A version of this article was first published in Arabic here.

“Sudan used to treat Syrians as it treats Sudanese people in its official [government] departments, schools and universities. Living and working in Sudan did not require any official residency papers. Besides, the Sudanese people were very kind to Syrians,” says Seif, a Syrian man who has been living in Sudan since 2013 and holds Sudanese citizenship. He requested a pseudonym to protect his identity.

For years, Sudan was one of the few countries Syrians could travel to without first obtaining an entry visa. Unlike in other countries where Syrians sought refuge, in Sudan they had the right to work, education and hospitalization. Syrians opened businesses and, for the most part, went on with their lives.

Residency and citizenship were relatively simple, too. Sudan’s 1994 Nationality Act granted citizenship by naturalization to foreigners, including Syrians, who had resided on Sudanese soil for at least five years. However, many Syrians who arrived after 2011 obtained Sudanese citizenship through a direct decree from former president Omar al-Bashir. Bashir was later ousted in the wake of a popular uprising in 2019, and the country adopted a new transitional constitution.

Still, as Syria’s war raged on, Syrians flocked to Sudan, their numbers peaking in 2016. According to official figures, around 100,000 Syrians currently reside in the country, while media outlets estimate a higher number. Some reports indicate that around 300,000 Syrians live in Sudan, likely because it became an attractive destination after 2014, when Turkey, Egypt and Lebanon became harder to access. Official paperwork in Sudan was oftentimes easy, and Syrians felt they were treated kindly. Wealthier Syrians could also buy into a thriving black market for Sudanese passports.

That reality will soon change. In December, Sudan’s Ministry of Interior issued a decree to strip certain naturalized citizens of their Sudanese citizenship and to impose an entry visa on Syrians coming from Syria.

Children at war: Reliving photos of east Aleppo

25 September 2020

From Damascus’ al-Rawda cafe to Berlin’s Einstein cafe, a heartbeat

28 August 2020

What is behind these stricter measures?

Syrian honeymoon in Sudan

Sudan became somewhat of a haven in recent years for Syrians who were looking for a quick way out of their home country, and had the means to do so. They settled in the capital Khartoum, especially in the Al-Amarat, Kafouri and Morabaa al-Riyad neighborhoods, where they established restaurants, cafes and construction businesses. With time, their businesses flourished.

Bashar, a 28-year-old man from Syria, currently lives in Berlin. He lived in Sudan from 2017 to 2018 with an official residency permit, before the recent decree to impose stricter measures on foreigners residing in the country.

“The procedures imposed by the Department of Aliens [at Sudan’s Ministry of Interior] to obtain residency were easy. According to the permit, the residency duration in Sudan is one year, and easily renewable. However, Syrians still applied for Sudanese citizenship out of fear of sudden deportation decisions, especially since 2016.” By then, their residency requirement for obtaining citizenship was reduced to only six months.

Still, “many Syrians obtained Sudanese citizenship without even meeting the reduced six-month residency requirement, through bribery and favoritism,” according to Bashar.

Sudanese writer and screenwriter Hussam Hilali adds: “The former regime of Omar al-Bashir was known for its Islamist and Arab inclinations. During his rule, he facilitated the procedure of obtaining the Sudanese citizenship for Arab and Muslim figures, while he deprived refugees from African countries like Chad and Niger of the citizenship of their neighboring country.”

Seif recalls the stages that Syrians underwent in Sudan as visa restrictions gradually tightened. The year 2018 marked the first stage, he says, when an entry visa was imposed on Syrians coming to Sudan from any country other than Syria.

Then in 2020, procedures to withdraw citizenship from foreigners were rolled out, only to be suspended due to the COVID-19 outbreak. The third stage took off in summer 2020, when a decision instructing naturalized citizens to consult the Citizenship and Civil Registration Authority was issued. All paperwork related to Sudanese passports and citizenship procedures for non-Sudanese residents was then halted in governmental departments, though this halt was said to be temporary. Passport renewals were also suspended. Later, naturalized citizens were banned from traveling to and from Sudan, and finally, an entry visa was imposed on Syrians coming into the country from Syria.

Seif notes that the authorities have returned some Sudanese passports to Syrian shareholders and investors after checking them, while others are still waiting to get their passports back.

A small cafe in Damascus

01 January 2021

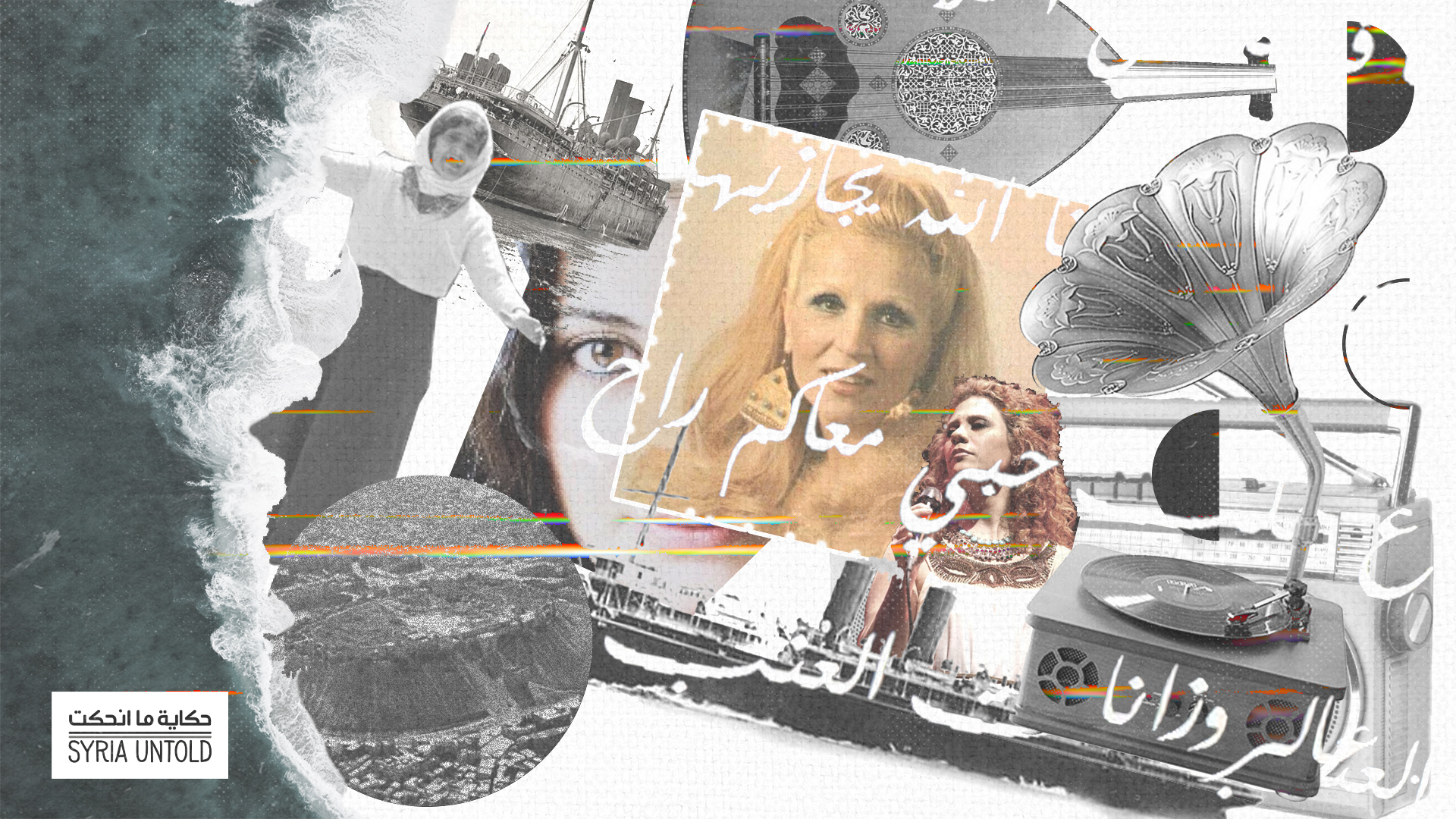

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

Why now?

To writer Hilali, the current measures are a departure from certain pro-Islamist policies of ousted president Bashir’s era. “Bashir’s regime granted Islamists from around the world Sudanese citizenship. The decision to withdraw citizenship was part of an agreement to strike out Sudan from the list of countries sponsoring terrorism, and its purpose was to ensure that Islamists and terrorists would not get Sudanese citizenship,” Hilali believes.

Several local news reports, stated that Rached al-Ghannouchi, leader of Tunisia’s Islamist Ennahda Movement, was among those stripped of Sudanese citizenship in recent months. SyriaUntold could not independently verify these reports.

According to other news reports, some Syrians residing in Sudan resorted to courts to appeal the December 2020 decision by the Ministry of Interior, while other Syrians interested in Sudanese affairs expressed their anger and mocked the decision on social media. Syrian film director Jamal Daoud posted on his Facebook page: “Sudan issued a decree [today] banning the entry of Syrians without a visa. With that, the Syrian passport does not allow us entry into any Arab country, even though it costs us between $300 and $800.”

“Syrians in Sudan are waiting for new decisions that would make their lives easy again,” says Seif, who still lives in Sudan. “Many consider themselves citizens of Sudan, the country that warmly welcomed them. Any harm to Sudan would harm them, and any benefits to it would mutually benefit them,” he adds.

“Will Syrians get what they wish for, or will Sudan join many other countries in tightening the noose on them?”