This article is part of SyriaUntold’s ongoing series on the world’s “Little Syrias,” communities of Syrians in the diaspora.

Mohammad and Amin snuck onboard the merchant ship docked at the Beirut seaport. It was 1913. They had just become stowaways, Mohammad at 17 years old and Amin at just 14. The boys wouldn’t be discovered until after the vessel had already reached the high seas.

According to the story, passed down through generations of my family, the boys’ young ages spared them from being tossed overboard after they were discovered and confessed to their “crime.” The trip, however, would not be free of charge. The two young Syrian stowaways assisted the crew with daily tasks, and as the days went by, the ship drew closer to its final destination: Buenos Aires, Argentina. There, Mohammad and Amin would make a new home more than 12,000 kilometres from where they had set out.

Argentina was a popular destination for European and Arab emigrants by the end of the 19th century and until World War I. The Argentine government wished to colonize the Pampas plains with northern Europeans and pushed forward with policies to encourage immigration. According to Argentina’s National Census, there was a net immigration of 3,300,000 people from 1857 to 1895, helping to increase the population of the country from 3,955,110 to 7,885,237. By 1914, one year after Mohammad and Amin landed in Buenos Aires, one in three people living in Argentina were born abroad, according to historian Alberto Sarramone.

Arabs, however, represented only a small share of these newcomers. Italian and Spanish immigrants alone (not the northern Europeans that the Argentine government had hoped for) constituted about 82 percent of those arriving in Argentina during this period. Some Arab immigrants, like Mohammad and Amin, left no traces at all at the immigration office. Still, whatever category (or no category at all) they were registered under, by the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Lebanese, Palestinian and Syrian immigrants amounted to about 65,000 people, or 1.6 percent of the Argentine population, according to historian Ignacio Klich.

I think Mohammad chose Amado because of the similarity in meaning to his own name, that of the Prophet Mohammad. Nobody knows for sure, though.

My great-grandfather Mohammad was born and raised in the town of Muadhamiyat al-Qalamoun, some 60 kilometers north of Damascus. Though only 17 years old when he was a ship stowaway on the eve of WWI, and like many Syrian citizens in more recent years, he chose to leave his home to avoid war and a seemingly probable death. More specifically, he was on the run from safar barlik, or the Ottoman Empire’s forced military conscription; it didn’t particularly matter that he was so young.

Mohammad and his younger brother Amin’s lives in Argentina would hardly be easy. Historian Abdelwahed Akmir notes public discrimination and obstacles to integration, while according to Klich, there were policies in place to specifically curb Arab migration to Argentina. Anti-Arab racism was so widely accepted that Argentine government officials publicly aired their opinions against Arab immigration. Records of their statements remain at the National Directorate for Migration in Buenos Aires.

‘Little Syrias’ in a big world

26 July 2021

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

The prejudice against Arabic speakers and Muslims was not limited to the capital city. In a letter dated June 7, 1965, Domingo (nicknamed Titino), one of Mohammad’s sons, shared a sense of guilt for not being able to understand and communicate in Arabic with his father’s family in Syria. Argentines often laughed when they heard spoken Arabic, Titino wrote. For that reason, Mohammad and his wife, Schafika (later named Sofía), banned the use of Arabic language in their household. “A somewhat stupid excuse, but the only one,” lamented Titino. Mohammad changed his own name to the Latinized Amado, meaning something like “beloved” (assumedly by God). I think Mohammad chose Amado because of the similarity in meaning to his own name, that of the Prophet Mohammad. Nobody knows for sure, though.

Sometime after arriving in Argentina, Amado found residence in San Vincente, a small and predominantly Italian Catholic agrarian colony in the province of Santa Fe. How he got there remains a mystery to my family.

In San Vincente, most residents were originally from Northern Italy and spoke Piedmontese—an Italian dialect widespread at the southern foot of the Alps. In fact, Mohammad’s oldest children, Isolina, Oscar, Roberto and Yamil, grew up speaking Piedmontese rather than Arabic. After all, Piedmontese was the prevailing local language in San Vincente and a tool to engage in commerce.

He seemed, in his own way, to be honoring the old saying: “When in Rome.”

Although Mohammad’s arrival to San Vincente is full of blanks, threads of his life there were recorded orally and passed on to us younger generations. Through these stories we can trace his and Amin’s initial steps back to a time when they were small merchants, when they wandered between the low-lying houses in the peripheral farmlands of San Vincente. Instead of carrying a suitcase with small household goods like other peddlers in big cities, Mohammad and Amin simply pushed a wheelbarrow. During this time, and while on a trip to Santa Fe city to buy stock, Mohammad met Schafika. As the story goes, she was an orphan who had been handed over to a wealthy Lebanese family for care. That family, the Chemes family, migrated first to Brazil and then Argentina. Somewhere along the way, Schafika became Sofía.

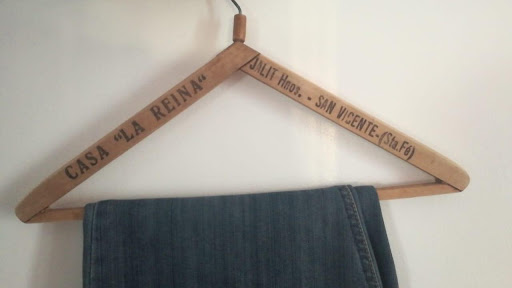

People in San Vincente knew that Amado never made a big fortune selling his wares. He did, however, save enough money to open a supermarket called Casa La Reina (The House of the Queen) right next to his house, on the corner of the Galvez and Manuel Belgrano streets and a block away from the town’s main plaza. And though much of Amado’s commercial success came from personal sacrifice, we often forget that he also sidelined Arabic and Islam to integrate socially.

Amado passed away on July 25, 1970. Sofía turned ninety-five years old before she died on September 22, 1995. They raised six children: Isolina, Oscar, Roberto, Yamil, Domingo and Mohamed. Isolina finished elementary school and made sure her brothers received a formal education. Oscar, Roberto and Yamil followed Isolina’s steps and attended Elementary School No. 401 Juan Bautista Alberdi in San Vincente. As for Domingo and Mohamed, both became medical doctors and found some success in public office. Mohamed participated in the 1987-1989 reorganization of the Pharmaceutical Industrial Laboratory, an institution created in 1947 to produce and supply medication to hospital pharmacies. Domingo was a candidate for the Municipality of Santa Fe in 2003.

Unfortunately, Mohammad did not live to see all those successes. Still, I like to imagine his pride at seeing Domingo and Mohamed graduate from medical school—him, a man who (according to my family’s stories) left Syria as a teenage stowaway with nothing but a few British pounds as World War I loomed on the horizon.

Oscar, Roberto and Yamil were the family entrepreneurs. While living and selling oil out of a tank-truck at the industrial suburb of Lanus, Oscar visited Roberto and told him to move back to San Vincente to start a harvest business. According to Roberto’s wife, and my grandmother, Elvira: “Oscar told Roberto to return to San Vincente and buy two harvest machines with state sponsored loans.” He did so, and found great success in their joint venture.

Some local elders still reminisce, with tears in their eyes, about those times each year when people lined up in the streets of town to wave goodbye to Oscar and Roberto’s 12 harvest machines and over 40 employees. “It was like watching an exodus. The town would be empty after their departure,” said Ricardo, a seasoned bartender who at the time was a young boy. Eventually, Oscar and Roberto parted ways to lead new projects and leave the harvest company to their sons.

Mohammad also taught his children about the value of family. “If the grapevine could speak,” Faisal, one of Oscar’s sons, told me recently, “it would probably tell us about all of our New Year’s and Christmas celebrations.” Yes, Amado’s integration included the celebration of all the Christian holidays. He seemed, in his own way, to be honoring the old saying: “When in Rome.”

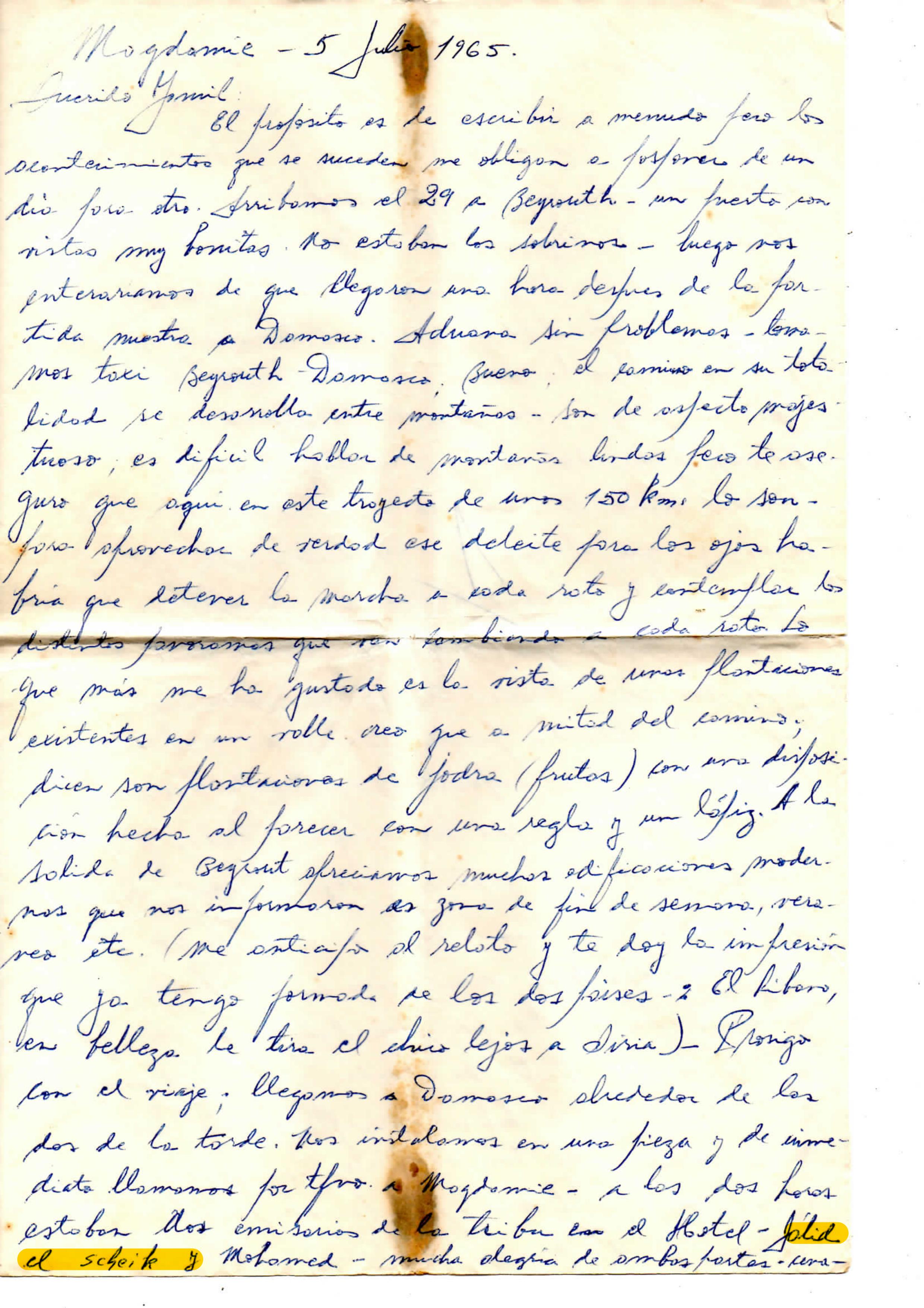

Even as he became Amado, Mohammad never fully forgot about Muadhamiyat al-Qalamoun, Arabic or Islam. Some 52 years after he first left as a teenager, Mohammad finally returned home to Syria for a visit. My family’s only window into that emotional journey is a series of letters from Titino. He was the only child of Mohammad and Schafika to accompany them to Lebanon and Syria.

The correspondence is dated between June and August of 1965 and addressed to Roberto and Yamil. In it, Titino records with a great deal of detail their arrival at the port of Beirut, the car ride from Beirut to Damascus, and Mohammad’s eventual arrival in Muadhamiyat al-Qalamoun. Most important are the family reunions and the emotions Titino saw and felt.

Titino traveled to Muadhamiyat al-Qalamoun one day before Mohammad, and wrote down his first impression: “At the news of dad’s presence in Damascus the whole town began to descend upon [the capital city].” After seeing his long-lost brother Mustafa amid the crowd, Mohammad remarked: “I could have recognized him in the middle of a mob because of the traces left by smallpox in his body.” Minutes later they were all on the road to Muadhamiyat al-Qalamoun under the guidance of Khaled, who had been the town mayor until 1951.

When they arrived, Mohammad met his only living sister, Mariam. His other sister, Fatme, had died the year before. Still, it was a moment of joy, wrote Titino. “Dad gave Mariam a hug and broke into tears, and everyone around began to hug and kiss us.” Titino then warned his brothers: “Upon my return, I will need a few hours to fully describe this moment.” Soon enough, the whole town paraded in front of Mohammad to greet him.

At some point or another Mohammad began to wander through town to find his childhood home. There it was, on the other side of the main road, in the old quarter, albeit only the stone foundation. Only his memories remained of the rest of the house. Did he feel sadness for having returned home too late? Happiness for having returned at all? Only Mohammad knows.

My curiosity about Mohammad’s life didn’t come from thin air. It is a curiosity that constantly reminds me of the bits and pieces that make up the history and identity of Arabs in Argentina. It is a never-ending reconstruction of a story that begins anew with every Arab-Argentine at some point or another in their life. It is a constant search for the self that initiates with the first bite of kebbe and plate of yabrak—at least that is how it starts for me.

And maybe, for me, it is a search that will end when the body reunites with those who remain living in Muadhamiyat al-Qalamoun. Or perhaps it will never end at all.

Editing by Madeline Edwards