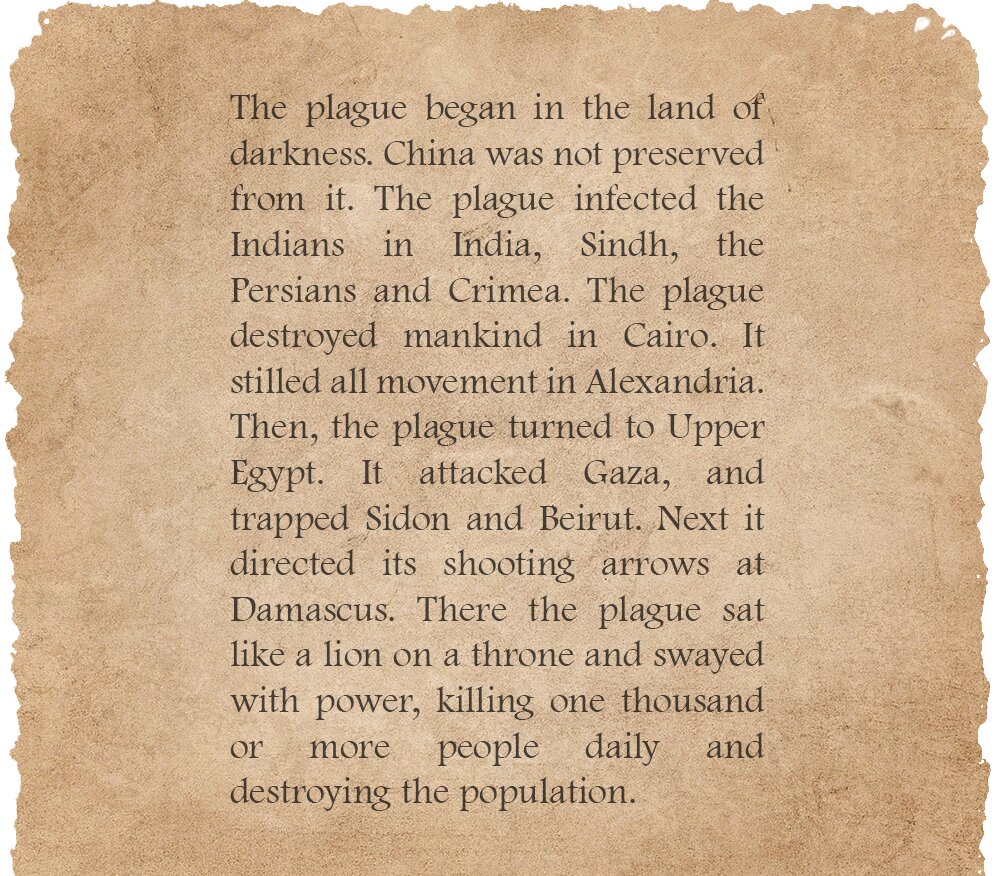

So wrote Ibn al-Wardi in the 14th century, before dying of the plague himself. Al-Wardi, a historian from what is now northern Syria, was alive at a dreadfully unfortunate time, the Black Death thrashing through the world like a monsoon.

Unlike in Europe, there is a lack of data on how many people in the Middle East died from the pandemic. Historians such as Michael Dols have suggested that the death toll in cities such as Cairo, Damascus and Aleppo was disastrous.

“Oh God,” continued al-Wardi in his 1348 Report on the Pestilence, “it is acting by Your command. Lift this from us. It happens where You wish; keep the plague from us.” Al-Wardi wrote his final words in Aleppo, not too far from his hometown of Maaret al-Numan.

During the earlier years of the Syrian revolution, protesters from northwestern Syria would flock to Maaret al-Numan for Friday demonstrations. But after years of regime bombardment, the town fell to renewed government control in early 2020. The recent videos I’ve seen of the city sketch it as a dilapidated landscape, haunted by its now fading revolutionary graffiti. Collapsed buildings litter it like seeds.

But, perhaps more than anything, Maaret al-Numan’s name sits on the shoulders of Abu Alaa al-Maari: the blind, anti-natalist, vegan, agnostic 11th-century philosopher and poet, born and buried in our embattled city and, of course, named after it. Writing three centuries before Ibn al-Wardi, al-Maari, I suppose, would have cursed at his descendants for their dying pleas. Why, he would wonder aloud, his huge frame shrugging, do my city’s people still believe that it is God, and God only, who can relieve them from this pain? Perhaps he may have written a treatise titled: God Has Nothing to Do with Your Plague, Please Stop Praying and Self-Isolate.

Critical and unbending reason was, for him, mightier than divine revelation. “There are two types of people on Earth,” he wrote. “Those who have reason without religion/ And those who have religion, but lack reason.” Bear in mind: this was not written in an isolated monastery, where al-Maari may have been free to critique organized religion, but in the middle of a caliphate—the Abbasid one, to be precise.

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

My uncle carries al-Maari’s Luzumiyat around like a talisman. When he lived with my family in Tripoli for a while, the book was a presence sturdy as our furniture. Though I was the type of child likely to pick up any book in front of her, I always kept far from Arabic literature, even when it was translated, perhaps out of fear and insecurity, or mere disinterest.

But over the past couple of years, especially as my ability to read Arabic has become somewhat more acceptable, I find myself turning to Arabic literature like a shy neighbor discovering the inhabitants of the house next door for the first time. Though I have only managed to read al-Maari in translation, his work astounds me. Why, in the 11th century, was he already telling us: "Do not desire as food the flesh of slaughtered animals / Or the white milk of mothers who intended its pure draught / for their young”? I want to know why he chose to never marry, why his epitaph read: “This was a wrong my father imposed on me / But not one I have imposed onto anyone.”

In a recent essay called “Why Read the Classics?” the Moroccan writer Abdel Fattah Kilito starts with the question: “What is the point of reading the ancients? They are not of our world. They are peacefully asleep and do not want us to wake them. Let the dead bury their dead.” Kilito goes on to tell us of his first interaction with Arabic literature in primary school, where it was compulsory to memorize al-Maari’s verses. Kilito and his classmates themselves had to swallow and spit out the verse:

The face of the earth seems to me

nothing but the bodies of the dead,

so tread lightly—

It would be a villainy, despite the passing of time,

To humiliate our fathers and grandfathers

But Kilito, decades later, builds on this verse to twist al-Maari’s initial point, arguing that we “must care for those who came before us, for our ancestors... The greatest act of respect is to not forget them, to keep speaking with them.” This, he continues, is through continuing to knead the words and worlds of our forefathers, and to hold them dear—despite the fact that our ancestors cannot understand or even follow what we have done to their language.

Several years ago, while reading Atef Alshaer’s book Poetry and Politics in the Modern World, I started a personal project. After every chapter I finished, I would write one letter to a dead Arab poet. I was following the Arab revolutions at the time, and had a deep urge to say something to or receive something from these dead poets too. “Here," I wanted to tell them, “witness what is becoming of our world, here, tell me, what do I do with this fear and this hope?”

Anyone who tries to create some form of art, I suppose, is plagued every now and then with cynicism and pessimism. Especially during periods of collapse. Why do anything, we ask ourselves, what is the point?

Maybe I want to extend Kilito’s argument a bit more. Because as the political situation in many Arab countries grew progressively worse, at least from where I was sitting, my traverse into poetry and literature became more frantic. For me, there was this sense that perhaps our ancestors had something to tell us on how best to survive tragedy, having survived the plagues and the famine and the cyclical wars and the waves of exile themselves; that, in fact, they were the ones who could care for us if only we found ways to speak with them.

Psychologist and novelist Hala Alyan wrote in April 2020 that quarantine made her want to talk to those who came before her, those who lived through the Spanish flu pandemic; her great-grandparents and the generations who went through genocide and immigration. “Nowhere does our history exist more vibrantly than in those who lived it,” Alyan wrote. “I want to line up my ancestors. I want to know how they survived.”

You can lose all familiarity and structure and perhaps the only option is to tread through foreign territory gracelessly, one step at a time.

Frankly, I’m not too sure how al-Maari would feel about any of us dumping this ancestral role onto him. Though at a younger age, al-Maari sang of his brilliance—“They know me well / How could they conceal a resplendent sun?”— the older he grew, the more he wanted his followers to stop reading his words as prophecy. “I admit to ignorance,” he would say decades after he had likened himself to a brilliant sun. “Who’ll rescue me from living in a town,” he lamented, “where I am spoken of with praise unfit?”

The notion that there could be any sort of monopoly on truth disturbed him. Indeed, to this day, there is no one way al-Maari is read or cited. There are those who will argue that he was, in fact, a believer. Others will claim with just as much certainty that he was an atheist. Historian Reynold Nicholson advised readers nearly a century ago to take al-Maari’s intermittent praise for religion with a grain of salt, arguing that it was the philosopher’s way of throwing religious authorities off his tracks.

The more I shuffle through al-Maari’s writings, the more I realize how contradictory a person he was. While that is the case with all prolific writers, and all breathing beings for that matter, his contradictions are illuminating. It’s hard to truly understand the worth and weight of al-Maari’s work from this point of view—spatially and contextually, but also given the fact that so much of his lectures have disintegrated—but he does appear, to me, as someone who will look at everything sharply and disgustedly, but also with a childish desire to make light of the details.

I read somewhere that the last color al-Maari remembered seeing as a child was red. Between the ages of four and five, he was stricken with smallpox. The disease caused his eyesight to worsen and eventually, though it is unknown exactly when, he lost what remained of his vision. He would write later on that he was a double prisoner, of both his blindness and the isolation he indulged himself in.

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

What did exile change in our narratives?

26 January 2021

You wouldn’t know of his blindness if you looked through pictures of al-Maari’s bronze statue, sculpted in the 1940s by the young Syrian artist Fathi Mohammad. The statue once stood grave, and significantly oversized, in the middle of Maarat al-Numan, depicting a turbaned man with a rather ostentatious beard. In early 2013, al-Nusra militants decapitated it. Here was a poet who, over a thousand years ago, in the middle of the Abbasid Caliphate, was actively questioning and criticizing of the notion of divine truth and was never persecuted; and here we are, a thousand years later, witnessing the decapacitation of his statue by ever-fragile Islamists.

A couple of months ago I read Jose Saramago’s novel Blindness for the first time. It wasn’t an easy read—written in blocks and endless run-on sentences and bad grammar, unnamed characters and paragraphs lasting an entire page. But it did do something I am grateful for. It begged me to sit down and ponder what a pandemic tells us about that elusive, redundant, cliched thing: human nature. It asked me to make room for the absurdity this past year has thrown at us, and to acknowledge that you can lose all familiarity and structure and perhaps the only option is to tread through foreign territory gracelessly, one step at a time.

Blindness is about a city that falls prey to an unfathomably contagious disease that causes people to lose their eyesight. The blindness is uncontrollable: it sweeps through like an avalanche of dust, hijacking people's eyes until it leaves everyone a victim. And the government in the unnamed city ruthlessly throws the blind into an old, unused mental asylum to quarantine them, with the military the main institution responsible for providing (or not providing) the blind with food and hygiene kits. Meanwhile, our main characters are reduced to their most intrinsic, basic need: staying alive when they suddenly can no longer see. Another group of inmates, who occupy the asylum as the pandemic worsens, turn to gang warfare, hoarding food and holding others for ransom. But for one specific room of blind inmates, the very first to go blind, and the ones we follow throughout the novel, there is a saving grace: one woman, identified as “the wife’s doctor,” does not turn blind and is capable of helping the others.

Blindness is gruesome. There are sections where, as a reader, you are forced to imagine shit piling up, the stench of the inmates, the unbearable difficulty and clumsiness with which they move, the sheer atrocity of the soldiers who are ready to shoot the blind, the stale and tasteless food supplies, the unpalatable smells, the endless cries of pain into the night, the descent into hell. It is also a relevant commentary on ruthless militarism and bureaucracy, and their complete uselessness in a world of disease. What does it mean, the book wants us to wonder, to live in a place where the rules no longer apply? What does it mean to know that rules will constantly be changing?

And yet, our characters push through. The doctor’s wife reads stories to the blind. “This is all we are good for,” she thinks, “listening to someone reading us the story of a human mankind that existed before us.” And when the inmates escape the asylum, two characters enter their old apartment, where they find a blind writer. The writer, though he can no longer see what he’s doing, continues to type away. Create new narratives, then, to survive. And then, the final arc of the book:

“The doctor's wife got up and went to the window, She looked down at the street full of refuse, at the shouting, singing people. Then she lifted her head up to the sky and saw everything white, it is my turn, she thought. Fear made her quickly lower her eyes. The city was still there.”

Where are the words in between the suffering, and do they make the suffering any better or more meaningful?

While writing this article, I searched for the poem I wrote to al-Maari during my letter-drafting-to-dead-poets phase. Written three years ago, it concludes: “Perhaps you wouldn’t care, but in your home town they’ve cut off your head. Your grave grows alone and cold. Me, I am trying to learn about fate and faith, and if there is a difference in between or is it always somewhere, there, in the middle.”

Another frank moment: I wrote this poem without really knowing or understanding who al-Maari was, simply with the knowledge that he was one of the greats and that my uncle, whose devotion to Arabic philosophy I’ve long envied, loved him. I think I still don’t understand him, of course. But what I am learning is that this was a man who could be plastered with many labels, easiest of which are that he lacked faith in both religion and fate. This was a man who repeated: “My life is full of pain and my death is comfort, and all human beings are slaves and captive in the soil.” At the same time, this was the same man who continued to speak and lecture and discuss until his early 80’s. I wonder: why do that if death is the only comfort, why do that if we are merely captives? Al-Maari’s pessimism, then, is cloaked in a hope for what language can make of us, where it can take us. Maybe even in faith—that despite the death, there is a lot to pick up along this ruthless parade.

Science fiction in MENA: An artistic tool for change

26 April 2021

Land, revolutions and lessons from Syria

04 May 2021

Look at his dialogue with the dead. Al-Maari's Epistle of Forgiveness (Risalat al-Ghufran), which teems with humor and wit, narrates the journey of one man—Ibn al-Qarih—into heaven, hell and what comes in between. Before al-Qarih’s ascension, though, there is a thought that plagues his mind: Please God, he prays, help me memorize poems by heart in the afterlife. Upon arrival in the afterlife, al-Qarih puts together a banquet and calls upon different poets and grammarians (which include none other than Imru Qays and Antara, and even our greatest grandfather Adam) to discuss their works and specific syntax and verses, and the notion of language and poetry in general. This is al-Qarih (or, rather, al-Maari’s) version of paradise: a paradise of scholarly debates and arguments, a paradise where language is at the heart of holiness.

Dante’s The Divine Comedy, written over 200 years after al-Maari’s death, is at best an emulation of The Epistle of Forgiveness. Both tackle the notion of ascending to the afterlife. But the difference between their visions of hell is that al-Maari’s is not simply a place for sinners but one brimming with interesting people: Muslims and Christians, rich and impoverished, honest and weird, poets and scientists.

Apocalyptic realities bring human nature into the forefront. By witnessing them, we are given a glimpse into the basic elements of what it means to be human—to be fearful, loyal, jealous, cowardly, violent, selfish and disappointed—all at once.

So, yes. I still think al-Maari would have been frustrated with Ibn al-Wardi’s prayer to God amid a plague, and would’ve prescribed his own kind of treatise. Perhaps he would have brought in his followers and sat them around his feet to tell them that a god who punishes his people by sending a plague isn’t a good god. But that does not mean that he, too, wouldn’t have prayed in one form or another. Isn’t literature, the very enactment of it, the greatest form of prayer?

In his introduction to the Luzumiyyat, Ameen Rihani writes that al-Maari was, “above all, a poet; for when he stood before the eternal mystery of Life and Death, he sheathed his sword and murmured a prayer.” And it’s true—describing al-Maari simply as a rational pessimist is a shame. He deeply believed in justice and pushed himself into witnessing the death and carnage of our lives, while arguing for pacifism.

Both before and after Ibn al-Wardi’s Report on the Pestilence, there was plague. And after Saramago’s Blindness came his sequel Seeing. Who is writing on the COVID-19 pandemic now, and the last decade in Syria, and this odd century, and what will they have to say? Where are the words in between the suffering, and do they make the suffering any better or more meaningful? In his poem “Time and Space,” al-Maari writes:

And when we ask what end Our maker did intend Some answering voice is heard That utters no plain word.

Al-Maari uttered what so many of those who came before and after him did, too: that there is perhaps no one meaning to life, that if there was, it is impossibly hard to find. But at the same time, when and if we can, we must dance toward it through words or movement or surrender. What a dreadful, potent responsibility.

Editing by Madeline Edwards