When I think about the issue of prison today, I always wonder, “How much of my awareness do I owe to prison and to prisoners’ experiences that I’ve read about?" After all, prison, as a topic and as an experience in itself, was always an eye-opener for me.

It is true that the above question is loaded with a kind of imbalance, a madness (as each writing endeavor is an act of madness, and even more so when it tackles prison in all its details). How can prison—with all the misuse of authority, destruction, frenzy, torture and self-denial that it involves—be a tool for awareness? Should it not instead be defined as a kind of vandalism, a tool for the prevention of that awareness? Don’t authoritarian powers arrest opposition figures for fear of their ideas, and the propagation of those ideas within society?

As much as this may be true, its opposite is also true. Arrests engender resistance; they expose the true nature of authority. And so they constitute a tool for awareness. Prisons established by tyrannical authorities, to arrest, kill, forcibly disappear and torture militants and opponents of their policies alike, conversely end up exposing these authorities. Their prisons, where awful practices beyond imagination take place, spark public condemnation, provoke people and raise their awareness about the authorities’ totalitarianism and insolence.

Prisons: An early interest

I became intrigued by the world of prisons early on, in my 20s, when I learned that Syria detained political prisoners. I would keep abreast of publications from rights organizations about the conditions of prisoners in Syria. I read literary novels about political detention and autobiographies of prisoners who narrated their bitter experiences in detention.

But I not only read. I also wrote about some of these works.

I wrote about Louay Hussein’s book “Loss” (Al-Fakd) and Faraj Bayrakdar’s “Betrayals of Language and Silence” (Khiyanat al-Lugha wu a-Samt). I also tackled Rosa Yassin Hassan’s “Negative,” a novel that narrates the experiences of 50 women who became political detainees.

I wrote about her novel, “Guardians of the Air” (Hurras al-Hawa) and discussed the film “Out of Coverage” (Kharij Taghtiya), which featured a political prisoner as one of its protagonists.

I also penned texts about Nelson Mandela’s autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, published after Mandela was incarcerated for more than a quarter of a century. His experience reminds us of Syrian detainee Imad Chiha, who was known as a figurehead among Syria’s prisoners, and who would later become a friend. I moved from reading and writing about the experience of detainees to befriending the detainees themselves, getting to know them closely and exploring both their experiences and writings.

My passion for the world of prisons, that nightmarish abyss, stemmed from two things. The first related to the struggle to expose tyranny by writing about prisons and supporting prisoners who society had turned its back on, and castigated, out of fear of the tyrants before the 2011 uprising, while at the same time secretly respecting them for their struggle. I wanted to demonstrate solidarity and resistance, in an attempt to liberate these prisoners from the darkness of their cells towards freedom. I sought to build an image of a new world far from the tyrannical one in which we lived. Here, exposing and criticising prisons became a quest towards a new society and state where law, human rights and freedoms could be respected, and the devolution of powers prevailed.

The second reason was more of a creative one, related to the study of prison literature and my questions about it. How can writers who experienced detention, as well as those who did not, write about that world? In the creative process, where do the boundaries of prison begin and end? Where does reality begin and end?

At that moment, I was mulling over a possible book dealing with the notion of prison in Syrian novels. Unfortunately, I have not had the time to write it yet.

Due to my growing interest in the world of prisons, I focused on that world and on human rights and the injustice of political tyranny in my first book, “Electoral Mistake” (Khataa Intikhabi). Most of the stories revolved around this topic, while others clearly tackled jails and exposed the prison wardens.

Related articles

31 October 2019

Kristyan Benedict from Amnesty International writes about the bravery and agony of Syrian activists who continue fighting for the release of all political prisoners. The Syrian authorities handed hundreds of...

At the time, I did not know that I would one day experience imprisonment first-hand. When the Syrian uprising broke out, I became active and participated in the first protest in Syria in the Souq al-Hamidiyeh in Damascus in 2011. I was detained for a whole month, which taught me a great deal about prison. To my surprise, everything I had read about prison was nothing compared to the horrid reality. In turn, this triggered yet more questions. Why couldn’t writing, no matter how honest, reflect the madness and atrocity of that place? Why does writing fall short of describing the unimaginable madness and surreal nature of that reality?

Nobody can possibly express the heinousness that would later be exposed through leaked photos from these prisons. The reality went beyond the realm of imagination, and could not be expressed by a novelist. So what was the significance of writing on this topic, then?

This situation prompted me to write about my personal experience of detention in my book, “Witnessing My Own Death” (Ka Man Yachhad Mawtah), which was later translated into Italian. I am currently writing a novel about the nightmarish world of prison and its impact on the lives of individuals and society.

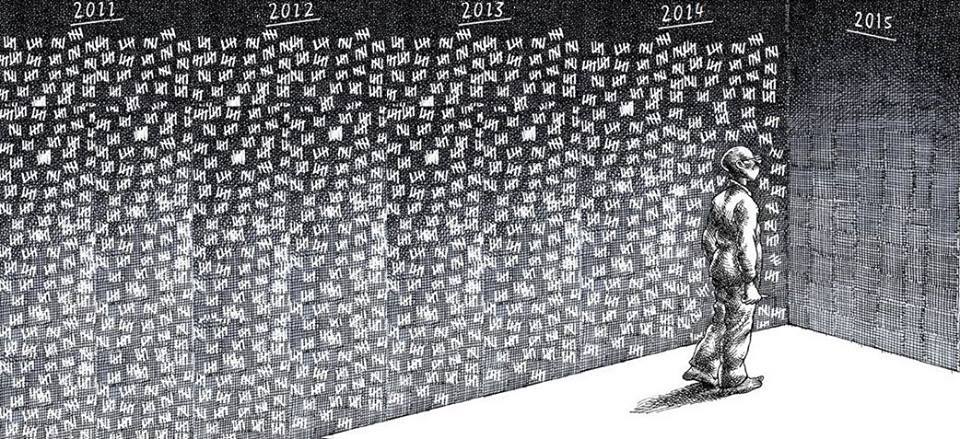

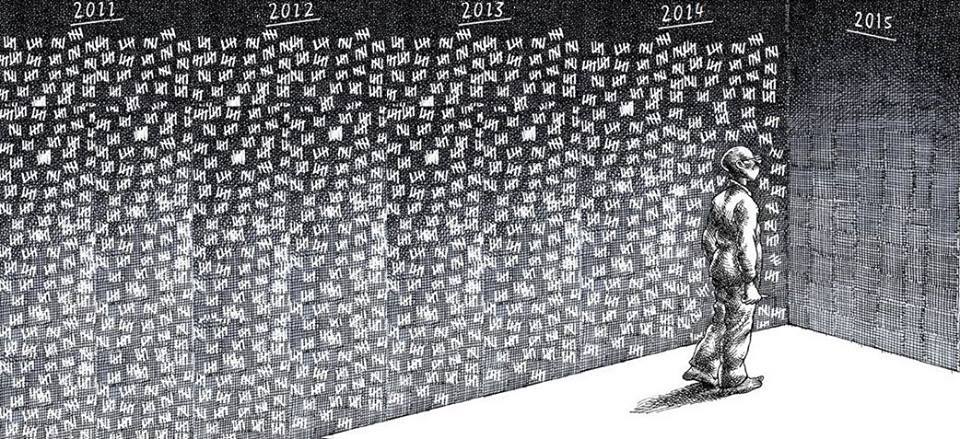

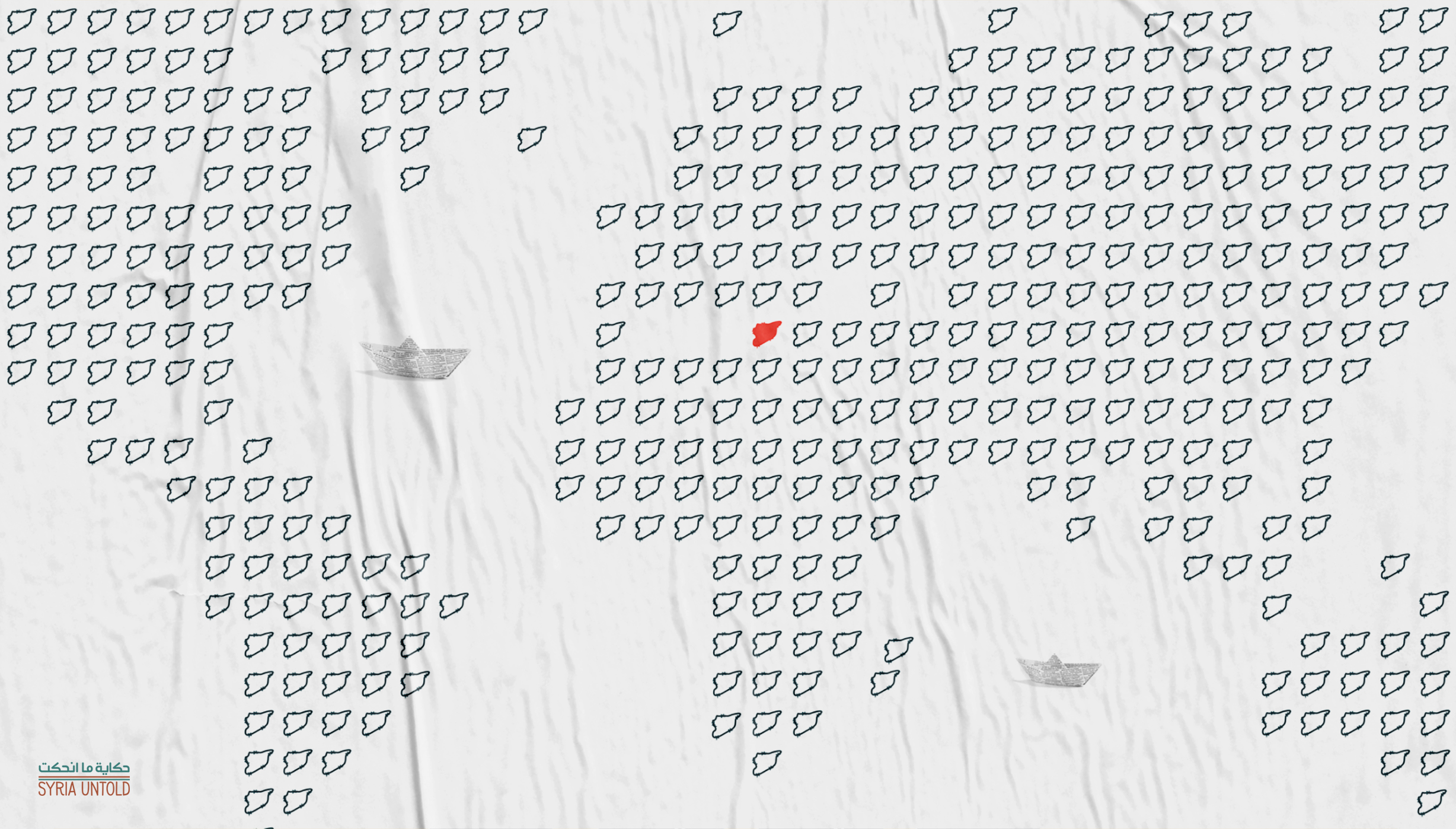

A cartoon depicting the situation of Syrian detainees since the beginning of the revolution. Image courtesy of the official Facebook page of Detainees’ Voice.

A cartoon depicting the situation of Syrian detainees since the beginning of the revolution. Image courtesy of the official Facebook page of Detainees’ Voice.In Syria's prison cells, intellectuals are born

Detention in Syria is not like detention anywhere else. It saw the birth of countless Syrian intellectuals who were culturally trained in prison, later graduating from it—whether translators and novelists, scriptwriters and actors. This experience is worthy of study and research in and of itself.

How were these people able to turn their grim, lengthy prison sentences into something akin to a school that teaches them creativity? Another under-explored topic is the various worlds within prison itself. Apart from torture and the relationship with the wardens and investigators, what were relations between inmates like? What about learning inside prison? What about books that were read, plays acted out on the unseen stages of prison cells? What about prisoners' hobbies inside? And how did they practice them?

After leaving Syria, Beirut was my first stop. I later moved to Berlin, where I am currently based.

I have been thinking, ever since, that Syria is literally one big prison. The Assad regime succeeded in secluding Syria, isolating Syrians from the rest of the world, thereby influencing the way we think. We are now capable of dealing with the world from a more knowledgeable perspective. I sometimes wonder: am I in exile, or are the people in Syria the ones in exile?

This takes us to the meaning of prison and its transformations. The significance of prison now differs from what it was in the past, and it has changed from one era to another. Nothing remains the same. So how can we define prison today?

Painting by Mwafak Kat. Image courtesy of the official Facebook page of the artist.

Painting by Mwafak Kat. Image courtesy of the official Facebook page of the artist.In his book, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, French philosopher Michel Foucault talks about these transformations and sheds light on the history of torture and prisons, discipline and punishment up until the present day.

Indeed, after I left Syria, I realised that prison was not only that world within the security branches, or behind the walls with which Assad’s regime detained people. Rather, Syria was one big prison led by a certain mechanism dominated by the culture and politics of fear, reaching far beyond banning people’s ability to move freely. For example, the regime made sure to forbid the people it did not detain from traveling outside Syria, or laying them off and preventing them from being employed elsewhere—if they even could find work in the first place. The Syrian state became a prison, and its borders were the walls of that prison. Everybody was trying to break free.

Yet another prison

In Syria, the small prison targeted the body by isolating it from others and throwing it in a cell, while the bigger prison targeted everyone. Being inside prison or outside it depended on the regime’s estimation of how dangerous a person was, and based on that, the degree of punishment they should face.

The worst punishment in Syria was not limited to restricting the freedom of the body, but went beyond that to imprisoning the mind by banning travel and books, discussions and dialogues. The small prison was the site of punishment for the body, while the bigger prison put bolts on one's mind and thoughts—the worst type of imprisonment. After all, tyranny is just another form of imprisonment.

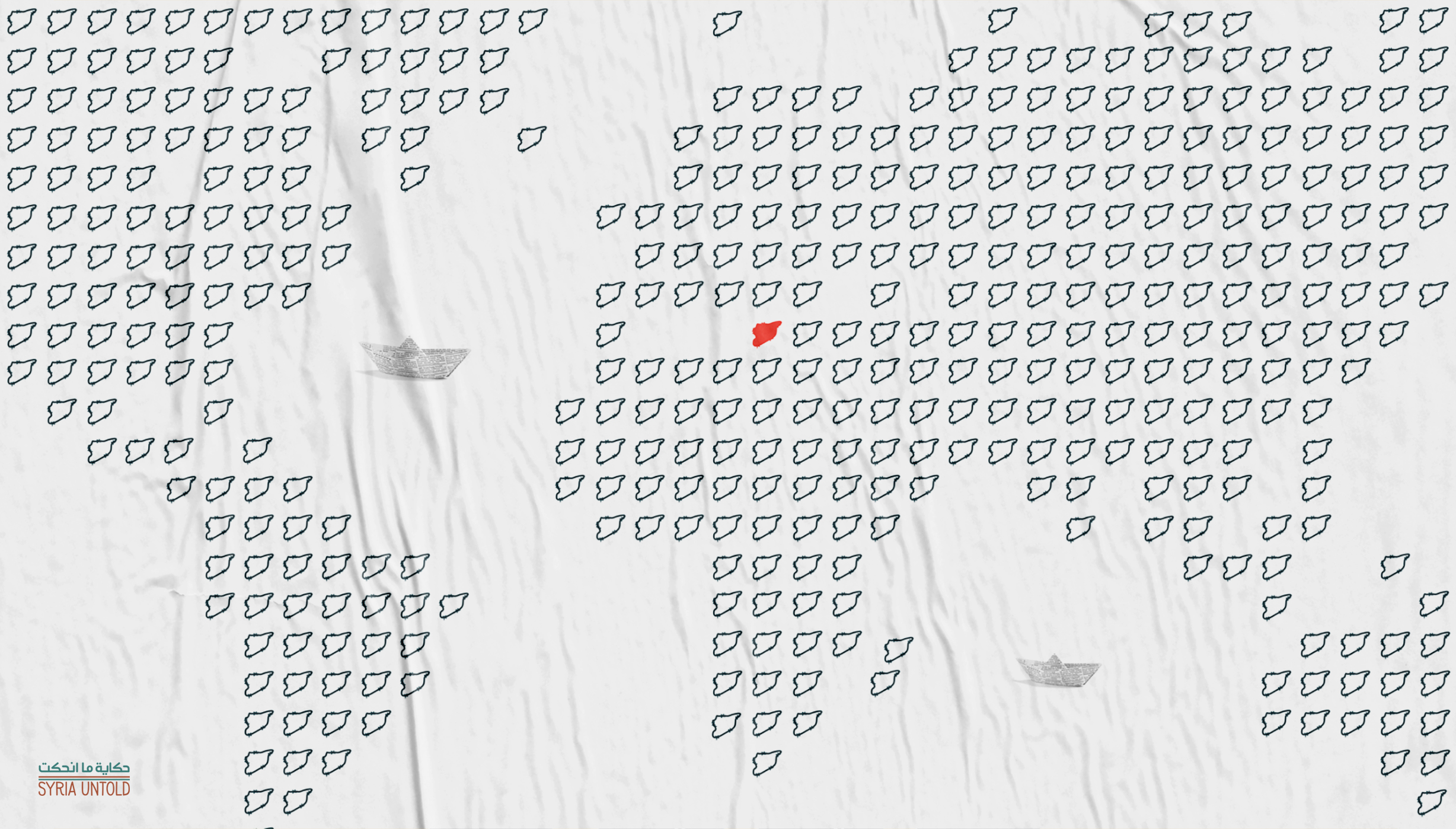

Is it just Syria that has turned into a prison, or has the whole world become one as well? Doesn’t US intelligence manage a network of hundreds of prisons across the world, under the pretext of “counter-terrorism?” Hasn’t the policy of building walls re-emerged out of fear of migration? Millions of refugees and migrants are left stranded on the borders. Isn’t that a form of imprisonment, to isolate us from one another?

'Millions of refugees and migrants are left stranded on the borders. Isn’t that a form of imprisonment to isolate us from one another?'

'Millions of refugees and migrants are left stranded on the borders. Isn’t that a form of imprisonment to isolate us from one another?'For Syrians, notably the cultured Syrians, prison has become a tool of resistance as a result of the Syrian conflict. Despite all the revelations about detention in Syria, we must never stop acting and resisting. We must continue writing about this mad world, because writing is no longer a mere luxury anymore given everything that has come to pass until now.

Instead, it has become a quest for a new narrative and life cut off from the old world, seeking the birth of a new, free world that Syrians have always dreamt of, and have revolted to achieve.

It is not out of love or nostalgia that Syrians talk and write profusely about prison in their films, books and articles. On the contrary, it is their desire to be rid of this prison forever that drives them and their quest to build a free country where detention centres exist only for rehabilitation rather than punishment.

But will that day ever come?