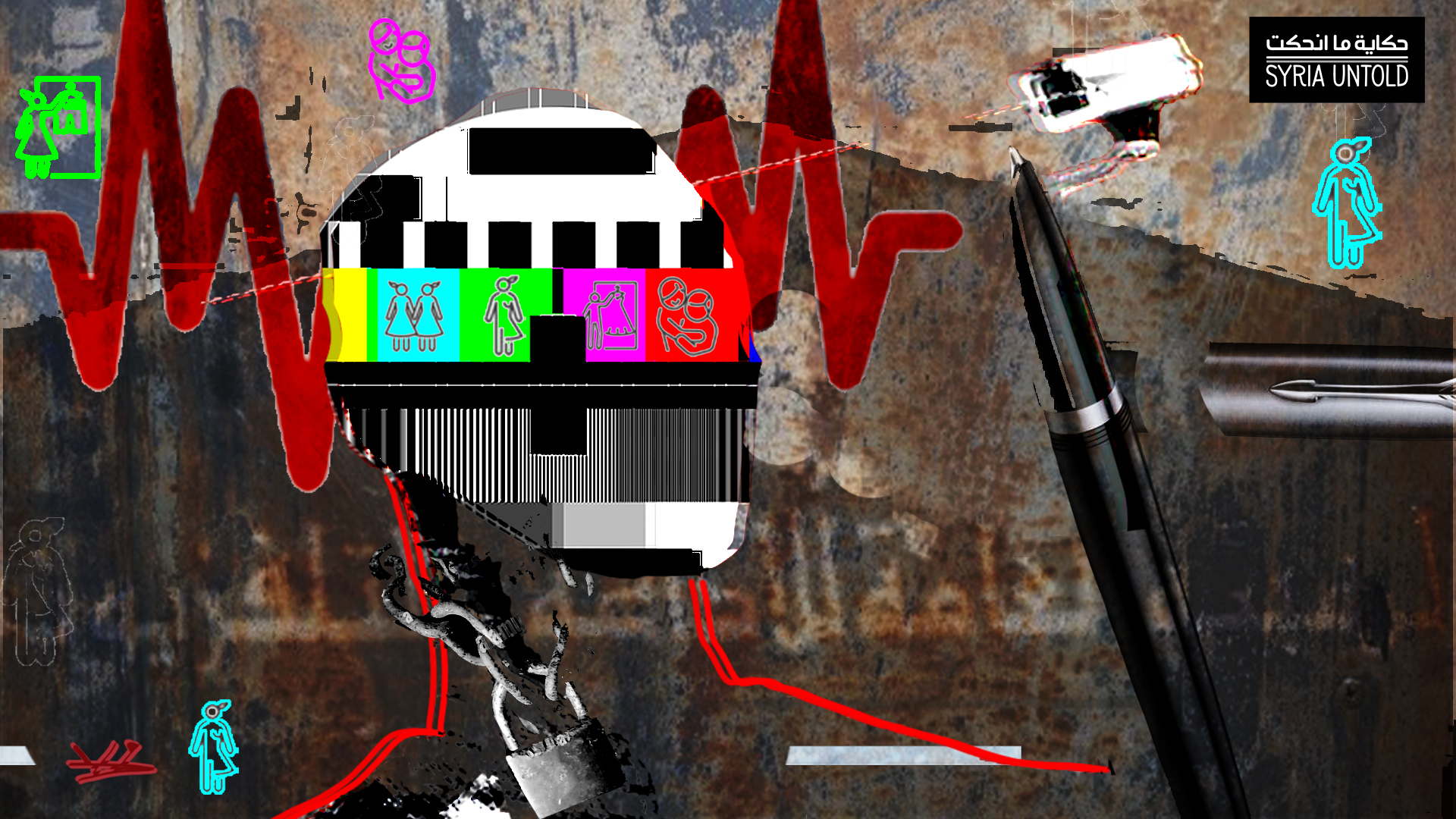

This article is part of the second round of our series on LGBTIQ Syria, published and commissioned by guest editor Fadi Saleh. Read this article in Arabic here.

LGBTIQ people, Syrian or not, have always felt a strong connection to visual pop culture. This was especially true in the 1990s and 2000s, when the Internet was not yet widespread. Our only refuge to fill our free time and escape our oppressive and heteronormative surroundings was television.

In every TV drama, film or song, I always managed to find someone who “represented” me, regardless of whether this character was queer or not. However, I would get ecstatic every time an actual queer character appeared on TV, even if that representation was negative. I was still happy to see acknowledgment that queers exist and are not completely erased.

In Syrian TV dramas, which were our pop culture as Syrians—especially with less pop music production compared to Lebanon or Egypt—there were a considerable number of queer characters that appeared every now and then. Here I try to highlight some of those characters that might have faded into oblivion, and I shed a queer light on the golden age of Syrian TV drama with which I grew up.

Bab al-Hara (The Neighborhood’s Gate)

This is probably—and unfortunately—the most famous Syrian TV series ever. And I say unfortunately because this show represents and celebrates heternormativity and toxic masculinity in its worst forms.

We do know that same-sex love or romance indeed happened during the time in which the series is set (Damascus of the 1920s) and probably way more often than we could imagine. But because the vocabulary we have now did not exist back then, most of that love and romance went without being directly named.

So here I wanted to re-imagine Bab Al-Hara as Bab Al-Hobb (Love’s Gate), in a radically different departure from how the actual TV show was made. I mean, in a Damascene environment where men spend this much time together separated from women, nothing ever really happened among people from the same gender, or among the queer characters?

Nidal, Ashwak Na’ima (Soft Thorns)

Nidal’s character in Ashwak Na’ima, a 2005 drama, is someone who I felt was queer from the moment I set eyes on her. She was one of my favorite characters, and of course I wished for a different ending than the one the show gave her. I would have preferred if she was allowed to remain a gender non-conforming character and if the series represented her difference as something positive until the end—one does not have to change in order to conform or be accepted or loved. At the end of the series, Nidal becomes like the other girls, heterosexual and conforming in her gender identity and expression.

Nonetheless, this ending does not have to overshadow the complex and sometimes beautiful representation of Nidal throughout the entire show. For example, her name, Nidal, is a gender-neutral name, and it suits a gender non-conforming character who is fighting and resisting a society that is not accepting of her (Nidal is Arabic for “struggle” and “fight”). Moreover, Nidal is a queer character par excellence, as she goes from being gender non-conforming to wanting to transition later on. All of these topics were represented in a bold way, at a time when representing such issues was quite difficult.

One of the most beautiful moments in the series is when Nidal’s father is called into her school in order to be informed about his daughter’s “queer” behavior. The father tells them: My daughter is here to learn, not to be told how to behave or act. He is very supportive of her, and the entire series contains many implicit positive messages, except for the ending, which shows us that her falling in love with a man made her “natural” again. Perhaps it is an ending that was written to appease the majority of Syrian viewers.

Fulla and Sa’do, Bok’at Daw (Spotlight)

Fulla and Sa’do is a sketch from the famous 2004 series Spotlight, and one that specifically lingered in my memory for years. Sa’do is a very queer character, played by actor Qusai Khouli. He is a feminine man with long hair who works at a night club. Despite the comedic framing, it was important for me to see that his representation was not negative all throughout the piece. At one point in the sketch, Sa’do flirts with the men who enter the club, and they do not react in a negative way. To me, just his being on the screen in a comedy series, where everyone is represented in a funny way, made me feel that we are not always laughing at him as a character, but also with him.

It is never mentioned explicitly whether Sa’do is gay or not, but he is clearly non-normative. It is important that such characters are represented and seen on every TV screen in our societies. Despite the comedic framing, it is still crucial to send a message that we exist in every walk of life.

Of course, in the sketch there is an association drawn between queer people and women who work at night clubs. Though this representation was probably intended to represent queers in a way that Syrian society finds “negative,” it is important to remind ourselves that both of them—the queer and the women who work at night clubs—are also part of society and oppressed minorities. So we should stop ourselves from finding every representation to be just “negative” and indirectly distance ourselves from queers and night club workers. Maybe we should start critiquing the negative intentions behind some representations, if we see any, instead of always assuming that portrayals of a queer sex worker or a queer who works at night clubs in Syria are always negative!

Abu Janti and the “tante”

I recently recalled a scene from the 2010 series Abu Janti during a conversation I had with a friend. When I re-watched the scene between the character Abu Janti and the “tante” (effeminate man), I remembered how such situations happened to us all the time and how common it was that in Damascus or other cities in the MENA region that two guys would flirt during a taxi ride. There was some flirting and joking around and some sexual innuendos from the tante’s side.

In my drawing, I am imagining the two characters actively flirting with one another, willingly and not just in a sarcastic manner as the taxi driver is represented in the TV series. I fantasize about them having a love story in the end.

I titled this illustration “Abu Janti and the Dandy” because dandy rhymes better here, and as an older English word, it refers to men who pay attention to their looks and the way they dress, and it could refer to queer or non-queer men. Either way, the way they are devoted to their style confuses especially those who associate looks and style with a specific sexual orientation. I felt that it is easier on the ears than “tante,” a word that has become a slur against queers and gender non-conforming men in our societies. This is what we have been taught since childhood about this word, though we have been working to change that and reclaim the word, to give it a more positive and political sense, so that someday it can become a normal word, devoid of any negative connotations.

I hope that we continue to work on queer issues in Syria and affirm our presence TV and in all aspects of Syrian life. Because simply, we exist in all fields and walks of life. Thanks to a history of oppression, we are constantly erased and made invisible. It is, therefore, vital to keep talking about queer issues and for us as queer artists to search in the farthest corners of popular culture for representations of queerness and transness—representations that emerged even before we realized we were LGBTIQ.