This essay is part of our series on Arab photography funded by the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, with guest editor Muzaffar Salman.

Read this piece in its original Arabic here.

I don’t remember exactly what time it was when demonstrators started gathering to protest the new WhatsApp tax. It was between five and six in the evening, and at nine I was scheduled to shoot the opening of a music festival. Time passed quickly. The protest swelled as young activists, both women and men, arrived in Beirut from outside the city. I started following the news on TV, and I saw rage grow in the street. Unexpectedly, the protests seeped into other areas and cities outside the capital.

I called a friend who was working in the music festival and asked her if the opening was still on. She said yes. As a photographer, I felt torn between my desire to go down to the street and the prior commitment I had made to shoot the festival. Of course, I preferred the street and the movement of people above everything else.

All the while, protests grew more and more, reaching Tripoli, Sidon, the south and the Beirut suburbs.

At eight I went against my will to the music festival, even as most of the attendees were themselves tracking what was going on outside, at the movements now taking over the whole country. I took pictures while following social media with my photographer friends.

The Lebanese uprising brought me back to the street, reminding me that it’s my favorite place.

I spent more than three hours in the concert venue. When the music began, some people started dancing, but I was someplace else entirely. I kept thinking about the contradictions between what I was seeing in there and what was going on outside. For a few moments I considered leaving the concert and joining the people in the street, but my work commitment kept me in place. I felt a mixture of tension, anticipation and joy. I couldn’t stop myself from thinking about the people in there dancing—were they also following what was going on outside? Would they stay for the whole concert? Or would they leave and go down to the street? Maybe some of them had already joined the party going on outside. Finally, the volume of the music rose. It was the DJ’s turn. I started taking pictures to the beat of his music, which suited my own fast, tense rhythm.

As soon as I finished the gig, I headed to where I felt I belonged, close to the people of the city.

Light and fire

Like most photojournalists in Beirut, I have a motorcycle that makes it easy for me to get from one part of the city to another and bypass the heavy traffic. This is the fastest way for us to get to what’s happening, as well as the cheapest way amid the fuel crisis. My motorcycle is an important part of my work, an extension of the camera I carry. It takes me wherever I want to go, and I park it in the city and on street corners with ease, unlike a car.

I used to take pictures of people in the city, but after the pandemic started I began taking pictures of a city without people.

That night, I rode my motorcycle downtown to Martyrs’ Square. I parked my motorcycle and ran towards the protesters. I remember the first picture I took, of a group of protesters near the al-Amin Mosque in the center of Beirut, where most of the roads by then were cut off by burning tires and any other materials available, such as iron barriers. It was almost midnight when I joined them.

I cannot describe my feelings that night, taking pictures of a popular uprising unfolding before my eyes after years of social, economic and political crises piled atop one another. The civil war in Lebanon ended with the end of the 1980s. But the period that followed was one of only fragile peace, as the chiefs of those wartime militias assumed power, which they hold to this day.

I met my friend Hasan Shaaban, another photographer, next to al-Amin Mosque. We talked about what was happening around us and agreed it was like a dream. We couldn’t believe the scenes we were seeing and photographing. I remember not sleeping at all the night of October 17. I stayed up until seven in the morning taking pictures and going from one street to another.

At four I went to the newspaper office where my friend worked and I sent some of my pictures to the newspaper. Others I published on social media, which was already overrun with amateur and professional photos of the protests. A few minutes later I went back down to the street, where I stayed until 6:30. At seven I finally went back home to sleep a little.

Returning to the street

After a few hours of sleep, I went to the office to upload photos to the computer and pitch some of them to the newspaper. I couldn’t stand staying in the office for long, so I finished my tasks quickly. I wanted to go around Beirut taking pictures.

The office has always made me feel cramped. Long shifts at a desk restrict the photographer’s eye. What good is there in surrounding a photographer with walls? Nevertheless, walls are what some newspapers in the Arab world impose, failing to keep pace with the developments of photography elsewhere, especially since these papers don’t give the same attention to photography sections as they do other sections on staff.

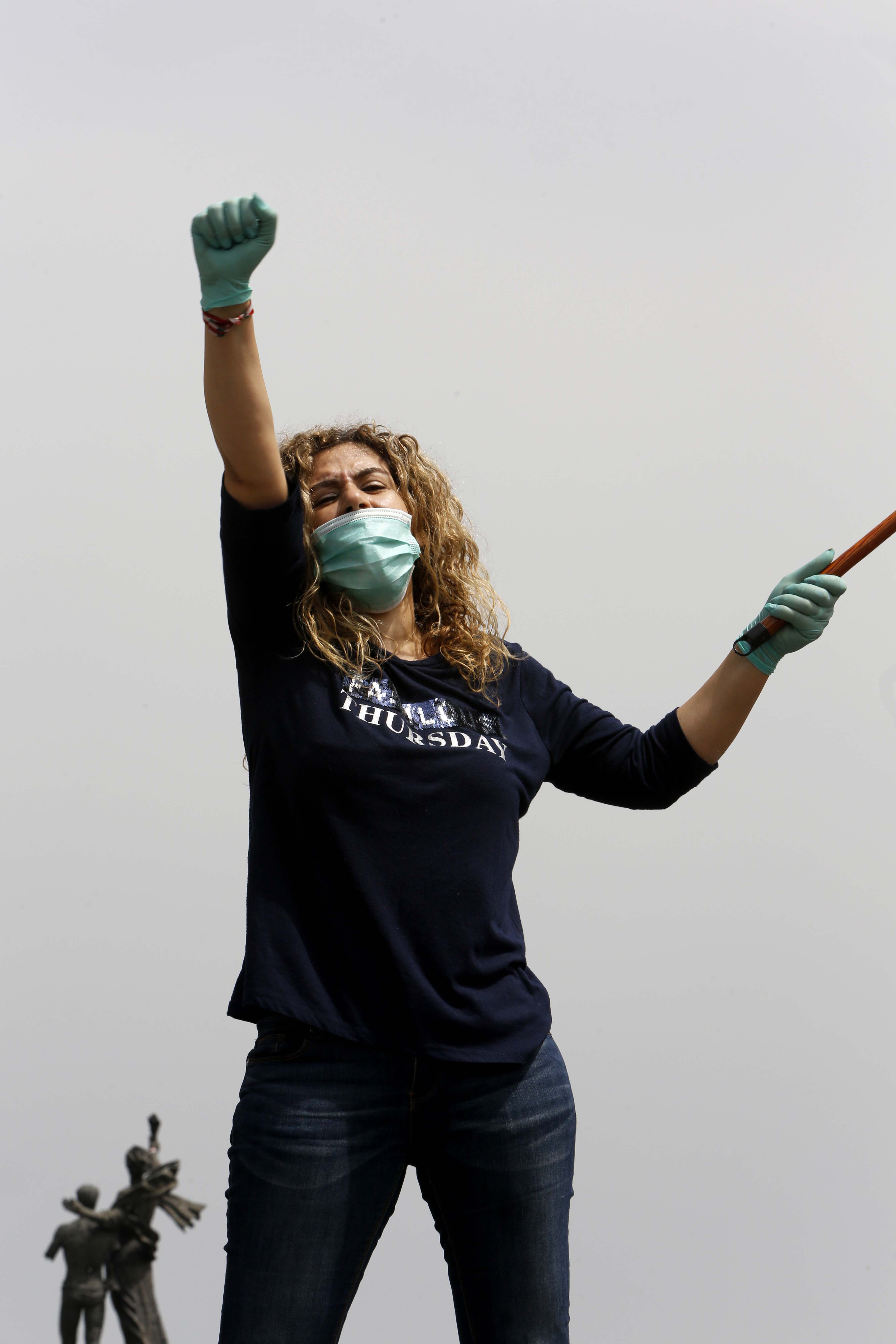

The Lebanese uprising brought me back to the street, reminding me that it’s my favorite place. With every picture I took on the street, and during every field photography trip, I rediscovered Beirut and Lebanon in different ways. Journalistic work, and particularly photojournalism that focuses on people themselves, takes place in the heart of the city and its streets, with all its violence and calm. At least for me, the camera becomes another eye with which to see the streets in countless ways.

The uprising lasted for many long months: daily protests, thousands of faces, chants, confrontations. I witnessed all of it and spent many hours, days and months in the street.

The Grand Theatre

I only knew the Grand Theatre through conversations and memories that reached me from the previous generation. It stands at the entrance to Riad al-Solh Square, and has been deserted and closed since the end of the civil war.

But the uprising freed downtown Beirut from its occupation by private investors, liberating the Grand Theatre. It opened its doors to the public for the first time in ages. I went inside and discovered the theater, just like the protesters who had overrun the building before me and torn down the wooden fence at the entrance. I took many pictures of the theater from all angles, from inside the building as well as outside and around it. I saw Beirut and its streets from its balconies, where the Lebanese flag, rather than divisive sectarian slogans, seemed to be the star of every scene.

I encountered the building often during my frequent rounds between Martyrs’ Square and Riad al-Solh Square. Security forces were constantly closing off the theater to prevent people from entering. One time, I was taking pictures of protesters from the fourth floor of the building, and I couldn’t stop myself from imagining the theater in the 1930s. What if there had never been a civil war? Could this building withstand the ongoing reconstruction of the city?

Indeed, in Beirut there are only a few theaters, cinemas and green spaces. Ours is a seaside city, yet its beaches are polluted and stolen by private investment.

The first photograph was cameraless

My visual awareness grew from images of the civil war when I was a child. In the 1980s, we lived on the fifth floor of a building next to Sanayeh Park in Beirut. One day, the bombing intensified between the eastern and western sides of the city, so my father decided we had no choice but to shelter in the building opposite ours. We stayed with our neighbors for a night or two. The bombs become even heavier, so we ran to the balcony and saw the sight of a building on fire.

I think seeing that building in 1987 was the first picture I took with my eyes, without any camera—a picture of a building emanating flames after being hit by shells. I remember the scene well. It is still fresh in my mind, like a photograph.

A week later, and by coincidence, I saw a picture of that same burning building in a magazine. Sometimes I try to remember the name of the magazine or the photographer. Do I know them? Are they still alive? Have I become friends with them? In reality, I never searched any archives for the magazine, preferring instead to preserve the picture in my memory. Maybe I’ll look for it someday, though I know this will be a long and arduous journey in a country that doesn’t care about its archives or memory.

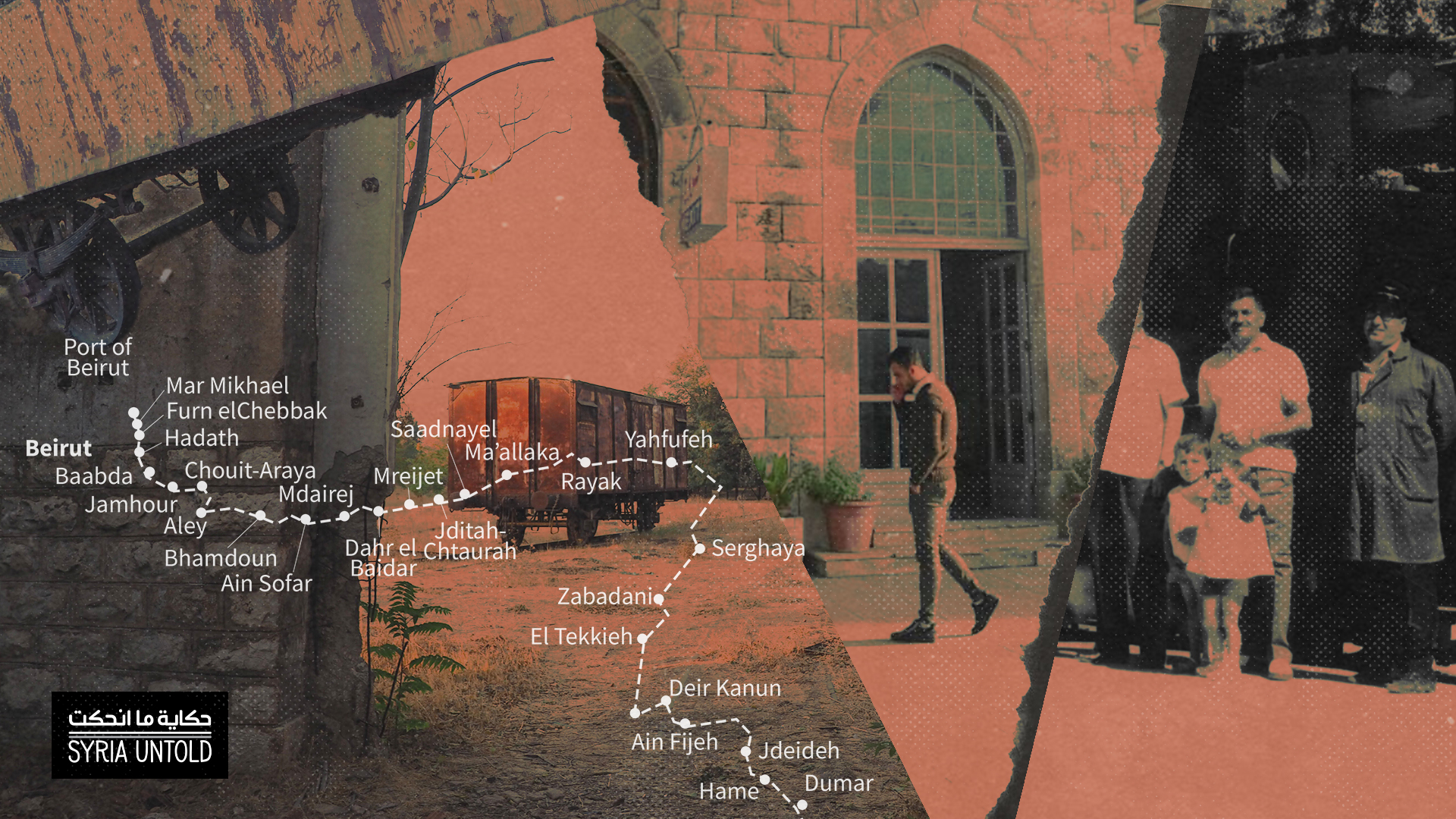

Years after that incident, I became a photographer myself, and the camera became a way of documenting and portraying events. I used the camera to impact and interact with what I saw, like what happened to me during the uprising, most of which I spent in Beirut as I was unable to take pictures in other regions of Lebanon. Time passed quickly. There was momentum on the street, though the main arteries of the uprising were on the outskirts of the city, and elsewhere in Tripoli, the Beqaa Valley and the south.

Months passed like years, especially after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, which was a silent gateway to the country’s economic collapse. I used to take pictures of people in the city, but after the pandemic started I began taking pictures of a city without people.

The civil war remains a fixed visual reference for me, often involuntarily. The empty silent streets brought me back to scenes of the emptiness that gripped the city whenever the fighting and the bombs would halt during the war. Silence would pervade for a few minutes, and the city became strange, as if it were a city in another country. And eventually came the August 4 port explosion.

Despite all the time that has passed by, I still photograph the daily lives of this city and its people. Those lives became heavier with the economic collapse, and with the grip of the political parties and militias that only claim to represent resistance.

An exhibition on the uprising, within the uprising

At the initiative of one photographer, I was invited to participate in a photo exhibition about the uprising, to coincide with the ongoing movement in the streets. It was very important to me that the show happen in a public place, as we have always lacked public initiatives like this one in the city. We hung the photos in the middle of Beirut, in the street among the protesters. I also remember that Sidon hosted a similar exhibition, but it was met with objections from the Lebanese Army due to some of the photographs showing the army’s repressive treatment of demonstrators. More than any weapon, these images are still capable of intimidating and threatening the ruling regimes.

Our pictures, which we hung on the walls of Cinema City, a movie theater in downtown Beirut, didn’t last long either. Some of them were torn down and others were burnt by political party members who attacked the protesters and torched their tents. One time they took some pictures down but I returned and hung them on the walls again. Of course, it would have been easier for me to simply take the torn picture with me, but I wanted to keep it there as a witness to what was happening in the street.

What it’s like to be Algerian: Photographic anatomy

23 November 2021

Homage to Aleppo

16 November 2021

Someone removed the picture yet again, though no trace of it remains this time. Where is it now? Did it burn in one of the city’s alleys? It was made of nylon—could someone have used it as a tarp for winter? Or maybe someone simply took it and kept it. I think it is somewhere in the city where it belongs, one way or another.

Repression...repression

Though I don’t want to draw a comparison with Arab dictatorships, I noticed in those months of uprising increased repression against those taking part in the protests. Journalists and photographers there to cover the movement were not excluded from the backlash. We saw this dynamic since the first days of the uprising.

I had photographed the protests of 2015, which broke out as a result of the garbage crisis. As security personnel tried stopping the protesters, one officer slapped my head, just as they did to other photographers who were also there. After each round of violence, I’d wonder what was going through the security officers’ heads, especially since their socioeconomic conditions are no less difficult than those of most Lebanese. Why do they beat us? What does a security guard think or feel when they beat other people, or when they go home to their family after a long day? What does he tell them? Has the regime whittled him down to a machine for repression?

In October 2019, violence against journalists, and especially photojournalists who were on the frontline with the security forces, increased. Based on my experience as a photographer, and after 20 years covering conflicts, wars and protests, I believe that the most difficult fieldwork for photojournalists in Lebanon is during protests. The movement of both photographer and camera, as well as their limitations due to the violence of security officers, become pressures that those who look at the resulting photograph will never know. True, the viewer does interact with the image, but for me as the photographer, the camera is what stands between me and the scene I’m shooting. That said, the camera cannot prevent you from being impacted by what is happening in that scene—the photographer is not merely a device for capturing images. I may have gotten used to experiencing the most violent and bloody scenes while photographing them, but all those emotions were fused into the final picture.

Time passes quickly, and with it come successive crises in Lebanon, where I live. Many of my friends have emigrated, while others wait their turns to leave as the situation here becomes heavier for everyone. The economic crisis is crushing what remains of this country. Despite everything, I try to capture the pulse of the street, the city and all their contradictions. I want to document things through images and shed light on the different aspects of the crises facing Lebanon, to write the history of this country and its situation with photographs until the day comes that the war-era militias lose their sway.