This is part one of our English translation of an extensive interview with Syrian actor Hala Omran. Read this interview in its original Arabic here.

Hala Omran is a theater artist, actress and singer living in France. She graduated from the storied Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts in Damascus in 1994, afterward continuing her training and branching out into theater and film.

She played prominent roles, such as Nina in the play The Seagull by Anton Chekhov, as well as appearing in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire and numerous other plays. She has also worked with stage directors and choreographers such as Cherif, Pascal Rambert, Marcel Bosonnet, David Pope, Nolo Faccini, Suleiman al-Bassam and J. Kristanoff Saiss, Mehdi Dehbi, Olivier Letelier, Ali Shahrour and Mehdi Georges Helou.

Omran has also taken on leading roles in films such as Bab al-Shams by director Yusri Nasrullah (an official selection at the Cannes Film Festival in 2004), Sacrifices by Ossama Mohammed (Cannes Film Festival official selection in 2002) and Under the Roof by Nidal al-Dibs.

I’d like to give you the space to introduce yourself to readers. What brought you to the acting profession?

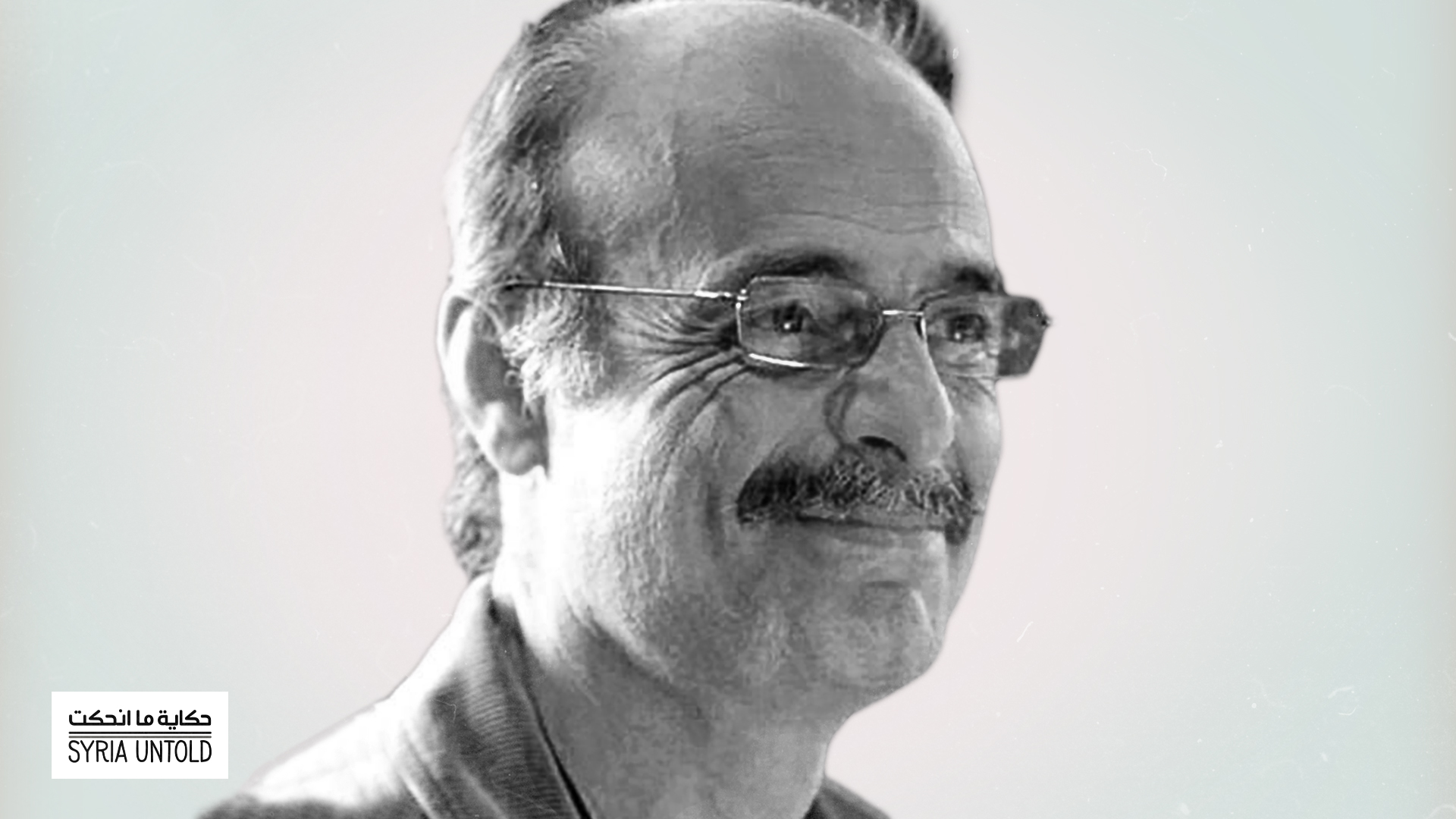

I was born in Damascus in 1971. My family came from Tartous in the 1960s alongside a wave of migration from the countryside and smaller cities to the capital. My father, Muhammad Omran, was a poet and editor at al-Maarifeh and al-Mawqaf al-Adabi magazines. He later became editor-in-chief of al-Thawra al-Thiqafi.

At the time, the sectarian way of thinking wasn’t prevalent. I even thought I was Christian because we lived in the predominantly Christian al-Qasaa neighborhood of Damascus. At first, I went to a private school, but then I transferred to a public one. There, they separated the students by religion because of the religious education class. My friends all said that they were Christians, so I did, too. It seemed completely normal to me, but the teacher asked to meet with my mother and told her she needed to explain to me that it was impossible for me to be Christian with a father named Muhammad!

Hala Abdullah: 'I believe in cinema as a means of resistance’

11 June 2021

Soudade Kaadan: 'Magic realism sneaks into all of my films'

19 July 2021

That was the moment in which I became aware of all those differences around me. Still, it didn’t have a big impact me; I just wanted to stay with my friends. I think living in the al-Qasaa neighborhood affected my life a great deal. It was a mixed area, and the neighbors who lived in our building were from all sects: Christians, Muslims, Jews. The general character of the neighborhood was Christian, but I remember in the 1970s there being a large number of Jewish families. I can say that I was fortunate for having spent my childhood in an environment of sectarian and religious diversity, among religious minorities that would later disappear from Syria. The Jews in our neighborhood lived ordinary lives until the 1990s: a Jewish butcher, a Jewish pharmacist, a Jewish doctor, etc. In the 1990s, through, they gradually began to disappear from the neighborhood.

Because my father worked in the cultural sector, our home became a meeting place for intellectuals. It was an open house for artists, writers and thinkers from all over Syria and the Arab world. We had nighttime gatherings, parties, singing, dancing and poetry. This was every day, until 1982. It got to the point where we children had no place to sleep because somebody would be sleeping in our room. We lived a life that looked like the movies: noise, colors, laughter, hustle and bustle, shouting and verbal altercations. My mother had a beautiful voice that filled our evenings with song. New poems surrounded us. Composers came over with new songs and lots of smoke. On top of that, my parents used to take us to the theater, so we could watch children’s plays and puppet shows. We also used to go to the National Theater.

I saw theatrical performances by Muna Wassef and Asaad Fiddeh, as well as shows directed by Fawaz al-Sajer. All of these made me feel early on that I wanted to be an actor, despite having never acted or stood on a stage in my life. I was too shy to express myself. Still, I remember that sentence running through my head constantly at the time: “I want to be an actor.” At school they held annual celebrations and put on silly shows, but I remember how shy I was and how I avoided participating. Then in ninth grade, the school decided to give us an acting workshop, and the actors Hussam Eid and Ziad Saad (if I’m remembering correctly) came to lead the class.

On the other hand, at home I was the one who lent the house a special atmosphere. My audience was my mother and father. I’d play Azerbaijani music tapes and wear strange clothes. I’d change around the lighting in the living room and then start dancing. I wasn’t exactly acting, but it was something in my head. I’d choose a specific place my my mother and father to sit so that I could perform my expressive dances for them. I also wrote poetry in my early teens.

I was free when I was a child, and now as I grow older, I’m approaching that same childhood freedom.

I was always writing sad, tragic poems and cried a lot in my room. I’d write poetry and cry without knowing the reason, without knowing why I had those feelings. Once I dared show my father one of my poems, and he reprimanded me: “You’re a 13-year-old girl, why are you talking about death? What do you know about it? Why all this sadness, where did it come from?” I read a lot of poetry at the time, including Federico García Lorca and Rafael Alberti, as well as poetry by my father and others. There was a great deal of sadness and pain in those poems.

I was diligent in school, and earned my baccalaureate. I decided that I wanted to study art. I applied for a dance scholarship and was accepted to travel to Czechoslovakia. While preparing to travel, I enrolled at the university. Because I had such high grades, I signed up for the College of Pharmacy. I began studying and finished my first year, stilling waiting to travel for the dance scholarship. In the end, I decided not to travel, instead enrolling in the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts in Damascus.

Within the margins, and breaking free: Syrian cinema

23 January 2021

Mohamad Al Roumi: Cinema is always necessary

11 March 2022

If you had ended up traveling to study dance, maybe you would have become one of my teachers at the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts, in the expressive dance department.

It is possible, but unfortunately I didn’t go to Czechoslovakia. I told myself that I didn’t need to travel, that I wanted to study theater and go to the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts. And so that’s what happened. I applied for the entry exam after my father told me that he wouldn’t intervene on my behalf to get me accepted. But in any case, they accepted me to study at the institute without any intervention. That place gave me the first acting experiences of my life. I had read many plays from my father’s library before starting at the institute: everything that had been published within the Arab Theater Series, which was printed in Kuwait..

Can you speak more about your entry exam, and the monologues you chose to perform?

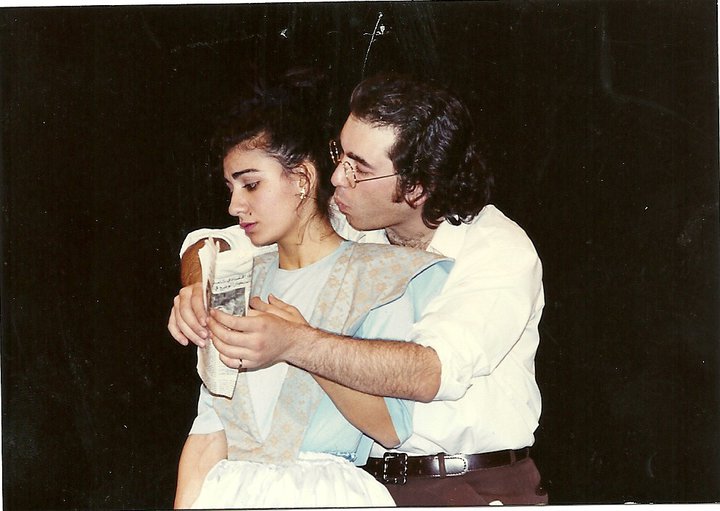

In those days we had to present a theatrical monolog from an Arab or international play, as well as a song and then a pantomime scene. I was at a loss over which text to choose, but in the end I chose a monologue belonging to the character Nina from the play The Seagull by Anton Chekhov.

Until today, when I re-read that monologue, I cry. That character, with whom I performed my entry exam, became one of the most influential theatrical characters in my life. I don’t know why, but I feel that Nina resembles me somehow.

One of the most difficult parts [of the entry exam] for me was the pantomime scene. This way of performing was strange to me, and I didn’t feel that I had enough imagination to do so. It’s a belief that stayed with me for a long time afterward.

Do you know why you felt this way?

The truth is that I have no idea why I felt this way, and I didn’t search for the reasons. I discovered later that do, in fact, have the imagination to do my work! Now as I think about this my mind goes back to the idea of freedom. I was free when I was a child, and now as I grow older, I’m approaching that same childhood freedom. I see this as very important. It’s what makes my feelings about the acting profession beautiful, because it’s a free space that allows for play. That sense of play in life, and in acting, is my main feeling now.

‘I fell in love with cinema’

23 August 2021

But when I was at the institute, I had problems with some things, such as comedic performance. Whenever I was given any role in a comedy, my heart would start beating fast. I’d immediately start thinking about how I was unable to play that kind of role. I was too serious at the time. Crying came easy to me—if you looked at me, I’d start crying right away. I had a real problem, though, with any kind of theater that required exaggerated performance and movement techniques, such as commedia dell'arte or other slapstick genres. I felt like I couldn’t do the types of performances that required a lot of play.

The first time I understood the value of play in acting is in my fourth year, in a first-semester project, which was directed by a visiting Russian director. We were doing a production of Checkhov’s The Seagull, and by pure coincidence, I was given the role of Nina. The way that the director worked with me in portraying Nina was full of play. Nina transformed into a comedic character. She faces many tragic situations during the play, but she remains lighthearted and funny. This director changed my relationship with and understanding of the art of acting. She made me understand the true meaning of play in theater.

Do you remember the director’s name?

Tatiana Arkhibtsova.

What year did you start at the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts?

1990.

That was a very peculiar time for Syria: the end of the civil war in Lebanon, and the continued Syrian occupation of that country, and soon afterward the First Gulf War. How would you describe your political awareness at that time?

Zero. I had no political awareness. I didn’t have a relationship with any political party—not even the Baath Party, despite the numerous attempts of the schoolteachers to get me to join. But my refusal to join the party didn’t come from any particular political stance. I just felt uninterested.

Do you think you were impacted at all by your father’s politics?

My father was one of the old Baathists, the activists. He was arrested for belonging to the party in the 1960s, before the party took control of political life in Syria. He was an activist like the rest of my family—aunts and uncles—but he withdrew from the party in the 1970s. Just to clarify, my father was never a political dissident, and I don’t come from an opposition family. It was just that the idea of belonging to a political party wasn’t present in my family. As you know, political engagement is forbidden in a country like Syria, and may lead you to the unknown.

Can you tell me about how you ended up in France?

I went there for a workshop with a director who I would later work with in 2000. He had come to Syria in 1998 to search for actors to participate in a production of Gilgamesh for the Avignon Festival. He wanted a cast made up of American, French and Arab actors. So he came to Syria and chose me alongside Amal Omran, Muhammad al-Rashi, Ramzi Shokair and Jamal Shokair. Then he chose me and Muhammad al-Rashi to come to Marseilles to do a workshop with him that included the French and American actors he had cast in Gilgamesh. It was a long workshop. We did a lot of voice, movement and dance training. Then in 2000 was the moment the actors all gathered to perform Gilgamesh. We performed in France, then started a tour in other countries. After that, I starting spending more time in France than in Syria.

In Paris, I had a subscription for the cinema. On days when I didn’t have any work to do, I’d go to the cinema in the morning and stay there until nightfall. I’d watch a film, then go out for coffee, come back for another film, go out to get a drink or something to eat, then return to the cinema, and so on. Sometimes I’d watch four movies in a day.

In 2002, you were in the film Sacrifices by Ossama Mohammed. There is something exceptional about the structure of the film, which touches on the patriarchal structure in society, especially in Syria. The stylized trio of women in the film, alongside the mother (played by Maha Saleh) and the grandmother (Nihal Khateeb), opposite the male bloc (the three brothers), father and grandfather, reveals levels of symbolic conflict. There is also another hierarchy between the women themselves within this patriarchal society. Can you discuss how that female hierarchy is obscured by the patriarchy? How did you create that stylized, exaggerated performance?

At the very least, I can talk about how Ossama worked with me personally. There was a lot of choreography in the form of performance and movement. This is due also to the way that I work, and the way Amal Omran works, the kind of performance that we do. Ossama makes you think that way. He works a lot on rhythm, choreography and the movement of the body in space. Even the smallest movements and actions were deliberate; nothing was accidental.

Ossama worked with me a lot on sensory things, due to the nature of the character I was playing. Sensory, meaning smell, taste and touch. He pushed me to fully perform through those actions. Even the sounds accompanying certain actions were important to him. We did lots of retakes, because Ossama is a very demanding director. But that’s something that makes me happy, because I’m a demanding actor. It was so much fun for me. I wasn’t convinced of my performance, and always felt that I could do better with retakes. That was a feeling that I had throughout the process, and one that Ossama shared. It brought us together in our work.