On the flight from Doha to Damascus, the tension was palpable. You could hear it before you saw it — the sniffles, the sudden exhales. As the plane descended, the tears came like muscle memory.

At immigration, strangers turned to each other and asked: “How many years has it been?” I said twelve. A family from Hama answered: “Forty.”

It hit me — exile isn’t just about time. It’s about what you return to, and what’s no longer there.

Friends were waiting for me at the airport — one of the few places in Damascus I’d never really known. I had only been there twice before: once to say goodbye to a friend, and once to my sister. Like most Syrians, I didn’t leave the country through the airport, but through the narrow and uncertain paths of smuggling routes.

Still, Damascus returned to me quickly — or maybe I returned to it. Within hours, it felt like the twelve years away had collapsed into yesterday.

Two years earlier, I had visited Palestine — my first homeland — for the first time in my life. I was the first in my family to do so. I expected that landing in Damascus would stir the same emotions. But it didn’t. Not exactly.

In Palestine, I walked as if floating — a meter above the ground, carried by memory, history, and the unspoken weight of generations. I felt like I was walking for all the Palestinian-Syrians I know who still cannot go.

Damascus, by contrast, felt heavier. Grounded. As if every step sank a meter into the earth. It was no less emotional — but it was closer to grief than wonder.

At al-Yarmouk

On my second day, I went to Al-Yarmouk, — the neighborhood where I grew up. I had lived there for 18 years, until my family moved to Mashrou’ Dummar. That move was more difficult than leaving Syria altogether. It wasn’t just a change of address; it was a cultural and identity shift.

Back then, we were afraid of losing something deeper. Of course, we were still Palestinian, but Al-Yarmouk was a daily reminder of what had already been lost. It was a place where politics lived in the streets — not just in conversation, but on the walls. Posters of Palestinian factions were everywhere, whether you agreed with them or not. Arafat watched over the camp like a grandfather you didn’t always understand but couldn’t ignore.

Being Palestinian was — and remains — a political identity more than anything else. It is shaped by memory, displacement, and resistance. Being Syrian was different — not apolitical, but far more constrained. That was part of the struggle: the tension between a politicized Palestinian identity and a Syrian one that had been politically silenced for decades. That silence cracked in March 2011, when the Syrian revolution began.

After we moved, Al-Yarmouk became more like a village we visited on weekends. We’d gather friends in my family’s now-empty house. Politics and football dominated every conversation. Assad was rarely mentioned — and when he was, it was with bitterness.

Al-Yarmouk had its own rhythm, its own identity inside Damascus. You didn’t see Assad’s face on the walls — not the father, not the son. Even Palestinian figures loyal to him were considered outsiders. The camp had carved out its own emotional and political sovereignty.

For me — and for many other Palestinians — the revolution was a spark in our Syrian identity. As a new political Syrian identity was taking shape, it became easier to call ourselves Syrians. We were no longer just guests or outsiders. We were part of the struggle for dignity and freedom.

For our part, Al-Yarmouk welcomed displaced Syrians into its schools. At the time, I was working at Al-Basel Hospital, a Palestinian-run charity hospital offering medical aid. It was far from enough to meet the needs of those injured and bombarded by the regime, but we did our best to treat patients from Hajjar al-Aswad, Tadamun, and other neighborhoods that had taken refuge in the camp.

Even though it sometimes felt life-threatening, we never hesitated. My brave colleagues and I never thought about the fact that we were Palestinians and could have stayed silent. We simply did what needed to be done.

It hit me — exile isn’t just about time. It’s about what you return to, and what’s no longer there.

But the price Al-Yarmouk paid was high. The destruction was systematic. Homes, schools, graveyards — nothing was spared.

I don’t know if you’ve seen Black Mirror, the series about how technology distorts memory and identity. In one episode, a man has a chip implanted in his brain that lets him relive his memories — watching his past with the clarity of a screen. He sees himself dancing with an ex-girlfriend, laughing, flirting, as if it were happening again.

Standing in Al-Yarmouk, I wished I had that chip. not to relive the past, but just to recognize it.

I spent most of my life on these streets — twenty three yeras — and yet I couldn’t remember what they looked like. The shock hit hardest when I asked someone where Palestine Hospital was, a landmark I thought I’d never forget. They pointed to the building right next to us.

Syrians of the Golan Heights: A Year of "Artificial Calm" in the Geography of the Forgotten Occupation

21 October 2024

A wave of shame and sadness moved through me. How could I not recognize the street I grew up on?

Our neighbor had once painted his building with red cement. It was how we recognized our building among the identical gray blocks.

The building — open, hollow, gutted from every side — looked like a broken mouth.

The strangest part was the view from my parents’ balcony. It used to face another building just meters away. Now, with most of the block destroyed, it opened into a landscape I had never seen before. A panoramic view — a "gift" of Assad’s destruction.

The Politics beneath the Rubble

The story of Palestinian-Syrians can’t be told without acknowledging how the Assad regime used Palestine as a political tool.

Under Hafez al-Assad, slogans like “Liberating Palestine” became state doctrine. But behind the rhetoric were actions that deeply harmed the Palestinian cause. We have the clearest example in 1976, Assad supported right-wing Lebanese militias in overrunning the Tal al-Zaatar refugee camp near Beirut, leading to the massacre of more than 1,500 Palestinians.

Damascus, by contrast, felt heavier. Grounded. As if every step sank a meter into the earth.

The regime also reshaped Palestinian refugee life in Syria. After Black September in 1970, units of the Palestine Liberation Army were absorbed into the Syrian military. Palestinian men were conscripted — not to fight Israel, but to protect the regime.

Later, Assad backed factions that split Fatah and weakened the PLO. Loyalty to Fatah and Arafat could land you years in prison. Through the infamous Palestine Branch of military intelligence, the regime monitored, divided, and controlled Palestinian organizations across Syria and Lebanon.

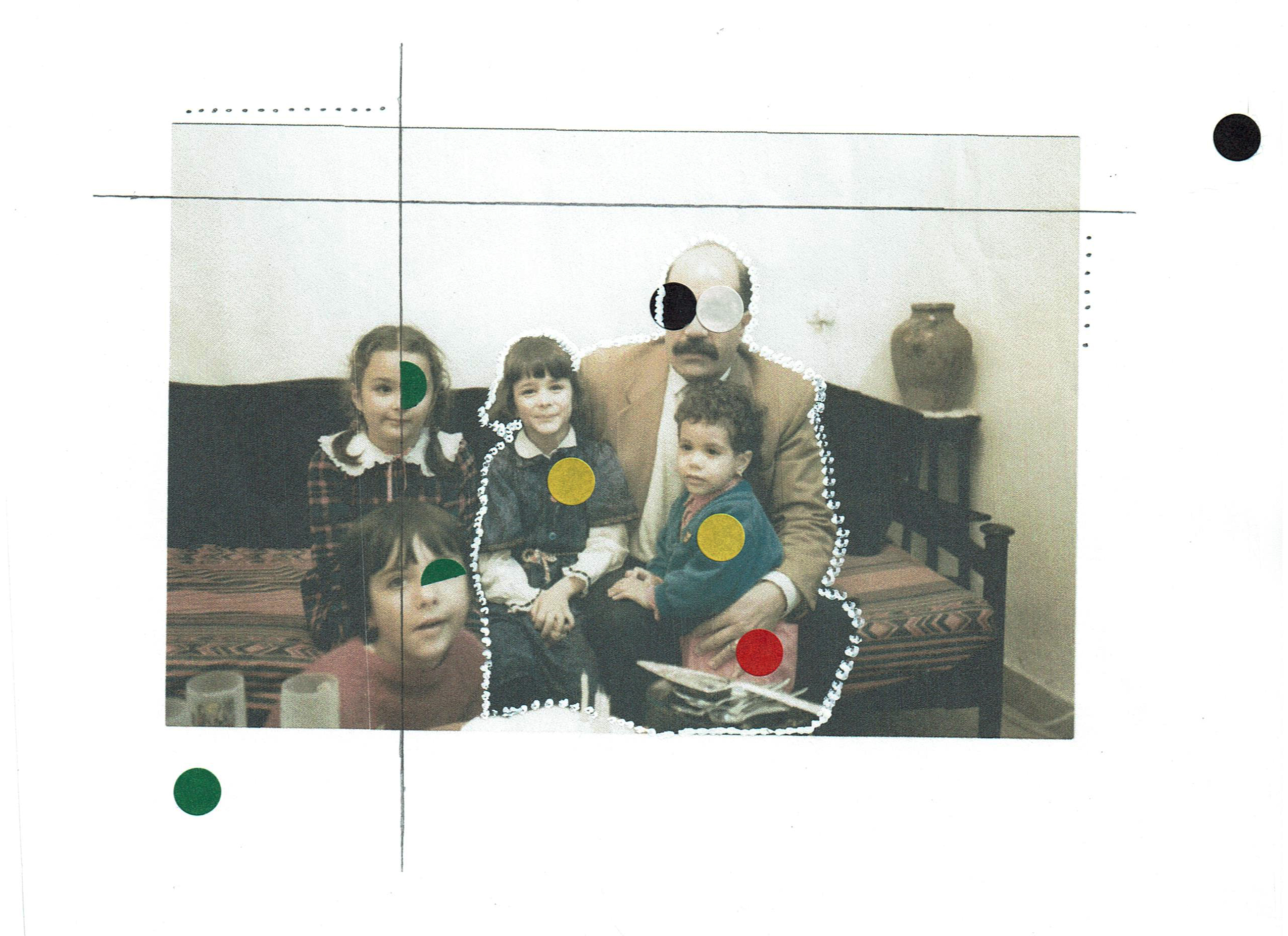

Where is my father?

25 April 2022

In Al-Yarmouk, regime-aligned factions built parallel systems — schools, clinics, daycare centers — each tied to a political affiliation. Still, the regime couldn’t claim the hearts of the people. Those connected to these structures were often seen as mukhabarat or regime puppets.

That began to change slightly with the rise of Hamas. When Hamas moved its leadership to Syria in the late 1990s, it was welcomed, supported, and given space to operate. As it gained popularity, some began to see Assad as part of the resistance. Backed by Iran, it trained fighters from across the region in Syrian camps.

Still, Al-Yarmouk never endorsed Assad’s war on Syrians in 2011. That line, thankfully, wasn’t crossed. While Hamas’s rhetoric gave Assad a foothold in Palestinian discourse, it ultimately chose not to join the war like Hezbollah did. That decision had many reasons, which deserve deeper reflection.

The so-called Axis of Resistance began to fracture in 2011, when Hamas sided with the Syrian uprising. Assad responded by cracking down on Hamas-aligned communities and empowering again his loyalist Palestinian factions — some of which even shelled Palestinian neighborhoods like Al-Yarmouk.

Who Are We Now?

The collapse of the regime in 2024 marked the end of an era. Syria no longer seems to be a rhetorical battlefield for others’ causes — a place where Palestine was invoked, but never truly defended.

For Palestinian-Syrians, this has opened a space for reflection. The camp — once a site of memory and resistance — is now often just a ruin, or an exile within an exile. Most of us now live outside the camps, and many outside Syria altogether. A new generation is growing up in cities, far from the places that once shaped our identity.

This moment has become an opportunity to rethink who we are — beyond slogans and militarized belonging — and to reconsider our place in a region rapidly shifting toward peace accords: agreements that are fundamentally about us, yet made without us.

Today, the Palestinian-Syrian identity stands at a crossroads. Those still in Syria are often displaced from their original camps. Those abroad carry fragments of a fractured belonging.

I remember in 2011, when I criticized the regime, some people told me, “You don’t have the right to speak. You’re Palestinian.” It’s happening again now — whenever we express independent views on Syria’s future.

The crisis runs deep — and it has many layers. Not only has our rhetoric been co-opted by Assad, but increasingly by a global and regional majority that speaks on our behalf. We are being narrated by others — turned into symbols, stripped of complexity, placed at the intersection of crises we didn’t choose.

First: how do we separate the Palestinian-Syrian identity from the ideologies of those who claim to speak for Palestine? We should not be held responsible for the positions of groups like Hezbollah or Iran — both of whom have committed grave crimes against Syrians.

Second: how do we preserve Palestinian identity outside the camps, in this “new” Syria? I appreciate it when people say, “You guys are Syrian.” I love that — I feel Syrian. But being Palestinian still matters. It carries memory: of the Nakba, of Galilee, of where we come from.

Gate of the Sun: A Gate to Memory and Another to Love

03 June 2024

Third: some Palestinians still believe in the so-called Axis of Resistance. Among them, a kind of blood-based Palestinian exceptionalism blinds them to the suffering of others — to Syrians and Lebanese who endured Assad and Hezbollah. These voices flood social media, branding Syrians as traitors, painting the revolution as a NATO conspiracy. This rhetoric has done lasting harm to the Palestinian-Syrian cause.

Fourth: how do we speak to Arab audiences — especially Syrians? For decades, regimes co-opted the Palestinian cause into their propaganda. I’m reminded of what Edward Said once said: “Much of our cause had to work with the Western mind.” But in 2025, I see that much of the work lies with the Arab and Syrian mind. Being understood within the region — truly and fully — requires real effort from our side.

Fifth, and finally: how do we assert our Syrian identity when it’s constantly denied? I remember in 2011, when I criticized the regime, some people told me, “You don’t have the right to speak. You’re Palestinian.” It’s happening again now — whenever we express independent views on Syria’s future.

This reminded me of a conversation I had in Norway, after a local newspaper ran an article about my visit to Al-Yarmouk, titled “The Bergenser Returns to His Childhood Home.”

I told a friend, “No, I’m a Palestinian-Syrian. But I’m happy they called me that.”

He replied: “You work here. You have a home here. You contribute to this city. You’re a Bergenser. Deal with it.”

It was the exact opposite of those who want to erase my Syrian identity.

So I ask them: If having a home in Bergen makes me a Bergenser — Can having a destroyed home in Syria still make me Syrian?