Read this interview in its original Arabic here.

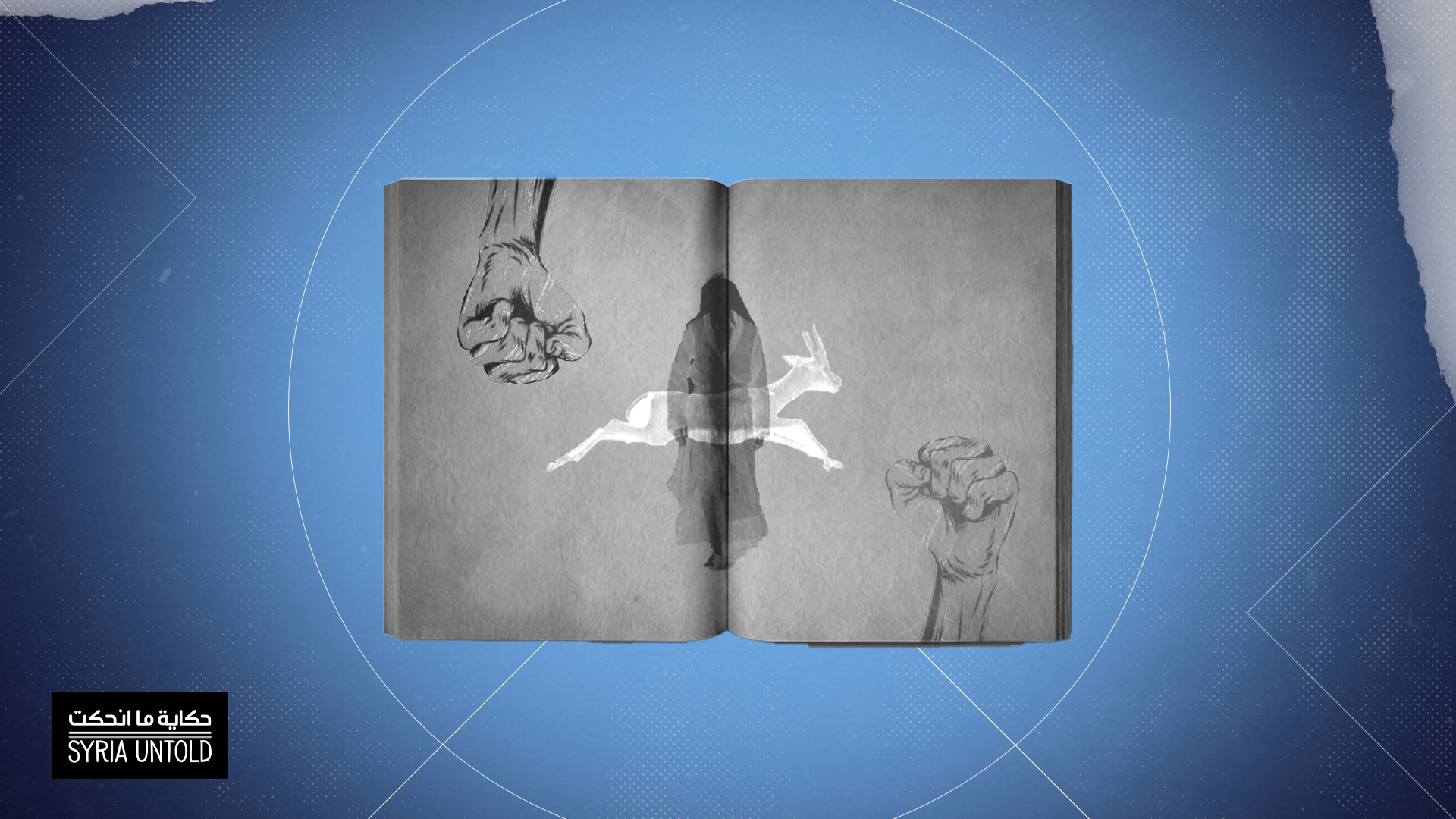

Syrian writer and poet Faraj Bayrakdar has long been known as a staunch opponent to the Assad regime. In the 1970s, he and other left-leaning writers took part in editing and publishing an underground literary zine known only as “the pamphlet.” They printed in secret at library printers and distributed the publication to friends and university students. He and other editors were briefly imprisoned for their participation.

Bayrakdar was later arrested again and remained in prison for 14 years. Syrian intelligence suspected him of involvement in the Labor Communist Party. While in prison, he faced torture and was barred from communicating with his family for seven years.

“After 14 years in prison, I felt that time is very scarce, and I don’t know how to make up for the years I’ve lost,” he told SyriaUntold in recent weeks.

Here we speak with Bayrakdar about his relationship with time after more than a decade behind bars, about his mother’s influence on his poetry, and about Homs—the ancient “heavenly city” of his childhood memories.

‘The pamphlet’

10 January 2022

Hala Abdullah: 'I believe in cinema as a means of resistance’

11 June 2021

The city of Homs means a lot to you and features prominently in your writing. What do you remember of your childhood in Homs?

Towards the end of the Ottoman era in Syria, one of my ancestors fled the qaimaqam of Homs because of a family dispute and took shelter in the outskirts of the city, in an area known as Tir Maaleh. I didn’t know this information until I began to ask questions about the repeated visits between my family and some of our relatives who had remained in the city. I was surprised by their Homsi accents, which they had kept.

And though I grew up [outside of Homs] in Tir Maaleh, I would like to talk about some of my childhood memories of this heavenly city.

I hadn’t yet started school. My mother took me to the bathhouse in the souq of Homs. On the way, I saw a cart stacked with delicious fruit, and I saw our neighbor pointing at it, telling my mother: “Take some peaches, Umm Hassan.”

I stood next to the cart and tasted this wonderful fruit. Suddenly my mother caught me and told me to put the peaches back. I didn’t understand why the peaches were forbidden to me. In our area, nobody forbade us from eating what we wanted: figs, apricots, almonds, pomegranates, grapes, watermelons. The cart owner smiled as he returned the peaches to me, saying: “Sahtein, ammou.” [Bon appetit.]

In the bathhouse, I was shocked to see that all the women were naked. It was a scene out of one of those legends I hadn’t read yet. But time sped up and stepped forward until I was no longer a little child, and I could not longer accompany my mother to that enchanted kingdom.

In sixth grade, my older brother took me with him to the city to take pictures of me. That’s when I ate the tastiest falafel sandwich and went to the cinema for the first time.

However, my most beautiful memories of Homs are from when I was a young man, not a child. That was after I finished 10th grade and moved to the city. I met the theater troupe directed by Farhan Bulbul, who became my teacher in school, poetry and life. Most of the intellectuals in Homs were friends of this troupe. Here sprouted the seeds of awareness, creativity, joy, hope, love, friendship, the meaning of life and its aesthetics, open to themselves and to the future.

To he who says Homs is a city that defies explanation

I will say she is a woman, a mirror, and an evergreen cypress that towers within the soul

I will say she is a river, a stream elegant in its disobedience.

In prison I lost the glimmer of laughter, and the majesty of it, too.

Can you speak more about your relationship with your mother? What was her relationship with your poetry? How did she cope with your long imprisonment?

Nothing and nobody can sustain me more than my poetry, and more than my mother. I’ve often asked myself why. I haven’t quite found the answer. My mother had wings that cast their shade over the house, the village, the fields. She followed along with our lessons in those early years of school, despite being illiterate at the time and unable to decipher the letters. But she learned the letters with us and through us, and by the time she was 60 she had learned how to read and write. I didn’t fit in with my siblings and my peers, and I felt that my mother was the one who most understood my social rebellions. She was the one who carried the heavy consequences of my politics and my choices in life. When I was in 10th grade, the Homs newspaper al-Aroubeh published one of my poems, and my mother couldn’t restrain her joy from anybody. She told me, it is said that poetry is the language of speaking, that my grandfather (her father) was a talented spoken-language poet as well. She thought I was worthy of his poetic inheritance.

During one of the mass arrest campaigns, many roadblocks appeared on the roads, so she helped me smuggle pamphlets from Damascus to Homs. My mother’s faith in God is deep and powerful, and she trusted me and my abilities to the extent that she ruled out any possibility of my arrest. This is why I was really worried about her after I was arrested. I wrote a poem for her from my cell to reassure her that I was doing well, which I hoped would be smuggled to her quickly. But I wasn’t able to send her the poem until almost seven years had passed, during which time I was completely cut off from the outside world.

I don’t know exactly how it happened, that my mother became one of those women whom the prisoners see as everyone’s mother. Maybe it’s because she had three sons in prison, and maybe it’s because she wrote a poem in response to my own, through detainees who transmitted her verses. Maybe it’s because she was able to convey her love for the others through her visits, or because of the times she told her stories whenever she came to Damascus to see me while I was wanted by security.

Damascus’ forgotten ‘Saturday of blood’

07 September 2021

Raqqa, at the center of the universe

16 August 2020

It struck me that my mother was present in my poems since my first poetry collection, but in my prison writing her presence became overwhelming. With and without occasion, whatever the topic of the poem, my mother found a way to make herself known. After years of this, I grew concerned, so I decided to revisit many of my poems so that maybe I could make her presence logical or normal.

Only after my release from prison did I learn the truth and extent of her suffering. She told me about the people who stopped saying hello to her, how people blamed me for destroying my future after having lived a life my peers only dreamed of. But every time she felt doubt, she stopped to say that those people were forgiven: “The important thing, my son, is that they talk about you now with a great deal of respect. They realize that you haven’t wasted your future.”

You seem to have a difficult relationship with time, similar perhaps to all political prisoners. Tell me about this relationship, about the passage of time in prison and then again after being freed. How do you spend your time now, and organize your days? Do you, in the end, feel that time has defeated you or that you’ve managed to tame it?

I said in an interview 45 years ago that I wish my day could be 48 hours long. After 14 years in prison, I felt that time is very scarce, and I don’t know how to make up for the years I’ve lost. For people like me, time in prison is more spacious than outside, though sticky, mercurial, heavy, shaky, filthy and oftentimes useless. More than being a place, prison is time. To lose money or a bet or a job is much easier than losing years of your life.

In prison, time repeats itself to the point of banality, of thirst and hunger. But when the place you’re in is narrow, it is okay for time to stretch out. In prison there is nothing to necessitate running forward, while in freedom you run and you run but you never reach where you’re going. I believe that it is possible to control space in one way or another, but time is different. I have spoken at length about my relationship to time inside prison, but I still haven’t managed to determine its exact rhythm. Maybe I should add that time in general, and particularly in prison, is a double-edged sword. I mean that it can cut you, but you can also cut things with it, or plant seeds, or reap them.

You’ve said before that you are incapable of laughing with your whole heart. When do you really rejoice, if only a little? What are the moments in which you feel a little less sadness, that you possess a little bit of joy and laughter?

I don’t know how it happened. True, my life since childhood was studded with thorns and cut through with disappointments, but I still managed to smile from time to time. Prison was different. I feel like I’ve forgotten how to smile, or that I woke up one day and couldn’t find that lost ability. It was robbed from me without a doubt, the same way years of my life were robbed, neither of which can be compensated. You can succeed in learning and mastering many things, but smiling isn’t one of them. Perhaps there are smiles and laughs that glimmer with teardrops, or that teem with something deeper. I’m talking now about full-hearted laughter and not about joy, or at least inner joy.

Many things still make me feel happy when I’m alone with myself, such as when I read a book by a young writer who has achieved a highly creative text, when I read news about a Syrian refugee who succeeded in some field, when I meet an old friend whom the prisons separated from me until we found one other again in exile, when I discover that, in our language and in our condition, the difference between singing an anthem and crying is not so vast. In prison I lost the glimmer of laughter, and the majesty of it, too. I also lost another very important thing: the blessed sanctity of bread and the enjoyment of eating it. I am the rural man whose stomach could not be satisfied with less than two or three pieces of bread—not only because they broke my molars, but also because I suffered my worst torture after asking for better bread.

The Orontes River is at once a biography of itself, of me and of Syria.

You’ve said that the Orontes River in Homs is the “master of disobedience,” and that it was your “first true teacher.” You also named your son Assi [Arabic for “Orontes”]. Tell me about your relationship with the river Assi and your son Assi: about your childhood spent living next to the first, and your days now spent beside the second.

The Orontes River is at once a biography of itself, of me and of Syria. A river of the utmost generosity, it offers everything on its banks to the public: fish, figs, pomegranates, watercress, arugula, cane, mushrooms, cranberries, birds, meadows, trees, shade, freshwater springs and nights sitting in one another’s company. The river was like this until the Baathist regime came and poisoned it with chemicals from the sugar, dye and nitrogen fertilizer factories. The water was polluted. The fish died out and the birds abandoned its banks and trees. Then the mosquitos took over, both literally and figuratively.

The river’s smells became foul and suffocating, so we, too, abandoned it both day and night. The biography of the Orontes came to summarize that of Syria. Perhaps we can find similar stories in the Barada River, the Khabour and Quweiq. My relationship with the Orontes left me with a wound whose bleeding I don’t know how to stop. The death of the Orontes was like an obituary for Syria.

I spent my childhood and young adulthood in a room with two big windows that overlooked the Orontes. One night, my dream, or my plan, was to reach the village by night without knocking on my family’s door before going down to the river. Unfortunately, the moon wasn’t in on the plan, so I wasn’t able to carry it out until the next night. I told my little brother Abed al-Wakil to come with me to the river. He walked in front of me, and I followed, remembering the space we’d covered and how many footsteps.

Suddenly my feet were confused, so I told my brother: “I think we’re at the riverbank.” He nodded his head in agreement and motioned for me to follow him. After a few meters, he stopped and pointed at a tiny, almost choking stream. This is what was left of the Orontes. Four years later, I had a son whose mother was from the city of Hama, which is tied to Homs via the Orontes River, so that’s what we named our boy.

‘Little Syrias’ in a big world

26 July 2021

From Ottoman Syria to Argentina

02 August 2021

I told myself that I would take care of this child just as the Orontes took care of me when I was a little boy. I waited for him to grow so that I could explain to him the unique qualities and secrets of the river, how it chose to flow from the south to the north, unlike all the other rivers in Syria, that his father had done something similar during the era of the Assad regime. But the boy became a young man uninterested in such matters. He was unique, and we later found that he lives with autism. Nowadays, I see myself in him, even if he is more rebellious than me. I see in him a compensation, even if symbolic, for my memories of and with the Orontes River.

You have no pictures of yourself from your youth or childhood. How did this happen? How did a picture of you appear in Le Monde despite your self-censorship of your personal photographs?

Yes, unfortunately, all I have now are my photographs from after 2000. All of my other photos from before then are gone. In the early 1980s, the regime expanded its arrest campaigns against the Labor Communist Party, and the party asked me to go into hiding. One of the precautions I took at the time was to collect all the photos of me that were in the possession of my family, relatives and friends, anticipating that the security forces could take them and know what I looked like.

I was thorough, but sometime after my release, in 1997, I was surprised to find that the French newspaper Le Monde had published a picture of me wearing my high school uniform. Someone told me that my late friend Jamil had found the picture among someone’s photos, and it was the only photo available for publication. Years before, I hid my pictures and some documents I thought were important in several different envelopes then put those in a metal box that I buried in one of the four corners of my garden.

After prison, I went back to the spot where I buried the box and found in its place a big, two-story building. That is the story of why I have no photographs of my childhood or youth. The oldest picture of me goes back to after my release from prison, when I was 50 years old.

In the 1970s you were involved with Wael Sawah, Fadia Ladkani, Hassan Ezzat, Jamil Hatmal, Bashir al-Bakr, Riadh Saleh al-Hussein and others in publishing a literary pamphlet, for which you were imprisoned. Tell us about this experience. Why was the regime afraid of a literary publication?

The political dictatorship expanded during the era of Hafez al-Assad—that is, it became a total dictatorship on the political, economic, social, cultural and media levels. Under a dictatorship of this kind, you can’t even pretend to glorify Assad or his regime except by decree from the mukhabarat, let alone work on a literary pamphlet that publishes stories and poems that don’t respect the many multiplying red lines.

The editors of the pamphlet included the best young Syrian writers, people who were fed up with the silence or surrender to this reality. This is the climate that birthed the idea of the pamphlet. Most aware and enthusiastic about the pamphlet were Wael Sawah and Jamil Hatmal, later to be joined by Fadia Ladkani, Hassan Ezzat, Bashir al-Bakr, Riadh Saleh al-Hussein, Khaled Darwish and me.

We had an internal system, or list of duties, a publishing plan and guidelines for who could publish. When we were discussing the potential name for the pamphlet, we decided not to name it at all, anticipating that giving it an actual name would expose us to prosecution on the pretext that we didn’t have a publishing license. And so, what we ended up publishing came to be known only as “the literary pamphlet.” We kept in touch with writers from the generation before ours and offered to publish their work that they couldn’t publish in the official newspapers. We published a poem by Mamdouh Adwan about Tal al-Zaatar, a poem by Ali al-Jundi, and a socially daring poem by our friend Mahmoud Shaheen.

The pamphlet wasn’t published monthly or seasonally, but rather whenever we had materials and the means to print it. After eight issues, the mukhabarat arrested Riadh Saleh al-Hussein and Khaled Darwish. When they were released two weeks later, they told us that the investigation had been all about the pamphlet, how and where we printed it, who funded it, etc. In reality, Riadh and Khaled weren’t involved in those particular matters.

The editors gathered and discussed at length what we would do. In the end, we decided to keep publishing the pamphlet.

After we published the ninth issue in the summer of 1978, the Air Force Intelligence arrested me and concealed the arrest for a few months. My experience in detention and the torture methods they used on me were worse than what we knew at the time, or what was considered customary for General Intelligence and Political Security.

When I was released, we gathered again as an editorial team. It didn’t take us long to decide to stop publishing.