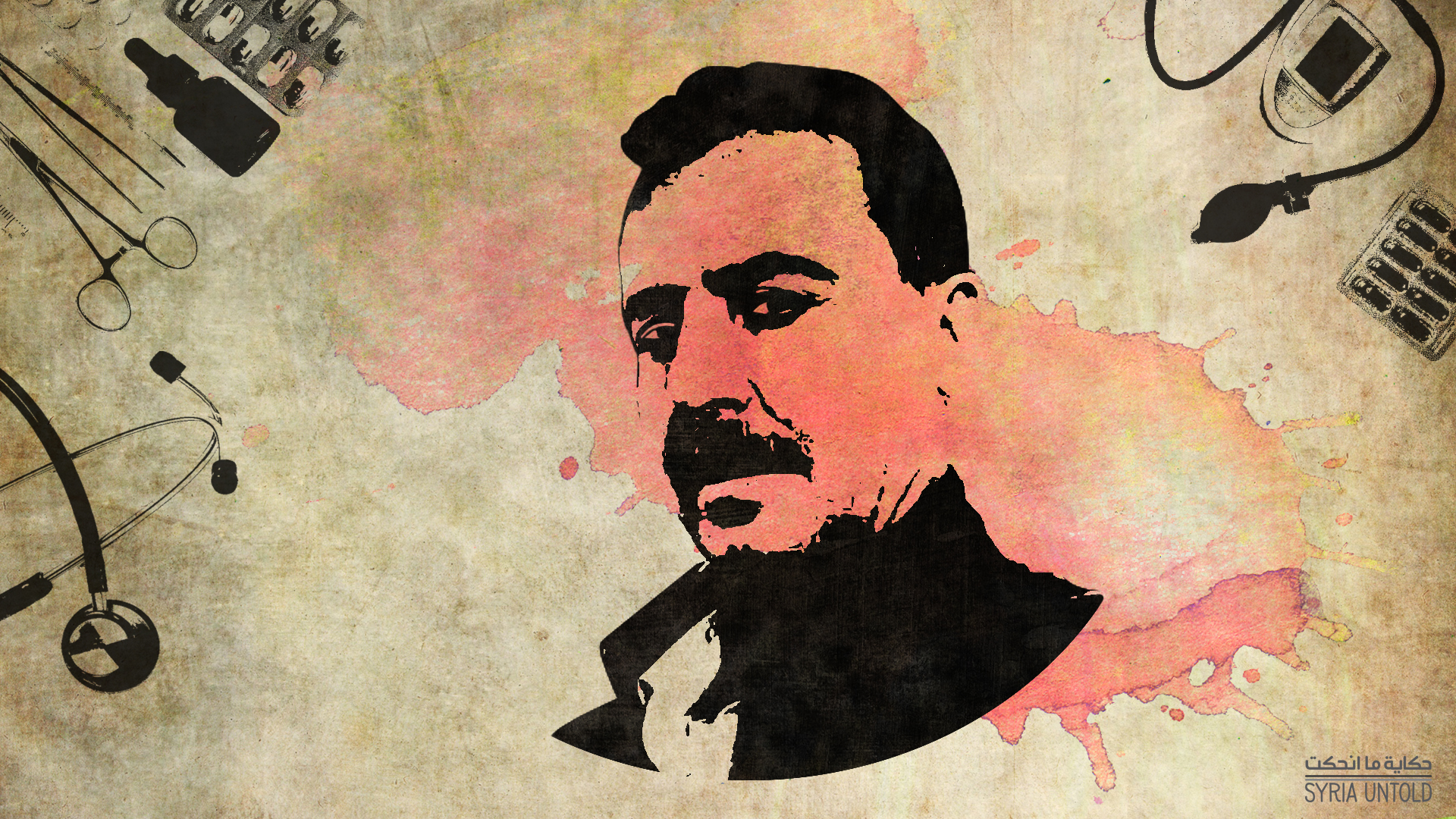

SyriaUntold recently spoke at length with political dissident Rateb Shabo, known since the 1980s as a figure within the Syrian Left. He discussed exile, the state of Syrian leftist politics and long years stretched out within prison.

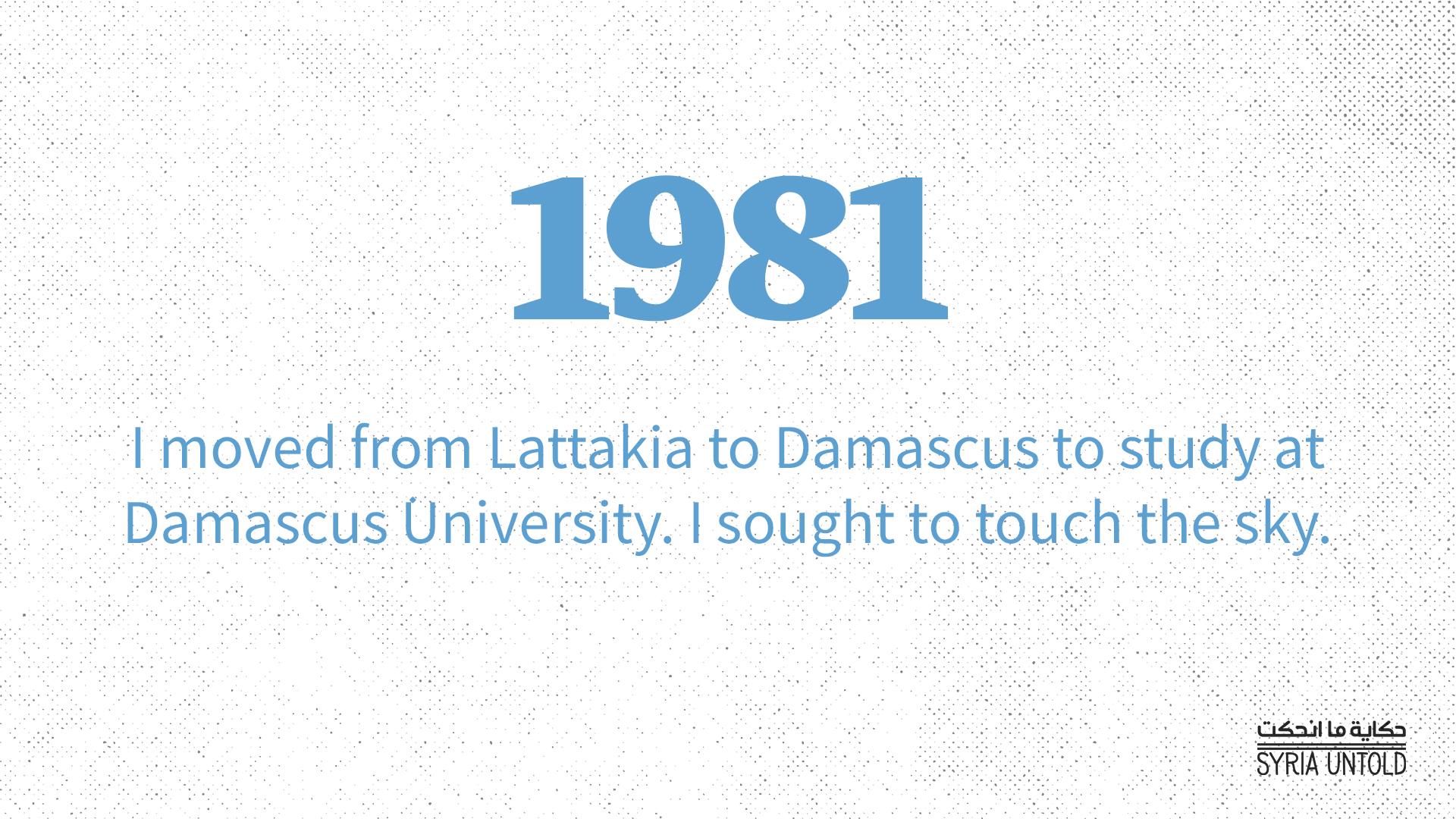

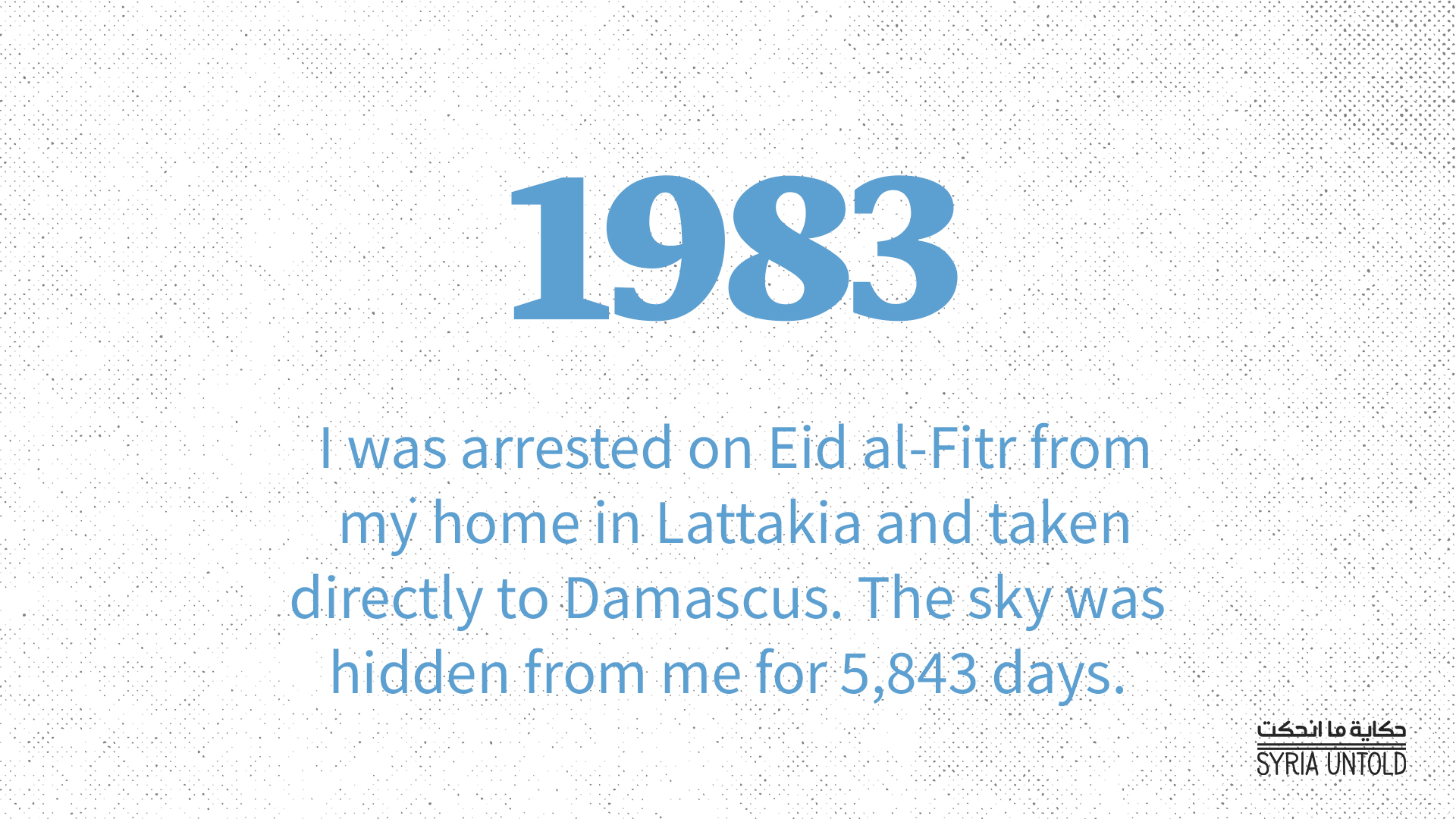

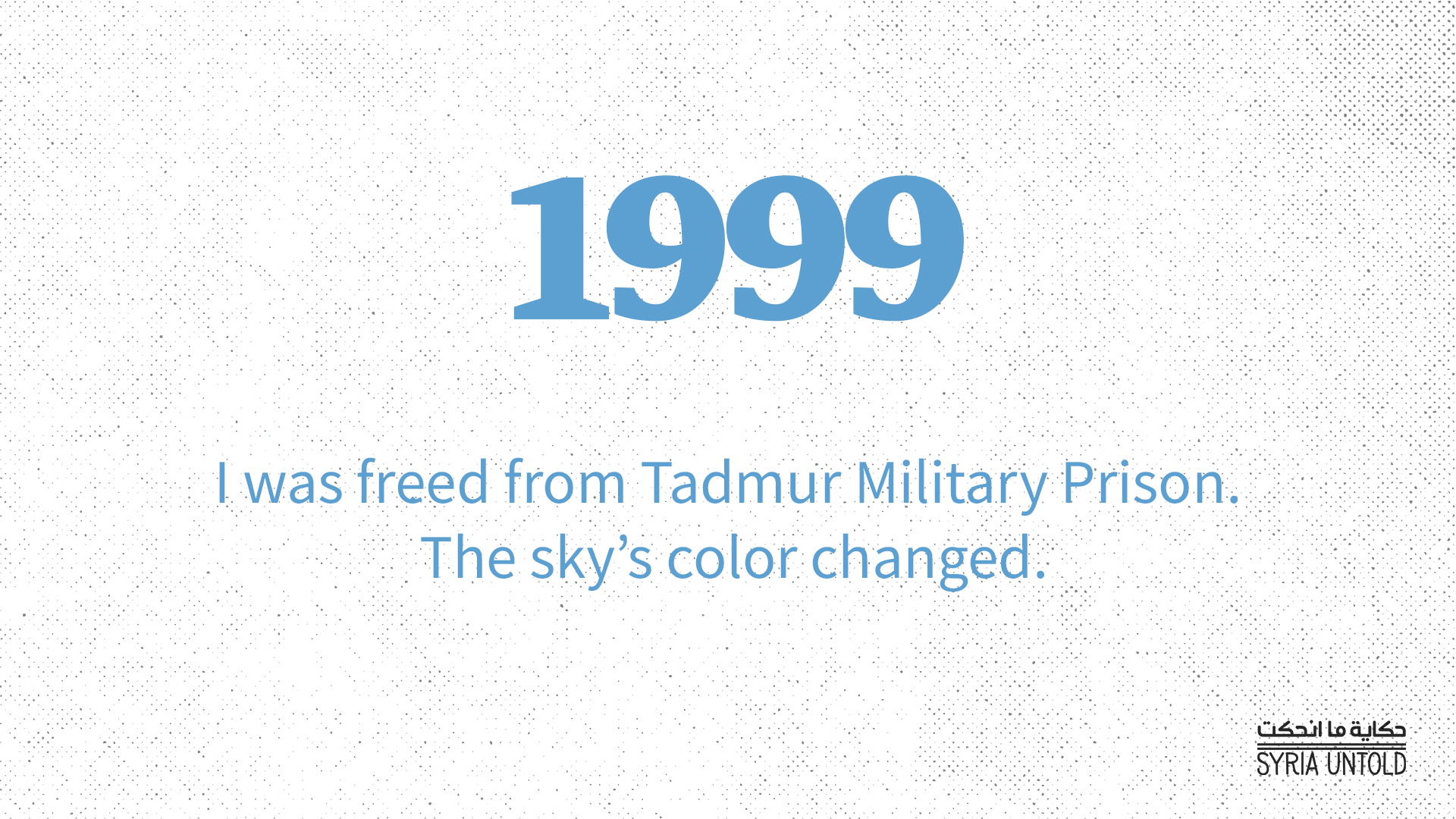

His latest book, reviewed here by Joseph Daher for SyriaUntold, was published in 2020 and follows the story of Syria’s now-defunct Labor Communist Party. Himself a former member, Shabo was arrested in 1983 for his involvement in the party. He was a young medical student at the time, born into an Alawite family from the Syrian coast. Shabo spent the next 16 years as a political prisoner, including at the notorious Tadmur Prison in the eastern Syrian desert.

Shabo now lives in exile with his family in Lille, France, where he works as a writer. One of his recent books, What is Behind These Walls, documents his years in Syrian prison.

“Exile is easier for those who have experienced prison,” Shabo says of life cut off from Syria. Still, he says, the maqam, or rhythm, of life away from home is difficult to bear. It is “heavy, sad and painful.”

“It is a Syrian maqam.”

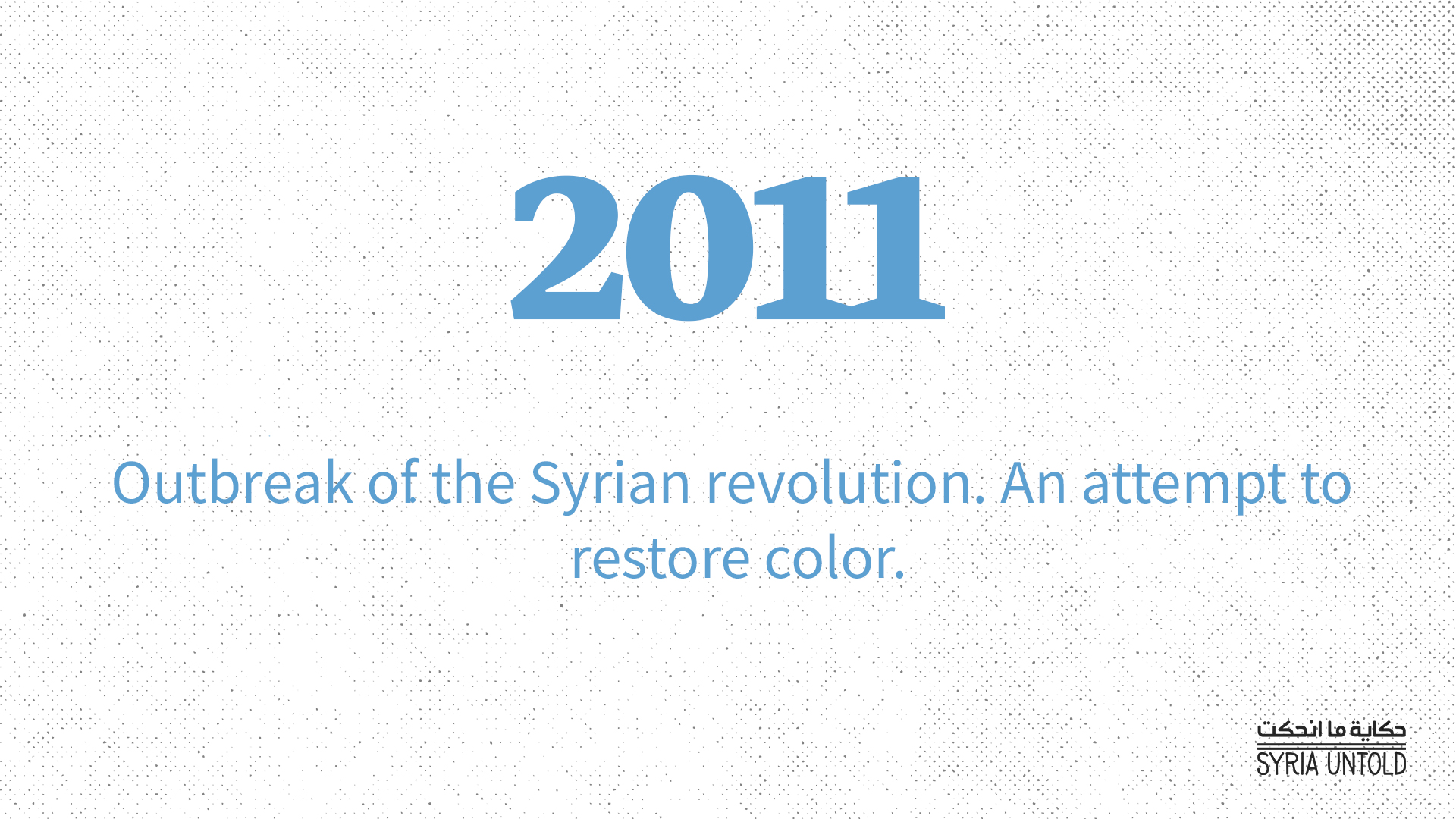

Milestones in Shabo's life:

People who are familiar with your writing, imprisonment and exile often know little else about you. Can you talk a bit about your life in France since leaving Syria?

For the past seven years, my days have taken on a steady rhythm, interrupted only by emergencies and a little bit of travel. The beats of that rhythm are a glass of coffee, then a walk in the public park. Then I work in my modest home office, which my family calls the “hermitage.” After that, I take an evening walk. Atop this steady rhythm, the melody often changes, but the maqam, which is heavy, sad and painful, does not. It is a Syrian maqam.

I walk in a public garden, which the municipality tends to as if it were someone’s home garden. It has flowerbeds, a petanque court, green spaces, poplars, sycamore trees, and other types of trees I don’t know the names of. There are very tall trees that line the walkways, trimmed into geometric shapes. This hurts me and angers me—why can’t we be like this? Why do they create all this beauty in their countries while our countries sow only fear and corruption?

Syria’s Labor Communist Party, a rich political history

16 October 2020

Hala Abdullah: 'I believe in cinema as a means of resistance’

11 June 2021

I love reading poetry and novels, but mainly I’m reading non-fiction books these days, reference texts and studies that help with my writing. Of course, I also read news about Syria and the world.

I have little contact with my friends, but I miss them greatly, especially my friends from prison. In late 2019, I thought of meeting up with all my prison friends so we could spend a few days together. I found a house and got in touch with a few of them, but the COVID-19 pandemic put a stop to the gathering.

You spent 16 years in various Syrian prisons and wrote about this experience in your book What is Behind These Walls. Can you talk about how your family handled your imprisonment, especially as you come from the Syrian coast, an area often seen as a backbone of regime support?

When I was arrested in 1983, political polarization was not as intense as it became after 2011. The general public at the time did not see political opponents of the Assad regime as “traitors” or “agents.” It was a very different picture.

My family’s stance towards my opposition to the regime was not negative. Rather, they appreciated my position, and that of others (except for the Islamists, of course) against a regime of coercion, corruption and discrimination, none of which was ever hidden from them. At the same time, most of my family remained convinced that this confrontation of mine would fail, that the only people who would pay the price would be my relatives and me.

At the time, the modus operandi for most people was to ignore the fact of my imprisonment. My mother always greatly appreciated any person who would break that facade and ask her, even if it was just a question, about how I was holding up in prison. For my part, like my prison mates, I was happy whenever I heard from my visitors that someone outside had asked after me. This was the case for all of us. We had been tossed away like worthless garbage, gathering the dust of oblivion. This led some of us to lose our belief in society, as it was a partner in the crime of our imprisonment. In general, society had died. There was a humiliating acceptance of defeat before authority. It is no surprise that one of the first cries of the Syrian revolution in 2011 was “The Syrian people will not be humiliated!”

It is impossible to talk about a “Syrian Left” today. We can talk about scattered groups that are weak in relation to Syrian society

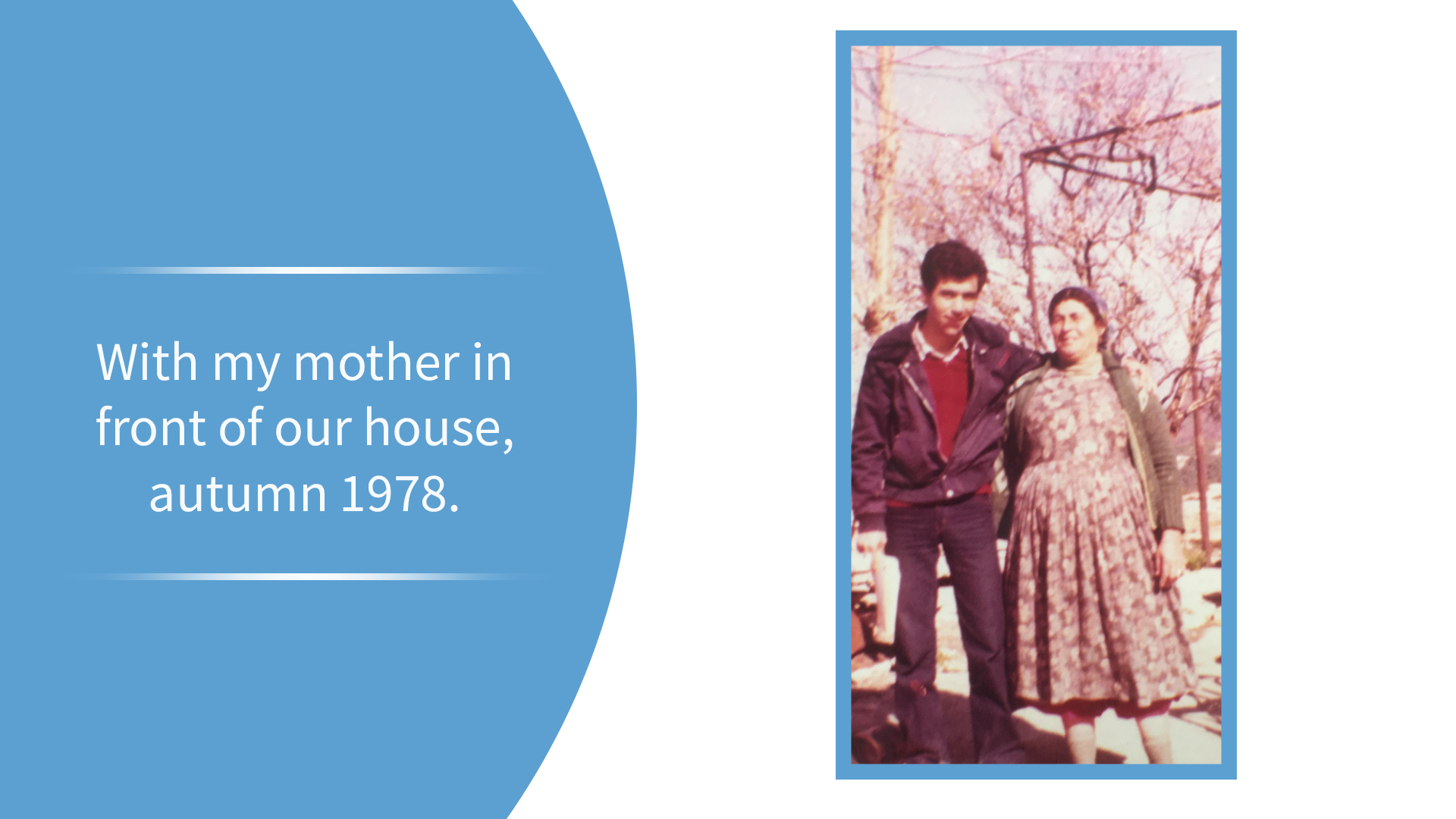

In order for a family to continue its life, it must grow accustomed to the prisoner’s absence. The mother is the least prepared for this. Amid so much silence, my mother would keep placing my picture at shrines to remember me, even after my father became tired of her constant complaints.

After 2011, there was a deep-seated change in the Alawite sect. Dissidents were no longer accepted, even within their own families. This even applied to families who had long histories of opposition to the regime. They paid heavy prices for the political stances of their children.

Wael Sawah: 'I sacrificed literature for politics'

26 May 2021

You published a book last year that chronicles the story of Syria’s Labor Communist Party. The book filled a serious gap in writing on the topic. As a leading former member of the party (and correct us on this if we’re wrong), can you talk about why it rarely published its own writing on itself? Why did it stick to secret publications that only a few diligent researchers have access to? Why did you wait so long to write a book like this?

I wasn’t a leader at any level of the Labor Communist Party. When the head of the Political Security branch in Damascus interrogated me as part of an arrest campaign [in 1983] against 14 students from Damascus University, he classified me as the “student organizing officer at Damascus University” in order to make himself seem valuable to his superiors. That way, he could claim that he had detained “big leaders,” rather than just students who weren’t politically active, some of whom hadn’t even heard of the party before. Because of this classification, I spent twice as long in prison as my colleagues.

I can say that I was enamored more by the experience than the party itself. What attracted me to the party was its opposition to the regime, its struggle, its loud words in the face of power, its contact with those active and hard-working young people who believed in an idea and would remain loyal to it until death. All of this attracted me more than the correctness of the ideas, its policies and its political analysis. I had no immune system against what this party was saying. Indeed, this is a youthful danger that is difficult to treat, and is perhaps the basis for the strength of jihadist Islamist organizations.

Naturally, the party “writes” its history through its activities, writings and political stances. The Labor Communist Party was quite active and prolific compared to other opposition parties. Its activities were secret, but it is not correct to say that its publications were secret. On the contrary, like other opposition parties that faced severe and continued repression, it sought to make its publications known and spread them to as many people as possible. That said, the party’s limited capabilities and a lack of popular interest hindered its reach.

A party cannot write down its own history. And if it does, it writes from a place of propaganda and boasting that certain events prove the correctness of its political stance. The only history that can be trusted on any party is that which is written from outside the party, free from bias and partisan beliefs.

All Syrians have become strangers to their homeland. Or, perhaps, exile itself has become their homeland.

Yes, I was late to writing the history of the Labor Communist Party. This is strange really, as many former members went on to become writers and researchers. You’d think that writing the party’s history would be a priority. Without a doubt, there are useful and capable testimonies, such as that of Wael Sawah, and fantastic analysis articles, such as those by Ali al-Kurdi—both of whom were party leaders. This is not to mention the numerous yet inaccessible or subjective writings about the party.

I’m happy to be the first to write the story of the party, something that took a lot of research and time. Obtaining the party’s archive was itself a challenge, as it was lost in the arrest campaigns. To get a more complete archive of the party, I had to visit the International Institute of Social History (IISH) in Amsterdam.

In any case, I wrote the history of the party from a researcher’s perspective, and not as a “son of the party.” And I know that there is more than one writer working on recording this rich history.

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

Today the Syrian Left faces stark polarization. What is the Syrian Left today anyway? Why is there an effort by some to monopolize the Left? And does the Syrian Left still have a place in today’s landscape?

Very broadly speaking, the Syrian Left can be defined as the non-Islamist forces at play outside the ruling party. This Left was polarized after 1970 because it never had enough power to be independent. It is gambling with both the regime and the Islamists. I can say that the most notable attempt by the Left to gain real independence from both extremes of Syrian society (the authority and the Islamists), regardless of the correctness or incorrectness of its political stance, was that of the Labor Communist Party, which was shattered by successive waves of suppression.

The Syrian Left always lived in a violent environment, which is a permanent feature of the political sphere in our societies. Politics disappears amid violence. It disappears and transforms into subordination, and whoever rejects subordination ends up crushed unless they have the strength to crush or at least fend off others. The Syrian Left has never had this strength. The same applies to the Right (the Islamists), but the latter have had the preparedness and capabilities to possess power and confront the regime’s violence, as well as co-opt some of the Left.

Throughout its history, the Syrian Left has been in a subordinate position and has not itself possessed much power.

Indeed, it is impossible to talk about a “Syrian Left” today. We can talk about scattered groups that are weak in relation to Syrian society and that may serve, in light of the current situation, as merely a front turned outward for support.

There are transformations, questions and new cases that put our understanding of both the Left and the Right in the lurch. The one constant in what we can call “the Left” is a bias towards the idea of justice and equality. The distinguishing element in defining the Left today is the global dimension of equality, or “internationalism”—not in the sense of Soviet alignment, but rather in the sense of unity and resistance to the closed-minded nationalist tendency that has emerged in wealthy countries to justify their lack of solidarity with poor countries. This same tendency also appears in poor countries to justify tyranny.

Very broadly speaking, the Syrian Left can be defined as the non-Islamist forces at play outside the ruling party.

The new aspect that arose on the international stage following the collapse of the Eastern Bloc was the disappearance of the false polarization between East and West, or between communism and capitalism, and the exposure of the constraints of national democracies. We can see these limitations clearly in global issues like the climate crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, both of which revealed the extent of “national” selfishness and the need for equality on the global level.

Damascus’ forgotten ‘Saturday of blood’

07 September 2021

‘Recreating a beautiful thing’

27 August 2021

You spent the better part of two decades in prison, and have now lived in exile for the past several years. How do you see exile, in light of your experience as a former detainee? Do you see exile as its own form of imprisonment?

The word “exile” has been associated in our minds with individual cases, often affecting influential individuals who are neither arrested nor killed by the authorities. These authorities nevertheless want to get rid of their internal influence by banishing them from the country. This meaning of exile does not apply to Syrians. We escaped from killing, kidnapping and arrest. There was a mass exodus from areas that faced bombing, or those that were awaiting that same fate. People left in search of protection from death, wherever that was, and however they could get there. We can call this refuge, yet it conceals the fact that such exile cuts off the exiled from justice.

Massive changes in the field of communications have changed the repressive nature of exile. It has become possible for someone to be active and influential in their society from abroad. Distance from one’s country no longer suffices to “exile” the influence of a person who has the capability to influence.

In light of the poor conditions Syrians live under inside Syria, exile has become a privilege.

Given the general state of exile that Syria is witnessing—millions of Syrians have sought refuge abroad, millions of others have been internally displaced and millions are living below the poverty line to the benefit of a narrow group of Syrians—it is more accurate to say instead that Syria itself has been exiled. All Syrians have become strangers to their homeland. Or, perhaps, exile itself has become their homeland.

As for the comparison between exile and imprisonment, imprisonment is much more difficult. In prison, not only are you deprived of your freedom, but you are also at the mercy of the warden. You are directly dependent on him for your biological existence, for your food and water. You are under his watch, his moods, his punishments. You feel no stability in your dignity or in your safety. In exile, you are deprived of your spatial and social environment (this deprivation is achieved by prison as well) but you are free from your jailer. You feel safe, that your dignity is more protected. Exile is easier for those who have experienced prison.

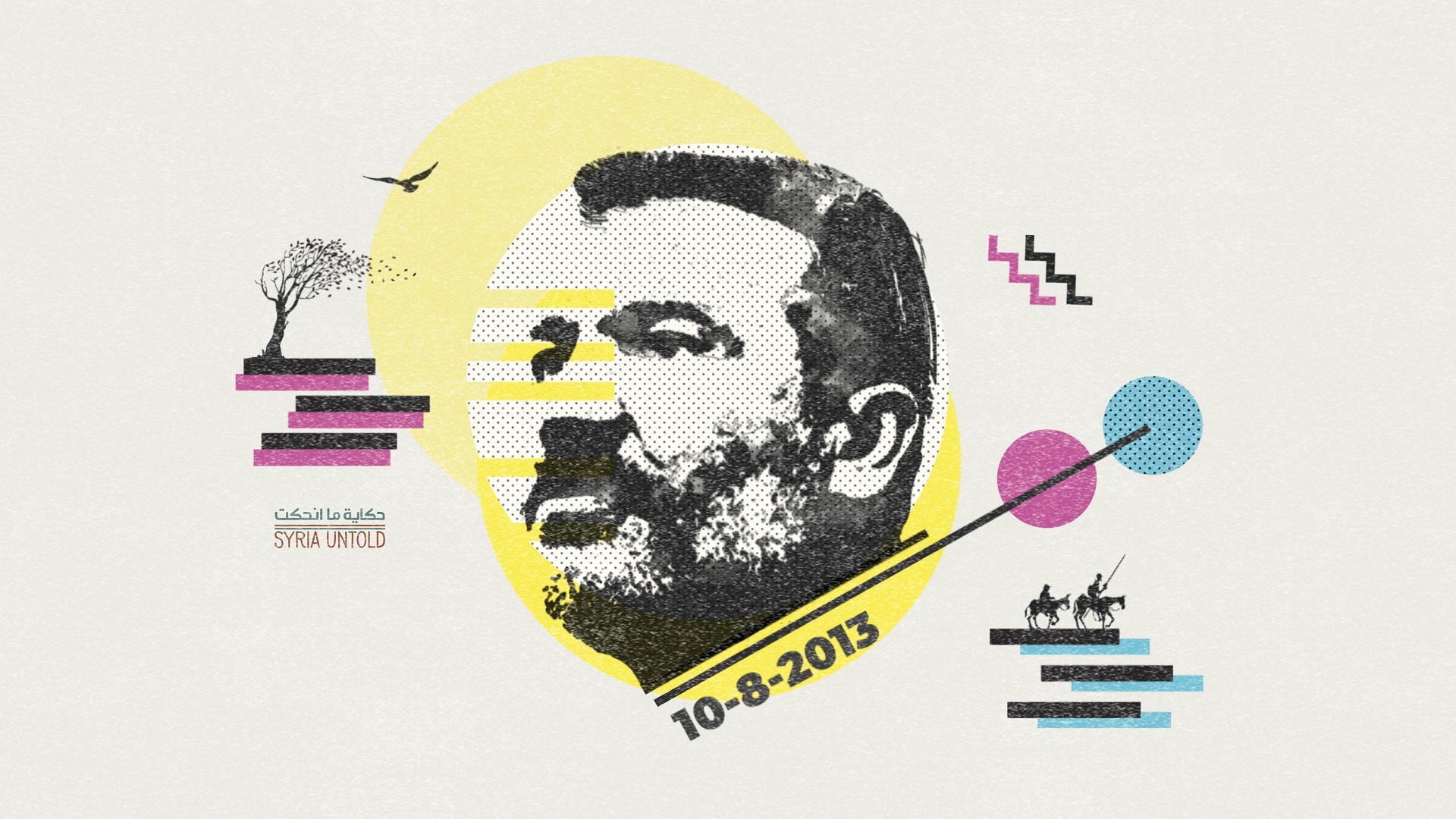

Friends and colleagues speak about Rateb Shabo

I first met Rateb in Damascus, in winter 1981, the year he entered the medical college. He was a young man. You could immediately notice his intelligence, his quick wit and his ability to organize his thoughts and opinions. He also had a sarcastic side. My friendship with our colleagues and with Rateb’s relatives, such as Jamal Saeed and Bahjat Shabo helped me become fast friends with Rateb. But later I was forced to go into hiding and leave my house. That was followed by Rateb’s arrest and his transfer to Adra Prison. News came to me from him only sporadically, when he started writing with a group of prison mates. Their writing was smuggled out of prison and published in the al-Tariq magazine (a Lebanese communist magazine). These were his first steps towards journalism, albeit with a pseudonym and alongside a group of other writers.

Rateb Shabo is one of the names that remained solid and retained its value and morals despite his long imprisonment and his transfer between Adra and Tadmur. He did not give up on his eventual release and freedom. After he was freed from Tadmur Prison and moved back to Lattakia, we met rarely, as I was living in Damascus.

When I met him again after some time, I asked him: “Why don’t you write for the newspaper? You have both a pen and ideas—who else has both of these gifts?” He replied that he was very busy. Despite his delay in entering the field, he quickly became a well known and brilliant name.

July 1992: Summer was in its glory, and the minibus that was headed toward al-Wafideen Camp and Adra Prison was packed with the familiar faces of prisoners’ families and their children. We sat on a little side bench to make room for the elderly passengers, while the aisles and spaces beneath the seats were crammed with threadbare bags. It was one of the Mondays set aside for visits, and I’d been sneaking out to visit friends.

Remembering my friend Bassel Shahadeh

28 May 2021

A forced disappearance in Raqqa, and the empty spaces left behind

09 December 2020

That month is stuck in my head like that memory. Those eyes are still looking towards me from two gates away, filled with the same enthusiasm, as I look towards them with the same curiosity and longing. The walls were about a meter and a half high, built gradually in the form of square rooms, topped metal gates that reached the ceiling. The wiring of the gates disappeared little by little as the prisoners entered the hallway to take their places in the corners of these rooms, to meet the visitors.

I knew most of them by name, names that we could sum up in one word: the “guys.” They were my relatives, my friends, and cellmates who once brought us together when we spent time in the basements of one of the security branches. And then there was the stubborn face of the tall, thin young man; all he had to say was that he was from the coastal mountains. That was Rateb, with his laugh, his acerbic humor that his prison term (by then it had been nearly a decade) could not diminish.

That day, the stories I had heard from colleagues who had been released from prison became humans, eyes, laughter, chatter. And Rateb became that friend with the Cancer horoscope, who responded to my birthday greetings by sending me the gift of one earing made of a bead, written across with the message “with one ear”; you had to look out for his sarcasm and always be prepared for it!

In the following years, and during my rare visits to Adra Prison (which was a five-star hotel compared to Tadmur, Saydnaya and the security branches) the “guys” were always prepared with lists of books they wanted from us. They were ready for visits from friends and evenings with colleagues and family members. There was the smile of Umm Fadi, which I cannot forget, as she was preparing to visit Adra prison with all the love she could muster for her son and his friends.

Then came the disaster. As a disciplinary measure, they were transferred, all of them, to Tadmur Prison for many years. Rateb remained determined, and for many years all we heard of them were distant stories of desert dust and the cruelty they experienced.

December 2000: Winter was nice this year, and Lattakia welcomed many loved ones. They came home after long absences, their bodies thin to the point of breaking in two, their faces pale. And yet their eyes still radiated intelligence and determination. Something broke in the city’s atmosphere and overshadowed the joy-filled with tears, the stories that had been imbued with hidden secrets for years.

Personally, I didn’t dare ask any questions. It was enough for them to say what they had gone through, what made them reach that level of pallor. The only joy was that they had finally escaped from the slaughterhouse.

All I know about Rateb are little flashes of memory: he returned to university, he became a doctor, he opened a clinic, he married a beautiful and kind woman, he had children, he told us stories of women seeking beauty in the plastic surgeries he performed. He retreated from writing for years in order to work and re-establish his life, to get back all that he missed out on.

Then he left Syria and returned to what he loved and what he was good at. There was his passion for research, for following current events and writing with a sharp pen. He stirred up controversy and debate, watching everything that was going on. He is still that stubborn, acerbic young man.