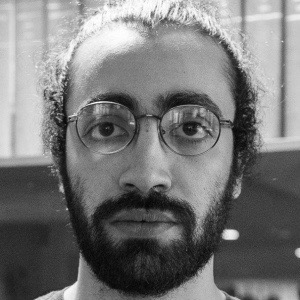

This reflection is part of SyriaUntold’s week-long collaboration with Ecologìas del Futuro on science fiction and imagining the future in the MENA region. We asked writers, artists, journalists and filmmakers from different countries across the region to send us short audio messages or reflections on the future and their relationship with it.

Scroll down to listen to this piece in its original audio format.

For a long time, neither my country nor my language produced science fiction—first because technology was not emerging from it, nor did machines completely dominate outside the production sector. Religious tales already provide clear endings for what will come next: there will be a specific moment preceded by signs and signals, after which point the world will turn upside down.

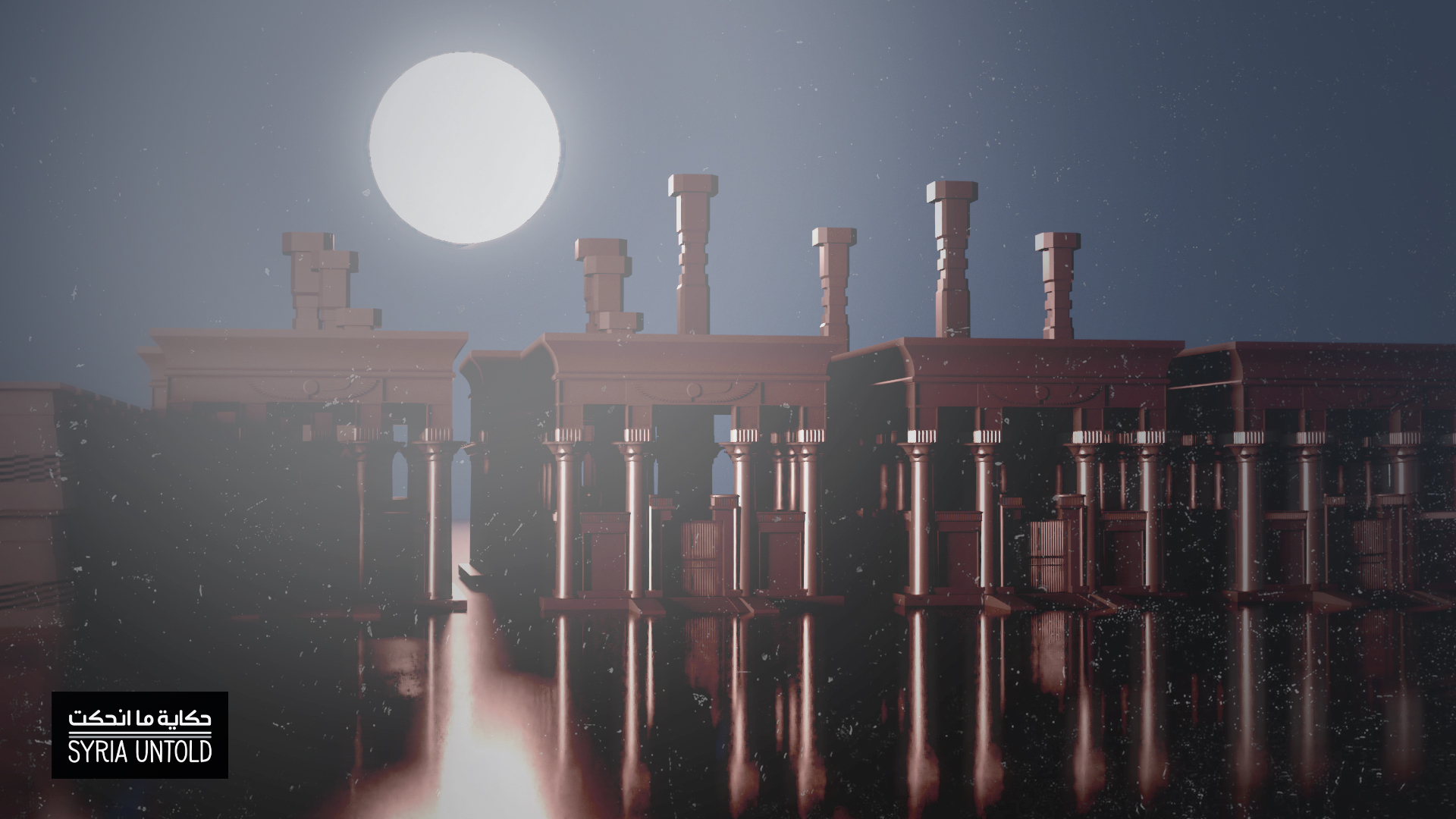

For a long time, my country, Syria, has been subjected to an exceptional state of affairs: emergency laws and state agencies that regulated obedience and methods of production, and authority violently seized against all who so much as deviated from the scenario that had already been drawn in advance.

What I imagine for the future is not a dystopia, if there is no apocalypse after which only a certain class of people can survive.

Disappointed hopes will be the cruelest end; no salvation from this world.

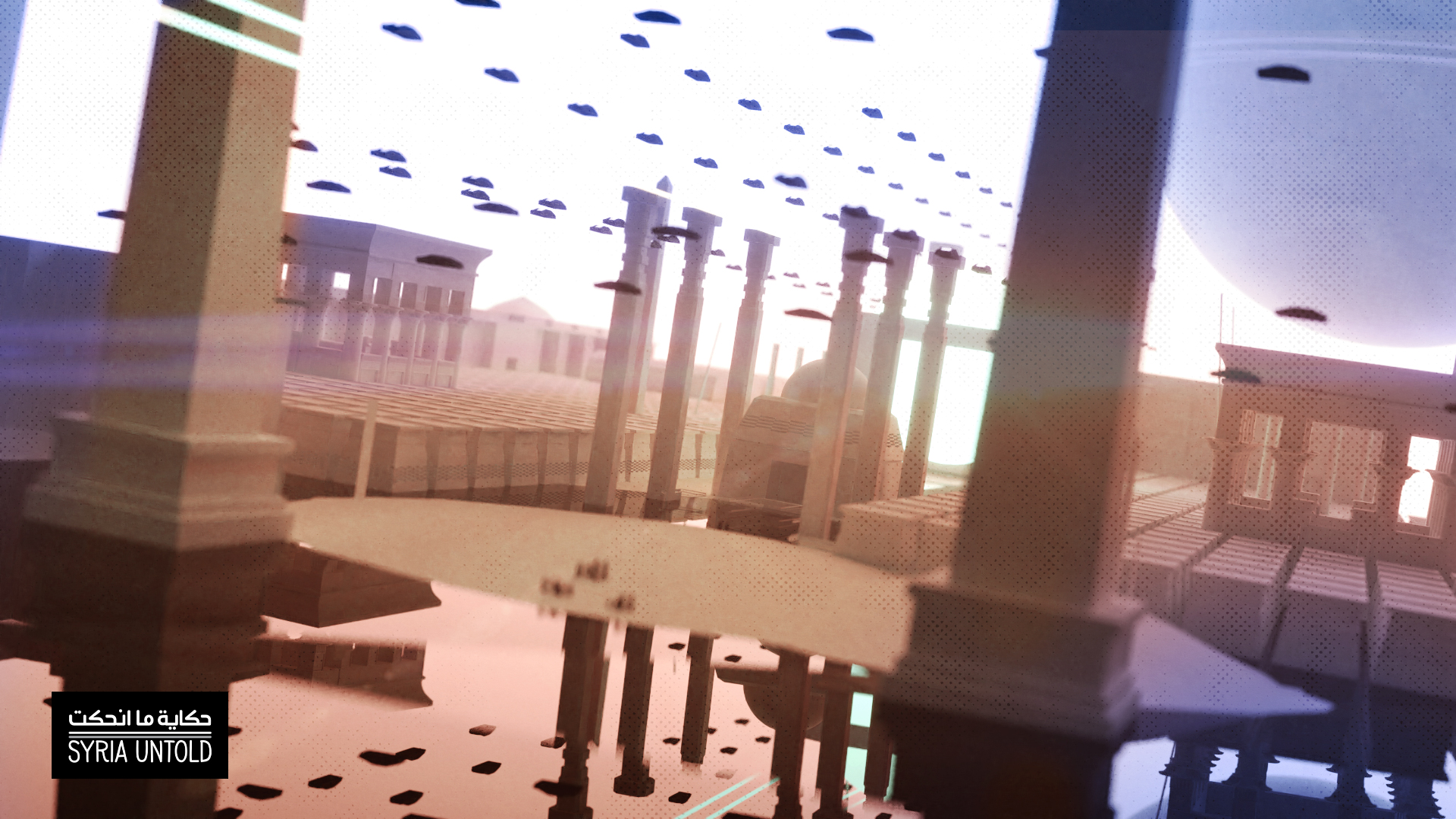

I think that if this “exceptional state” continues, then the future will be full of disappointed hopes. There won’t be more people who die, but everyone will come to resemble those who walk in their sleep, or those who dream endless waking dreams, an automatic current that controls individuals for their survival. I don’t think the end of the world will come about through some divine event or an accident that damages Earth as we know it. Rather, the survivors will be those who go on living with their missiles abroad somewhere, while the rest—the poor, the less important and the excluded—will be left to their fates.

The family will not be destroyed, and people will not devour one another. Rather, it will be enough for them to simply stare into the void.

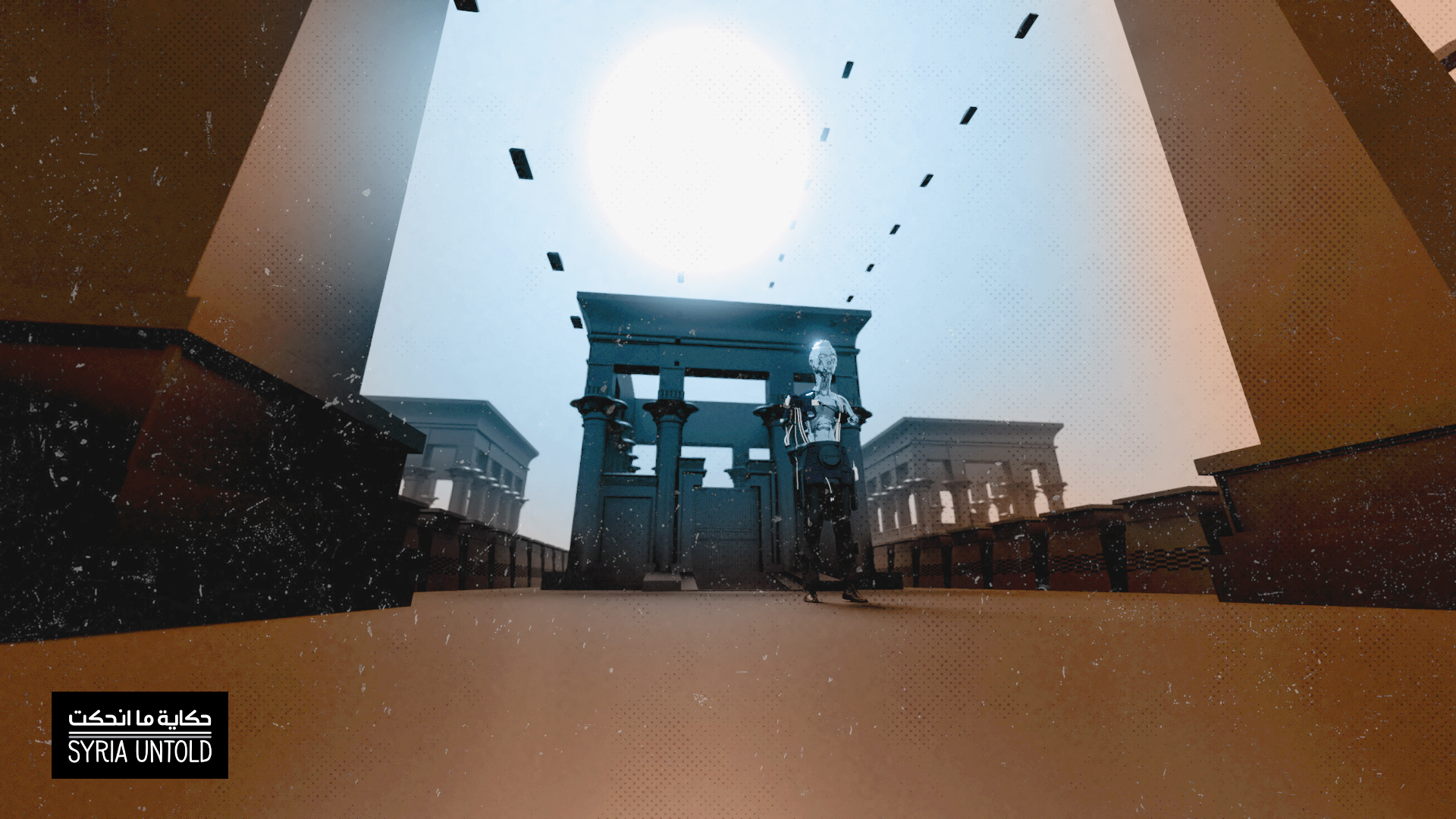

Disappointed hopes will be the cruelest end; no salvation from this world. Our current dysfunction will not change. I also think that time will become slower, especially since one of us will deplete their memories. Nothing new will accumulate but waking dreams that, according to French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, can be transmitted verbally, and not as a narrative. In the future, nobody will believe what is said.

In the novel Akhbar al-Razi by Tunisian writer Aymen al-Dabbousi, at the end of the world we are introduced to a lizard that plays the part of the psychoanalyst, not unlike French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. This lizard both advises and teases the protagonist at the same time.

Maybe after 300 years, such creatures will be responsible for our health and mental wellbeing. They are the only survivors, whether in religious tales or in natural history. They are the most capable of passing on wisdom to us. Perhaps because this Lacanian lizard, whenever she looked at her reflection in the mirror, could not believe what she saw, simply because her reflection and her stories were not her own. So she learned to change her skin, to leave a trace that she, at some moment, wanted to change what she saw in the mirror.

Listen to Ammar Almamoun's original audio recording of this article: