This article is part two of a two-part investigation. Read part one here.

Read this article, originally published in July 2021, in its original Arabic here.

Nearly two years have passed since the announcement of an oil development deal between a little-known American company and governing authorities in northeastern Syria. The months since the deal have seen the former Trump administration, which sponsored the agreement, leave office, allowing the new Biden administration to effectively nullify it.

However, mystery still surrounds the terms of the 2020 agreement, and many questions remain over the identities of the parties involved.

Since then, observers of Syria’s oil file have been asking a number of questions. What is Delta Crescent Energy—the company involved in the deal—and who are its owners? How did a small company with no track record in oil development gain an exception from the sanctions placed on companies operating in Syria? Who signed the deal and who benefits from it? Does the deal have any political repercussions or is it primarily economic?

The first part of the investigation covered the context in which Delta obtained an OFAC waiver from the US Department of the Treasury, a document that exempts certain companies from sanctions. The waiver allowed Delta to operate in northeastern Syria. Part two will tackle the political and economic dimensions of the deal not only inside Syria, but also in the region, especially with regard to the Iraqi, Kurdish-Iraqi and Turkish roles.

Deciphering the competition for Syrian oil: Part one

18 October 2021

Syria’s lucrative detainment market: How Damascus exploits detainees’ families for money

13 April 2021

Silence in Baghdad

In November 2020, Mazloum Kobani, the commander-in-chief of the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), said in an interview with Al-Monitor that “talks between US oil company Delta Crescent and the KRG [for marketing the oil] are continuing.” The KRG, or Kurdistan Regional Government, is the official body governing northern Iraq’s Kurdistan Region.

According to Rami, a source familiar with Delta Crescent Energy and the talks to authorize its operations in Syria, Delta did not explain how it was planning on legally exporting crude oil to Turkey via Iraqi Kurdistan in a way that respects the US Treasury waiver. Rami requested a pseudonym as he was not authorized to speak with the press.

A 2020 investigation by The New Republic sparked controversy, as it cited sources who said that the initial plan of the Delta company was to mix Syrian and Iraqi crude oil in the pipeline linking Kirkuk and the Turkish port of Ceyhan, with the aim of hiding the oil production source.

The joint Iraqi-Turkish ownership of the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline has been a thorny issue in relations between Baghdad and Erbil. According to Rami, Baghdad would not allow the export of Syrian oil to Turkey through Iraqi Kurdistan.

For his part, Adnan al-Jourani, a professor of economics at the University of Basra, told SyriaUntold that “the Iraqi government should be kept informed” of any plan to export oil through Iraqi Kurdistan.

According to Jourani, the Iraqi government in Baghdad “should have issued a statement” regarding the 2020 Delta agreement.

However, the Iraqi federal government has thus far failed to comment on the deal. This is open to interpretation. Damascus, for its part, immediately put the deal under the category of “theft and assault” and “looting” of Syrian oil. Ankara also condemned the agreement, describing it as “unacceptable” and saying that it is “clear evidence of the separatist agenda” of the SDF.

Christian, a subcontractor who works with the US government in Syria, described Baghdad’s silence about Delta’s export plan as a “de facto policy” due to the Iraqi government’s inability to react at the moment. Christian requested that SyriaUntold publish his comments under a pseudonym for security reasons.

Leaders in Baghdad “do not have a political cover to control the Fishkhabour crossing” between Self-Administration-held Syria and Iraq’s Kurdistan Region, Christian added. The crossing is considered a commercial artery between both sides of the border. “And they will not do so, as this would spoil the US plan to protect northeastern Syria and would cut off the humanitarian supply line.”

The Kurdistan Region of Iraq is largely independent of the Baghdad government as far as the decision-making process is concerned. Its regions are devoid of any Iraqi federal armed forces, as they are militarily under the control of the local Peshmerga forces.

“Let us not forget that when the Popular Mobilization Forces [backed by Iran] were attacking areas controlled by the Peshmerga forces in northern Iraq, the US was very clear that the Fishkhabour crossing was a prohibited area... and Baghdad did not go beyond this red line,” Christian said.

Baghdad’s position is not the only legal obstacle that the Delta agreement may face. Experts in international law believe that “plundering” Syrian oil could constitute a war crime. This is despite the fact that the application of the principle of “people’s ownership” of the oil—rather than the Syrian government's control of it—may give the agreement a certain degree of legitimacy. That is, the company could sell oil in order to support the Kurdish factions’ ambitions for greater administrative and economic independence.

This, however, remains a “questionable legitimacy,” according to legal experts.

Erbil’s role

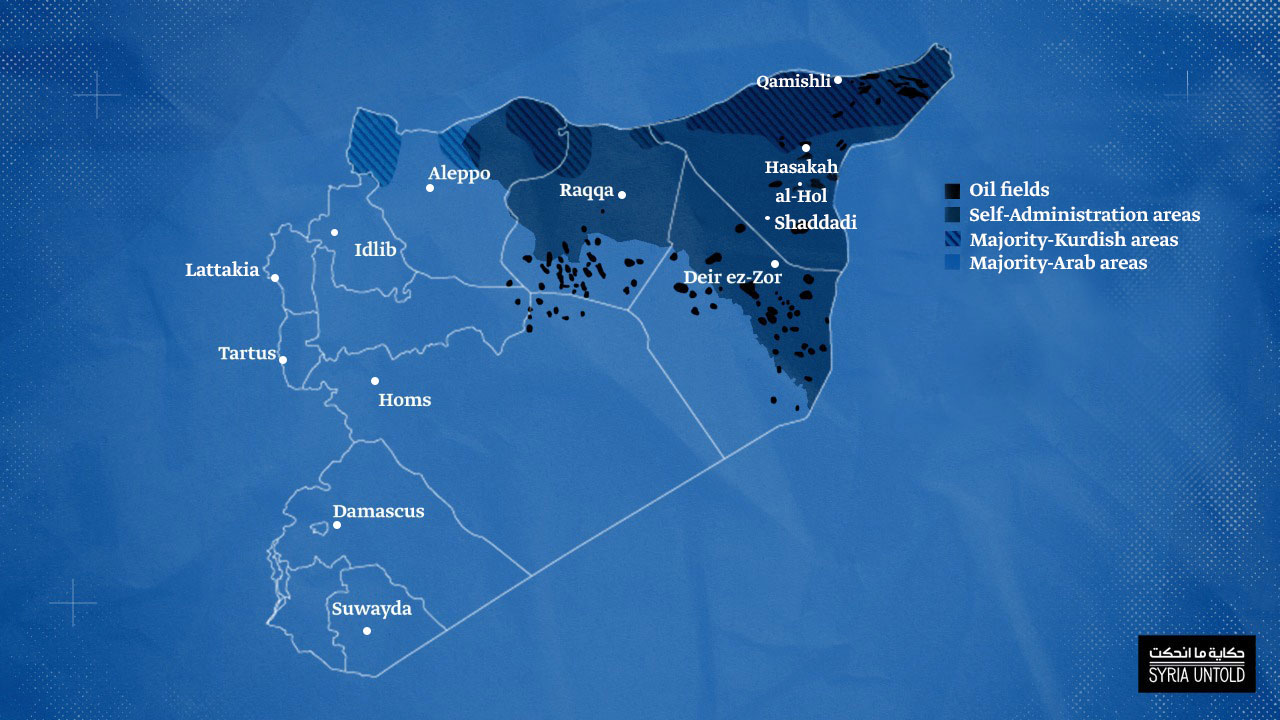

Estimates about the volume of oil smuggling from Syria to the Kurdistan Region through several border villages range between 6,000 barrels per day in 2019, according to an oil analyst based in Iraq, and 30,000 barrels per day in 2020, according to a specialized journalist residing in Erbil.

However, the black-market trade remains difficult to quantify precisely.

Considering that the Iraqi-Kurdish parties benefit from buying Syrian crude oil at cheap prices without resorting to Delta’s mediation, commercial transactions between these parties and the US company highly depend on the incentives that would be offered to the region as well as on the OFAC waiver. Such a waiver may prompt Erbil to support the agreement, as it would give it access to international markets to legitimately sell Syrian oil.

Delta Crescent Energy is not the only company that envisioned a role for regional officials in exporting Syrian oil. Moti Kahana, an Israeli-American businessman, told SyriaUntold that during his failed attempt to obtain an OFAC waiver, he stated in the application that he would sell Syrian oil to the Lanaz refinery located in Iraq’s Erbil governorate. This refinery is affiliated with the Rainfloods group owned by Mansour Barzani, the commander of special forces groups in the Kurdish Peshmerga and the brother of the Kurdistan Region’s prime minister, Masrour Barzani.

Kahana’s mention of the Rainfloods group indicates the important role of party and security leaders in the region in any project related to the transfer of Syrian oil through the territory of Iraqi Kurdistan.

Mending what has been broken

12 February 2021

Syria’s Circassian minority divided, scattered by years of war

27 September 2021

As for Delta, company partner James Reese has published a number of pictures on his social media accounts showing that he and the other Delta founders, James P. Cain and John P. Dorrier, jr., met with officials of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. These meetings apparently took place between June 2018 and May 2019, according to the dates of the photos (provided that they were uploaded shortly after being taken).

The pictures showed the President of the Kurdistan Region, Nechirvan Barzani, the former governor of Duhok, Farhad Atroshi, businessmen from the Power Gate construction company based in Duhok and at least one relative of Atroshi.

Farhad Atroshi is a close associate of Nechirvan, though was removed from office last year amid conflicts between Masrour and Nechirvan. Ali Tatar, who is close to Masrour and has a background in the security services, replaced Atroshi.

In January 2021, Kamal Atroshi, a relative of Farhad, was appointed to head the Kurdistan Region’s Ministry of Natural Resources. Kamal is close to PM Masrour, who appointed him in a bid to end or reduce the role of the former minister. However, sources say that the keys to the oil business still appear to be with Nechirvan, even after Kamal’s appointment.

These meetings may indicate that Delta has sided with the Nechirvan wing of the KDP in the oil talks.

Also, in another picture posted by Reese, Fawzi Hariri, head of the Kurdistan Region Presidency’s office, was seen with Delta’s partners at a place that featured a Saudi flag.

Upon thorough examination of the photos published on a number of online outlets, SyriaUntold found that the meeting took place at the “Seasons Restaurant” of the Divan Hotel in Erbil, which hosts the Saudi Consulate. This could signal a Saudi role in the discussions between Delta Crescent Energy and the Kurdistan Region officials, even if the evidence for such a role is yet to be verified.

Riyadh previously sent its delegates to northeastern Syria to discuss reconstruction plans and its own potential role in rebuilding. Saudi Arabia has also developed its relationship with the Kurdistan Region of Iraq in recent years.

However, an official who defected from the Syrian government ruled out any role for Riyadh in the Delta agreement, saying over Whatsapp in late 2020 that Saudi Arabia “withdrew” from the northeastern Syria file in late 2019.

The official added: “Saudi Arabia thought for a while that cooperation with the US over northeastern Syria might improve relations between the two. The Saudis earmarked $150 million for stability projects and tried to work with Arab tribes, but they discovered that the White House [under Trump] was not interested in the Syrian issue at all, and withdrew from the northeastern Syria file about a year ago.”

Current tense relations between the new Biden administration and Riyadh provide little ground for a Saudi role in the northeastern Syria file.

Political dimensions of the deal

The talks between Delta and Kurdistan Region officials cannot be understood apart from the ongoing Kurdish-Kurdish negotiations in northeastern Syria. Also important is the relationship between the Kurdish National Council in Syria (the KNC is the weakest party in those Kurdish-Kurdish negotiations) and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), which the Barzani family has been leading for decades now.

The slow mediation efforts, led by Nechirvan Barzani, aim to involve the KNC alongside the Democratic Union Party (PYD), which currently leads the Self-Administration in northeastern Syria.

According to various sources, Nechirvan Barzani has a good relationship with Mazloum Kobani, and any kind of political partnership in favor of the KNC in the Self-Administration may achieve progress in the oil talks between Delta and the KDP.

Bassam Barabandi, a Syrian former diplomat based in Washington, DC, wrote in a message to SyriaUntold over Whatsapp in January 2021: “This deal is 100 percent political, and it serves both Turkey and the Kurds and keeps the Kurds away from (Bashar) al-Assad and Russia. But if the political process stalls among the Kurds, then this project would be doomed.”

‘World War III’ in Qamishli

05 June 2020

Sultana’s story

10 July 2021

Barabandi added that “if the Kurdish-Kurdish dialogue reaches an agreement that brings Turkey on board [due to its good relations with the KDP], then this would turn the oil deal into an incentive for the Kurds.”

However, the recent military escalation between the KDP and the PKK in Iraqi Kurdistan may negatively affect the negotiations between the Syrian Kurdish parties, as Mazloum Kobani emphasized in an interview with Al-Monitor in November 2020.

There are indications that the PKK leadership in the Qandil Mountains in Iraq’s Kurdistan Region may not be satisfied with the oil agreement between Delta and the Self-Administration. In an August 2020 interview conducted by the Kurdish Sterk TV with PKK leader Jamil Bayek, Bayek echoed Damascus’ position condemning the agreement. He criticized those hoping to benefit from Syrian oil at the expense of everyday people, in an implicit reference to the Self-Administration and Delta.

Bayek’s interview followed reports that senior PKK officials had been expelled from northeastern Syria in response to US pressure to rid the Self-Administration of PKK influence.

But the end of the Trump administration seemingly dashed hopes of a Delta agreement materializing or having a possible role in reconciliation between Turkey and the Self-Administration.

Economic dimensions

Asked about the economic dimensions of the deal and the sharing of oil revenues, Co-Chair of the Syrian Democratic Council Riad Darrar said that “there is a special department in the administration that manages oil extraction, and agreements are made through this department.” Distribution of revenues subsequently done through local councils, he added.

However, when SyriaUntold contacted the Self-Administration’s Energy Authority and Economy Authority, they did not provide any information about the agreement or how the revenues would be distributed, suggesting the absence of an actual plan as well as poor coordination and transparency.

A source within the Economy Authority said that these agreements usually take place “behind the scenes,” in an implicit reference to what could be described as a “shadow administration.”

Limited options for the Self-Administration

During the war with the Islamic State and intermittent rounds of battles with Turkey, the majority-Kurdish authorities in northeastern Syria did not have many chances to market oil. This is with the exception of sales made through intermediaries to Syrian government-held territories, opposition-held territories and to the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, all the way to Turkey via Erbil. Yet the Self-Administration’s relations with all parties remained tense and even hostile.

The US Caesar sanctions on Damascus, announced in December 2019 and implemented starting in June 2020, reduced the trade volume between Damascus and the Self-Administration. The sanctions also forced the Self-Administration to focus on the export line through the Kurdistan Region in Iraq. This was in line with estimates provided by Hussein Qassem, a Syrian engineer and technical expert now living in the Netherlands. He estimated that exports to Erbil exceeded the quantities recently sold to Damascus. Qassem was responsible for collecting numerical data at oil fields in Deir ez-Zor, Shaddadi and elsewhere from 2008 to 2011. He also worked for the programming division in the Rumeilan Oil Company between 2013 and 2017.

However, Enab Baladi reported last year that the Self-Administration resumed the supply of oil to Syrian government-held territories on March 7, 2021 following a 37-day-hiatus. On March 21, an official from the government’s Hasakah Fields Directorate told SyriaUntold: “as for shipments toward regime areas...today there was a convoy of tankers.” It seems that the issue of selling oil to Damascus continues to depend on the economic grievances of the Self-Administration.

American withdrawal reshuffles the deck in northeast Syria

31 December 2018

Aid for sale in Syria's northwest

05 April 2020

As for the supply of oil to the opposition areas, makeshift refineries (known as harragat) in which “Kurdish” oil is refined have been repeatedly targeted by missiles over the past year in the northern countryside of Aleppo. The accusing finger is pointed at Damascus or Moscow, although such targeting may serve Turkey in the first place.

In March 2021, SyriaUntold reached out to two military sources from the Ankara-backed Syrian National Army, who are present in the area that witnessed the strikes. The two sources suggested that there was an implicit Turkish-Russian agreement to “economically besiege the Kurds.”

“The Turks…are the primary beneficiaries [of such bombings] as the alternative, meaning diesel, gasoline and gas, would come from Turkey,” one of the two sources said.

The second source added that refined oil derivatives from the SDF regions are sold in areas controlled by the Syrian National Army at prices that are about $25-30 cheaper than European derivatives coming from Turkey.

Damascus is taking advantage of these attacks on the harragat refineries as a pressure card on the Self-Administration to sell oil exclusively to the Syrian government. The economic sustainability of the Self-Administration thus remains linked to multilateral political maneuvers.

Finally, the oil agreement between Delta and the Self-Administration seems to be more political than economic. It did not appear capable of achieving guaranteed profits given the obstacles that would be faced by any foreign company seeking to invest in the area, as a result of Western sanctions and the ongoing war and uncertain future of the majority-Kurdish administration. Add to this the instability that was plaguing the US political scene when the company obtained the license—that is, in the year of the US presidential election.

Many of the sources whom SyriaUntold contacted during this investigation said that under the Biden administration, the future of the Delta agreement is politically insecure, as recently confirmed by the non-renewal of the OFAC waiver.

Experts pointed out that the Kurdish-led Self-Administration needs an international trading partner to guarantee the future of its economy, meet the needs of the people of the region and gain further legitimacy at the international political level. It is not easy for an untested company like Delta to satisfy all the parties benefiting from the Syrian oil trade, be they countries, smuggling networks or groups in between.

Damascus remains opposed to the Delta agreement, as Baghdad remains silent, raising many question marks about its silent position. Ankara could implicitly approve of the agreement and publicly oppose it, but the fact remains that it is threatening the future of the Self-Administration on a daily basis.

More importantly, after more than a decade of war and years of deprivation before that, the living conditions in northeastern Syria remain poor and dependent on international understandings. There is little transparency on the part of the local authorities and the companies contracting with them regarding deals that should be in the public interest.