This article is part of SyriaUntold’s ongoing series on Syrian music. Read this piece in the original Arabic here.

“We are going through a transitional phase, shifting from entertainment music...to something more expressive. This means that the new music wave is different from the past one. We now deal with music as an art beyond song. The history of Arab music is that of song and is closely tied to the authority of discourse. However, with protest songs, we now listen to music pieces with specific themes. This has ushered in a new phase focused on voice as art... Our relationship with the word has therefore become inseparable from the musical act. Such a development will lead to a qualitative evolution in the history of Arabic music.”

-Syrian musician Adel Bou Ilaq, speaking with Daraj in 2020

In his 2016 book Art and the Syrian Revolution, Syrian writer, director and former political prisoner Ghassan al-Jebai defines art as “a mental activity and a fluid, creative social phenomenon that renews itself in content and form.”

At its core, writes al-Jebai, “art is a continuous revolutionary act. It cannot be anything else. Generation after generation, it renews itself and dismantles the deeply rooted official constant to construct a new alternative reference based on contemporary intellectual and aesthetic values and perceptions.”

Austrian writer Ernst Fischer writes, in The Necessity of Art: “To be an artist, it is necessary to own the experience, control it and transform it into memory, then turn memory into expression or material into form. Emotion for an artist is not everything; he must also know his trade and enjoy it.”

Art has a revolutionary nature because it is a revolution in and of itself. We rebel first against ourselves. It is a private and different revolution, one that speaks to the soul and digs deep into thought and notions.

The revolutionary nature of art is strongly and clearly embodied in singing because a song has, in addition to the power of words, another more influential power: that of music. Music has the power to speak to the soul and reach the conscience without a passport. It contributes to the construction of a collective consciousness and the identity of both the individual and society. Language does not limit its power, and it does not require translation.

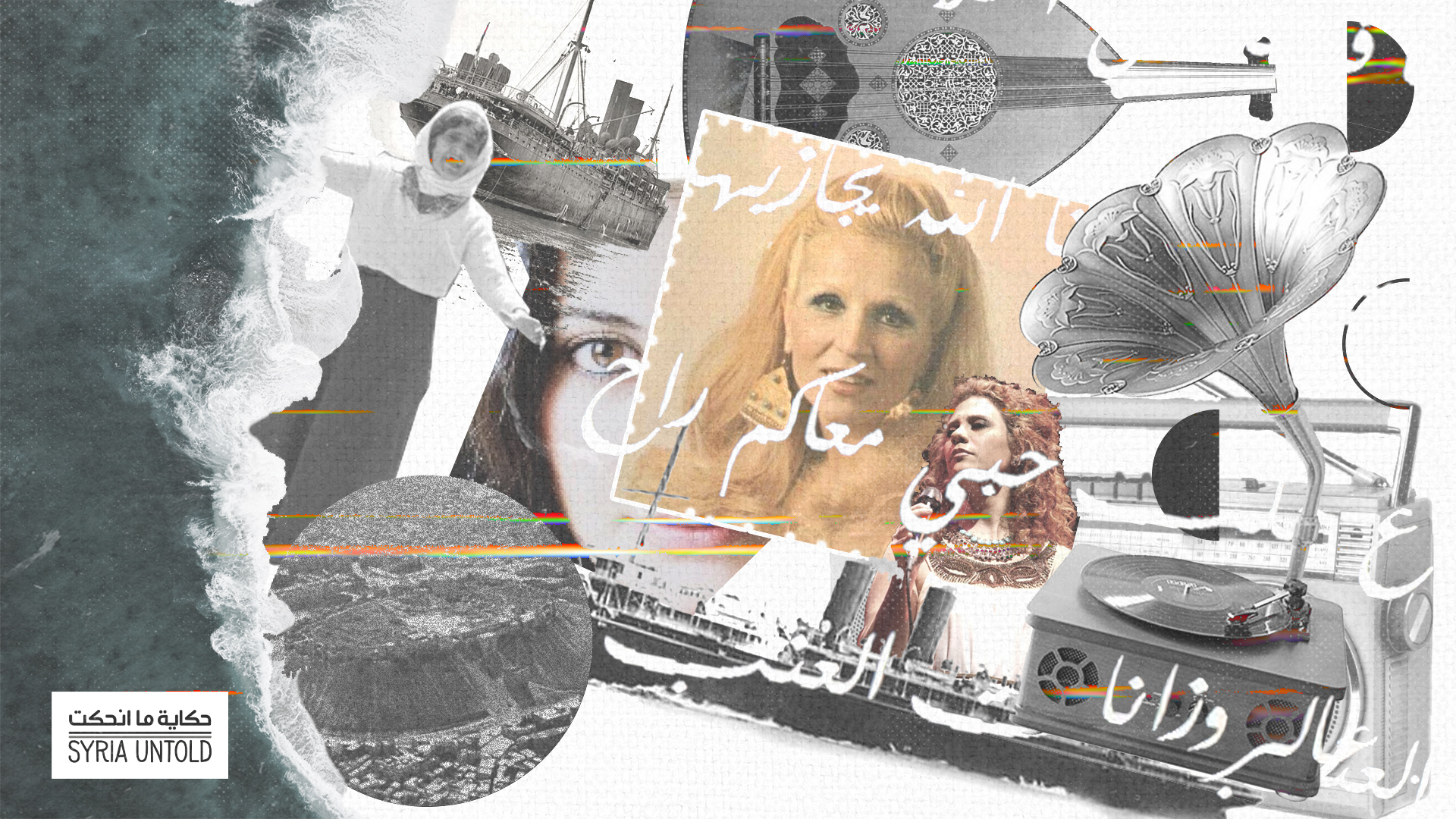

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

Protest songs have two functions. One is the action of the word, or of protest literature, while the other is the power of song, which transcends all barriers and reaches greater depths than we can imagine. By doing so, such music becomes a real reflection of our time and documents the political, social and economic situations of the people who produced it. It provides a musical narrative of the struggles of indigenous people across the world and their resistance to occupation and genocide. It depicts the truths left out of history books, which were written by the victors.

Songs depict people's stories. A story cannot be imprisoned, because the air is open and free. Song, like all art, has defeated death and oppressors. As Mahmoud Darwish put it: “We have on this earth what makes life worth living ... a tyrant's fear of songs.” They are afraid of accessible songs that unite people and that everyone can sing in unison, because those songs are empowering and exhilarating. Songs inspire familiarity and safety, even if bullets fall like rain over the heads of the singers.

A new musical genre

Over the past century, the world saw a new musical genre emerge from people’s pain, and from their resistance to all forms of political, racial and religious tyranny. The phenomenon soon spread across the world, triggering uprisings, resistance movements and demands for change and human rights.

In Italy, “Bella Ciao” became the song of the world’s underprivileged, the anthem of those fighting fascism, a ballad for freedom and resistance. In Cuba, “Guantanamera” became the song of those refusing occupation and fighting for freedom. It documented the most important period in Cuba's history. “Free Nelson Mandela” was the song written after Mandela was arrested in 1962. Bob Marley wrote “Ambush in the Night” after an assassination attempt against him in 1976. The lyrics described Jamaica's politics and the fact that the same politicians who imposed war on young men did not go off to these wars themselves.

Political music reached the Arab world with Egyptian musician Sayed Darwish’s song “Aho Dali Sar” (“This is What Happened”) in 1919. The lyrics went as such: “How can you blame me, sir, when the wealth of our land is not ours?"

Sheikh Imam came next, and he soon became iconic within this genre, documenting most phases of Egypt's modern history. To this day, our hearts beat faster as we repeat his lyrics: “Build your palaces on farms, and lock us up inside your prison cells.”

Songs depict people's stories. A story cannot be imprisoned, because the air is open and free.

The same goes for the songs of Eman al-Bahr Darwish, Mohamad Mounir, and Sami Kamal in Iraq, whose song “Souwaiheb” documented feudal rule and the rise of Marxist thought in the country. We were also united around Marcel Khalife’s songs, which set the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish to music. They touched our hearts just like Ahmad Kaabour's voice singing “Ounadikom” (“I call on you”).

Our generation cannot forget that the most influential songs that affeced us collectively were about the Palestinian cause, the Arab wound that remains open. Awad al-Nabulsi wrote the anthem “Ya Leil, Khalli El Assir Ta Ykamil Nwahou” (“Oh Night, Let the Prisoner's Wails Continue”) in 1929, using a sharp object on the walls of his prison cell. The next evening, the British occupation forces, colluding with Zionists, executed him for his opposition to the influx of Jewish settlers in Palestine. It is our anthem. The songs of the Palestinian band Alaashkeen, such as “Walla La Zraak Bl Dar Ya Oud Lawz al-Akhdar” (“By God, I Will Plant an Almond in My Salon”), and those of Al Ard Palestine move us and reopen our wounds. And the voice of the late Reem al-Banna carried the Palestinian soul as she sang “Ya Leil Ma Atwalak” (“Oh Night, How Long You Are”).

Protest songs in Syria: Samih Choucair as an icon

The closer we move to the Syrian experience with songs of resistance, the more we remember the experiences of Syrian musicians Bachar Zarkan and Fahed Yakn, and Ziad Harb's satirical song “Kil Ma Ilna La Wara” (“Moving Backward”), which depicts Syria’s tragic situation.

Yet the most important examples of Syrian resistance songs are those of Syrian musician Samih Choucair. They serve as a sort of panorama, documenting the history of the region for the past 40 years. In his first song, “Li Man Oughani” (“For Whom Shall I Sing”), Choucair sang for “the poor, the ashes of this world's fires.” He also sang about suppression of freedom of speech and the pain of an occupied Palestine. Choucair dared himself, his voice and our spirits to choose the steep road and fight all forms of oppression, waste and platitude. He gave us art that spoke of the depth of our experiences when we fight oppression and then return to ourselves, exhausted yet safe.

The more this musical experience evolved, the closer it got to us. In 1984, Choucair released “Bi Yadi al-Kithara” (“A Guitar in my Hand”), then “Hanajirokom” (“Your Voices”) a year later. Samih's artistic identity started becoming clearer when he produced “Zahr al-Roumman” (“Pomegranate Blossoms”) in 1990. This work was widely shared by individuals, rather than through the media, which actively fought it.

“Ya haif,” or “alas!” is an expression that every Palestinian, Syrian, Jordanian or inhabitant of the Levant understands. It expresses the deep grief intertwined with bitterness and dignity.

During this time, Choucair performed more than 20 Palestinian songs. He documented the Sabra and Shatila massacre, the 1982 siege of Beirut and the deportation of Palestinians in the song “Roummana” (“Grenade”). He sang in support of Palestinian prisoners in his song “Asfour” (“Bird”) and for prisoners of conscience across the Arab world in “Ghorfa Saghira wa Hanouna” (“In a Small, Gentle Room”). Choucair also sang Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry in eight songs, including “Beirut” and “Minkoum al-Seif” (“A Sword from You”). In his song “Heen Naatadou al-Raheel” (“When Leaving Becomes a Habit”), he addressed the Palestinian diaspora and brain drain from Syria. The song “Fi Hana Saghira” (“In a Small Bar”) depicted the deaths of decent Syrians trying to make a living under a regime openly robbing them. He sang for the Kurdish right to equality and justice in “Ghanni Ya Shayfan Ghanni” (“Sing O Shayfan Sing”) and for the occupied Golan Heights in “Ya Golan Wa Yalli Ma Thoun Aleyna” (“O Golan, Our Hearts Go Out to You”). For 20 years, every Syrian independence day he stood in Ain al-Tineh, on the Syrian side of the border fence cutting off the occupied Golan Heights, singing the resistance song “Zahr al-Roumman” (“Pomegranate Blossom”). Samih also sang “Mouzaharat” (“Protests”), in which he heralded the Palestinian Intifada and the Arab Spring before they happened.

Song and the Arab Spring

Because this generation has lived through historical turns of events, we are both lucky and unlucky at the same time. The outburst of the Arab Spring revolutions and the songs that accompanied them carried the torch from Tunisia to Tahrir Square in Cairo and the squares in Sanaa. Then, we heard the voice of the first Syrian shouting “Long Live Syria, Let Bashar Fall.”

We cannot forget how the songs of the Syrian revolution affected us—how they not only contributed to the events in Syria, but also to inspiring protesters and easing the heaviness their of detention, murder and torture. Abdul Baset al-Sarout’s song “Janna, Janna Ya Watana” (“Heaven, Heaven, Our Country is Heaven”) and “Yalla Erhal Ya Bashar lil Kashoush” (“Leave, Bashar”) documented our revolution and its initially noble goals.

Ziad Harb, for his part, sang “Darayya” to document a peaceful protest. His song “al-Suwayda” marked the return of peaceful protests in Suwayda governorate in 2020, after nine years of war. Everything died in us during those intervening years.

As these songs remain in our memory, we will always remember the first one about the revolution, 10 days after the first four martyrs fell in the Daraa protests on March 18, 2011. The song was Samih Choucair’s “Ya Haif.” In it, he documented the Syrian regime’s arrest of 15 children in Daraa, and its usage of live ammunition against the protesters condemning this move. He documented the nature of Assad's regime, which knelt before Israel for over 40 years, yet did not hesitate to open fire on its own people.

“Ya haif,” or “alas!” is an expression that every Palestinian, Syrian, Jordanian or inhabitant of the Levant understands. It expresses the deep grief intertwined with bitterness and dignity. It reflects the degrading treatment of dignified and free people by oppressors. “Ya Haif” quickly became a symbol of the revolution. The Syrian regime could not muffle it or hide the facts depicted in the song. It was the voice of the massacred Syrians. After it, the song “Sourakhon” (“Oh Women!”) continued the story. In our moments of optimism before the world failed us, the song “Arrabna Ya Houriyi” (“Close to Freedom”) resonated. When the world let us down and all regional powers abandoned us, Choucair described the emigration of Syrians and their bitter deaths in the Mediterranean in the song “Qader Ya Bahr” (“Powerful Sea”). After flags and stories that do not resemble us started claiming the Syrian opposition, we watched our dreams vanish right in front of our eyes. Choucair’s song “Ya Ibn El Balad, Khali Aynak Aal Balad” (“Men of This Country, Keep an Eye on This Country”) was a warning. To express the revolution as an undying idea, he sang “Ayazounou” (“What Does He Think?”).

Choucair wanted to compare the Syrian revolution to a phoenix which rises from its ashes. Just like the phoenix, the idea of the revolution returns and calls for freedom, justice, a civil state, equality and a democracy ruled by laws that uphold everyone's rights.

On the 10th anniversary of our most beautiful and painful memories, may any experience that built us and raised our self-awareness remain alive. May the idea and the revolution itself live on. May our music reach all corners of the world and blossom with beauty, resistance and a voice that cannot be silenced. We will continue to sing along with Choucair:

When my voice disappears, yours will stay

My eyes are on the future and on you

The song outlives the singer

And lives on

Uniting and mending broken hearts.