This article is part of our series on Arab photography funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, with guest editor Muzaffar Salman.

Read this article in Arabic here.

Some time ago:

“Dear, a society where the only respite consists of running errands or going to a restaurant isn’t promising at all. Leave while you have no children. You are a photographer, and your future lies in another country.”

This is what my friend Jojo told me as I waited for my turn in line to file a complaint about the internet network that wouldn’t function. I couldn’t stand the extreme cold in the air-conditioned office, so I stepped out and watched the faces of the passersby.

The men who were out shopping walked alone or accompanied by another man, while the women usually walked in groups with flocks of children, headed to the bazaar where all kinds of products were displayed and sold. What I noticed was the concern in their eyes and the dim looks on their faces.

A couple of weeks ago:

“Hello.”

“Good morning! How are you doing?”

“I’m okay… To be honest, what is happening around us has taken a toll on me. I feel down.”

“Yes. I understand. How is it going at the hospital?”

“There are still lots of patients. Like everywhere else in the country, we don't have enough oxygen or beds. It’s crazy. This is why we’re losing so many of our patients to COVID-19. May God have mercy on us.”

“Yes, I saw requests for ventilators online.”

“With the water crisis, I wonder if it’s even possible to keep up with sanitary measures and regular hand washing.”

“We don’t know how we got to this situation: an economic, social, health crisis and now the water crisis. Let’s hope it doesn’t get even worse!”

“You know, lately I've been watching the comedian Fellag, and I find him funny. At the same time, I say to myself: It was always this bad anyway, so this, too, shall pass!” We laugh.

I don't know why nothing works here in Algeria. Nothing goes well and nothing lasts. Everything fails. It is said (and this has become a proverb) that when a country fails and hits rock bottom, it floats again. But here, when we hit rock bottom, we start digging deeper. (Fellag)

This could lead some to think that we are edging toward resentment and misery while failing to resist. But we are fighting. Algerians embody a constant struggle for everything.

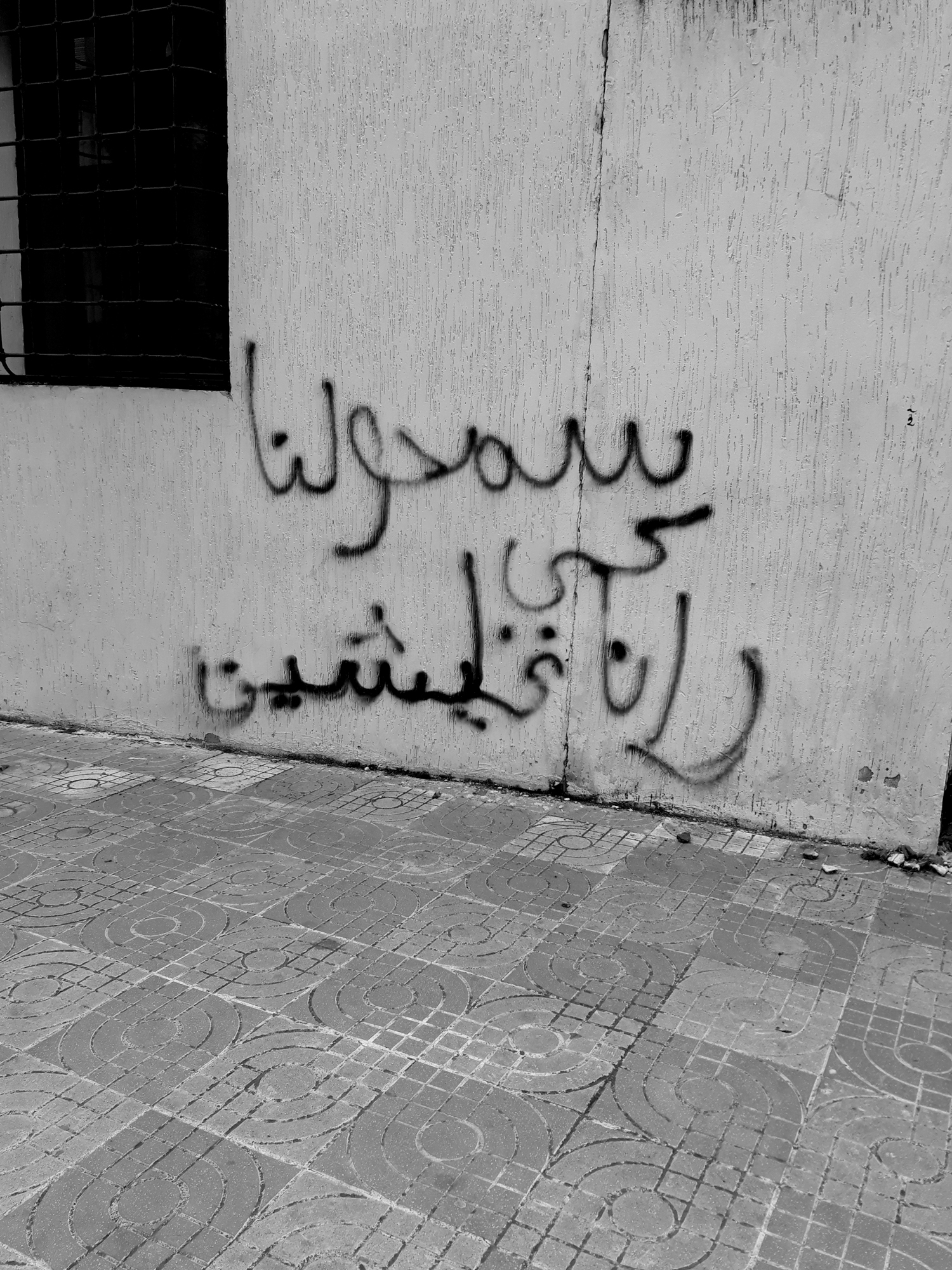

It is safe to say that life in today’s Algeria is an extreme sport. We fight so hard for survival that the slogan “Let Us Live” now expresses the inexpressible with the same intensity of our daily hardships.”

I think about the neighborhood I recently settled in. There are no garbage bins here, and waste is not collected on a daily basis. I personally find it hard to leave a garbage bag near the building or casually dump one somewhere in the street. Stray cats and dogs rip the bags in search of something to eat, so the neighborhood becomes dirty, stinky and ugly. Finding a place to throw waste has become a real daily problem.

I once took the garbage bag with me in my car to the capital, which is 100 km away from my home, to throw it in a garbage bin in a neighborhood there because I couldn’t find another bin on the highway.

I also remember the mornings when I watched dozens of people lining up in front of post offices, which have a shortage of banknotes, to withdraw their salaries. About 400 meters away from the office, I saw other people standing in line to buy subsidized bags of milk, which are cheaper than the sterilized milk cartons. I find these scenes heartbreaking and sad.

There is also the water shortage. We only have water every two days for a few hours only, from 6am until 6pm if we are lucky. Otherwise, I sometimes use the water I store ahead of time to wash my face in the morning. However, what my aunt told me the day before yesterday broke my heart: “My water was cut off for 10 days... Am I cursed?”

Add to this another set of problems such as booking a doctor’s appointment, getting a job, finding a bus after 6pm... Just thinking about it makes me dizzy.

I once read some graffiti that translated into “We are born by chance and live against all odds.” I consider this to be somewhat reflective of this situation in Algeria.

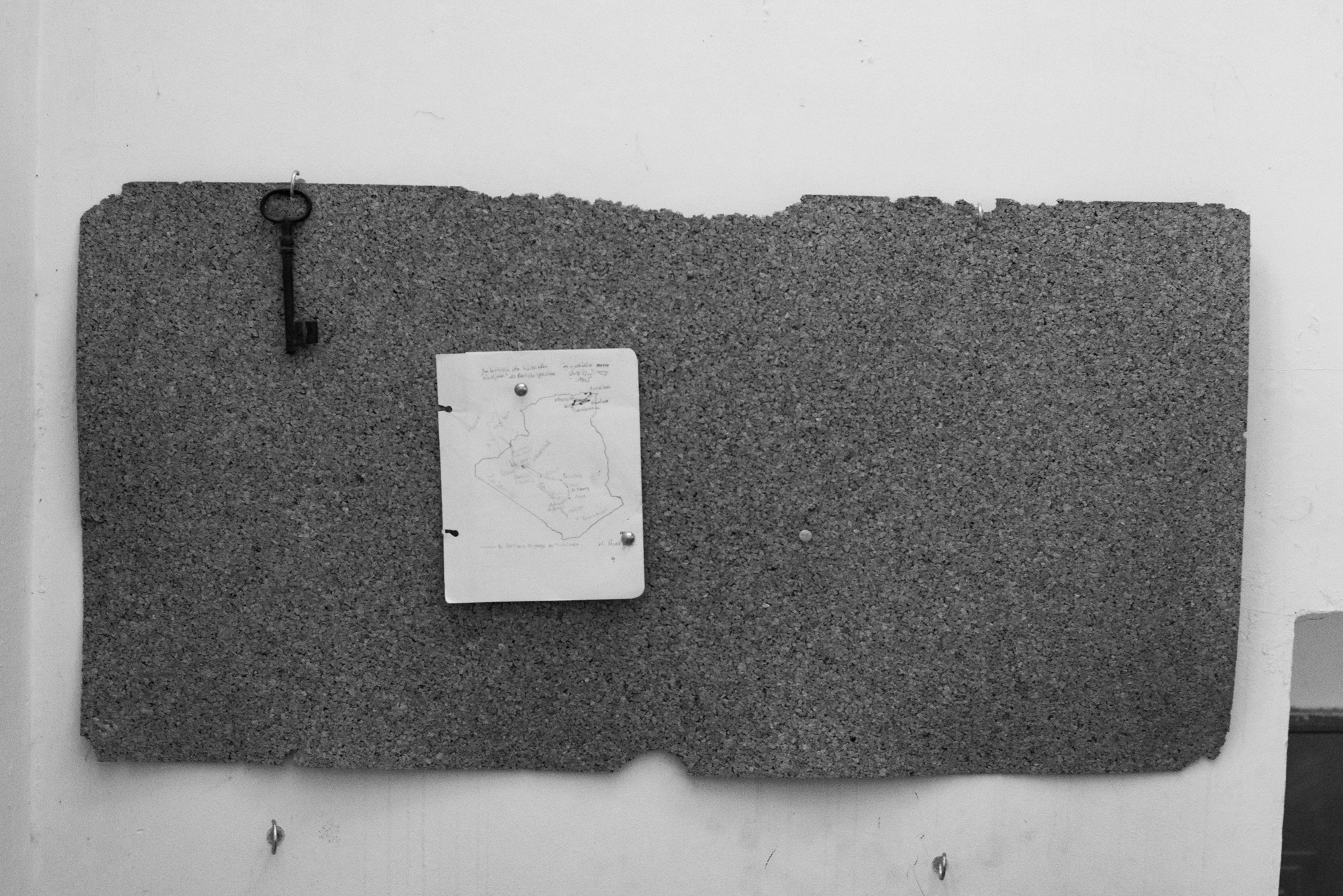

These daily struggles differ in nature from the struggles that our fathers and our grandfathers knew in their youth.

A long time ago:

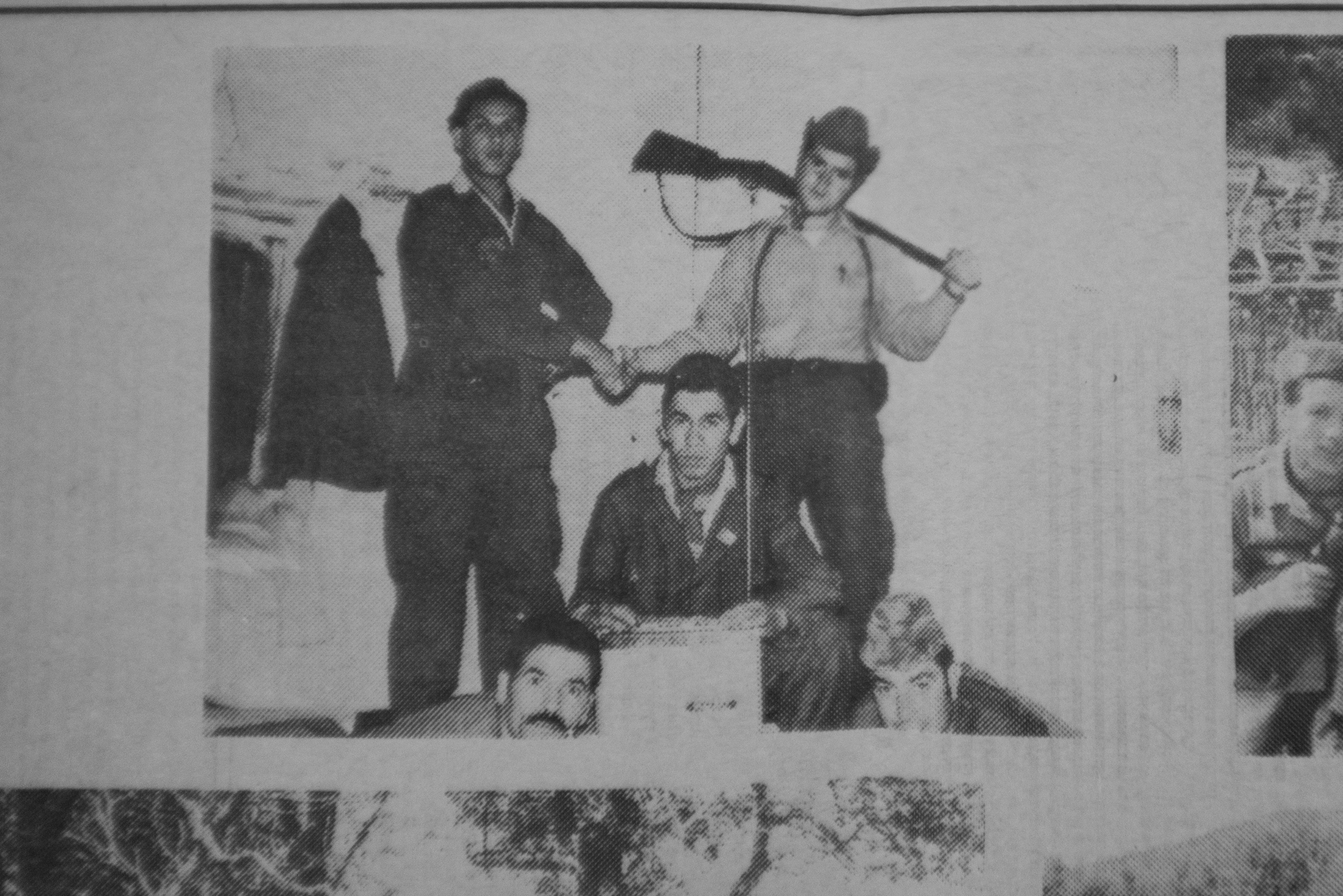

My ancestors fought against French colonialism. They endured the agony of war and the pain of deadly diseases such as typhus. They suffered poverty and illiteracy. My parents knew the woes of deprivation and were only children on the eve of the country’s independence.

The luckiest children of their generation struggled to study, and because schools were sparse, most of them walked long distances, deprived of warm clothes in the winter and exposed to the scorching sun during the other seasons.

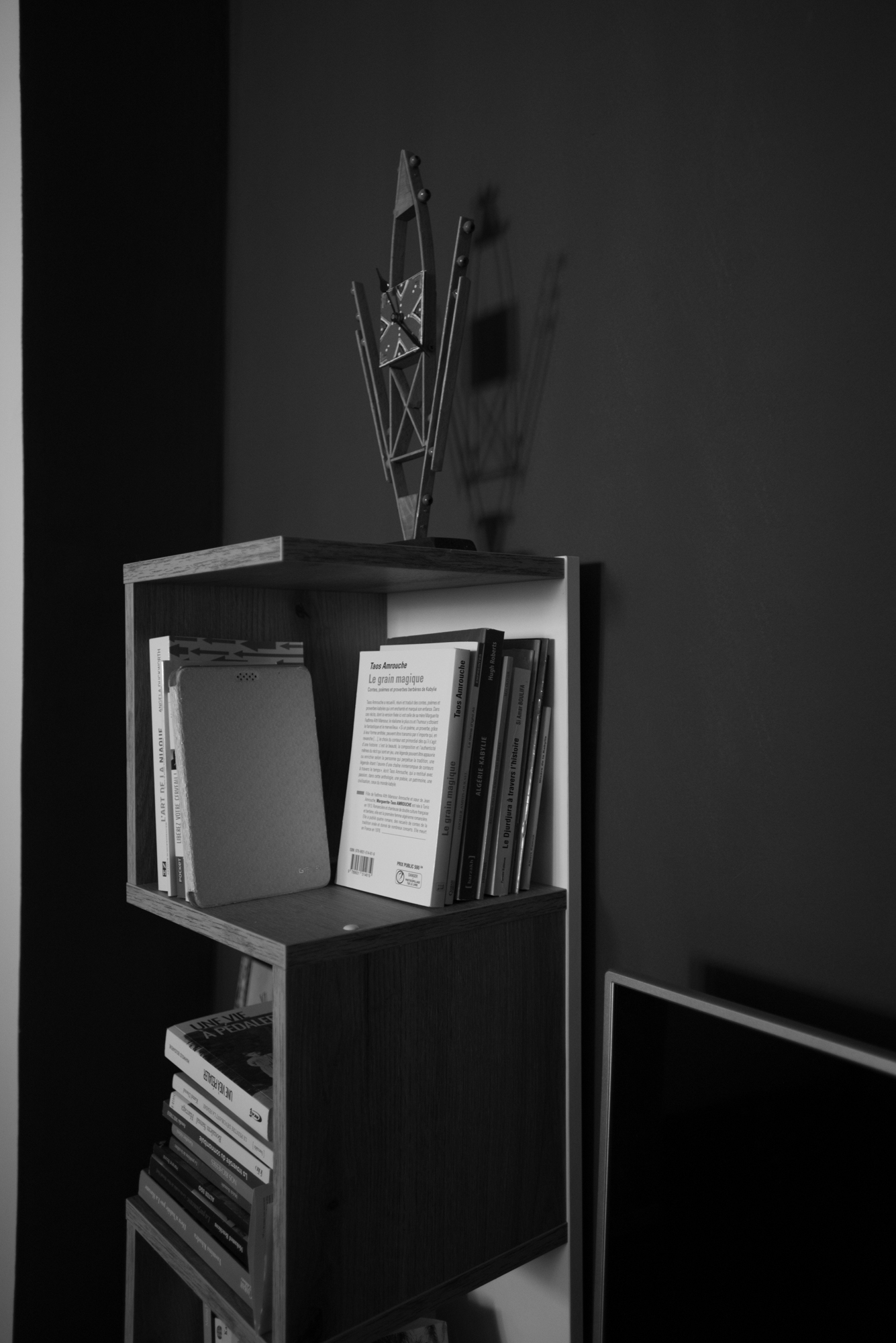

My mother, the first woman in her family to obtain a baccalaureate degree, waged a feminist struggle for her right to pursue university studies in the capital and work.

When I think about it, I realize that my parents’ generation struggled to either establish an effective educational system or to fight for the sake of the Amazigh cause and democracy.

I am also aware that my parents’ generation struggled during the 1980s, even if I don’t remember what happened because I was born after the events of October 1988. But I remember that during the 1994-1995 school year, when teachers and students were on strike, all educational institutions in the tribal regions were paralyzed for a year. Teachers wanted to demand the recognition of the Amazigh identity and teaching of Tamazight, which was subsequently included in the educational curriculum in 1995. This year or no school in 1994-1995 was called the “White Year,” and it marked my first official school year. Luckily for me, my father and mother took turns teaching me the first year program allowing me to register for my second year in 1995-1996.

During the long period of the 1990s, known as the “Black Decade,” Algerians suffered from the violence of terrorism. I vividly remember a bomb that exploded in front of my school building. I was seven or eight years old.

My cousin had headed to school before me, while I walked there with a friend. About 30 meters from the school, the explosion shook us and we ran to my grandparents’ house, where we ate lunch.

My aunt was scared when she saw me come home alone, without my cousin. She started asking us why he wasn’t with us. She ran to the school to look for him. I remember us waiting a long time until my cousin returned safe and sound. Fortunately, the explosion didn’t kill anyone, but I don't remember when we resumed our classes.

I sometimes wonder: How did people manage to live when they were forced to bear the burden of disasters unfolding on a daily basis?

In 2001, a conflict broke out between the youth and the security forces in the Kabylia region after the killing of a student in the demonstrations commemorating April 20, 1980; a symbolic day marking the struggle for the recognition of the Amazigh identity (there are people who participate in these demonstrations and others who do not because they took on a somewhat political dimension). Riots soon broke out and, given the death toll that reached 162, the year 2001 was known as the “Black Spring.” Despite the difficult circumstances, we only stopped studying when the principal asked us to do so because of new clashes that erupted near our school. At that time, I was in middle school. My classmates who lived far away had to turn around to avoid conflict zones and manage to go back to their homes.

I can recall the smell of burning rubber tires, mixed with tear gas and the images of the streets turned to battlefields.

Almost three years ago:

Finally, the memory of the peaceful movement of 2019, the “Hirak,” is still vivid.

People seemed united as Algerians took to the streets amid a festive atmosphere. Fridays became the days of group therapy, and people’s eyes shined with hope.

We can say that this movement was the last struggle of three generations of Algerians who have not experienced comfort and tranquility ever since the departure of French colonialism. All of these daily struggles to get milk, medicine or an oxygen canister for a COVID-19 patient, to find a stable job or simply a bus home after 6pm, are struggles for a decent living.

This suffering has indeed led me to wonder: Would it be worth my while to have children under such difficult circumstances? I know that when they grow up, they will be caught in a real dilemma. Should they endure the suffering of staying at home or emigrating, which itself entails another kind of suffering? We, as Algerians, love our country and wherever we are, Algeria lives in us, even if we do not live in it.

I was once surprised to hear myself saying, “I chose to stay in my country,” and then I realized how difficult it is to stay here. Leaving, rather than staying, is what requires a choice or decision. But leaving has become so natural, sort of a way out. I have not yet read the book Colonial Shock by Karima Lazali, but perhaps there I might find the answers I’m looking for.

My head is burdened, and my heart is heavy. I think of another piece of graffiti I’ve seen that says, “I grew up in you, my country, and my dream got lost in you.”

What are we leaving for our children of this fourth generation after the war?

At the end of the day, I can only say in my heart: This is life, and it goes on.

Translation from French into Arabic: Al-Kayseh Hamrouni Fadil.