This article is part of our series on Arab photography funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, with guest editor Muzaffar Salman.

Read this article in Arabic here.

“I believe on such an issue as this no one is or can be completely truthful. It is difficult to be certain about anything except what you have seen with your own eyes, and consciously or unconsciously everyone writes as a partisan. In case I have not said this somewhere earlier in the book I will say it now: beware of my partisanship, my mistakes of fact and the distortion inevitably caused by my having seen only one corner of events.”

- George Orwell, Homage to Catalonia, 1938

I was walking in the Pyrenees Mountains that stretch along the natural Spanish-French border. Just as I was about to enter the tiny dusty road of a Catalan village called La Vajol, I saw someone wearing a helmet, slowly riding his motorbike towards me. The first question that you ask yourself when you are a stranger in a remote place is whether the people there will recognize you as a foreigner. Of course, the insecurity of wearing stinky clothes, a dirty backpack and a cheap plastic analog camera like mine were what announced my own foreignness.

“Hola, de dónde eres?” he asked me. Where are you from?

In search of the best picture in the world

22 January 2021

Children at war: Reliving photos of east Aleppo

25 September 2020

For me, the answer is never simple and probably will oblige me to explain many things associated with the place I come from. On top of that, I don’t understand the necessity to know where someone comes from, or what nationality and identity would add to the conversation.

Maybe it is the natural attitude of belongingness, or it is our human need to be an accepted member of a group. To belong or not to belong is a very subjective experience. It is imbued with our inner selves as well as our surroundings.

The problem with belonging is the very idea of being categorized within a certain identity without any choice to refute that label. For instance, things like xenophobia, authoritarian states, war and refugee crises are hidden labels that force themselves onto you when you answer “where are you from?” An answer like “Syria” (where I come from) carries invisible identifications that, however involuntarily, embody themselves within those of us who belong to that place.

Belonging and non-belonging make themselves known on many other scales. For example, international news agencies segregate “East” and “West.” They publish photographs of the bloody corpse of someone killed in a conflict in the Middle East, Afghanistan and Africa. However, those same news agencies obscure the bodies of those killed by, for instance, a terrorist attack in Europe. The issue is not the instrument, which is photography here. No, it is the structure and the entity that can decide representation according to certain propaganda ideals, regardless of what media consumers actually want or need.

When someone calls themself a photographer, a painter or a writer, or if others around them do, then it means that person belongs to the category of photographers, painters and writers. If this person then changes their aesthetic or artistic framework, sometimes others will not accept this new perspective. The person will be judged for stepping into another territory of belonging, rather than for the quality or the craftsmanship of their new endeavors.

The problem with belonging is the very idea of being categorized within a certain identity without any choice to refute that label.

Because belonging is so subjective, nomadism became my own way to survive. I wandered the borders between France and Spain, enjoying my freedom from both time and space, and even from any one specific aesthetic. At one point, I encountered George Orwell’s memoir Homage to Catalonia, which details his time as an anti-fascist militant during the Spanish Civil War. His personal experiences and observations with the Republican rebels made me contemplate the intersections between the Syrian revolution and the Spanish Civil War.

Though Orwell was considered a foreign volunteer in the war, he had a deep understanding of the Spanish conflict. Not just because he fought with the POUM (Workers' Party of Marxist Unification) militia, but because of his daily interaction with every detail, starting with his first impression when he arrived in Barcelona and ending up on the front line of Aragon.

A decade on, how can we work to free Syria’s detainees?

16 April 2021

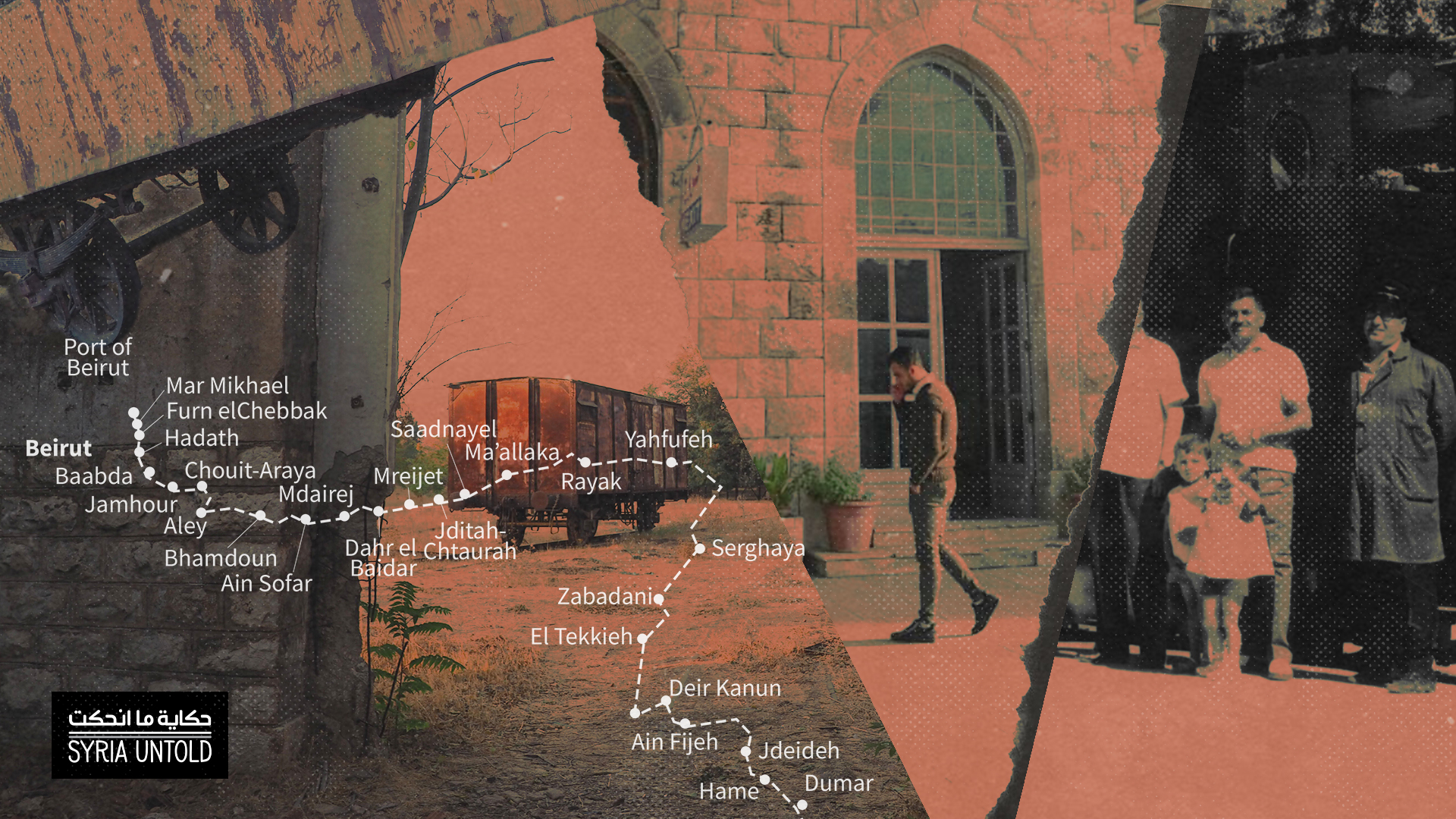

The forgotten railways of Syria and Lebanon: Tales of a missed connection

29 October 2021

After reading his diaries, I had a strong belief that Orwell walked in Syria, not in Spain. His poetic way of narrating every specificity mirrored the militarized period of the Syrian revolution in Aleppo, not just in Barcelona. The book transported me back to my abandoned photography archive. At the time, I had been boycotting the aesthetic of photography to prevent myself from drowning in my sea of nostalgia, and because of my inability to take photos.

But then I started combining Orwell’s texts with photographs I took in Aleppo between 2012-2014. The combination deterritorialized the notion of belonging. Orwell’s account of Spanish people in the streets of Catalonia alongside my photographs reincarnated the people of Aleppo. Suddenly Aleppo became Barcelona and Barcelona became Aleppo, and everything related to belonging became ambiguous.

***

“Where are you from?”

The motorcyclist repeated the question to me in English when he noticed that I didn’t understand Spanish.

“I am Dutch.” I thought this answer would be enough to let me keep walking in peace.

“You don’t seem Dutch to me, where are you originally from?” he asked with a friendly smile.

“I am Syrian.”

The answer was enough for him to widen his amazed eyes and invite me to follow him for a while. After five minutes of walking, he pointed to a road and explained: “This road leads to La Jonquera through the Pyrenees. In 1939 it was a passageway; 500,000 Spanish refugees crossed through it into France, like your Aleppo!” He continued pointing to an old three-story building without giving me a chance to process the surprise of hearing Aleppo.

“The Francoists were about two days away from defeating the rebels forever while the last president of the Republic Manuel Azaña counted the trucks here before going into exile. Each truck was evacuating paintings from the Prado Museum, other jewels and valuable state objects hidden in a secluded talc mine in this area. Then one year later, everything was sent away in secret, to be safe with the League of Nations.”

Because belonging is so subjective, nomadism became my own way to survive.

I could not resist the temptation to interrupt him when I saw not just colored graffiti on the wall with the Republican red, yellow and pink flag colors, but also a Catalan phrase scrawled next to it “Visca la Republica.”

“What does this phrase mean?” I asked.

He smiled: “Visca la Republica, viva la Republica, salute to the Republicans and all the rebels around the world.”

I felt as if I lost gravity. I did not know whether the motorcyclist was Syrian or Catalan or Spanish. I lost the feeling of non-belonging, of ambiguity, until I realized that it is impossible not to belong. I discovered there that I belong to the non-belonging. What that person did in such an intuitive conversation was exactly what I did with Orwell’s book three years before. Despite his identity and where he came from, belonging meant the same for him whether he was against fascism or dictatorship, in the past or the present and in Spain or in Syria. The motorcyclist exposed my belonging to Catalonia and I felt his homage to Aleppo.

***

The juxtaposition of photographs and texts below is a part of a work titled Homage to Aleppo. The photos (2012-2014) are captioned with excerpts from George Orwell’s memoir Homage to Catalonia.

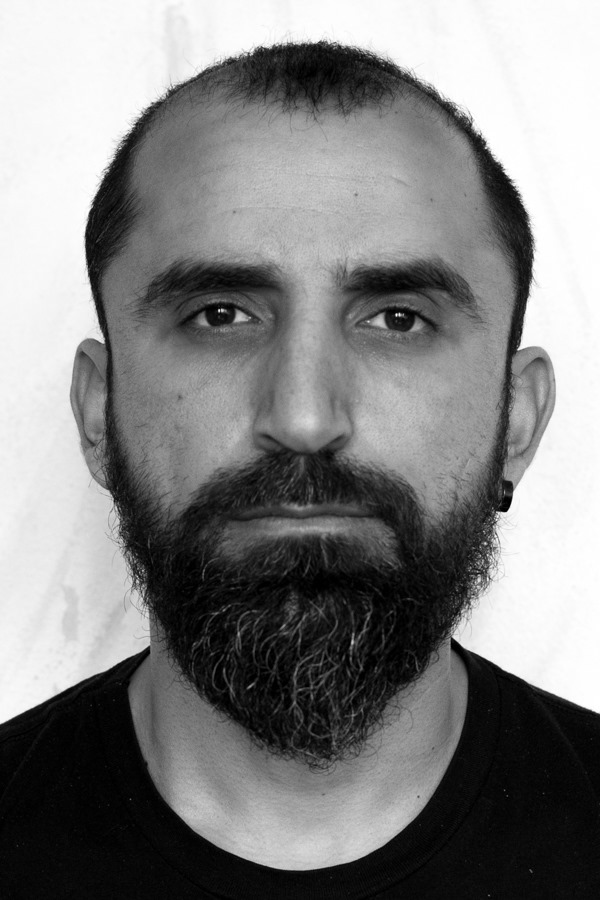

“He was a tough-looking youth of twenty-five or six, with powerful shoulders. Something in his face deeply moved me. It was the face of a man who would commit murder and throw away his life for a friend–the kind of face you would expect in an Anarchist.

Queer, the affection you can feel for a stranger! It was as though his spirit and mine had momentarily succeeded in bridging the gulf of language and tradition and meeting in utter intimacy. I hoped he liked me as well as I liked him. But I also knew that to retain my first impression of him I must not see him again; and needless to say I never did see him again.”

“The thing that had happened in Spain was, in fact, not merely a civil war, but the beginning of a revolution. It is this fact that the anti-fascist press outside Spain has made it its special business to obscure. The issue has been narrowed down to ‘fascism versus democracy’ and the revolutionary aspect concealed as much as possible.”

“…Under the seeming gaiety of the streets, their many-coloured flags, their propaganda-posters, and thronging crowds, there was an unmistakable and horrible feeling of political rivalry and hatred. People of all shades of opinion were saying forebodingly: ’There’s going to be trouble before long.’ The danger was quite simple and intelligible…”

"On our third morning in Alcubierre the rifles arrived. A sergeant with a coarse dark-yellow face was handing them out in the mule-stable. I got a shock of dismay when I saw the thing they gave me. It was rusty, the bolt was stiff, the wooden barrel-guard was split; one glance down the muzzle showed that it was corroded and past praying for."

"Glory of war, indeed! In war all soldiers are lousy, at least when it is warm enough. The men who fought at Verdun, at Waterloo, at Flodden, at Senlac, at Thermopylae–every one of them had lice crawling over his testicles."

"The bomb in use at this time was a frightful object known as the ’F.A.I. bomb’, it having been produced by the Anarchists in the early days of the war. It was on the principle of a Mills bomb, but the lever was held down not by a pin but a piece of tape. You broke the tape and then got rid of the bomb with the utmost possible speed. It was said of these bombs that they were 'impartial'; they killed the man they were thrown at and the man who threw them."

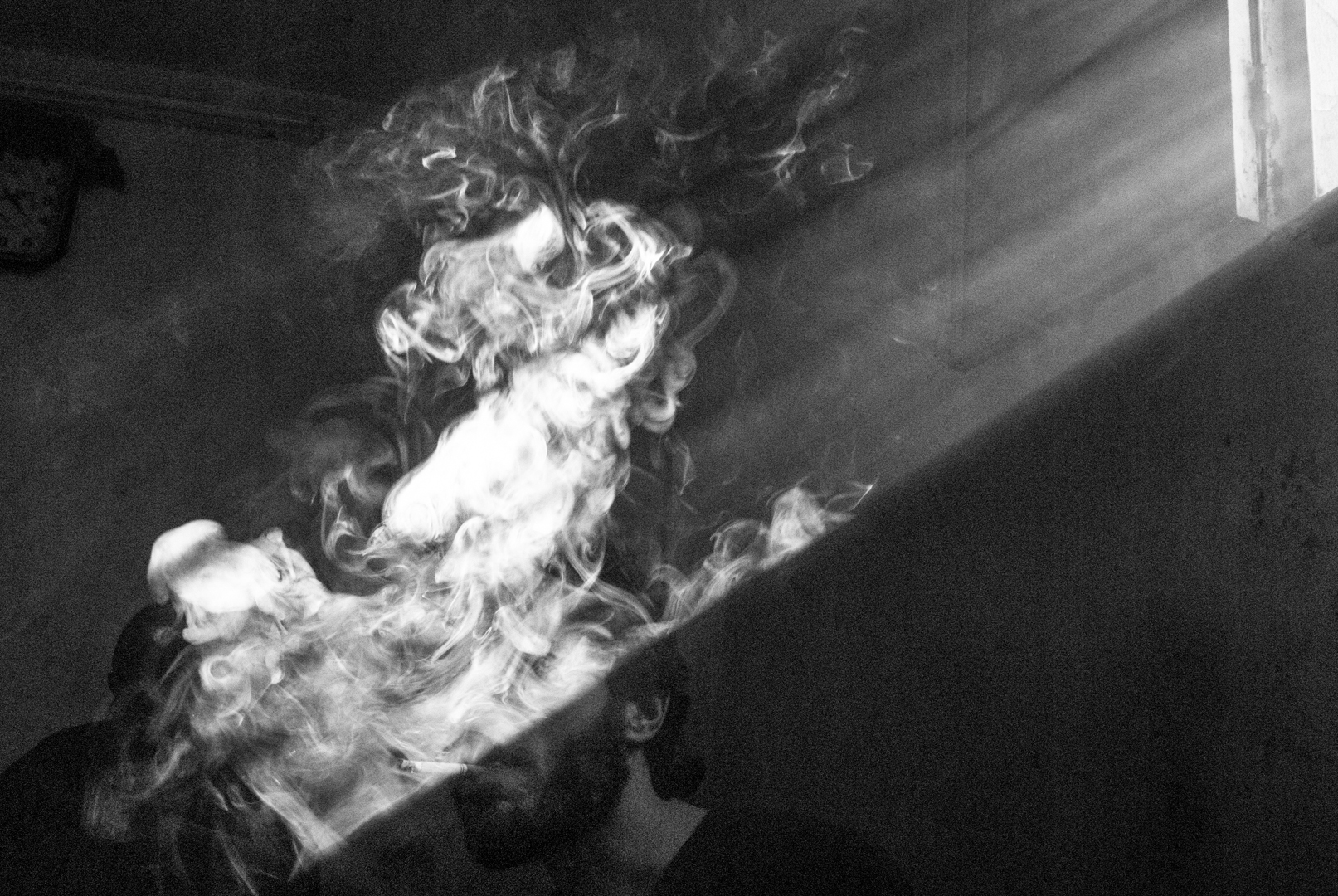

“I said that we should be all right if we had some cigarettes. I only meant this as a joke; nevertheless half an hour later McNair appeared with two packets of Lucky Strikes. He had braved the pitch-dark streets, roamed by Anarchist patrols who had twice stopped him at the pistol’s point and examined his papers.

I shall not forget this small act of heroism. We were very glad of the cigarettes.”

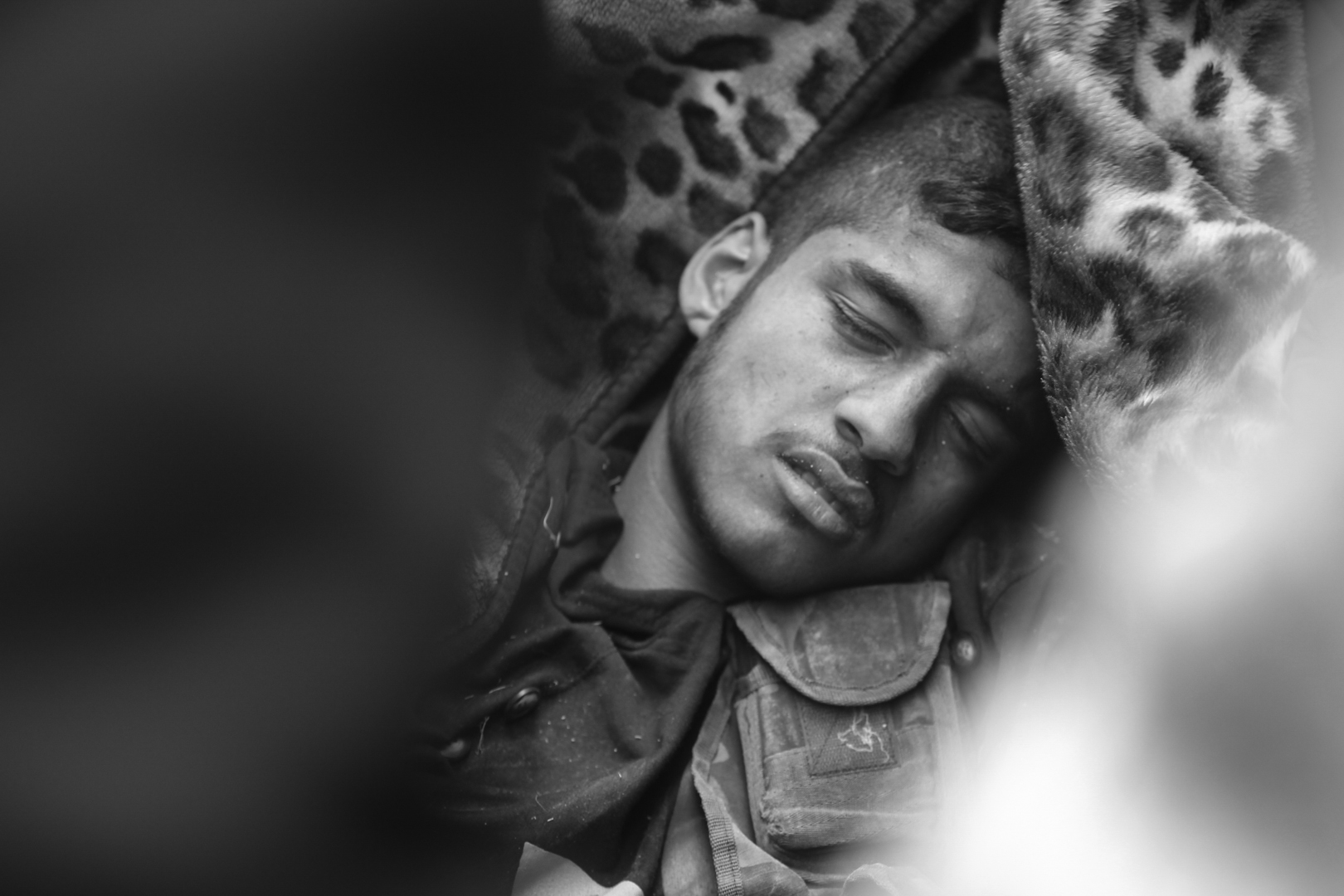

“It is not a nice thing to see a Spanish boy of fifteen carried down the line on a stretcher, with a dazed white face looking out from among the blankets, and to think of the sleek persons in London and Paris who are writing pamphlets to prove that this boy is a Fascist in disguise. One of the most horrible features of war is that all the war-propaganda, all the screaming and lies and hatred, comes invariably from people who are not fighting."

"I record this, trivial though it may sound, because it is somehow typical of Spain–of the flashes of magnanimity that you get from Spaniards in the worst of circumstances. I have the most evil memories of Spain, but I have very few bad memories of Spaniards."

*Author’s note: Deterritorialization is the severance of social, political or cultural practices from their native places and populations.