A version of this article was first published in Arabic here.

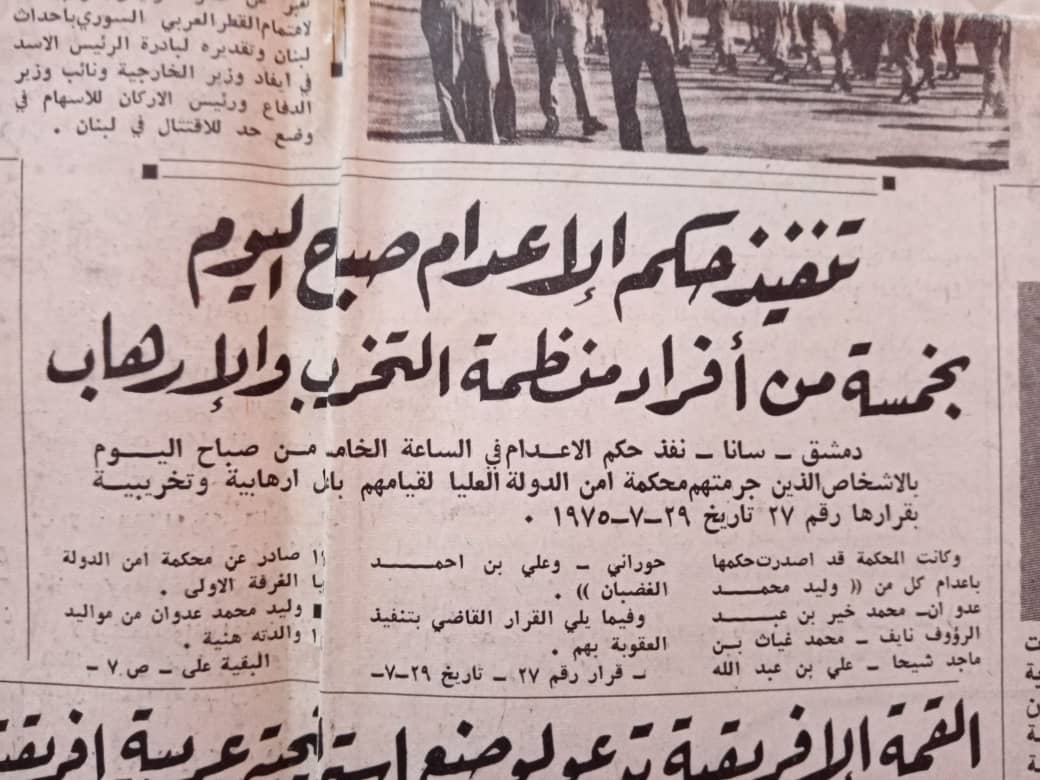

On Saturday, August 2, 1975, the Syrian government announced that it had executed five young members of a now little known communist organization. The five men, who included both Syrians and Palestinians, had been killed, most likely by hanging, in a secret location, away from the public eye.

Who were those men, and what did their deaths mean for Syria’s nascent Left?

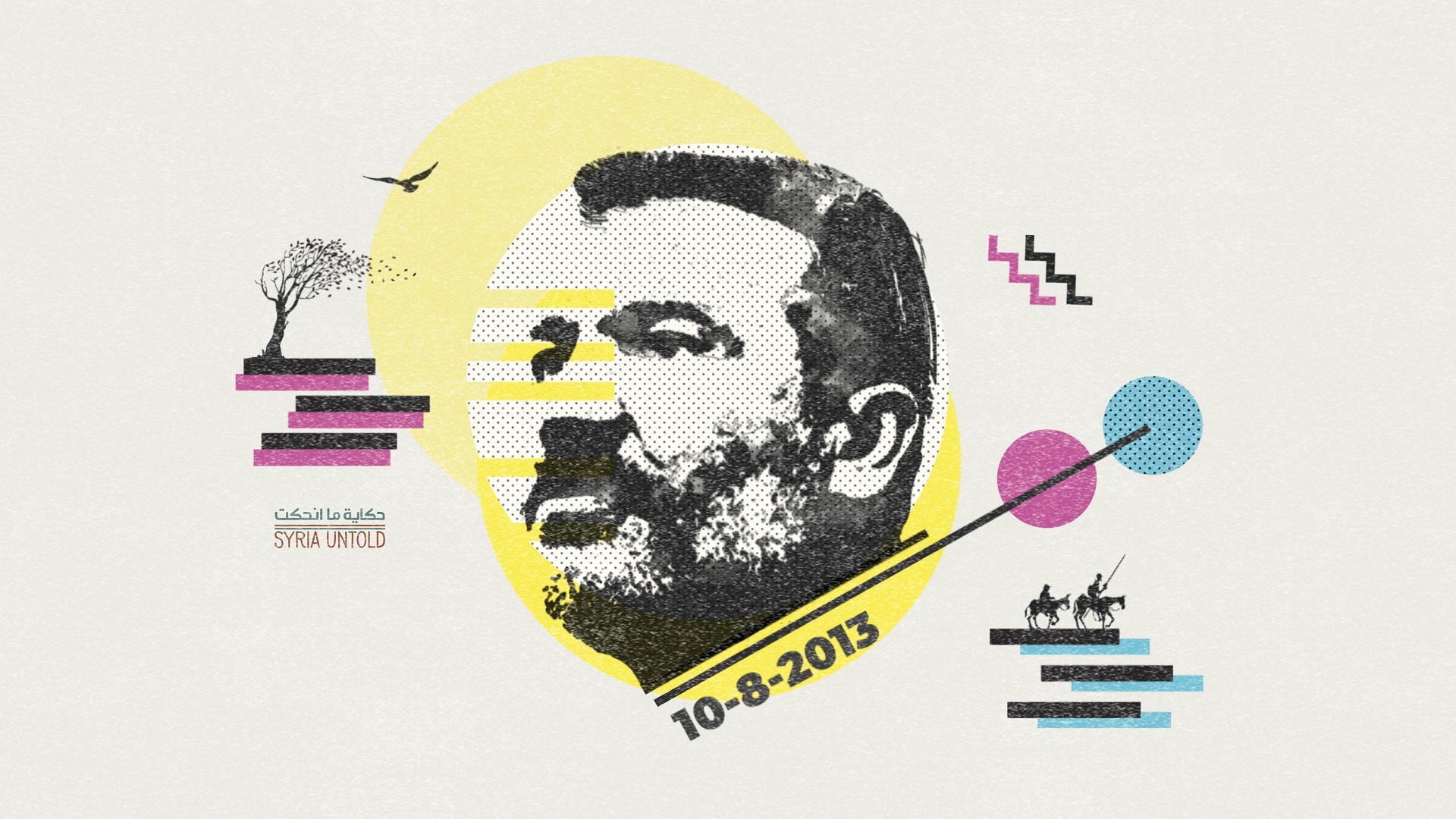

Syrian leftist writer and activist Wael Sawah wrote in 2018: “Most Syrians today do not remember the fighters of the Arab Communist Organization, but what they do know is the alluring painting by Youssef Abdelke titled Damascus, Saturday of Blood, which memorializes the day when five members of the group were executed. Perhaps Abdelke remembered the poem by Nazih Abu Afash about those men, titled ‘God is close to my heart’:

Syria’s Labor Communist Party, a rich political history

16 October 2020

Wael Sawah: 'I sacrificed literature for politics'

26 May 2021

Despair is close to my heart

My comrades hang naked like ropes of hemp

Five windows have shut

My sleep is a rose

Five bloodied headstones stand erect

Five lilies tousle the night air without reaching the ground

Peace is a rose

Five stakes remain in my heart

Peace to me

Peace to my country

Peace

To the millions of nests deserted in the heart

Peace to the rose”

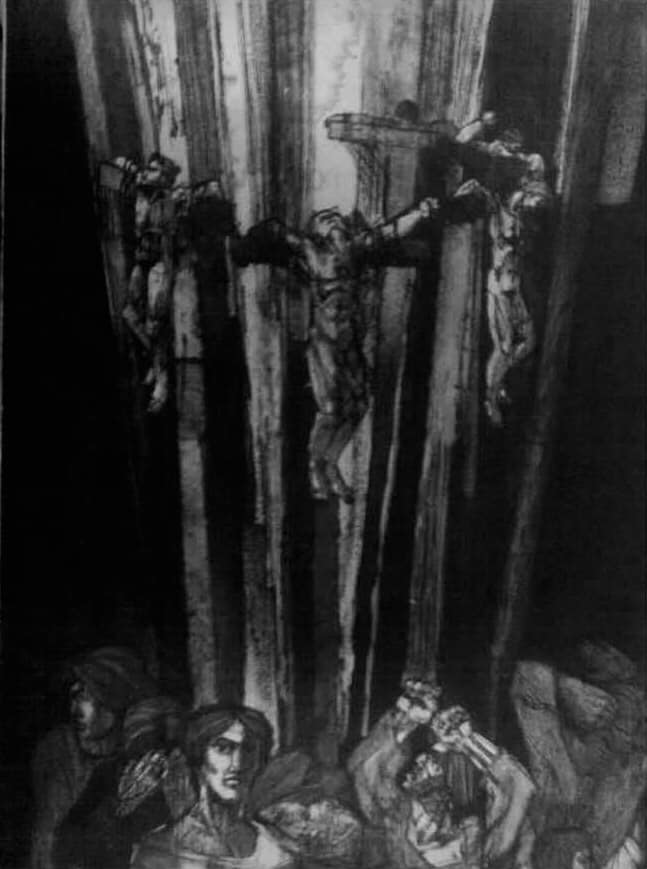

In Damascus, Saturday of Blood, five men hang “naked like ropes of hemp,” seemingly crucified, atop a bleak background of dark brushstrokes. Their faces turn upward.

The five men were executed in 1975 just as Syria was ushering in its period of political suppression, one that continues today. Known as the “kingdom of silence,” the first grim bookend of this era was drawn by Hafez al-Assad, who ordered the killings of many of his political opponents.

Those five executed men were Palestinians Ali al-Ghadban, Muhammad Kheir Nayyef, Ali al-Hourani and Muhammad Walid Adwan, and Syrian Muhammad Giath al-Din Majed Shiha.

According to Sawah’s telling of the executions: “At dawn on Saturday, August 2, 1975, five gallows were erected in the heart of Damascus, and yet the martyrs never made it to the site intended for their execution. At the last minute, the regime, fearing the consequences of a public execution, decided to carry out the crime somewhere underground. It refused to hand over the bodies to their loved ones, and the bodies remain buried in an unknown location.”

Within the margins, and breaking free: Syrian cinema

23 January 2021

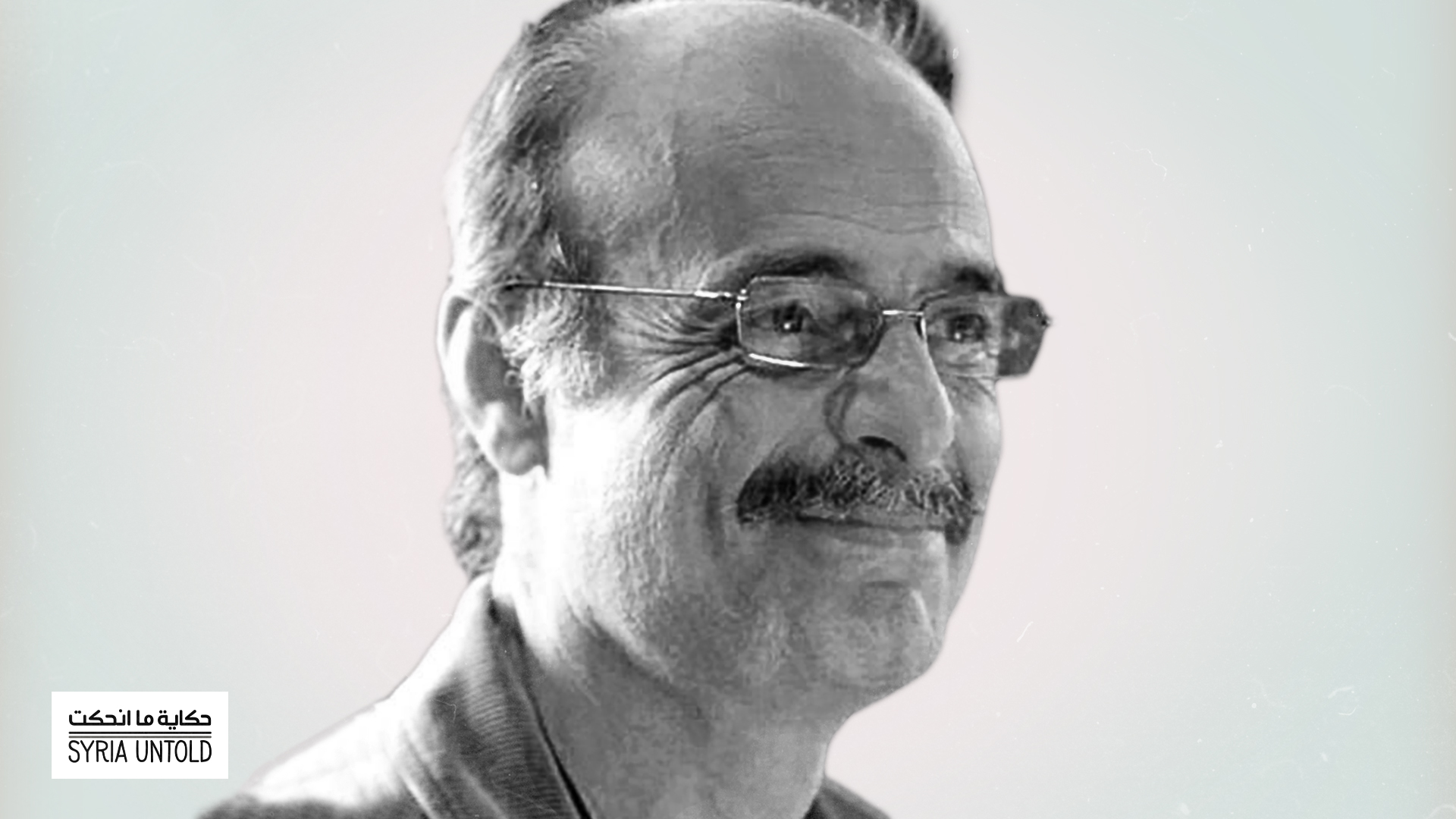

The killings sent “shockwaves” through Syria’s leftist circles,” Youssef Abdelke recalled recently to SyriaUntold. “I was in shock, so I produced a number of paintings, including Damascus, Saturday of Blood and Five Left and We Remain.”

Abdelke wasn't alone in turning to art after the killings. In the late 70s, Abdelke displayed the two paintings at the People’s Hall in Damascus. Throughout the exhibition period, the father of one of the executed men, Muhammad Giath al-Din Majed Shiha, was said to have visited daily. He remained silent, and kept to himself until the exhibition doors closed each evening, “as if visiting constantly would assure him that there were people who hadn’t yet forgotten his son.”

Other members of the Arab Communist Organization were also punished harshly starting in the 1970s. The 1975 executions of their friends only marked the beginning of their stories. Imprisoned for years and even decades, some of them became leftist “icons” for other political dissidents in Syria. Wael Sawah, who was detained in the same prison as them at one point, wrote:

“In Tadmur Prison, we glimpsed them from afar. We were never permitted to approach them, speak with them, wave to them or smile at them. They spent nearly 30 years moving from one prison to another, isolated from humanity, until finally they were transferred to Saydnaya Prison. Afterwards, they were released...The group didn’t leave behind a theoretical legacy, and it didn’t survive long enough to leave behind its own legacy of struggle, but its fighters became icons that lived in our hearts for a long time.”

What was the Arab Communist Organization?

The Arab Communist Organization was born at a time of emerging communist activity in Syria, Youssef Abdelke explained to SyriaUntold. “Since the early 70s, a new leftist, Marxist climate spread outside the Soviet Stalinist school. This included student movements in Europe and the emergence of new leftist political parties such as the Communist Action Organization in Lebanon, groups that forwent bargaining with states in favor of grassroots struggle.”

It is within this context that the Arab Communist Organization emerged, led by a small group of young, mostly male Syrians and Palestinians. Their names were:

From Ottoman Syria to Argentina

02 August 2021

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

Ali al-Ghadban (Palestinian)

Muhammad Giath al-Din Majed Shiha (Syrian - Damascus University)

Muhammad Walid Adwan (Palestinian - Faculty of Sciences, Damascus University)

Muhammad Kheir Nayyef (Palestinian - Faculty of Engineering, Damascus University)

Ali al-Hourani (Palestinian - Faculty of Engineering, Damascus University)

Hisham al-Baridi (Syrian - Faculty of Mathematics, Physics and Chemistry, Damascus University)

Muhammad Imad al-Din Majed Shiha (Syrian)

Muhammad Fares Murad (Palestinian)

Haitham al-Naal (Syrian)

Salti Nawwarah (Palestinian)

Bihth Kenaifati (Syrian)

Nabil Kenaifati (Syrian)

Mahmoud al-Abtah (Palestinian)

Jamila al-Batash (Palestinian)

According to Sawah, the group’s leader was Ali al-Ghadban, a charismatic young Palestinian with an ability to organize others around him. However, sources told SyriaUntold that leadership of the organization was collective, rather than in the hands of one member. In any case, wrote Sawah, “...they were convinced that change could only come through revolutionary violence. Their goal was to strike American interests in the region.” That included placing an explosive in the US’ pavilion at the Damascus International Fair, then another at the American company NCR’s headquarters in the heart of Damascus. Neither bomb actually caused any casualties.

Despite the two bombs they planted in Damascus, Arab Communist Organization members have long claimed that violence was not a primary goal of the group and that the explosives were aimed more at gathering attention than causing any real harm. Members also never announced an armed campaign or struggle when the group was still active.

Muhammad Imad Shiha, one former member, told Syrian activist Razan Zaitouneh in an interview shortly after being freed from 30 years of detention: “We never reached a stage in which we declared an armed struggle. Our activities were first and foremost political. The actions that we took against American interests took on the character of propaganda work; they were intended only as an echo of our political activities.”

Syria’s Labor Communist Party, a rich political history

30 October 2020

‘My photography is me’

17 August 2021

Wael Sawah wrote about Muhammad Fares Murad, another member of the Arab Communist Organization:

“When I met Fares Murad, after the 27 summers he spent in regime prisons, he seemed to me like a normal human, his back hunched over as if he had been bent in half. And yet, his mental, political and moral tenacity made him tough. In his house in al-Fahhamah, Damascus, he told me: ‘Armed work in itself was not a goal. It was a way for our voice to be heard because we had no other option. The basis of our militant action was just to raise media attention, and not to target people at all.’”

However, during one operation, Arab Communist Organization members did kill a guard, albeit unintentionally, according to Shiha in his 2004 interview with Razan Zaitouneh. “As I said, the actions we carried out were of a propagandistic nature. We took care not to kill anyone. However, one civilian was martyred once, a building guard, as a result of one of our operations, despite taking the utmost precautions to avoid something like that.” He added: “Current conditions in the world don’t allow for the use of armed operations as a tool of resistance...Now there are other ways to struggle for justice and freedom.”

According to Sawah, “Fares, Imad and the others had to live with the killing of that nighttime guard for 30 years...It is very clear that this guard disturbed the consciences of members who are still alive, and that [his death] was not a goal.”

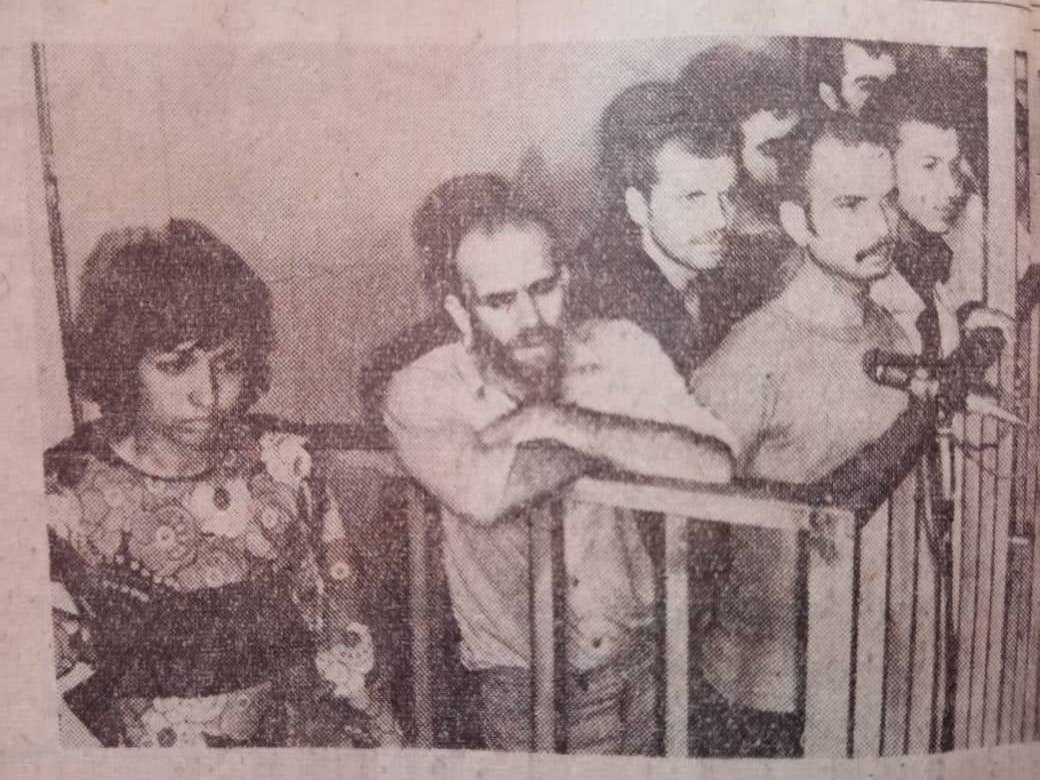

Dismantling

These operations, as well as the group’s threats to American and Western interests in the Middle East, prompted various regional intelligence agencies to suppress members of the organization with “unparalleled ferocity,” according to Sawah. One branch of members was said to have been arrested in Lebanon, with the help of a Palestinian faction loyal to the Syrian regime. Among the arrestees was prominent member Ali al-Ghadban. Officials also raided the home of Muhammad Shoqair, “who was later tortured to death, and who, in his final moments, confessed against his comrades, all of whom were arrested within hours. Their sentences were issued as quickly as possible, after a sham trial in the State Security Court.”

Other sources told SyriaUntold that all of the organization members who were arrested were detained in Damascus, not Lebanon. Their sentences were said to have been as follows:

Ali al-Ghadban: execution by hanging

Muhammad Giath al-Din Majed Shiha: execution by hanging

Muhammad Walid Adwan: execution by hanging

Muhammad Kheir Nayyef: execution by hanging

Ali al-Hourani: execution by hanging

Hisham al-Baridi, Muhammad Imad al-Din Majed Shiha, Muhammad Fares Murad, Haitham al-Naal were sentenced to life imprisonment and Salti Nawwarah, Bihth Kanaifati, Nabil Kanaifati, Mahmoud al-Abtah and Jamila al-Batash were sentenced to 15 years in prison.

Though the organization went silent after the crackdown, its story didn’t end in 1975. Those who were sentenced to 15 years behind bars served their time and then were released. The others weren’t so lucky, going on to spend three decades in Syria’s dark network of prisons.

The last of them, Muhammad Imad Shiha, who was arrested on June 21, 1974, was finally freed more than 30 years later, in August 2004. He walked out of prison into the still relatively new Syria of Bashar al-Assad, who had succeeded Hafez only four years earlier. The years to come would prove that Syria under Bashar was no less brutal than the Syria that had first detained Shiha and executed his friends and brother three decades before.