SyriaUntold is publishing this article as part of the #ForJustice campaign, in partnership with the Institute for War and Peace Reporting. A version of this article was first published in Arabic here.

When I told them I was cold, they warmed me with slaps

The hours spat their seconds in our eyes.

-Syrian poet Golan Haji, from Disappearances

“I stored the stories inside me, to tell once I got out,” Abir Farhoud recalls. Though she now lives in Germany, nearly a decade ago she was detained in Syria’s Branch 215 and Adra prison, where she witnessed numerous rights violations. Speaking with SyriaUntold and the #ForJustice campaign, she remembers a fellow inmate who was severely tortured by security forces before they forced her to appear on a pro-government TV station. Once live, she was made to falsely confess to aiding “jihadists” and performing “sexual jihad.” The woman’s father later visited her in Adra prison, Farhoud says, and spat in her face. He told her he would slaughter her if she made it out of prison alive, as she had dishonored the family.

“As time passed, people began flocking to our house, and congratulating me on my release. I refused to be called a hero. I was not one. I told the families of the arrested people from my neighborhood that they were with us in prison. The next morning, I shaved my head completely, after my mother spotted lice on my bed. I only stayed home for two days. I then moved into my sister’s house (she was like a second mother to me). It was empty, since she had moved out of the house and gone to a Kurdish city in the north two days before my release from that grave. I stayed at her place for four days, away from all the noise and alone with my solitude. How I wished to return to prison! I started to believe prison was freedom!”

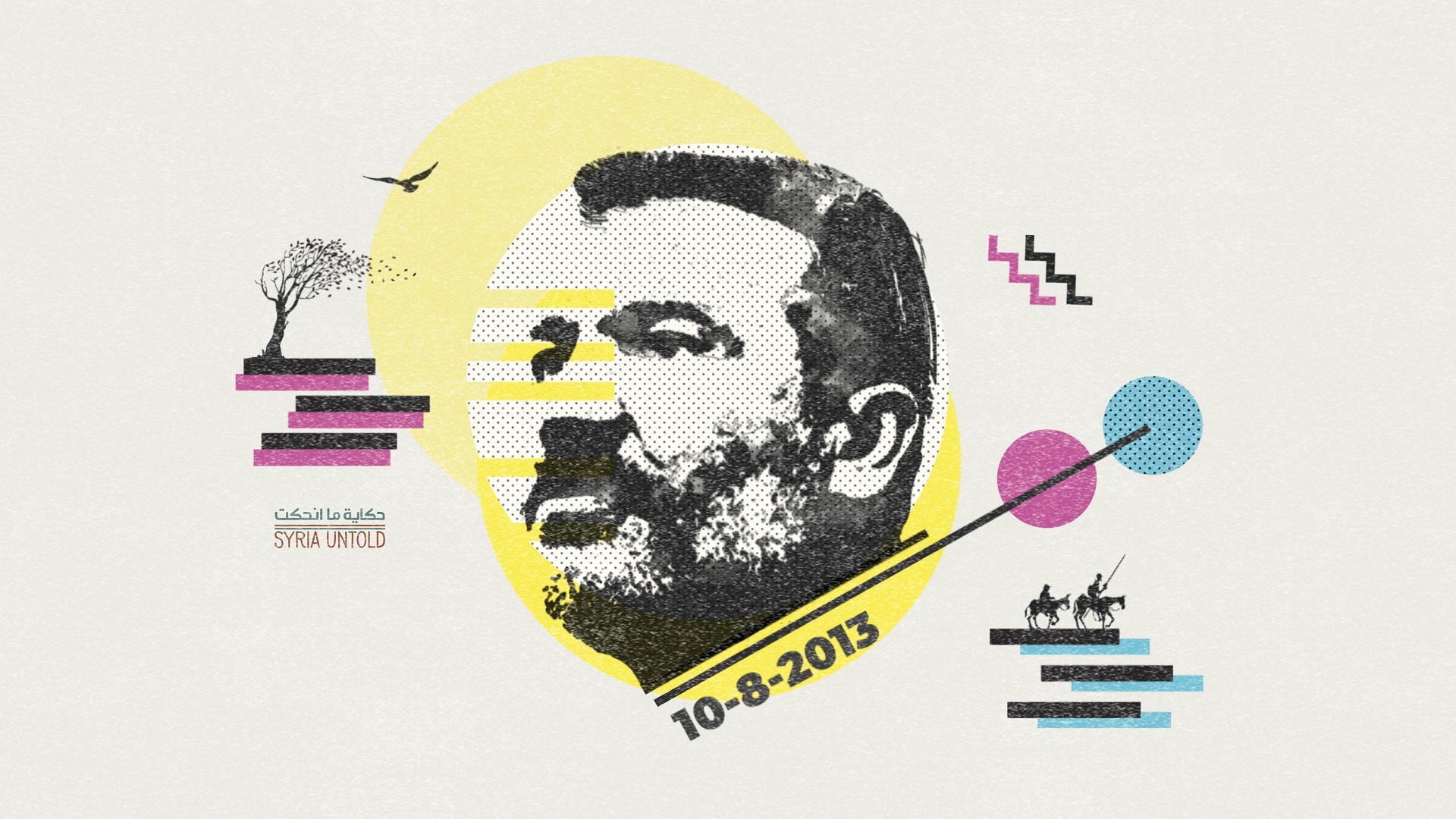

The above is an excerpt from former detainee Muhammad Sadiq Othman’s 2017 memoir Like a Resurrection. Othman was arrested in 2013, when he was just 17, and released a few months later. In this book, he remembers his life in prison.

Othman recalls his neighbors yearning to find out the fates of their own children after his release and return home. He recalls his longing for solitude and isolation.

Othman’s feelings are not unusual, as survivors of Syrian prisons have often experienced two states: they either need isolation from the outside world, or they feel the need to talk about their detention exorbitantly.

When prison guards finally released Abdulaziz Aldureid a couple years into the revolution, he was ecstatic. Now 31 and living in Spain, Aldureid recalls it as the best day of his life. “My favorite personal photo is the one taken of me on that day,” he tells SyriaUntold. Before his release, he had lost hope of freedom, but later on, he says he felt that a person could return to life after death.

His friends and family, who lived abroad, welcomed him like a hero—though, like Othman, he did not consider himself one.

“I changed my name on social media since I had been using pseudonyms. I put my real name instead, because it gave me positive energy. It was a sort of challenge to throw in the face of the regime. I wanted to say ‘Look, you arrested me, but you didn’t manage to kill my inner drive for freedom,’” Aldureid says. He began to see people differently. “Why didn’t they move a finger when I was being tortured close to them, just like thousands continue to be tortured? Perhaps if they had done something, this wouldn’t have happened,” he says.

Aldureid began to notice little details of daily life he hadn’t seen before prison. He appreciated that he had a nail clipper at home, which he didn’t have in prison. “I was harder on myself now. It was like I believed a person’s life can change any minute and he can endure harsh conditions and not have the things he takes for granted normally. In case detention or any similar experience recurs, I would be readier, even if slightly.”

Abir Farhoud’s family welcomed her after prison with pride and love, yet fear. They smuggled her out of the country just 10 days after her release on bail, and before she was scheduled to appear in court. She says her last 10 days in prison were the worst. Her release order had been issued, but she was kept in Adra prison for no logical reason. Prison authorities finally released Farhoud at night, along with another woman. They walked alone in the dark, close to the line of fire, where opposition forces were approaching the regime-controlled areas and heavy clashes were raging. The two women walked for hours before finding a taxi driver to take them home on the other side of the city.

Farhoud, now in her thirties, tells SyriaUntold and #ForJustice about the women she met after her arrest, including the story of a woman whom she stayed in touch with after leaving prison. The woman’s family locked her up at home after her release under the pretext of “fearing” for her safety. Her brother eventually freed her from the house.

According to Farhoud, Syrian society is often merciless with female detainees after their release from prison. “When I spoke about the sexual harassment that was part of the torture female detainees faced, people reacted with abusive comments and bullying, and people had a deeply negative outlook.”

Wassim Hassan’s story takes another turn. Now living in Germany, he remembers that after his own release from prison in 2011, his pro-opposition friends remained by his side for an entire week. But “the others who were against the revolution, including members of my family and people around me, strangely doubted me. They called me a traitor and an agent and treated me as if I were a criminal who wanted to sabotage the country. Some members of my extended family even posted on social media that I was a traitor and agent for Israel. These allegations had nothing to do with the freedom I dreamt of for my country and the dignity for its people.”

Hassan remembers experiencing strange, mixed feelings during that time. Even while detained, he was optimistic that Assad’s fall was imminent. “Still, I was cautious with the people around me, like my colleagues and neighbors. We exchanged strange gazes. It was as though they wanted to ask whether I was a friend or foe.”

He recalls the week after his release from prison, when he began feeling that he had to do or change something. He did not know exactly what, though. He painted the walls of his house with bright colors.

“It was strange, but I felt the need for colors after my release from that isolated cell underground, where everything was dark.”

In the 2009 film Long Night, directed by the late Hatem Ali and still banned in Syria, a political prisoner is released from prison after many long years.

On his way to his hometown outside Damascus, where his children await his arrival, the driver asks him about the route. He says that he does not know, but the driver retorts that the road has not changed. The former detainee answers that he no longer recognizes anything because he had been locked away for 20 years. He then asks about the old road, and the driver responds that he is familiar with it. “The old road has not changed,” he says.

The car stops, and the man steps out to stand under the rain. He feels raindrops caressing his face, like tears from the sky, for the first time since his disappearance into the abyss of detention.

He arrives at his village, to his childhood house, while his children look for him. Only his youngest son, who has walked in his father’s footsteps as an activist, senses where his father may be headed and follows him to that close, yet somehow remote village, away from the noise of the capital.

The man leans against an old tree, as though he wants to say, “Finally, I am home.” Then, he dies. His son arrives at the old house. He embraces his dead father and cries. Between his tears, he asks his father’s corpse, “Is that why you got out?”