This article was first published on Orient XXI.

Italy is the first country in the European Union (EU), the Group of 7 alliance (G7), and NATO to appoint a diplomatic ambassador to Damsacus since 2012, meanwhile relations between Syria and the Arab League had been mending for some time. On 7 May 2023, in fact, Syria had been readmitted to the League, as desired by the 22 members, although not all of them were initially of the same opinion. Pushing hardest for Damascus' return to the negotiating table was Saudi Arabia.

Foreign Minister Farhan al Saud's visit to Syria on 18 April 2023, after ten years of frost, marked the first step in a historic rapprochement. Gradually all Arab countries resumed dialogue with Bashar al Assad, including Qatar, which was among the most hostile to the reopening of negotiations, emphasising the urgency of ending the civil war and countering the expansion of drug trafficking.

The normalisation process accelerated after the 6 February 2023 earthquake that struck north-west Syria and southern Turkey, claiming thousands of victims, including Syrian refugees and displaced persons. The urgency of humanitarian aid and relief management prompted the Arab chancelleries and Ankara to reopen windows of dialogue with the Damascus regime instead of involving other actors.

International Strategies

For Italy, Syria is not a major economic partner, as Damascus accounts for only 0.2% of Italy's entire trade. Rather, the interests lie in political and strategic gains. In fact, one of the motivations pushing Italy to speed up with the resumption of bilateral relations with Syria is the current government's desire to push the West to once again play a leading role in the Middle East, and not leave the field open to Russia, Iran, and Turkey. The closure of European and American embassies and the economic sanctions imposed on the Damascus regime have in fact further facilitated the rise of Russian influence in the Middle Eastern country. Syria and Russia have had strong relations, political and economic, since the time of Assad the father, Hafiz Al-Assad.

A Previously Unpublished Interview with Father Paolo

26 August 2022

The country ruled by Putin remains the main supplier of arms to Syria. For years Russia has leased its naval bases in Tartus and Latakia, providing Moscow with an outlet in the heart of the Mediterranean. Moreover, Russian mediation to foster a rapprochement between Damascus and Ankara is seen as a further cause of Western weakening in the area. In addition,according to Russian Defence Ministry figures, Moscow has deployed over 63,000 troops in Syria since 2015, solidifying their military presence in the region. Moscow is said to be responsible for more than 80% of military supplies to Damascus, according to research by Sipri- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

In addition to strategic reasons, there would also be ‘humanitarian’ reasons. According to Tajani, Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs, “we need to understand what to do in order not to leave the Russians and others a monopoly on the situation”. Tajani added that “the biggest refugee crisis in the world originates in Syria, we inevitably feel these effects far beyond the Middle East, even in Italy and the rest of Europe: we must therefore update the European Union's approach, adapt to the evolving situation, and that is why I have called for greater EU attention to Syria”. Before the peaceful popular revolution in March 2011, which was followed by the bloody repression by the Damascus regime, there were just over 23 million inhabitants living in Syria.

Today, according to UN data, about 7.5 million Syrians are internally displaced and an equal number live outside Syria as refugees. Practically only one in three Syrians still live in their homes. Much of the country is devastated, with entire residential neighbourhoods, hospitals, schools and archaeological sites destroyed by bombing. According to the same source, more than 90% of Syrians are in need of humanitarian aid. The collapse of the Syrian lira (the dollar-lira exchange rate is 1 to 13.001) has further penalised the local economy, already so scarred by years of crisis and destruction.

“After 13 years, we need to update the EU's approach and adapt it to the evolving situation,” said Antonio Tajani.

“Our goal is a more pragmatic and proactive policy to increase the effectiveness of our humanitarian assistance and to create the conditions for the safe, voluntary and dignified return of Syrian refugees (...) in compliance with UNHCR standards. No compromises on democracy, inclusion, fundamental freedoms and human rights; no one wants to forget the Assad regime's very serious responsibilities towards its people nor its closeness to countries hostile to us, but precisely for this reason we must re-launch a dialogue with the rulers in Damascus and with the opposition by supporting the efforts of the UN Special Envoy, Geir O. Pedersen.”

Relations between Rome and Damascus have undergone some changes over time. In August 2011, a few months after the start of the Syrian government's violent repression against civilians in the streets, Foreign Minister Franco Frattini recalled Italian Ambassador Achille Amerio to Damascus, inviting other European chancelleries to take similar initiatives.

Relations between Rome and Damascus have undergone some changes over time. In August 2011, a few months after the start of the Syrian government's violent repression against civilians in the streets, Foreign Minister Franco Frattini recalled Italian Ambassador Achille Amerio to Damascus, inviting other European chancelleries to take similar initiatives.

In February 2013, the Syrian embassy in Rome was closed and the diplomatic staff returned home. However, over time there have been significant signs of proximity and support from certain Italian political circles with respect to the regime in Damascus. On the one hand extreme right-wing forces, on the other extreme left-wing forces. The so-called ‘rossobruni’, divided on many domestic political issues, agreed to support Assad in an anti-imperialist and anti-Islamic function at the same time.

Several far-right political delegations have been received in Damascus over the years, but the most significant affair remains that of the 2018 visit of Ali Mamluk, head of the National Security Council in Syria and head of intelligence from 2005 to 2012, to Rome. At the invitation of then Interior Minister Marco Minniti and intelligence chief Alberto Manenti, Mamluk had arrived in the capital in total defiance of the European Union sanctions against him.

At the time, several NGOs had asked the European Union to launch an investigation to understand why a leading figure of the Damascus regime, under investigation for crimes against humanity, had been able to pay an undisturbed visit to Italy.

These attitudes, now culminating in the decision to send an ambassador back to Italy, generate a huge contrast between Western allies.

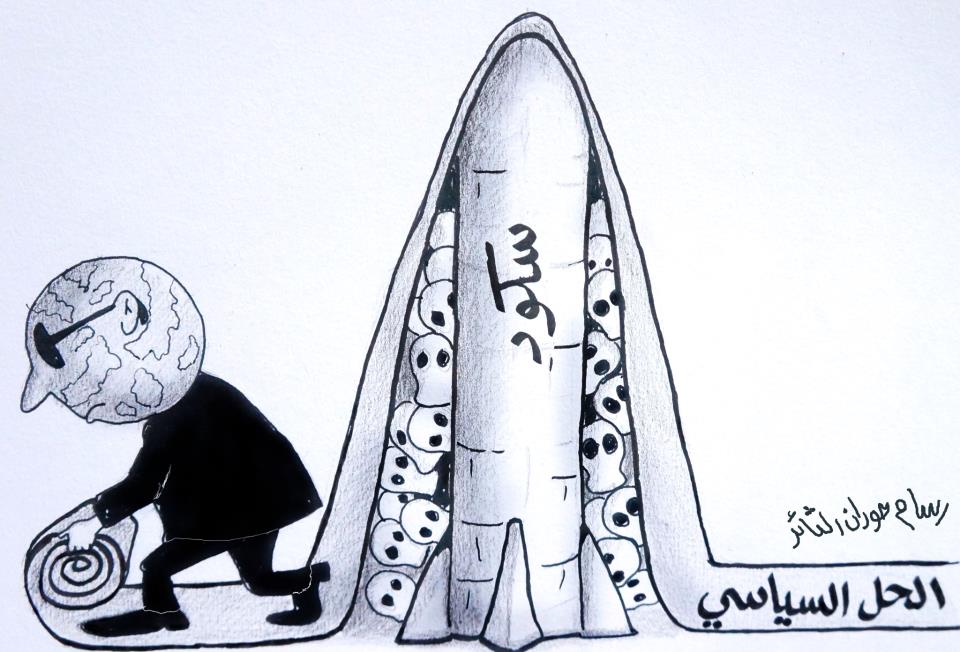

Since 2011, Syria has been subject to sanctions by both the European Union, renewed until 2025, and the United States. In 2020, the Trump administration promoted the Caesar Act, which sanctioned the Damascus government, including Assad himself, and introduced measures against individuals and companies that support him economically. In April of this year, US President Joe Biden signed the Illicit Captagon Trafficking Suppression Act, a document against the production and trafficking of Captagon - known as ‘poor man's cocaine’, an addictive drug similar to amphetamine that is produced and purchased cheaply with low-quality pills - from Syria. The document provides for new sanctions against individuals, entities and networks affiliated with Syrian President Bashar Al Assad's regime that produce and traffic Captagon and follows the Captagon Act already signed by Congress in 2022.

On 14 November, France issued an international arrest warrant against Bashar al Assad, his brother Maher and two other Damascus government officials on charges of being responsible for the chemical weapons attack in August 2013.

On 14 November, France issued an international arrest warrant against Bashar al Assad, his brother Maher and two other Damascus government officials on charges of being responsible for the chemical weapons attack in August 2013. A piece of news that should have caused a sensation, but which went unnoticed. The criminal investigation by the Specialised Unit for Crimes against Humanity of the Paris Judicial Court determined Assad to be responsible, although the latter denies any involvement. In October 2023, the International Court of Justice in The Hague started a trial for war crimes committed in Syria since at least 2011, although Syria did not appear at the trial.

The Desaparecidos

The crisis of Syrian refugees and displaced persons now seems to have calcified and is no longer addressed, regionally and internationally, as an emergency. In fact, after the interlude of the 2022 earthquake, Syria has once again disappeared from the agenda of international diplomacy and in this context, the Italian initiative to resume relations with Damascus is even more controversial.

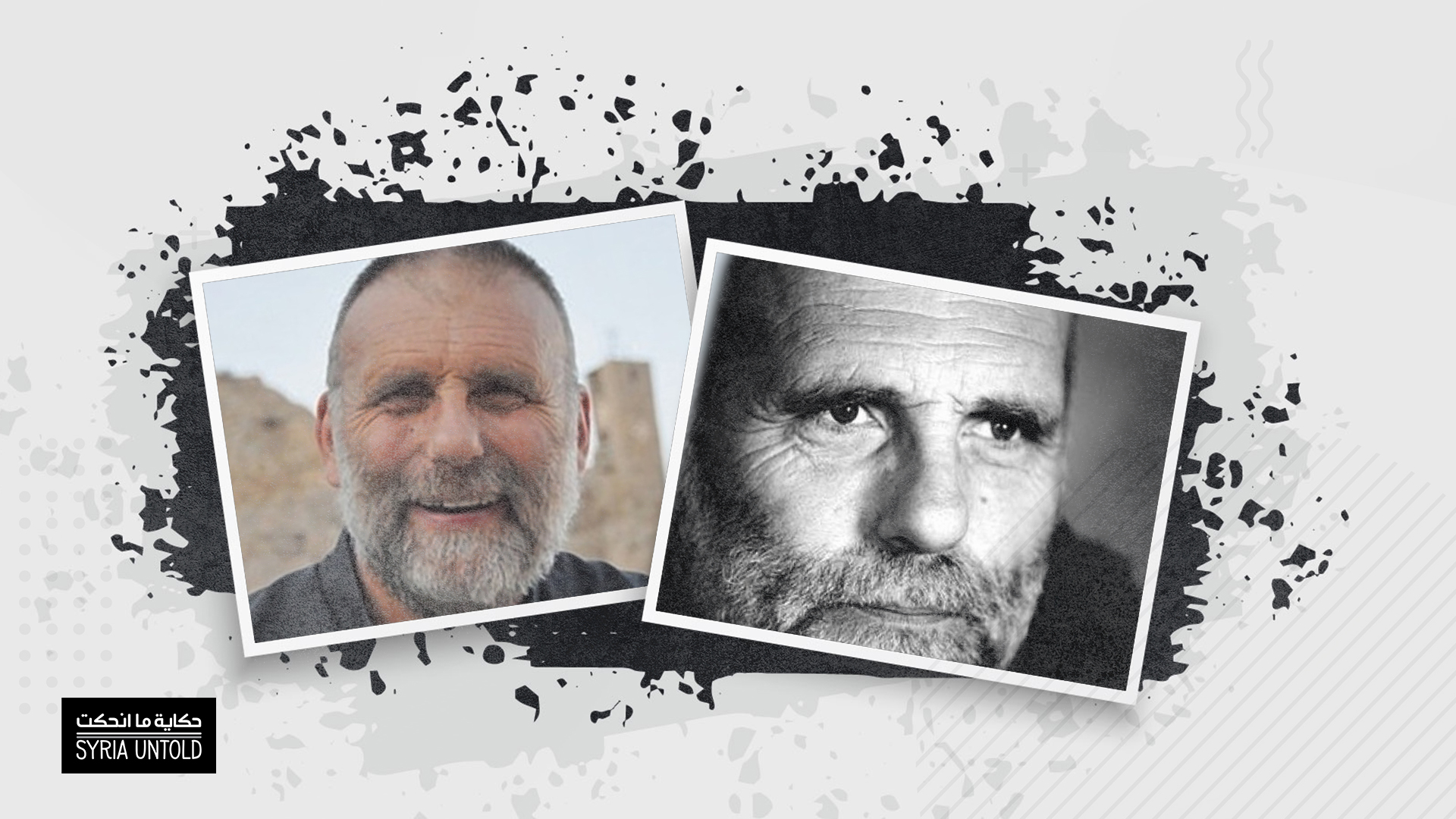

Among the many reasons that should prompt reflection on the advisability of normalisation between Rome and Damascus is the story of the disappearance of Father Paolo Dall'Oglio, the Roman Jesuit who disappeared in Syria in July 2013. Eleven years later, there is no truth about the fate of the cleric and there has never been any sign of cooperation from the Syrian government to shed light on this story. Father Paul may have been kidnapped by ISIS, according to the most accredited hypotheses, but there is no official confirmation.

Among the many reasons that should prompt reflection on the advisability of normalisation between Rome and Damascus is the story of the disappearance of Father Paolo Dall'Oglio, the Roman Jesuit who disappeared in Syria in July 2013.

In October 2022, the Rome Public Prosecutor's Office had asked for the investigation to be archived, stating that it was ‘impossible to tell if he was still alive’. Abuna, which in Arabic means our father, as Paolo dall'Oglio is still called by those who have not lost hope of seeing him alive again, has thus become one of the thousands of Syrian mafqudin, desaparecidos, disappeared.

A forced disappearance in Raqqa, and the empty spaces left behind

09 December 2020

It is estimated that there are more than 150,000 women, men and children who have disappeared without a trace. Many families of Syrian exiles continue to press for clarity about the fate of their relatives, but except in the case of people with dual citizenship, there is hardly any feedback. Most of the Mafqudin have disappeared after being stopped at checkpoints and taken to government prisons, but even among Syrians who have been repatriated voluntarily or by force, cases of disappearances are multiplying.

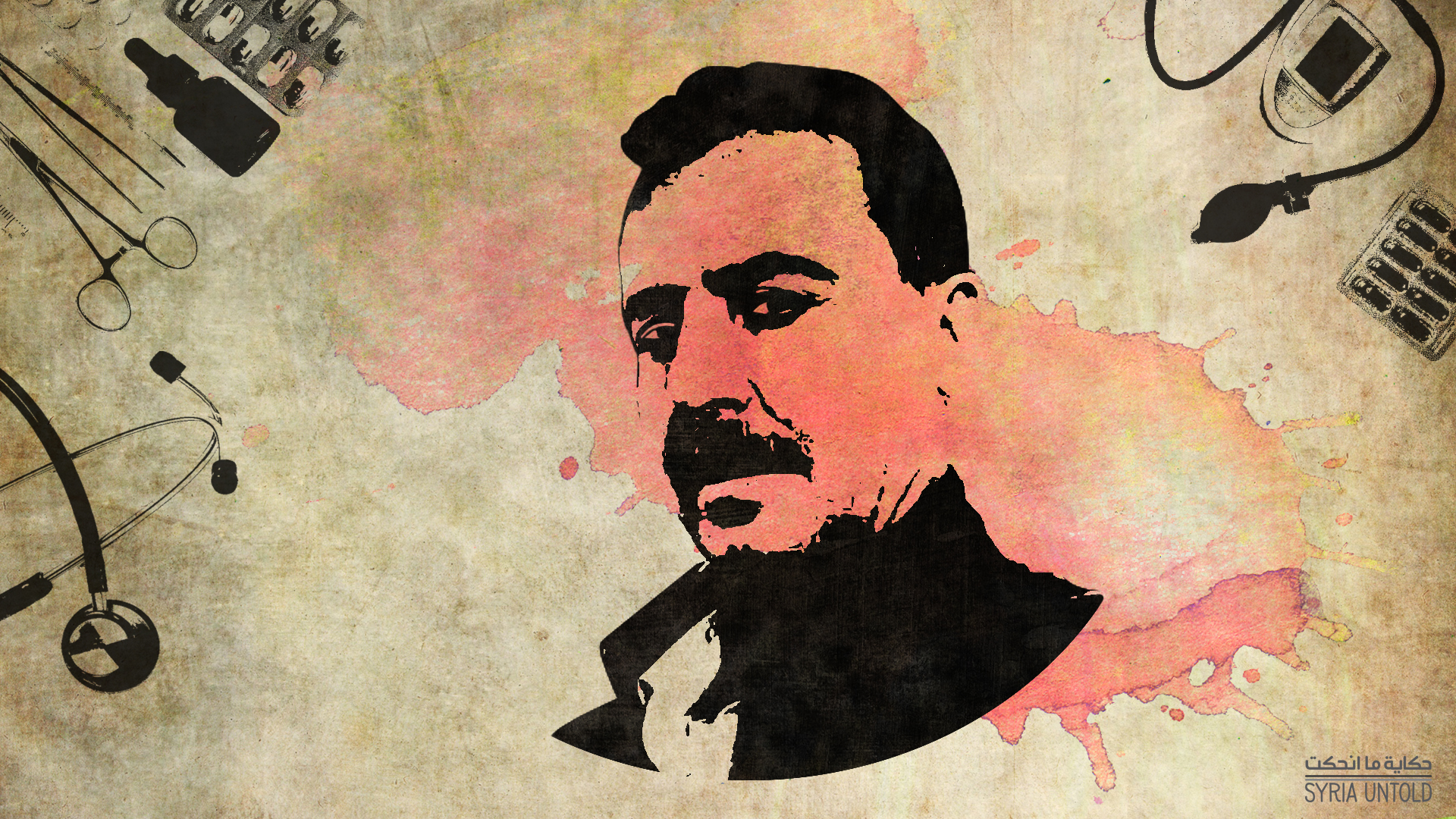

One of the best-known stories is certainly that of Mazen al Hamada, a former prisoner in Syrian jails, tortured and humiliated as he himself denounced during some of his speeches in the West, acting as spokesman for Syrian political prisoners. Al Hamada voluntarily returned to Syria in 2020, tired of hearing promises that were never kept and of seeing the immobility of international chancelleries. Nothing has been heard of him since then.

One therefore wonders whether the Dall'Oglio dossier will be on the new ambassador's desk and what priority will be given to it, just as it will be crucial to understand if and how the issue of human rights will be addressed, also with reference to the return of possible Syrian refugees to the motherland.