My Syrian friends often approach me to ask: "What do you think of this or that movie…of course we didn’t watch it, but you surely did!"

For me as a filmmaker, nothing is more frustrating than knowing that the most connected—nearly identical—audience for this cinema, able to understand its events and characters, time and place, is the last audience to have a chance to see it. Such a chance may arrive at best two or more years after a film's first release, and it will often be limited to a very narrow group, mostly personal friends of the filmmakers. And here, I will discuss the reasons why our audience is frustrated by this lack of accessibility.

This history of alienation goes back a long way. Since the 1960s, cinematic life was marginalized as a social act to near oblivion in Syria: there is barely anything left of it. Cinema was affected in terms of production and distribution, regardless of its genre (fiction, documentary and so on). It has undergone all the mechanisms of political despotism, like any other kind of art, whether visual or literary.

What little was achieved only saw the light because of the relentless resolve of the directors. This same dynamic may have resulted in a highly elitist viewership. But what happened after 2011 was a clear political division—at least in the first four years of the Syrian revolution, documentaries became a completely dissident art form, produced by filmmakers opposed to the regime; meanwhile fiction films either became pro-regime propaganda, or murmuring grey voices with a disconnected choice of topics that could seem almost surreal to a Syrian audience! Production of those films is absolutely monopolized by the National Film Organization.

"There is a war!" was always my first response to this alienation between audience and documentary. This was an alienation not intended by either of the two sides, but it really is war.

First of all, if we try to define the Syrian audience in general and absolute terms, it is the audience that will receive the film through Syrian platforms, which are divided into: Syrian film festivals, Syrian TV stations interested in producing and/or buying screening rights of documentary films, and commercial movie theaters with a strong interest in screening documentary films. Many secondary platforms will, of course, follow those three—for example, cultural centers or independent events may seek to program hosting documentaries.

In post-2011 Syria, there are no such platforms that will screen our films, despite them having reached the most prominent festivals and won prestigious awards. They are not films that exist within the category of cultural recognition and artistic creativity in Syria. For these platforms—if they exist—our films are entirely rejected political positions. In Syria, and the few platforms that currently exist within it, there is only room for fiction films, short or feature length, produced by the National Film Organisation or what little the censorship leaves available to the public.

So it's a war. That could be our overall answer to there being nothing we can call a "Syrian audience," especially when a judgment is passed as an absolute conclusion, that the Syrian audience loved this film or condemned that film.

What about Syrian audiences living in exile?

Yes, there's a Syrian audience that's passionate about this cinema all over the planet, and it is largely concentrated in Europe. There are two, at least culturally, vital cities—Berlin and Paris—where more platforms and opportunities for Syrian affairs exist; perhaps because of the concentration of Syrian institutions or because of the intensity of cultural and artistic activities in general.

Yes, there are film festivals in almost every city or even town across Europe, to which waves of Syrians have fled to escape death. But does this mean that Syrian documentaries actually reach this audience?

In my opinion, no—the majority of Syrians currently living in these cities have not yet considered the local or international film club or festival their platform, while attendance rates tend to still be very sporadic. We can't say that a few dozen Syrians attending a Syrian film here is evidence of the presence of a Syrian audience denouncing, promoting and engaging with these films.

This inevitably reflects back on the film product in it’s critical and appreciation prospects. The absence of a screening platform means that the audience is deprived of discussing with the filmmakers the film's content or artistic choices, and them expressing their opinions. It is our right to see Syria through the eyes of our Syrian peers and to open up the dramatic treatment to criticism and research.

It also reflects on the development of the themes of these films and their dramatic treatment styles. Several years after Syria's first documentary successes, our discussions as filmmakers have now turned to a purely western local audience, whose interests are often focused on a political understanding of the Syrian issue, of Syria as a "strategic" country, of Syrians as a human group.

This is a huge responsibility weighing on the directors, because every word in screening discussions leaves strong impressions and may be considered by part of the audience as a given fact. So how do we create the dramatic narrative out of our own tragedy to then share it with an audience that is perhaps furthest from that tragedy? Such questions have full legitimacy, and Syrians have the right to pose them to filmmakers.

In an attempt to understand the gap between the Syrian public and Syrian cinema—and here I mean documentaries exclusively, because they are my profession—it’s important to explain some of the axioms of this industry.

The viewer as character

Professionalism requires the existence of financial returns, like any other profession, and so one of the basics is being able to sell.

You’ll probably need to be able to sell a movie in order to make it. The terms of sale may start at the beginning of the film's creation, not after it has been made. Very few films make multiple high screening-frequency sales after they are made. These opportunities depend on many factors, not only the subject of the film itself, but also the makers of the film, the director or the producer and their experience, and the type of partnerships the film creates from its offset—partnerships with funding institutions, for example.

One of the main roles of the producer is to secure sales opportunities, i.e. the financial revenues that will enable them to continue working and investing in future film projects. Selling here generally means screening platforms, and consequently, the audience that watches them: which might start with TV but also include virtual platforms (Netflix, Amazon, iTunes, etc.), festivals that pay for single shows and even DVDs.

Quite often, the aim of working with foreign producers is to get more funding for securing a more professional team—for sound, visuals and editing—and perhaps more advanced equipment to ensure higher technical quality. However, working with foreign producers definitely comes with conditions. The first screenings will be subject to the priorities of those producers. For one, local television in the producing country will have the best chance at getting the exclusive screening. The same goes for the festivals. And the list of international festivals will come in an order based on the importance of the prizes or the specialized market of each festival.

It's important to explain these factors so that there are realistic expectations about the availability of these films. This is not only the case for Syrian documentary films, nor a result of elitist choices made by Syrian directors or producers. Rather, it is a set of industry rules that impose themselves on everyone.

One suggestion made by some directors in their work contracts is to retain the right to free, non-commercial screenings, on limited occasions. In these cases, directors have to coordinate these screenings and try to meet "their audience.” However, this proposal may in itself be an exaggerated luxury, either because of the production conditions or because work on other productions prevent them from taking the time to organise such screenings for the previous film.

Another aspect of the complexity of the relationship between the film and the audience in the Syrian case may come from the very state of total identification between audience and film. The viewer effectively becomes a character, because the war has killed more than half a million Syrians and impacted the lives of millions of others. Therefore, with every main or supporting character in every Syrian film, we expect there to be strong identification between the viewer and the characters.

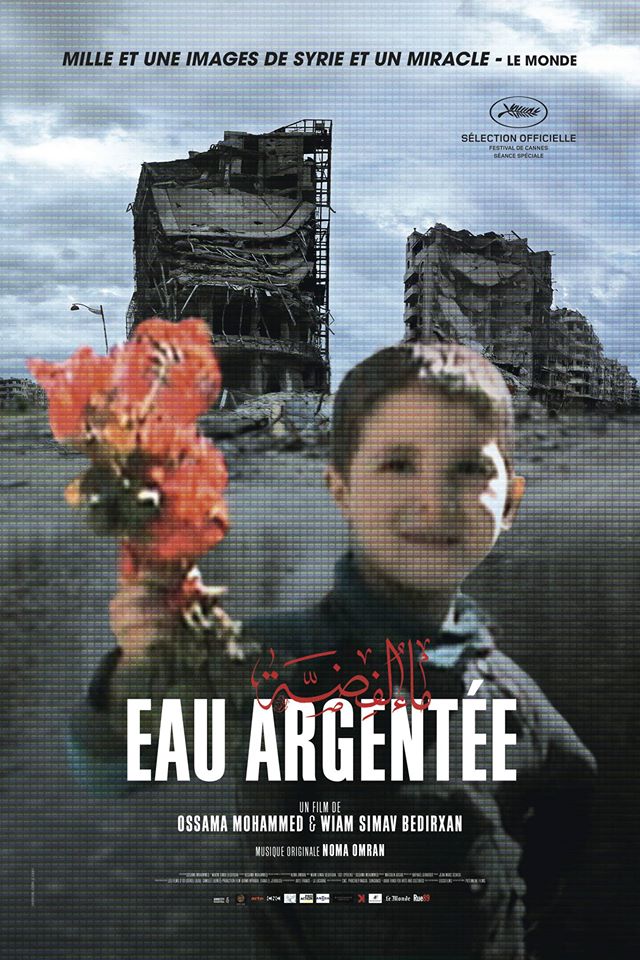

For example, in the 2014 film "Silvered Water” (Ma'a al-Fidda), viewers see thousands of Syrians: in detention centers, on the streets, checkpoints; murdered and massacred; women, men and children. Regardless, they are all Syrians! Even if we're thousands of miles away, they are us and we are them. And the events being watched are still in the here and now, because these events are still ongoing even as I write these lines.

That's why it's legitimate to question the extent of our ability to view and debate neutrally. In many instances here and there, the public expects the film to triumph, because of its cause, because it is a documentary film. I'm defeated in reality. I see a film that represents my reality. The film shows me the reality, but it doesn't triumph for me.

Here we might get into a conflict with content: The film explains an issue, and I know what happened better than it does because I am the event, the time and the place.

But can any movie tell the entire story? Every movie is part of the overall cinematic production, and the entire cinematic production is part of the bigger narrative that is Syria.

On the other hand, achieving this level of identification demonstrates the extent to which these films represent their realities, and here we may consider this to be a moment of immense success: from the previous semi-nonexistent production to where we are today. It is considered a golden era for Syrian documentary cinema, and the positive impact of the current on the future is inevitable in my opinion.

The current production density built experience for Syrian documentary professionals as well as an effective and influential international network. It will later play important roles, even in the natural selection of talent. For those whose success relies on war films, the war will end, and the talented will reap the fruits of this experience, and will be able to create creative narratives anywhere around them in different ways, and in the most "ordinary" situations.

Is today the moment for the world to see Syria?

At this point, we need to consider a number of personal films that were produced in the last three years, which will have, in my opinion, a leading role in starting the conversation about what is never discussed in our society. They open doors that were closed for decades because of the lack of freedom of speech. And yet these same films do not generate much buzz—festivals and awards ceremonies tend to focus on films with heroic protagonists, or events fixed in the contemporary. This world of heroes still tends to get priority over personal, individual stories.

On the contrary, the preferences of critics and specialists rarely match those of the audience. In festivals that announce a public preferences list (Top 10), films on this list often receive no prizes. Here, it should be noted that most directors consider the "Audience Award" as their most valued prize, without it stopping them from celebrating the awards of the jury.

With that in mind, one of the interesting questions, for me, when talking about watching Syrian cinema is this: is today the moment for the world to see Syria and to get to know Syrians, or is our turn to learn about the world never ending?

Perhaps the answer for those who love this art would be clear—both should continue in balance alongside one another.

Those that look at film as a document made to document the event, to point to the perpetrators and clarify their roles beyond any ambiguity, and to demand an explicit position of the filmmakers, primarily the producers and directors, may focus more on the importance of introducing us and our just cause to the world.

As a filmmaker, I have the luxury to combine both. We travel continents crossing thousands of miles to get to know other filmmakers and watch films that introduce us to other communities, with their pasts and presents. At the same time, we present our films. We have the opportunity to discuss them with the audience.

But putting professional considerations aside for one moment, I would definitely say that it is our right as Syrians to be seen by the world and not judged according to conflicting news briefs.

This screen can offer something far deeper than the fleeting one-minute news bulletin.