Read this article in the original Arabic here.

It was after midnight, and my hands were shaking when I woke up from a terrible nightmare. In it, I dug a rusty sickle into the neck of a man whose face was obscured. I stabbed him repeatedly to cut off his jugular veins, and the blood gushed out. It stained my face and tainted everything red.

The sky was painted black and white. It shrunk and turned into a long, dark tunnel through which the man with obscured features walked. From over his shoulders, a yellow light shone on a soiled wall and made it look cheap and flawed. I leapt towards the man, aiming for his neck, and stabbed him with a sickle. When he fell to the ground, I realized he was the warden who had tortured me in the mukhabarat’s dungeons.

Like all other survivors of detention, I have spent my days escaping in my nightmares and dreams since my imprisonment and horrendous torture. It took a fearful awakening each time to save me from the pain.

Prison: Writing versus experience

27 February 2020

Murder: a legal or ethical matter?

I read Crime and Punishment 13 years ago, during my only year of legal studies, whereby the course on criminal sanctions supposed crime to be a matter only a lawyer could solve. I never imagined since then that murder would become one of the thorniest issues in the tragedy of the Syrian revolution. The mass murder committed by one party against the other was a legal, rather than moral, matter that required extensive criminal scrutiny, press reports and testimonies, and this unprecedented documentation of crime was a mere procedural matter.

We know the criminals, but we cannot convict them. Even if we could, justice would not necessarily be served. Conviction is a descriptive matter that can carry different perspectives. Professional criminals can understand the ambiguity of conviction when it comes to crimes. The law does not seek to eliminate crimes, but to regulate them. The state is capable of defining and condemning crimes, and it has the power to activate conviction and turn it into procedural justice.

Like all other survivors of detention, I have spent my days escaping in my nightmares and dreams since my imprisonment and horrendous torture. It took a fearful awakening each time to save me from the pain.

Debatable questions: Did you see the killer yourself?

Points of contention about murder are as old as the revolution: 10 years. Perplexing questions have been asked about the victims of the crimes. Did you see the killer yourself? Did you see who killed them? Can you prove the date when the crime occurred? Can you prove where the scene of the crime was? Were the murdered people really killed in detention centers? How can we prove how and what time they were killed? Who carried out the murder? Was it the officer? The warden? The shabiha?

On revolution and civil war in Syria

18 March 2020

Human rights and civil society organizations, as well as government institutions, have asked those affected by different degrees of crimes to prove them. With the worsening of the crimes committed, different questions are formulated. Even influential states have sought to condemn the crimes, but punishment has always clashed with other technical questions, which has prevented action against the crimes.

What is murder?

With all the crimes committed since the onset of the revolution, murder has become a vague matter. What is murder? It can be defined as forcibly taking away a life, either deliberately or accidentally. But, what omnipresent life component makes murder such a terrible matter? What is the motive pushing us to defend life? Life, as a cognitive pattern, makes us realize that our existence is an exceptional opportunity. Creating language has helped us understand the rarity of the historical moment in our universal context. If life has meaning, and this meaning pushes us to the extreme degrees of freedom in understanding it and personally creating it, then killing this meaning would be one of the worst methods of control practiced by regimes across the world over people’s lives. But fascist regimes can take this extortion even further by killing the physical and intellectual meaning.

Murder turned into an act of self-defense, in which the regime and international community embarked on a selfish battle of describing the crime using terms such as civil war, the two-party war and the conflict.

While in detention, I always wondered why the warden insisted on torturing the inmates with such brutality. What pushes the warden to prolong the pain and stall in executing it? Why doesn’t he hasten it to eliminate his opponents once and for all?

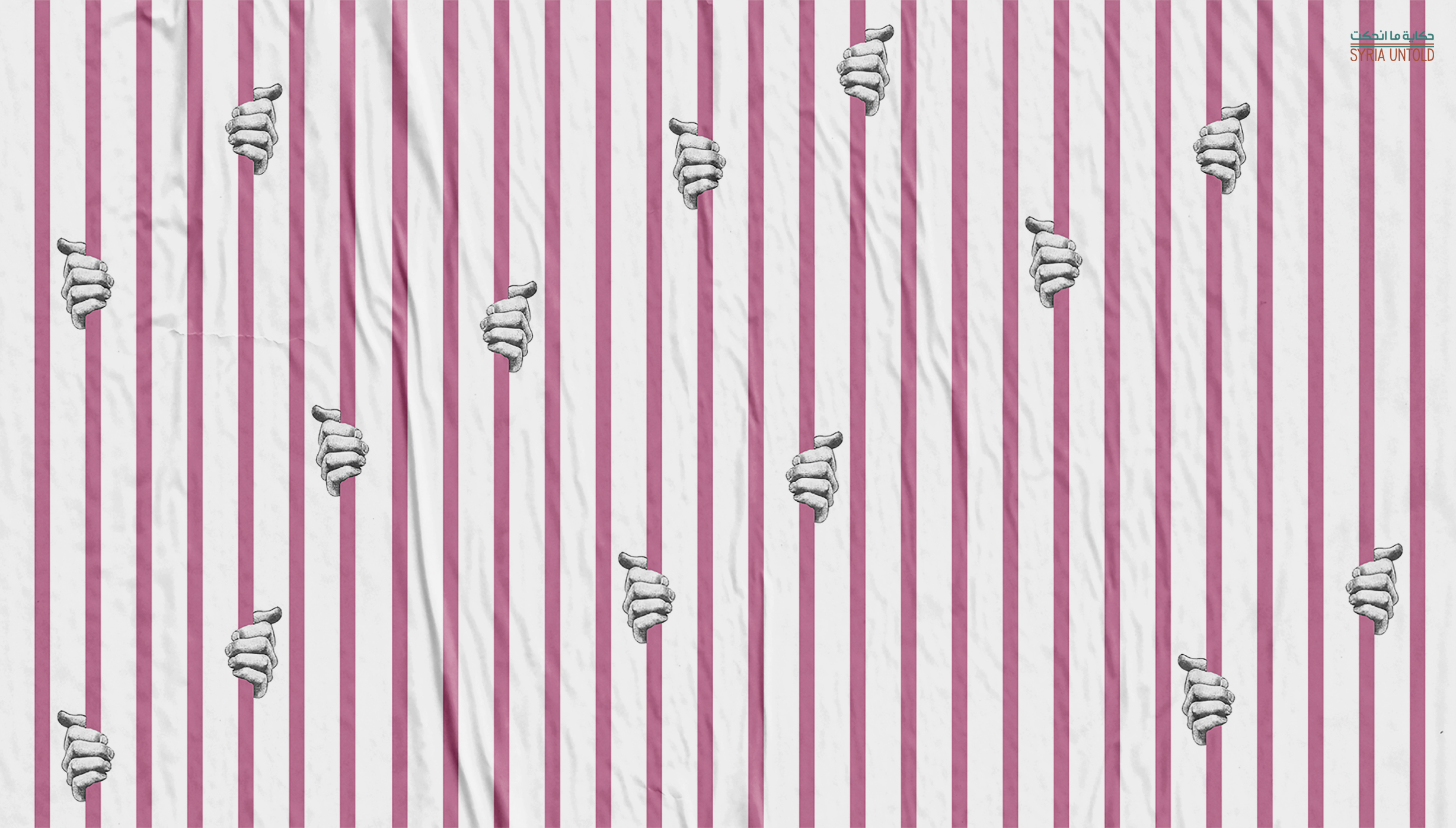

All those horrible leaked photos of the heinous killings through torture essentially aim at destroying meaning. This is what the media and internet do in describing crimes. Depicting images and videos of the crimes plays a desensitizing role. The regime tries to kill the internal meaning within the detainee, then kills the meaning within the families of this detainee and the public following up on the murder in all its forms, thus transforming the meaning of owning freedom to the meaning of stealing life. Desensitization to crime as it becomes a familiar act is actually one of its elements. Therefore, we are all partners in the crime, and we eventually lose interest. The hand of salvation extended to us all from heaven will be cut by our personal desire for survival from that hell, at the expense of others.

An unaccomplished trial

In the wake of the peaceful protests, it seemed evident that the trial for such crimes would not take place. With the continuing escalation of murder, this implicit fact completely shocked many of those involved in the revolution. Ever since crimes began eluding their legal definition internationally and the trial proceedings that necessitate stopping this amount of organized criminality, to say the least, it has become clear that the confrontation is with a totally depraved gang.

As this gang having a legal existence under the name of a state launched airstrikes on rebellious neighborhoods, justice took on an extremely surreal form. A heated debate about the definition of crime raged on in Syria, as some insisted on a peaceful track that meant total surrender to the crime, while others argued the case for individual justice to the detriment of legal justice in Syria or internationally.

At that point, murder turned into an act of self-defense, in which the regime and international community embarked on a selfish battle of describing the crime using terms such as civil war, the two-party war and the conflict. Consequently, the main crime was cleared, not by prescription, but because of its description.

The first crime

I can still recall the first crime I witnessed clearly. I find myself always reminding myself of it, to place murder in its irregular context and extract it from the vagueness that has surrounded the crimes committed since the onset of the revolution.

Under the gray March sky, while thousands of young protesters cheered, as though they had just risen from death and stepped into the light of freedom and life, a young man in his 20s was shot with a Russian-made Kalashnikov. With the butt of the machine gun resting on some shoulder, cold-heartedly and with complete clarity on all state levels, the order was given to shoot. The bullet penetrated the man’s thin figure, perforating his stomach, and he fell to the ground. Blood gushed out of the small hole in his body. He looked at my face, as I was right next to him on the ground. He lifted his eyebrows with a childish shock and confusingly dragged his head on the asphalt. He did not understand why this happened, and neither did I. The gentle features of his face turned pale. He was a young man in his 20s with tanned skin, a light moustache and dark black eyes. He closed his eyes and gave out his last breath.

The man was killed.