Jihan K nurtures the seeds of the fractured relationship with her father by browsing into family’s photo albums and watching old videos, in her debut film "My Father and Gaddafi”. Screened at the 82th edition of Venice annual Film Festival (27 August- 6 September 2025), the documentary was shown at the ‘Out of Competition’ section of the international venue, in a country with a colonial past in Libya.

The Libyan-American filmmaker struggles to feel his father was a real person, not just a symbol, in their home and on the national stage.

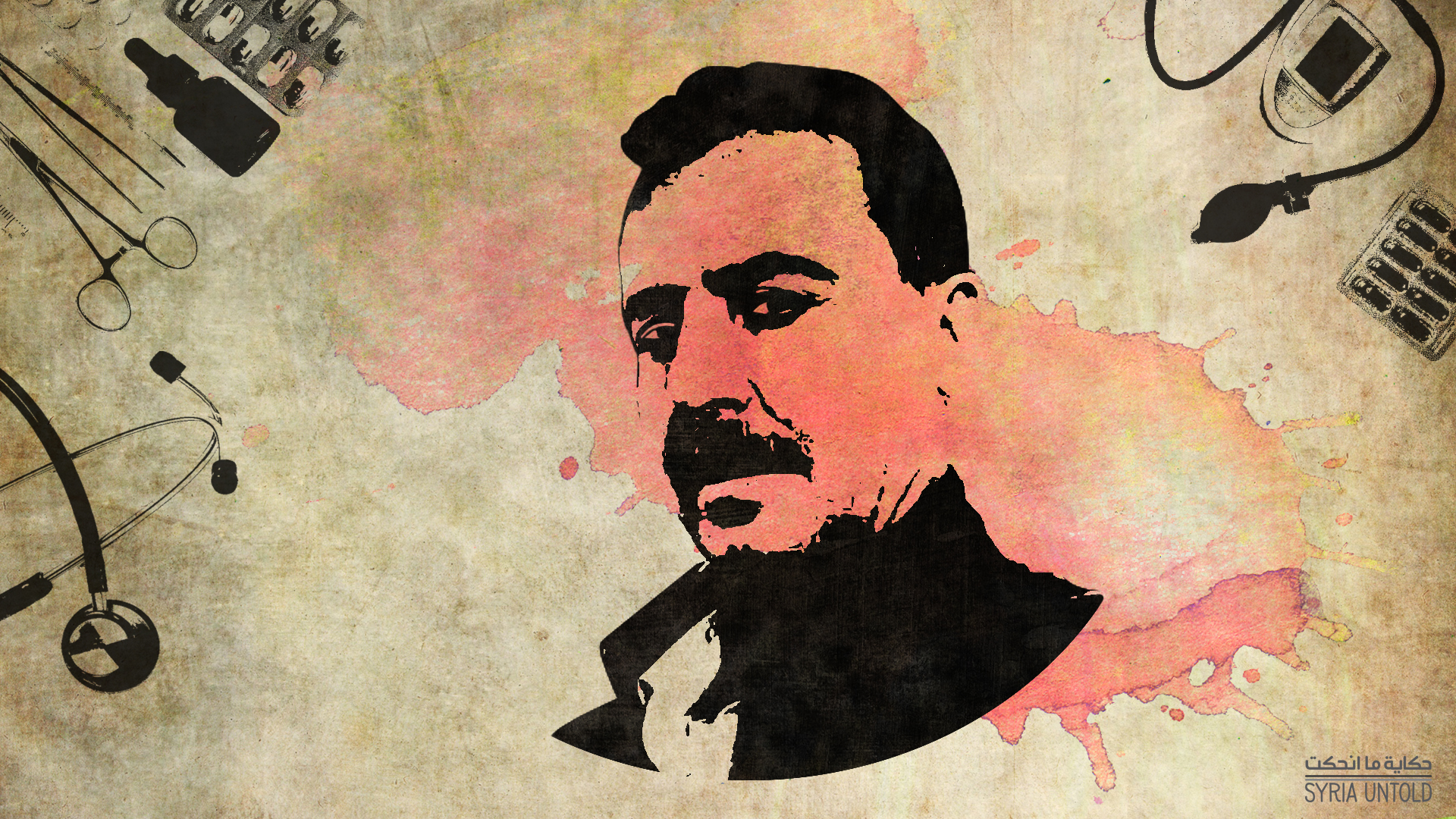

Like many documentary filmmakers from the Arab region in their debut work, she returns to her family and opens her notebooks. The memories she delves into are centered around her father, human rights activist Mansour Rashid Kikhia, Libya's former foreign minister and ambassador to the United Nations. After defecting in the early 1980s in protest against the colonel's bloody regime, Kikhia was exiled by Gaddafi and became an opposition leader and a human rights defender.

With Mansour's rise as a potential alternative leader after the American military attack on Gaddafi's Libya, the Libyan dictator forcibly disappeared him in 1993 at a hotel in Cairo, where he was visiting to attend a human rights conference.

Jihan attempts to say many things at once, primarily trying to address her missed relationship with her father who has been missing since she was six years old. She paints a vivid image of him, through photographs, videos and family testimonies.

Archival footage was not the only source. Interviews with Mansour Kikhia's family and friends helped Jihan portray her father as an honest politician who paid with his life for his national ambitions, although being aware of the dangers of being singled out. She touches on his refusal to collude with the West, despite his move to the opposition, his insistence on peacefulness, and his call for democracy. His goal was not necessarily to topple the Green revolution leader but rather to attempt exerting internal and external pressure on him, perhaps to change him slightly.

Yet, at the heart of the film is Jihan's mother, Bahaa Al-Omari, who recounts the story of her family in Damascus. Her father was detained there for years when she was a child, then she moved as a young woman to New York, and finally she married Mansour. The then-disappeared Libyan politician accepted to be the third person in her life, after her daughters from the first marriage. After his defection, they went to live in France.

Bahaa tells the details of her final farewell to Mansour, before leaving for Cairo, saying ‘There are many reasons, but only one death.’ She then had to play the role of father in her husband's absence, leading an international search campaign, fuelled by resilience. The case was raised on Arab and foreign channels thanks to her request that his fate be revealed, soon expressing her loss of faith in democracy and human rights when Mansour's disappearance was normalised.

In desperate attempts to cling to what remains of her hopes of saving her husband's life, Bahaa records a video in which Jihan demands Gaddafi to release him. Then the Syrian woman finds herself clinging to the 3% CIA- revealed chance that the news of her husband Mansour's death is false.

In a breathtaking scene, Bahaa recounts how she was forced to go to the Libyan desert and meet Gaddafi in his tent, to look into the eyes of the man who caused the tragedy, negotiating cautiously, fearing for her life, in the hope that she could persuade him to release her husband.

He plays her Syrian music, trying to impress her. When he talks about the ‘strength of Damascene women’, she confirms that this has historically been the case: when the father is absent, she takes the place and becomes a sword. ‘You are talking to a sword.’ Gaddafi finally pretended that he himself did not know Mansour's fate, but that in his ‘daydreams’ he could imagine him alive. ‘I don't like to celebrate death,’ says Baha's mother when asked if she is happy that Gaddafi was killed in such a gruesome manner after the fall of his regime.

The director ends her film with a final chapter that uncover the truths about the family and how they dealt with the loss of their father after his body was found frozen near one of Gaddafi's palaces, before the country slipped back into civil war. Her brother finally got his ‘conclusion’ by touching his deceased father's hand, while Jihan was denied this for religious reasons. As for whether the nine-year-long filmmaking process constituted a fitting conclusion, Jihan makes us feel that this is indeed the case, at least in the final shot.

The director then wraps up all of the above with another narrative thread, covering Libya's history during Italian colonialism, through the monarchy, to the rise to power of the ‘Bedouin’ Gaddafi.

This is a film about another Syrian mother whose partner was forcibly taken away, but this time by another dictator. Accompanying the mother throughout much of the film raises the question of whether the documentary film industry encourages those wishing to make their first documentary to adopt it as a journey of self-discovery, and whether it would have been possible to make a film from the perspective of the mother, Baha, in this case.

Jihan's attempts to add an investigative and exciting tone do not seem convincing here. Despite reviewing the circumstances surrounding her father Mansour's disappearance and her mother's efforts to find him over two decades, we later learn that she began working on the film in 2016, years after her father's body was found and buried, shortly after Gaddafi's fall. In other words, the reconstruction of the search preceded the work on the film. The interviews she recorded with family members and a former lawyer for Gaddafi did not reveal anything new, except perhaps to sketch a few additional details about Mansour's character.

Jihan presents the film as a last-minute attempt to preserve the memories of her ageing father Mansour and mother Bahaa, for fear that they will ‘go’ and take all those memories with them, at a time when young people are being killed in Libya ‘like drinking water,’ and layers of crimes are piling up. A dictator has died and a thousand dictators have emerged, the participants in the film said.

In press interviews, Jihan also talks about her attempt to ‘humanise’ Libya and its people, reconnect with her father and his country, and hold on to her Libyan identity. This explains her excessive use of, or rather flooding of, the film with numerous clips from home videos and family photos, which do not always serve their purpose.

The young director succeeds in presenting a captivating film with a coherent narrative that ties together all these intertwined threads—political, historical, and personal—with a few flaws that are understandable given her close relationship with the subject of her debut.