SyriaUntold originally published this story in Arabic here.

Climb aboard the bus of his body

or wait for him at the next station

he is now accused of a murder

accused of destroying the bloodstream:

the first kiss is a bullet,

And the last bullet love.

Many Syrians are familiar with the politically-tinged love poem “Destruction of the Bloodstream” by Riyad Saleh Hussein. Few of them know, however, that this poem was published for the first time in the mid-1970s, in a tiny underground literary zine that never bore a name. Its founders, a group of leftist writers and political activists, agreed on calling it, simply, “al-korrasa,” Arabic for “the pamphlet.”

Wael Sawah: 'I sacrificed literature for politics'

26 May 2021

Damascus’ forgotten ‘Saturday of blood’

07 September 2021

“Giving it a name would have restricted it to a certain identity, and we didn’t want anything to restrict our freedom,” Wael Sawah, one of the pamphlet’s founders, and a longtime writer and activist, tells SyriaUntold.

“We thought that giving the pamphlet a name would have led the authorities to ask about its licensing and affiliation, but in any case, this didn't stop the mukhabarat,” says Syrian poet Faraj Bayrakdar, who joined the pamphlet's editorial team and was later arrested along with the poets Riadh Saleh Hussein and Khaled Darwish because of it.

But why was the Syrian mukhabarat afraid of a small, sometimes handwritten, cultural and literary pamphlet that was privately printed and distributed?

Turbulent 1970s

The 1970s were a stormy decade for Syria, Sawah remembers. “In 1976, on the Palestinian Land Day, there was a demonstration planned. It started from Damascus University, and mukhabarat agents who were waiting just outside went after everyone. Some demonstrators were arrested and others beaten in what turned Land Day from a Palestinian event into a Syrian one. In turn, this Syrian event led to the rising tide of leftist revolutionary action in Syria. That same year, the League of Communist Action emerged.”

Syrian poet Faraj Bayrakdar, who was involved in the LCA’s later incarnation, the Labor Communist Party, recalls: “Under Hafez al-Assad, the political dictatorship became comprehensive. It included the political, economic, social, cultural and media aspects, among others. Under a dictatorship of this kind, even demonstrations to glorify Assad or his regime were forbidden without a permit from the intelligence services.”

This reality brought about a revolutionary and leftist tide in the 1970s, one that resonated among many groups of young Syrians in line with the general Arab and regional climate, with roots probably dating back to the previous decade. “After the defeat of 1967, a general wave of radicalization emerged in the Middle East and North Africa within the Arab nationalist and leftist parties,” according to researcher Joseph Daher.

Syria witnessed parts of that radicalization process, Daher adds. “Marxist circles” arose in the mid-1960s, in the form of discussion groups spread out across the country. Participants discussed the political issues of the day through a Marxist lens. Most of the core members of these groups were students and former Arab nationalists hoping to challenge tyranny and find a way forward in Syria post-1967.

Syria’s Labor Communist Party, a rich political history

16 October 2020

Husseiba Abdelrahman: I ask myself why I decided to stay in Syria

26 October 2021

Writer and dissident Sawah, poet Bayrakdar, storyteller Jamil Hatmal, poet and journalist Bashir al-Bakr, writer Fadia al-Ladkani, and poets Hassan Ezzat and Khaled Darwish all took part in this stormy political climate.

Ezzat, one of the pamphlet’s founders, remembers those years: “We were a group of friends with a stance that needed to be crystallized. We did not have a party. On a personal level, I didn't want to join any party. We were defying the existing parties and the authorities that had created a closed atmosphere. We didn't want to be like them.”

“I asked many questions but never got a single answer,” Ezzat continues. “I kept searching until I heard about Marxism; this was after Nasserism had already spread. Through the Egyptian books that were flowing into Syria, I laid eyes on Marxism, which contradicted the path I was treading along. I began reading about it with a critical eye, and then I could no longer go back. I had studied in the countryside and seen the extreme poverty before I reached the city, and this offered me a view that differed from what the regime published in the newspaper and the media. In short, we were a generation that wanted to change the world, but how?”

For them, changing the world was not going to happen through politics, but instead by breaking the barriers of the dominant culture at the time “through a new form of poetry with new visions anticipating the future,” as Ezzat says.

“The cultural climate was restricted for us at the time,” remembers Sawah. “The idea of the pamphlet came from the fact that young people of our generation did not have a platform to publish whatever they wanted. I would publish articles but not any articles I wanted. The cultural climate in Syria in the 1960s was dominated by the Baathist Left through names such as Mohammad Omran (Al-Thawra newspaper), Ali Kanaan (the culture section of the Tishreen newspaper), Ali al-Jundi and Adel Mahmoud (culture, Al-Baath newspaper) and Mamdouh Adwan (culture, Al-Thawra), some of whom were Baathists at the time. Others had left the Baath movement along with some left-wing intellectuals.”

Bayrakdar concurs. “We were activists publishing articles in official newspapers, but it was simultaneously clear to us that these media outlets were restricted in terms of creativity. Therefore, we were looking to break all restrictions and all kinds of censorship. I decided to no longer publish in any official media outlet,” Bayrakdar says.

Beginnings

Within this cultural climate, in the mid-1970s, Hassan Ezzat's poem “The Alexandrian Gazelle and the Snake Charmers” won a literary competition at Damascus University. Wael Sawah’s short story “Why Did Youssef al-Najjar Die?” won the same award. The two men became acquaintances, after which Ezzat introduced Sawah to Jamil Hatmal, who was working on a short story.

This is how the so-called “Three Musketeers” met, later to form the pamphlet's first editorial board. Others would join them in the venture, including Fadia Ladkani, a friend of Sawah.

“Sawah was the one who opened the Damascus cultural circles for me,” Ladkani tells SyriaUntold. “I got to know a Damascus that was different from the one in which I grew up before meeting him, a Damascus full of well-known writers, artists and poets.”

Ezzat and Sawah won the same literary prize that following year, but Ezzat was unable to publish his work in official Syrian outlets due to “the nature” of his writing, he says. “This prompted us to search for publication outlets, especially after a prize-winning poem of mine was not published."

“This is where the idea for the pamphlet came from,” Ezzat continues. “We began to think and look for a place that resembled us, that constituted a free and unsuspecting atmosphere. We wanted a place capable of conveying our voice to the people,” or, in the words of Bayrakdar, “a place capable of conveying the voice of young Syrian writers who were fed up with the reality, the inaction and the submissiveness.”

“I cannot say in the literal sense of the word that I was one of the founders,” Ladkani admits. “At the same time, yes, I was one of them, and I attended the first founding session. My role, truth be told, was both secondary and major! I remember arriving with Sawah one day, and the idea had already been discussed and was very clear in the heads of these young men. Sawah kept talking about it as we headed to Bab al-Jabiya [in Damascus] for the first meeting.”

Asked about those moments, Sawah says: “If I recall correctly, the idea first occurred to me when I, Jamil, Hassan, and perhaps Ladkani, started to think of what we could do. Could we do anything, even if it was something written on paper? I later took advantage of the fact that my father worked in printing.”

A pamphlet without a name

The friends decided that their pamphlet would remain nameless, as “a name would restrict it to a certain identity, and we didn’t want anything to restrict our freedom,” Sawah says. “What’s more, we didn’t publish regularly. Whenever an issue was ready, we would just go ahead and publish it, and so on.”

Namelessness had other legal uses, Bayrakdar says. “If we gave the pamphlet a name, the authorities would have asked about the license, and with whom it was affiliated. This is what we expected at the time, but in any case, this did not stop the intelligence services.”

The first issue was published in 1977, handed out to friends and on university campuses. It featured a set of poems and short stories, including Sawah’s story “Fadia Eats Jellies, Combs Her Hair, Dies in a Car Accident,” and Ezzat’s poem “The Alexandrian Gazelle and the Snake Charmers,” as well as a story by Ladkani titled “Here is Damascus…Here is Santiago.” Ladkani’s story used humor to “compare Syria to Chile, Hafez al-Assad to Pinochet,” Sawah says.

Publishing was rather informal, says Ezzat. “Wael and Jamil and I prepared the first three issues at my place in Baramkeh [Damascus], and the remaining issues, up till the fifth, were prepared by Wael, Jamil, Fadia and I. We typed them up on the typewriter. Then I assembled them at my place and distributed them.”

Though the four friends printed just 100 copies of the first issue, the pamphlet was a success. They’d go on to print as many as 500 copies of later issues.

“We were surprised by the turnout,” Sawah recalls. “Each copy cost one lira, but some people paid us two. I remember that the poet Ali Jundi paid us five liras as a kind of support and encouragement. We felt that we were attracting a high turnout and decided to expand the issue and the editorial family as well. Ladkani joined us, and along came Bayrakdar and Bashir Bakr, followed by Riadh Saleh Hussein and Khaled Darwish, so we became eight.”

Asked about the fact that she was the only woman on the team, Ladkani says, simply, “being the only woman means nothing to me at all.”

Publishing the unpublishable

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

From Ottoman Syria to Argentina

02 August 2021

The pamphlet’s editors had no real office. They met in artists’ homes or local cafes. They would exchange the materials they had and then decide what to publish. “Then we’d hold another meeting to discuss problematic items and agree on whether or not to publish them after a vote,” Bayrakdar tells SyriaUntold.

Printing was the trickiest part of the process. How could they put together a pamphlet living under the Baath authority, and circumvent censorship? Which printing presses would even dare print it?

“The pamphlet published two or three of my stories,” Ladkani told SyriaUntold. “I now remember the title of the first, which was ‘Here is Damascus...Here is Santiago.’ I kept all of my copies of the pamphlet, though later left them on a shelf in my family’s house in Shura [Damascus]. I looked for them once when I was on a visit to Syria, and the shelf told me: Everything fades, everything goes away. (But does it really go away?)”

Throughout its short life, a smattering of intellectuals, writers and poets published in the pamphlet, including Riadh Saleh Hussein, Mamdouh Adwan, Ali Jundi, Khaled Darwish, Ali Kanaan, Adel Mahmoud, Salim Barakat and Mahmoud Shaheen, whose story "no one else dared publish,” recalls Sawah. It was the first story Shaheen ever published, after which he rose to prominence.

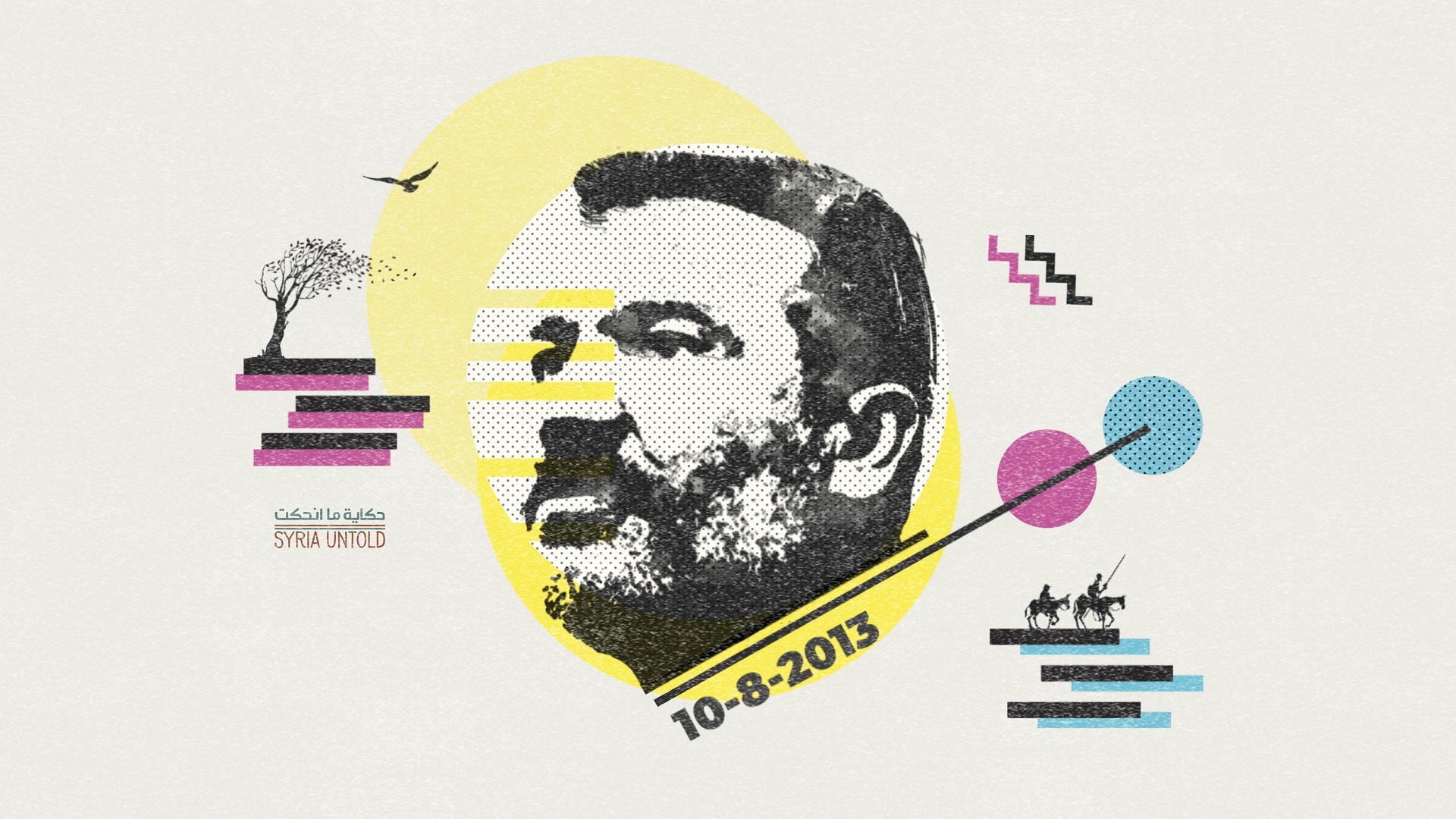

“Also in the pamphlet, Riadh Saleh Hussein published his first poem, ‘Destruction of the Bloodstream,’ which provoked an uproar,” Sawah says. Ostensibly about a young, “barefoot” love, the poem was composed of a newer, simpler Arabic rarely seen before in Syrian poetry.

“Readers were sharply divided,” according to Sawah. “Some welcomed the poem while others rejected it. Its opponents described the author as a heretic, lining up a set of words into blasphemy. Meanwhile, its supporters were amazed by the poem's warmth, simplicity and tremendous ability for impossible clarity.”

‘A new vision’

Potential trouble came when the pamphlet editors went to the library to print new issues. To convince the university libraries to let them print, they’d pretend the papers were for a student thesis. But other printing presses knew they were lying and refused to print, so they had to look elsewhere.

Ladkani says she had an important role at this stage of the pamphlet’s life. “By sheer coincidence, life entrusted me with another role that was both major and technical. I would typeset the pamphlet, taking advantage of my job as a typesetter at an official institution. Not only that, but I also used their silk paper printing device, which was widespread at the time.”

Then came distribution. “We would send copies of it to Aleppo and to the university there. Hussein and Darwish would take the copies with them,” Ezzat says. “The pamphlet began to spread and some people worked to prevent it. At the University of Aleppo, the Student Union tried to stop its distribution.”

However, these attempts failed to hinder the distribution of the pamphlet. The result: a creative shift in Syrian writing. “The pamphlet was the first to present the new type of poetry. We were not promoting art for the sake of art, and we were not promoting a theory of obligation—instead, we were somewhere in between…We presented a new vision for the prose poem.”

Ties with the League of Communist Action?

The first issue of the pamphlet came out just a year after the 1976 birth of the League of Communist Action (subsequently the Labor Communist Party). Because several of the pamphlet’s founders and editors were members of the League or otherwise close to it, some readers established a link between the League and the pamphlet—a link that the editors deny.

Media and Palestine: Times are (maybe) changing

02 July 2021

“The party had nothing to do with the pamphlet,” Sawah argues. “The people in charge of the pamphlet were culturally at a distance from the Labor Communist Party even if they were politically involved the party…The situation between the pamphlet and the League was similar to that of a painter with their father who wanted him to be a lawyer, but at the same time was happy with his son’s artwork.”

Meanwhile, according to Azzet, “some other parties, such as the Syrian Communist Party led by Khaled Bakdash, tried to support the pamphlet provided they contain it.”

“I cannot answer for each and every one of us,” Ladkani says. “The pamphlet was not a political party or movement, nor was it a circle preparing itself to join a party. But it is certain, as always, that there is an umbilical cord linking the political, cultural, social and societal aspects together. Sawah, for example, was secretly working with the circles that would create the League without uttering a single word about it. Riadh Saleh Hussein was on intimate terms with literary and artistic circles who had a different, albeit close, political inclination.”

‘The interrogation was all about the pamphlet’

Despite it having no official ties with the League of Communist Action, authorities took notice of the pamphlet. “After eight issues, the mukhabarat arrested Riadh Saleh Hussein and Khaled Darwish,” Bayrakdar remembers.

“When they were released two weeks later, they told us that the interrogation was all about the pamphlet: how and where it was printed, who financed it, etc. Riadh and Khaled were not concerned with such matters,” according to Bayrakdar.

Was Riadh Saleh Hussein predicting the pamphlet’s fate when, in its first issue, he wrote the “massacre of the alphabet”?

The sound became a whip

and the hat, a shoe

the gardens, hospitals

and love letters, time bombs.

Where do I begin?

You said: Begin with the massacre of the alphabet!

“We had long discussions about what we would do,” Bayrakdar says, remembering the period of the arrests. “We ended up deciding to continue publishing the pamphlet.”

Rateb Shabo: ‘Politics disappears amid violence’

17 September 2021

Hala Abdullah: 'I believe in cinema as a means of resistance’

11 June 2021

But soon, Bayrakdar also faced arrest. “After we published the ninth issue in the summer of 1978, I was arrested by the Air Force Intelligence…My experience with the detention and the torture that I endured was more severe than what was commonly practiced.” He remained in detention for four months.

Bayrakdar wasn’t sure if his arrest was due to the pamphlet or for other, more political, reasons. “I was asked about the pamphlet during the interrogation and they addressed me as al-Buraq, my pen name. I tried to restrict the matter to myself alone in order to shield Riadh Saleh Hussein and Khaled Darwish. What helped was that Hussein and Darwish didn’t know anything about the pamphlet printing process. The security division was easily convinced, as I told them that we wrote it by hand, and then we printed it. The fact that there was indeed an issue written by hand played in our favor.”

That handwriting was Ladkani’s. SyriaUntold asked her about the reasons the pamphlet stopped being published around that time. “Sawah was wanted, and he lived undercover in Damascus and then in other cities before Beirut embraced him. Bayrakdar, who had previously been arrested in Homs, was arrested again, apparently due to the pamphlet. Hatmal was also arrested.”

When Bayrakdar was released, the investigator warned him against publishing again. The editors held a meeting, where they decided to “stop the pamphlet because we are not a political party to fight,” Sawah recalls. “Especially after we witnessed the beatings that people were subjected to.”

He adds: “The authorities were annoyed by the pamphlet because they feared that it would be a prelude to other steps forward in the name of literature, arts and culture.”

Those involved in publishing the pamphlet remain proud of their work. “I definitely have no regrets,” says Ladkani. Everything I did contribute to the person I am today.” For her, the pamphlet became a small part of her own identity. “Since I didn’t want the name that my parents gave me to appear in the personal status records, I wondered and asked about the pen name I should use. I remember that meeting very vividly…During that session, I recalled the title of a story that Sawah had written, inspired by me. It was published in his first and last collection of stories: ‘Why Did Youssef al-Najjar Die?’ He told me that he had based the name of the main character in the story on my birth name: F. A. T. I. M. A = F. A. D. I. A. At that meeting, I shouted: I found it! People will henceforth know me by that name, and it turned into a name that even my mother ended up calling me!”

For his part, Sawah says: “The pamphlet is a project of pride for me. It is a revolutionary step in the artistic and political sense. But first, it is revolutionary in the artistic and cultural sense. I am also proud that Mahmoud Shaheen and Riadh Saleh Hussein became famous thanks to the pamphlet, which played a role in introducing them to the literary community. This is not to mention that the pamphlet connects me emotionally with the friends of that beautiful time who passed away early: Jamil Hatmal and Riadh Saleh Hussein.” The latter wrote in his poem “The Destruction of the Bloodstream” in the pamphlet’s very first issue:

O country armored with moon, desire, and trees,

Isn’t it time you arrived?

O country filled with destruction and hard currencies

full of corpses and beggars,

Isn't it time you left?