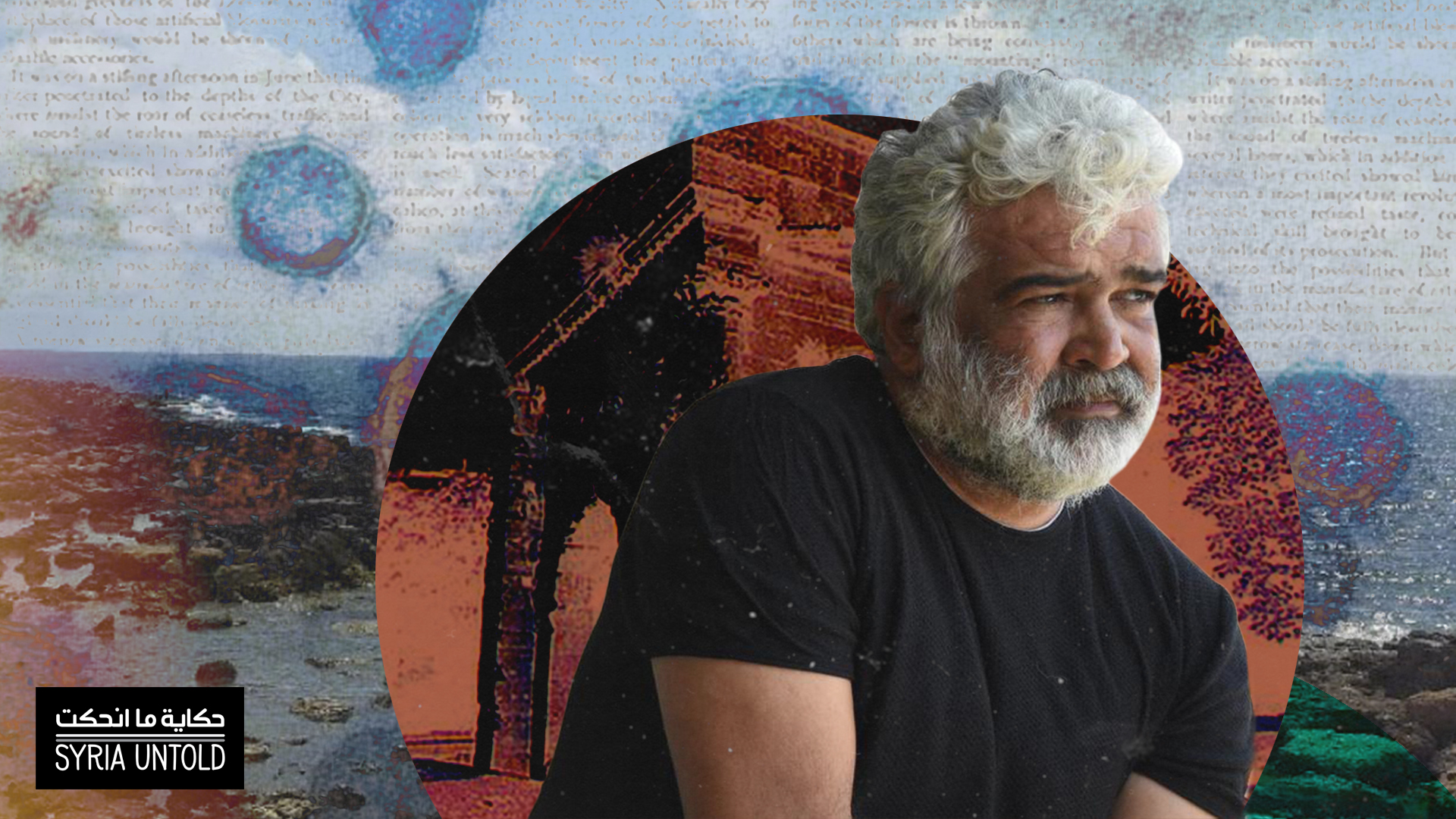

There, poet Ghayath Almadhoun says the past year has felt like a form of “prison.”

“The inability to travel now reminds me of when I was in Syria, before I left for Sweden in 2008. At the time, I wasn’t able to travel. I was paperless,” he tells SyriaUntold. Born in Damascus to an exiled Palestinian father and Syrian mother, he eventually gained Swedish citizenship. He now lives in Berlin.

“People in Syria were under Syrian regime bombing for a long time. When they went to the shelters, they went together. They hug each other. They leave together, they catch each other’s hands, they try to run away from the war by being together,” he says.

“The problem with the pandemic is that we have to run away, but isolated from one another.”

Syria’s year of pain, through the eyes (and pen) of Khaled Khalifa

21 November 2020

Raqqa, at the center of the universe

16 August 2020

Much of Almadhoun’s poetry weaves between similar contemplations of life and death, home and exile. His most recent poetry film, “Évian,” mourns a boat which, filled with refugees, has “died of a heart attack,” as the Mediterranean Sea itself “drowned.” In another poem, “The City,” Damascus is a mystic cemetery affirming the past lives of her many residents.

Almadhoun says he has yet to understand how this year has changed his views on life, and the role of poetry.

“Right now, I am not optimistic at all about the result of COVID-19. But I am very optimistic about what art will do to defend itself.”

This conversation was conducted over Skype, and has been lightly edited for flow and clarity. Almadhoun’s work can be found through his website.

First of all, what projects are you working on right now, and who or what is influencing you the most?

Everyone thinks that quarantine is a time for work, because now we can produce the things that we couldn’t in normal life. But the situation with me isn’t like that. I see quarantine as something inhuman, and out of the ordinary, and very heavy. It’s maybe the worst work period I’ve gone through in my entire life. I’m unable to work, to read, to produce things. This is because my writing and my life are tied completely to memory, to people, to travel; to the everyday things that are now lost.

I feel that I am imprisoned. The inability to travel now reminds me of when I was in Syria, before I left for Sweden in 2008. At the time, I wasn’t able to travel. I was paperless. I had no documents, because I’m from the Gaza strip, from the Palestinians in Syria whose families came in 1967 and not 1948. We didn’t have any documents, identification papers, passports, civil rights. So at the time, I wasn’t able to travel. I stayed in Syria under these circumstances until I was about 30 years old.

So the first thing with quarantine is that it forbade travel. I felt very strongly that I had returned to the time of dictatorship, the time when I was paperless. Life halted, and all my memories went back to that terrible time.

I’m trying to work as well as I can. I’m trying to write. But it’s not like before.

Who are the poets I’m influenced by? I can’t say that I know who I’m influenced by. But who are the poets I like? In general, I try not to be influenced by anyone. I like to have my own voice, to have my own dictionary.

But the poets who I like are the Iraqi poet Saadi Youssef, the Jordanian poet Amjad Nasser, who died last year. I feel strongly about these two poets. I’m not influenced by them, but I enjoy reading them. To be honest, I love poems more than poets. I love certain poems. More so than poets, because they change from period to period.

If you had asked me this question five years ago, I would have had many names to give you. But right now, I don’t know. Things have changed for me. Every year that goes by, the number of poets I love gets smaller. I don’t know why, to be honest. Most of the poets who were icons to me, I started loving them when I was a teenager, when I was younger. But each year the number shrinks. Maybe because I’ve changed, or because my writing changed or I’ve developed as an artist, or because I’ve met them in real life, or perhaps because of their political stances.

You’ve spoken and written a lot before on the idea of “home.” With the pandemic this year affecting travel in so many profound ways, have your feelings about exile and home changed?

It is very complicated, my relation to home, because my identity is complex. I was born in exile, to a Palestinian father who was exiled twice: first from Ashkelon in 1948 to the Gaza strip, and then in 1967, when he was arrested at age 17, and they exiled him to Egypt. He ended up in Syria, where he met my mother. My mother is Syrian, and I was born there. So I was born in exile, and I grew up as a Palestinian; not like the Palestinians who came to Syria in 1948, where all of them have a document. We don’t have human rights. We’re not allowed to work. So my identity was complex, because as a child I didn’t understand what Palestine meant and why we were in this situation. And my relationship with Syria was always strange.

I like to have my own voice, to have my own dictionary.

When I became 30, I chose exile. I ran away from the dictatorship. I went to Sweden, where I was invited for a poetry festival, and I sought asylum and became a political refugee. I remember every time people said to me: “You became a refugee,” I said, “No, I didn’t. I was born a refugee.”

I always see myself beyond borders. I belong to my friends more than to nationalism or countries. Yes, I’m strongly Palestinian and I’m strongly Syrian, and now I’ve become Swedish and I’m living in Berlin. But I prefer to belong to the things that I like: to my friends, to the things I believe in.

I like cities like Berlin or Brussels or Amsterdam or New York, these cosmopolitan, multicultural, diverse cities where identity, for any person, is lost to the big scene. I will continue to live in cities like these, because here I can find myself, in a city like Berlin where there is no identity.

Have the difficulties of the pandemic changed this idea of belonging, identity or home?

The worst thing about the pandemic is that it has changed our behaviors. People in Syria were under Syrian regime bombing for a long time. When they went to the shelters, they went together. They hug each other. They leave together, they catch each other’s hands, they try to run away from the war by being together.

The problem with the pandemic is that we have to run away, but isolated from one another. Some people describe this as heavier than a war. You have to be in a shelter, but alone. For me, this is hell. It couldn’t be worse than this. I can’t describe it, I really hate it.

I want to go back to normal life, and I’m sure we won’t ever be like we were before. It changed us.

How so?

In Syria, political prisoners spend long periods of time in prison; I have many friends who have spent more than 10 years there. Most of the prisoners reach a day where they become, as we say, istahbas. If I were to translate this into English, I would say “he became part of the prison,” or “the prison became part of him.” He begins to feel like he’s in a cocoon, and he finds it peaceful in there. Life begins to function, he has a routine. This happens to most political prisoners. And when they leave the prison after years, they have difficulty going back to normal life.

Has the pandemic affected your poetry, or your relationship to art?

It could be that it affected me. I’m writing a text about this kind of isolation, I call it “The Blue Marble,” the name of a photo that Apollo took when they were heading to the moon. They decided to switch the camera back to the Earth. That was in 1972. In that photo you can see Africa and the Middle East, and it was dark blue.

I always see myself beyond borders. I belong to my friends more than to nationalism or countries. Yes, I’m strongly Palestinian and I’m strongly Syrian, and now I’ve become Swedish and I’m living in Berlin. But I prefer to belong to the things that I like: to my friends, to the things I believe in.

During quarantine, I was thinking a lot about this image. It shows how small we are. It shows us as the size of an apple. Everything we have and that we fight for, everything we know, is inside this photo. This pandemic showed me how weak we are. So I began to write about this, and I haven’t finished yet. I’ve been working on [this poem] for almost eight months. And I don’t know how to end it. Maybe I will edit it all, or erase it all or delete it or something.

But what I want to say is: yes, [the pandemic] has impacted our way of thinking. So of course it will empower our writing and creative work. But don’t forget: the museums are closed. Book releases have stopped. Poetry festivals, culture festivals, literature festivals; everything connected to culture has stopped. Actually, for example in a country like Sweden, it’s an open country, it’s the only country where there’s no lockdown. But everything connected to culture, they close it. Because the culture is very weak, and now the right wing is everywhere. So they didn’t close the malls or anything connected to money. But if something is connected to culture, they tell you “oh, it’s a pandemic” and they shut it.

We are workers of culture; we are poets, artists and musicians. But we don’t have anything to quench our thirst. I wish I could go to a festival, to a culture evening, to discussions, to see museums. So of course [the pandemic] will have an effect on our work. In what way, I can’t give you any answer because I really don’t know. But for a person like me, whose writing is connected to his memory and his experience, of course it will appear in text. I don’t want it to be in a direct way. I don’t like that. But of course it will appear. It will find its way to the text, even if I write it and delete most of the things that I don’t want to appear from the time of corona. It will remain: the effect of it, the sadness of it, the depression of it.

What role do you think poetry and art can really have during a time of so much death, and so much suffering and illness?

I don’t want to say that art in general is more important than anything else. That would be unfair. But I feel that artists in general bear witness to any period we pass through. So of course we need doctors, we need engineers, we need supermarkets.

But art is the thing that will remain, [for people] in the future to judge and measure us, as we measure all of civilization before us by their cultures, by what they gave us. It’s very important to say it, without being selfish. Yes, artists are important in this period.

In the Qur’an, it’s mentioned several times that Muhammad is not a poet, and he’s not crazy. And always they mention those two together: poet and crazy. Think about why they put the craziness and poetry together. What is the relationship between being a prophet, and being crazy, and being a poet? I don’t know, but it’s there. Are the poets some kind of messengers, or are they crazy? I don’t know. But there is something about poets; I’ve been surrounded by a lot of poets from all over the world, and I guarantee you: yes, they are insane.

You’ve previously said that you are pessimistic, like the 11th century Syrian poet al-Maari. What, specifically, are you pessimistic about?

There is a Palestinian writer, Emile Habibi, from Haifa. In 1974, He wrote a novel that he called: Al-Mutasha’il. He created this word, and from that moment we added it to the dictionary. In Arabic, we have mutasha’im [pessimist] and mutafa’il [optimist]. He took half from one and half from the other, and created mutasha’il. He is half pessimistic and half optimistic.

I am mutasha’il. In many things, I am optimistic, and in many things I am not. And this switches very quickly sometimes, especially in crazy times like these.

Right now, I am not optimistic at all about the result of COVID-19. But I am very optimistic about what art will do to defend itself. Every time you have a new problem, you find a new way to defend yourself. And during the last big pandemic, the Spanish flu pandemic in 1918, it was different. There was no social media, no communication like this.

Now, it’s different. Now I open Zoom to people all over the world, we open some wine, and we hang out as a way of defending our human bodies and human minds. This never happened before COVID-19. We never sat in a room on Zoom that everyone could enter, and open some whiskey or wine, and be in a discussion. But as a way to defend ourselves, as a reaction to the pandemic, we began to do this. And it’s very strange. Some of the poetry readings I did in the first [part of] the pandemic, I did in Berlin. I’m used to doing readings where some people come, sit, buy a ticket. But in one [Zoom] reading, which we streamed live on Facebook, there were 2,000 people watching from all over the world. I’ve never been in a reading where there are people all over the world watching. I don’t say this is good; I really don’t like it.

Is there something good to be said about this, though?

I don’t think we should use the word “good.” There’s nothing good with COVID-19. We could say that we invented fine ways to survive.

In your poem “The City,” you write, about Damascus:

“She is the earliest cemetery, which people have celebrated as evidence that memories are real.”

Throughout this poem, death seems to be a natural part of life, a natural part of the balance of home and cities and civilization. Can you talk more about this?

Yes, somehow this is what I meant, but at that time. My relationship to death was totally different. I wrote this poem before my brother was killed in the Syrian war. He was killed in 2016. And when he died, I hadn’t seen him in eight years because I was in Sweden. I missed him. His death made me see death in a different way. I saw that he was gone, and that death took his place.

We were six people: father, mother and four children. And then my brother Ghassan disappeared. We didn’t find his body; he got killed. And then death came and took his place, and stayed with us. I could see him every day. Every day I remembered my brother.

Before, when I wrote this poem, I still had the romantic idea of death. Now, it is a realistic idea. I see death as part of the family now. He’s one of us because he’s there. He’s sitting in the place of my brother.

I always change my ideas about everything. One day, this thing will shrink. As we say in Arabic: everything begins small and grows, but the crisis begins large and shrinks. With time, the death of my brother will remain as a memory somewhere in me, and then I will be able to see it in a different way.

Has this past year also impacted your view of death, or how you write about it?

The Syrian war changed my relationship to death more than the pandemic. I saw the pandemic as threatening for us as humans. This doesn’t scare me. If you told me there was a huge asteroid heading towards Earth to crash, and that we will disappear like what happened 65 million years ago with the dinosaurs, I would not feel afraid, or anything. That’s because all of us will disappear together. So for me it’s okay. But the death of war, where the target is only one group; it’s totally different for me.

You think about death all the time, in a certain way. And then you find yourself in a war. Yes, I was in Sweden, but my family was under the bombing. And I began to lose people one by one. Uncles, brothers, friends. Every day. It’s insane, if I show you my Facebook. I have hundreds of people who are dead now. Killed by the Assad regime. And today will be the birthday of this person, tomorrow the birthday of that person. And I don’t want to remove them, because we have messages between us on Messenger, we have memories.

What about life? How has all of this changed how you write about life?

I don’t know yet. Maybe it will change something in my dictionary. Times like this change our dictionaries. I’m longing to see it from outside; I mean from [the perspective of] normal life. I’m longing to hear that this is finished, we controlled the virus, we have the vaccine and it’s gone. And then life becomes normal again. And then I can look from outside, from that time, to this time, as an outsider. And then I can see what is different. If there’s any difference in our creative way of writing or making art, it will appear later when we come back to normal and we can judge it.

But right now, I don’t know.