This is how one story goes. It was the early 20th century, maybe 1915, amid Lebanon’s vicious famine. Ottoman authorities were enforcing safar barlik, mandatory conscription of Lebanese, Palestinian, Syrian and Kurdish men to fight for them during the Great War. They say these were some of the worst years for Bilad el-Sham, that Beirut and its surrounding mountains were like shriveled fruit, wrinkled and helpless. Locusts had destroyed everything—the olive trees, the fruits, the vegetables, the maize. People were starving, dying on the streets from deadly diseases, their stomachs empty and bloated, lice powdered over their bare bodies.

Word began to spread of an Italian ship headed to Beirut, the Rosana. It was said to be carrying food. Women began singing for the ship’s arrival in tired monotones. Every day, the story goes, the men went to the Beirut port and stared at the sea, hoping to find a moving object in the distance. They eventually gave up. News had arrived that the Allies had imposed a naval blockade on the shores.

By then, the women’s singing had become urgent and instinctive, like prayer. `Al Rozana, `al Rozana, they sang, until the men and children soon joined. On the Rosana, on the Rosana.

Their song soon reached Aleppo, which had been spared the famine. The merchants of Aleppo responded almost immediately. Under the nose of the so-called saffah, the butcher Jamal Pasha, the city’s merchants managed to smuggle piles of wheat and lentils and cooking butter in caravans, arriving in Beirut by night.

We all played the telephone game when we were children: téléphone cassé in Lebanon, hatif al-laselki in Syria. The wireless telephone. The French call it téléphone Arabe. You gather in a circle with your friends and cousins in the playground or on your aunt’s cold kitchen floor, and someone is given the task of coming up with a sneaky and controversial message to pass along to the last person.

My childhood friend, now a ghost

18 September 2020

The first player whispers the message into the ear of the person next to them, and the second person to the by-now puzzled third, and so on. The point is to burst into laughter by the time the last person in the circle has received and announced the message because, more often than not, it has been disfigured.

Human recollection or story-telling is unreliable, divinely so. In his novel “Tomorrow in the Battle Think on Me,” Spanish author Javier Marías writes: “Once a story has been told, it’s anyone’s, it becomes common currency, it gets twisted and distorted, no story is told the same way twice or in quite the same words, not even if the same person tells the story twice, not even if there is only ever one storyteller.”

This is how another, slightly different, version of the story goes. By the winter of 1916, the worst fears among Beirut’s traders were confirmed. A huge Ottoman ship called the Rosana had arrived at the shore before sunrise, carrying grapes and apples at the cheapest prices possible. Already, the price of wheat in Beirut had skyrocketed to 40 uroush per rottol from five uroush earlier in the year. The queues for bread outside bakeries went on and on, hundreds standing in line on stick legs. Once they bought it, the bread itself was burnt and hard as a stone.

The Ottomans wanted to completely deplete local production and flood the market. This was at a time when Jamal Pasha had cut all supply lines in the region, unless they were being used for the Ottomans’ military purposes. The seas were blocked by the Allies and the railroads by the Ottomans, and everything had been put on hold for the war. No one dared speak out against the Rosana. How could anyone forget the image of Jamal Pasha’s execution of anti-Ottoman intellectuals and Arab nationalists in Damascus and Beirut?

Merchants were said to have stood not too far from the dock. The rising sun struck their tired faces like a smirk. Their eyes squinted, trailing the men as they unloaded the crates from the ship. Each crate was a weight added onto their shoulders. What were they to do now, when everyone would buy from the Ottomans? And who could blame them? This was a time of hunger.

But by noon, Aleppo’s merchants had arrived with mischievous smiles on their familiar faces. From a distance, they announced with loud, gruff voices that they had come to buy all the grapes and apples from the ship, at a higher price than the Ottomans had demanded, in a bid to save Beirut and Mount Lebanon’s traders from bankruptcy. After they had purchased the fruits, the Rosana retreated into the sea like a shameful old man.

“`Al Rozana” is one of the best known folk songs in the Levant. Like a precious hand-me-down, the song has been passed on from one singer to the next. Sabbouha, Fairouz, Sabah Fakhri, Lena Chamamyan, Amal Murkus, Sanaa Moussa, Charbel Rouhana, Hawa Dafi have all sung it.

There is no real agreement about where this song comes from. The most common guesses are based on stories from the terrifying maja’a, or the famine, in Bilad el-Sham in the early twentieth century, when a ship with the name of Rosana was said to have docked at Beirut's port.

My father says the ship had actually stopped at Batroun's port. This is what his grandmother, Rashideh ‘Atayeh, had told him. She would sing the song in his ear when he was a little boy, sleeping next to her. All his stories of the famine come from her: her impoverished family had left Jbeil for northern Lebanon in 1917, fleeing, she said, only after they had eaten their last bundle of bread crumbs. After arriving in the town of Halba in Lebanon’s Akkar region, they stayed at the house of Akkar’s respected Sheikh, Sobhi Sayed. Sobhi and Rashideh ended up getting married three years later, much to the dismay of Halba’s people who found it abysmal for a sheikh to wed a young Christian woman. What my father remembers of my great grandmother’s version of the song is that the ship’s cargo had actually come from Aleppo, and included wheat for the people of Mount Lebanon. But he’s not too sure.

Raqqa, at the center of the universe

16 August 2020

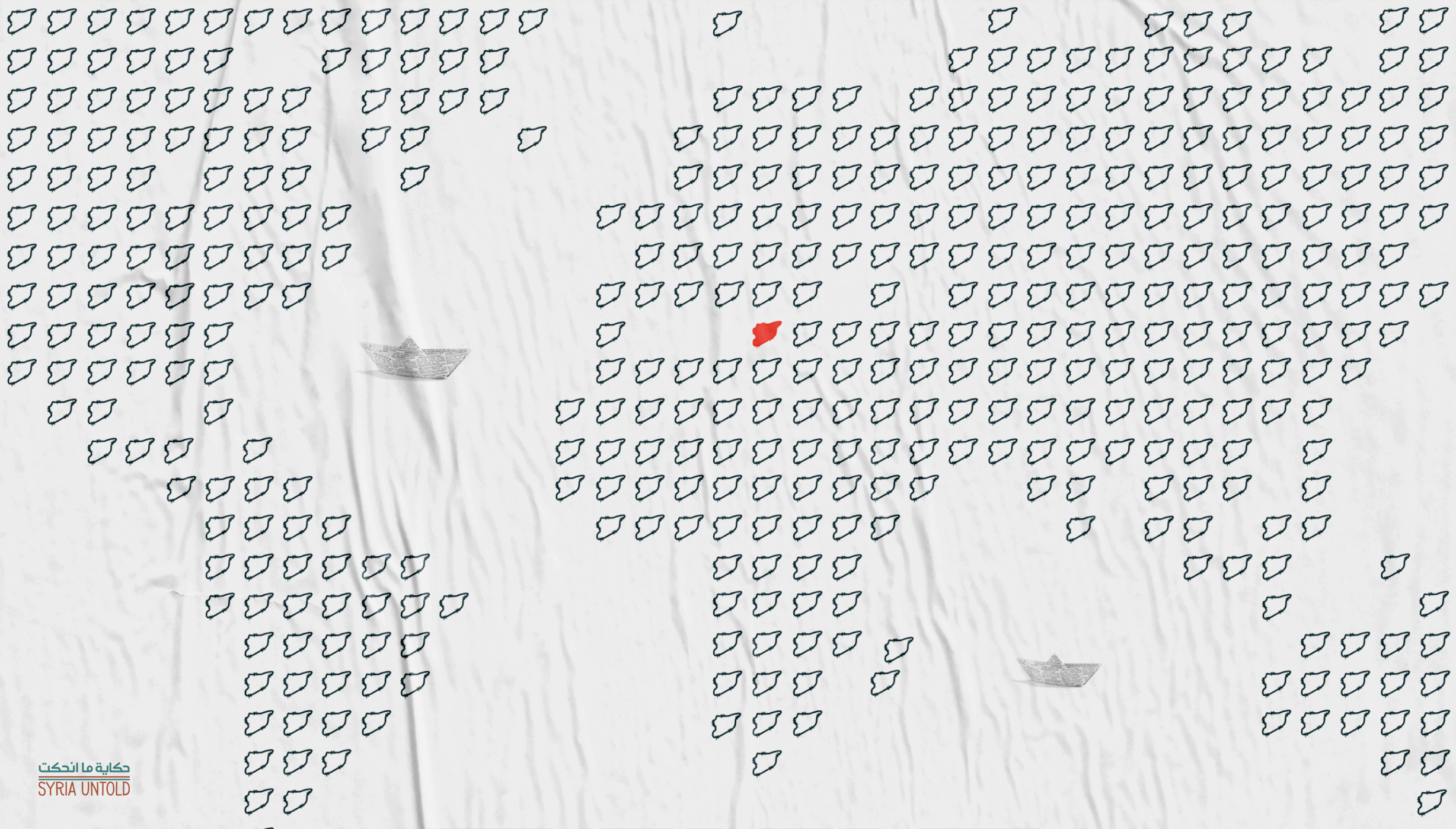

Distorting Syria

23 July 2020

Other narratives that I found through my research—which, admittedly, was based on academic articles just as much as YouTube comments and conversations with older family members—are those of tragic love stories.

According to a very ardent YouTube commenter, the song is based on Palestinian popular heritage. There was a young couple in Palestine, who would gather by a water spring in secret once a week. The girl was from a village near Safad, while the boy was from the city of Safad itself. The girl came from a poor, peasant family, and the boy from an elite, merchant one, and their marriage would be impossible. When the girl’s father found out about her secret meetings, he attacked the boy and his father, banning them from ever returning to the village. And so Merchant Boy traveled to Aleppo instead, where his father had wanted his son to marry the daughter of a rich trader to expand his business. After he left, Peasant Girl would dress herself in grief every night, singing for him to dull the ache.

Others say rosana (or razouma) in the Iraqi dialect is a small opening in the wall between two houses, and that the song is based on a love story in Mosul, where two young neighbors would speak late at night through the hole separating their homes. After the woman’s parents found out about this illicit love affair, they closed off the opening, and prevented their daughter from speaking to her lover. Her lover, unable to bear this new reality, travelled to Aleppo, and sang this song in the desperation of longing.

Levantine folk music is about community, mountains, the sea, wars and exile, peasants and land, lovers who traveled to faraway lands and never returned. Spawning from one individual story, or one collective sentiment at a time, it comes to reflect and perform micro-histories in the most delicate and tender of ways.

And so do the origins of “`Al Rozana” really matter? Towards the end of Charbel Rouhana’s version of the song, the background choir sings, “Wallah ma `rifna shu `emlet el Rosana” (I swear, we don’t know what the Rosana even did). Oral narratives allow us to reclaim or rewrite histories silenced by colonialism and patriarchy, but they are not enquiries into historical accuracy and facts. That is not their point.

For me, folk music and oral narratives are a way to embody the past, even if only temporarily. To spin old stories that help make sense of newer ones. To allow emotions we desperately need at a given moment to make their way into our bodies, from our land and ancestors, and onto those who come after us some day. In his epic novel “The Hakawati,”—or “the storyteller,” an intricate tapestry of legends and parables—Rabih Alameddine writes: “What happens is of little significance compared with the stories we tell ourselves about what happens. Events matter little, only stories of events affect us.”

After the murderous explosion in the Beirut port on August 4, it was commonplace to read headlines or hear people say things like: Beirut looks like Aleppo did in 2016. That like in Aleppo, the buildings in Beirut had become rubble, the streets hollow like an abandoned tunnel, the city only a flicker of what it once was.

Comparing Lebanon to Syria, I think, is more dangerous than helpful. Nothing can compare to the Assad regime’s massacres, to the past nine years in Homs, Aleppo, Deir al-Zor. But there is suffering in both countries. Everywhere you go in Lebanon, there is a sense of inescapable and cyclical trauma; every conversation you step into is a reminder of what has happened over the past few decades, of what is to come.

This past November, around 300 Syrian refugee families fled the northern Lebanese town of Bcharre by night, heading to Tripoli. This was after Bcharre’s “locals” went on a rampage, torching houses and assaulting Syrian families. A Syrian man had brutally shot a Lebanese man in a personal feud, and groups of men responded to the crime by collectively punishing all Syrians living in Bcharre.

A father of six, Mohamad, who suffered severe bruises on his back from the assault, told me that his family had left all their belongings behind. It was as though they were starting from zero again, seven years after having to do the same thing in Idlib, his home city. He kept repeating that many people in Bcharre continued to check on him and his family, that the attackers do not represent all the townspeople. Lebanese in Tripoli had offered blankets, food and financial assistance. Some had even come from Beirut to help the stranded families.

But this is not an isolated event. Syrian refugees in Lebanon have faced one brutal act of racism after the other: curfews imposed on them by local authorities, systematic targeting by security officers, tented settlements set ablaze in the middle of the night by host communities and continuous scapegoating by corrupt and fascist politicians.

I don’t bring this up to say: look where we were one century ago and look where we are today, or that Syrians are better than Lebanese because this lovely folk song alludes to the courage and selflessness of Aleppo’s merchants.

Folklore, to me, isn’t meant to function as a parable or moral lesson. And as much as I would like to preach Syrian-Lebanese solidarity, I know that depending on who you ask, which community you speak to and how you frame the question, the reasons behind these tensions differ. My friend Nawal Muradwij, who researches collective trauma in the Levant, tells me that such multigenerational pain disrupts a community’s ability to form a coherent public narrative. Storytelling, she says, is a way for groups to emphasize certain norms and values, but trauma, especially when unaddressed, disrupts that process. It makes it difficult, sometimes even ineffective, for folklore to acknowledge the proximity and interlinkages between Syrians and Lebanese, or the communities in the region more generally.

Since the famine in 1915-1918, when “`Al Rozana” was said to have first been sung, much has altered. This was before Sykes-Picot, before the French Mandate, before the military coups and the civil wars, before the Assad dynasty, before 2011. And who knows if Aleppo’s merchants ever did come?

Communal grievances are so deeply entrenched that individual empathy is one thing and group empathy another. It is easy to imagine a decaying railway connecting Beirut to Damascus, easy to talk about how we all share the same sea and music and food, easy to say our collective fate is in each other’s hands. But identity politics and displacement and occupation and war wound in a way that renders music and poetry vain.

And yet, the shared folklore in our region, in Lebanon and Syria and Palestine and Jordan, is one of the starkest reminders of our connectedness, a reminder of how music and poetry traveled from one city to the next over a century ago, bringing with them stories of lament and celebration, spreading with them the the Aleppan qudud (qudud al-Halabiyyeh), the mawwal, and muwashahat.

German playwright Bertolt Brecht wrote, “In the dark times/Will there also be singing?/Yes, there will also be singing./About the dark times.” In March of this year, a group of musicians from Aleppo rewrote ‘“`Al Rozana” as a playful ode to COVID-19. And in an academic article on Israel’s Nation-State Law, Nadia Ben Youssef and Sandra Samaan Tamari write of a group of Palestinian activists who visited the Water is Life protest camp in Louisana in 2018, a demonstration of solidarity with indigenous communities. Their visit was also a way to frame the Palestinian struggle as an intersectional, decolonial one. After hearing about indigenous women’s actions to protect their lands from environmentally devastating infrastructure, a Palestinian woman broke into the song “`Al Rozana,” and the article documents how “at the pipeline protest, our group of indigenous and Palestinian women cried and embraced each other.”

Now, less than a month after Syrian refugees were viciously expelled from Bcharre, at a time of complete collapse in both Syria and Lebanon—I listen to “`Al Rozana” and think of people from Beirut and the Ottoman-administered Mount Lebanon mutasarrifiyya waiting, queued in a long line somewhere near the port, for something to relieve their pain, and the people of Aleppo arriving, in dramatic fashion, at the break of dawn or before noon, to help them. A brazen act of solidarity. A love letter of sorts.

Editing by Madeline Edwards