SyriaUntold’s illustrator and multimedia editor Rami Khoury revisited editor-in-chief Muhammad Dibo’s essay from July about prejudice, placelessness and alienation in Germany.

Rami’s picture story is below, with snippets from Muhammad’s original written piece.

When I first arrived in Berlin, a Syrian who had been in exile for a long time told me: “I live downtown, in the middle of Berlin.”

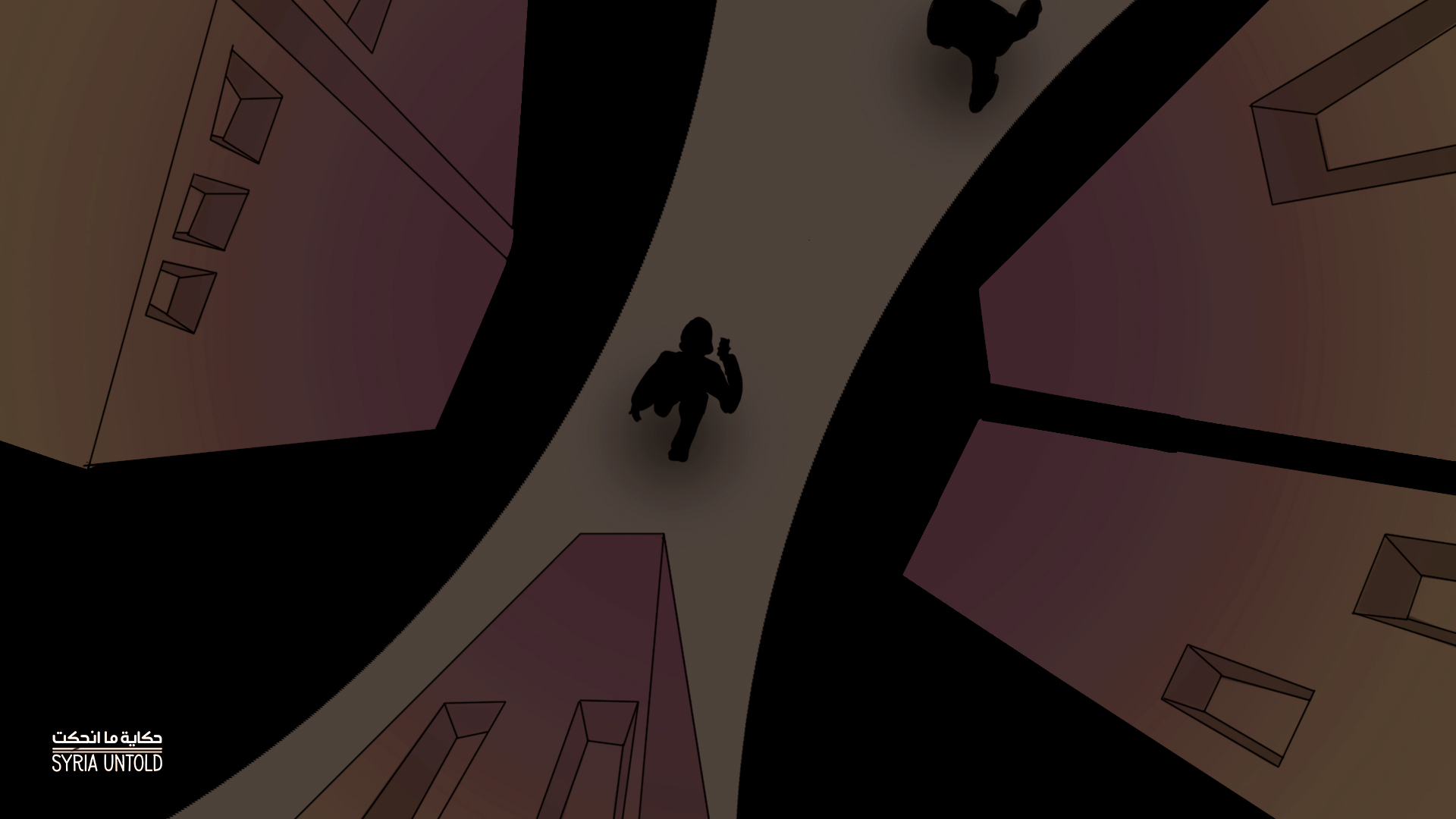

After a while, I’d come to pay attention to these little phrases, repeated on the tongues of many Syrians. Most of them don’t live downtown in the sense that they mean. This discrepancy made me aware early on of these phrases, released by people’s consciousness though subconsciously reflecting other repressed, hidden meanings.

I think something along these lines happens everywhere in the world. My partner and I live in the Charlottenburg area of Berlin. We were surprised at how people often reacted to this information, opening their mouths: “Oh, you live there?” In the minds of many Germans, Charlottenburg is a rich, affluent area, though in reality most residents are longtime tenants, paying cheap fixed rents. With time, part of the neighborhood has indeed become home to the rich, with a few middle and low income residents as well. Still, this reality hasn’t changed the neighborhood’s reputation as a wealthy one.

I think when those of us in exile say the phrase “I live in the middle of Berlin,” we're searching for someplace, something to compensate for what we have lost. We are trying to prove ourselves to others, or perhaps to make up for a deficiency we feel inside ourselves, one that can be seen not in this phrase alone, but in many other phrases and contexts as well. And yet we continue saying it with confidence, without realizing the deeper meanings hinting at our internal struggles, our alienation, our lack of stability in any one fixed location.

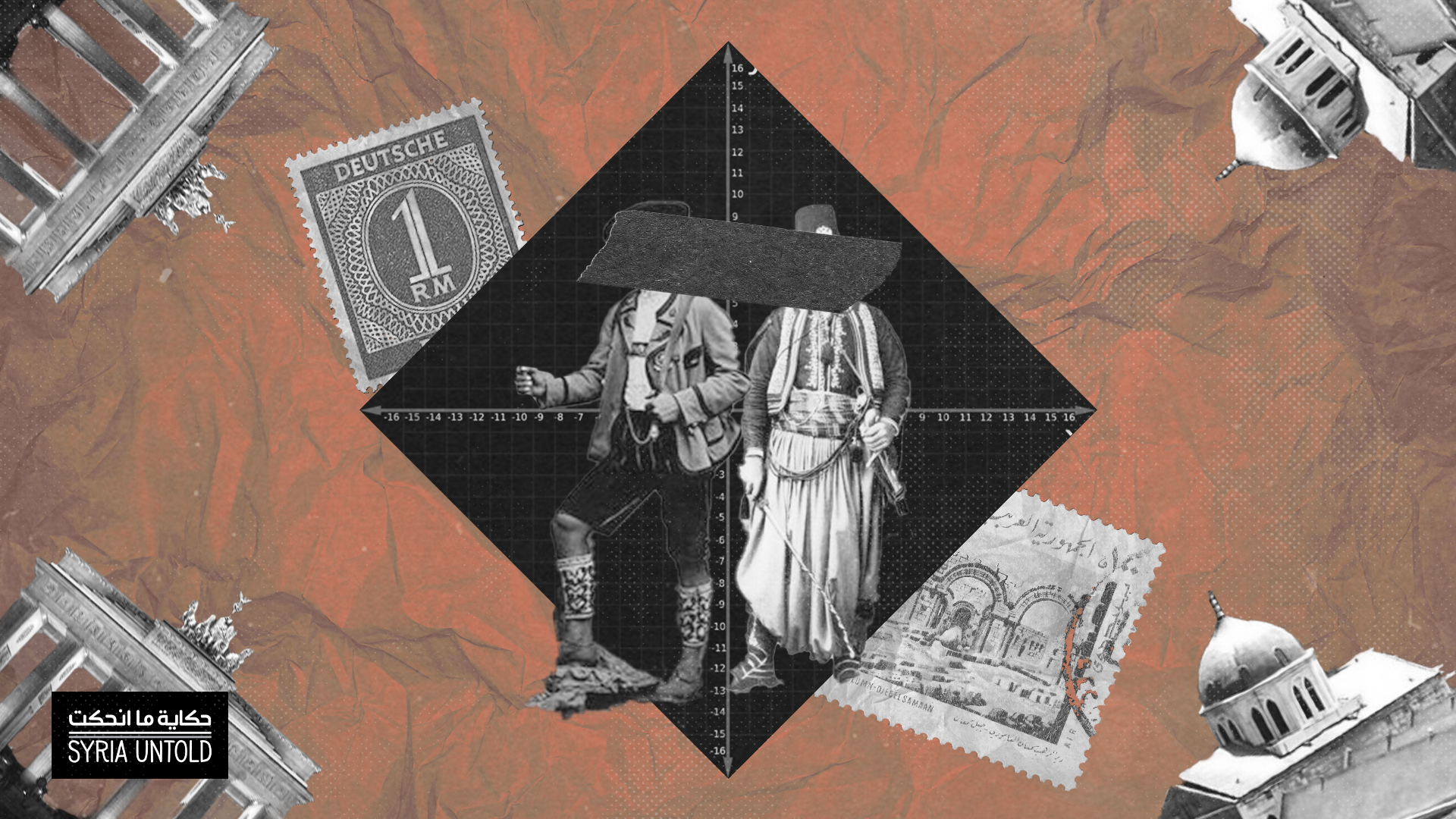

When two of us meet again after a long time apart, one of us always says to the other: “How long has it been? God, we became Germans without even noticing” (this is something the author of this article has said himself). There is an idea fixed in the subconscious minds of Syrians and exiles that Germans only make appointments with friends after three or four months apart. Perhaps this phrase also holds some other reference to Germany’s difficult bureaucracy.

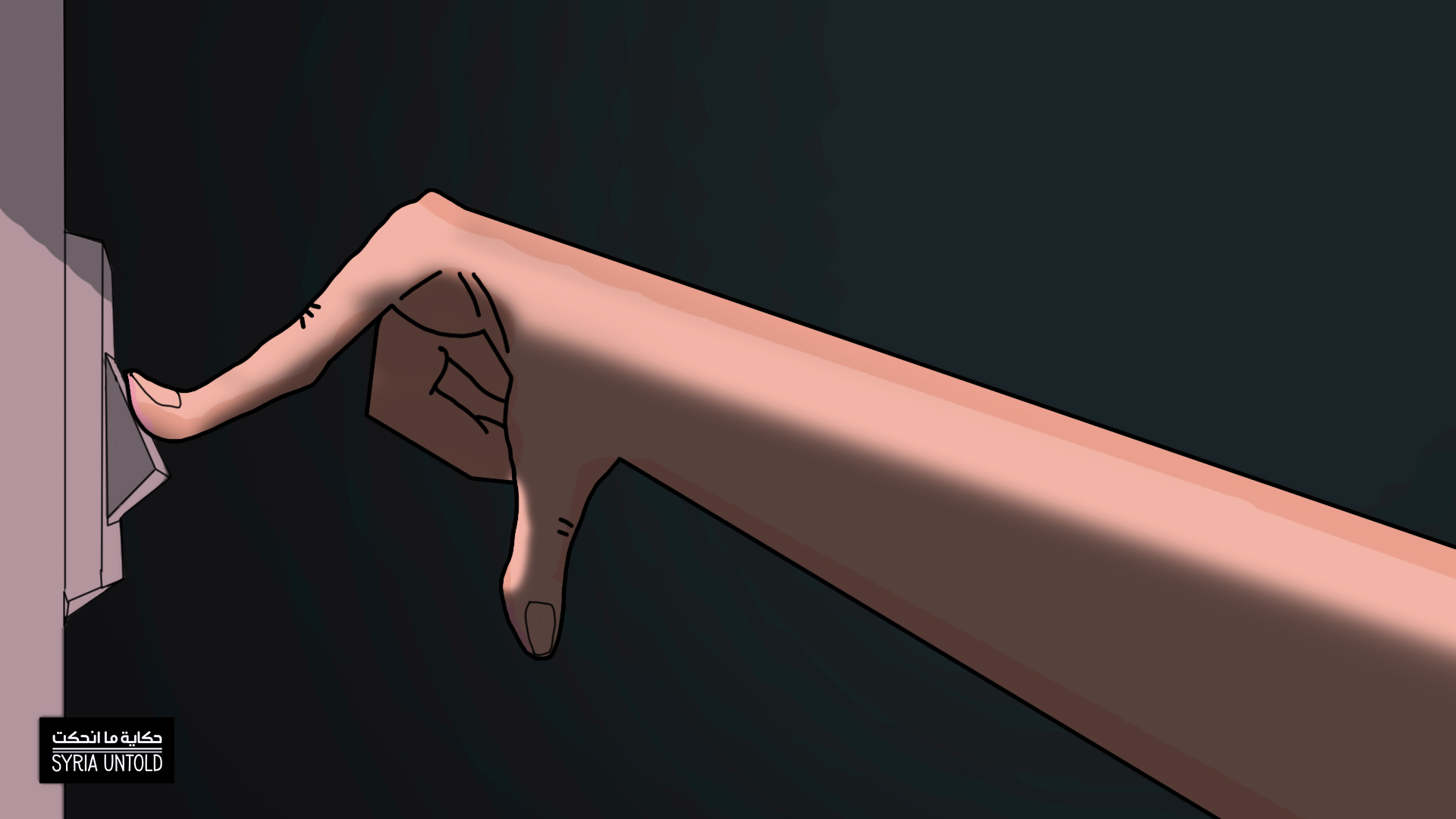

But saying to someone that “we’ve become Germans” doesn’t mean here any sort of real integration. Rather, it’s a way to mock the situation we’re in, one that doesn’t allow friends to meet naturally without previously drawn-up plans. This is quite unlike what we used to do in Syria, where it was enough for a friend to ring your doorbell with no prior warning (it would be rude to turn down their request to enter). And if you wanted to be a bit more polite, perhaps you could call beforehand to tell your friend, “I’m on the way!” or “Meet me at the cafe in half an hour.”

This type of intimacy and comfort with which we used to meet friends has been lost by Syrians in exile, replaced with a pathological nostalgia. Now we don't know what we really want.

Read Muhammad Dibo’s full essay on alienation and exile in Germany here.