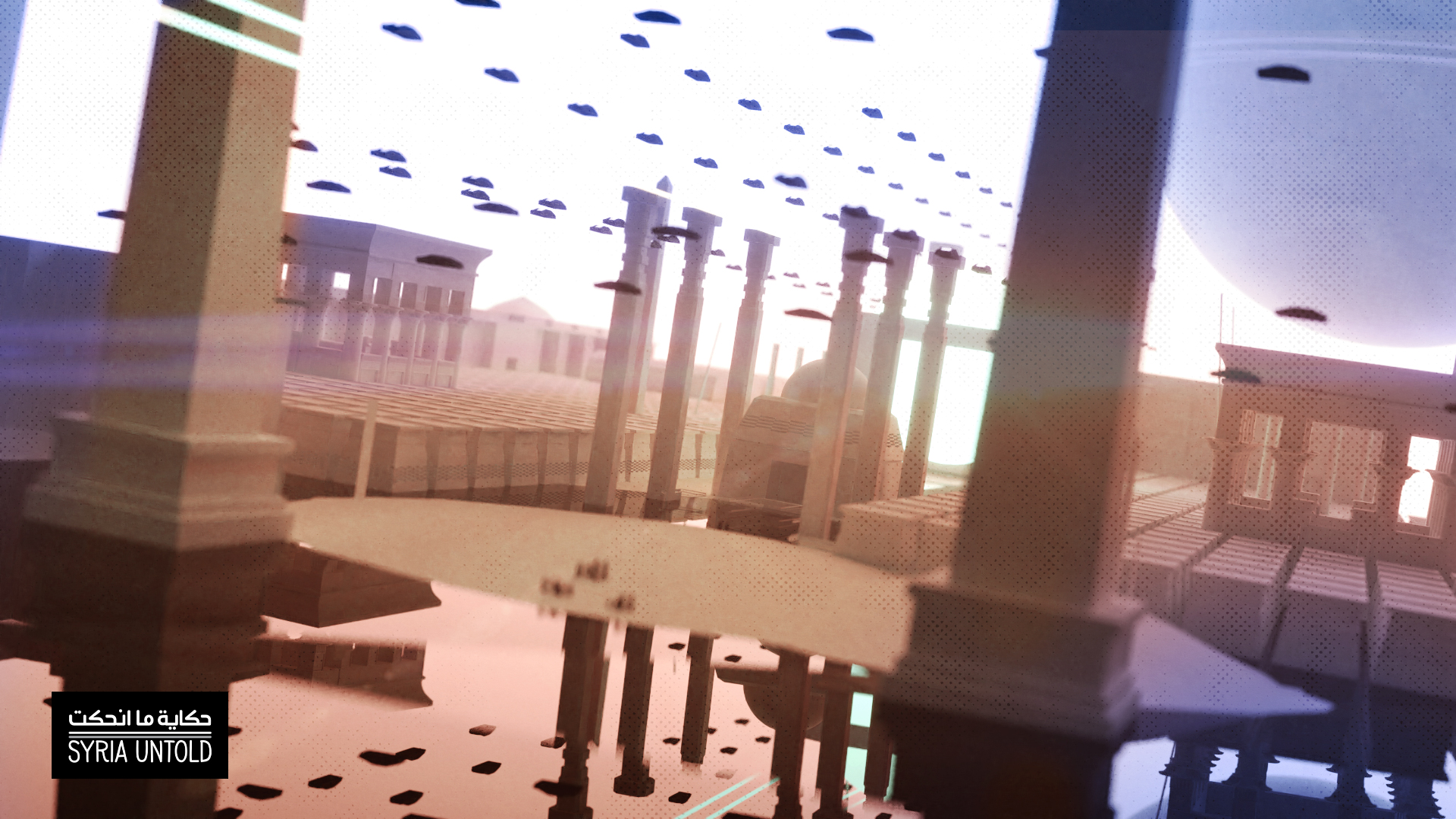

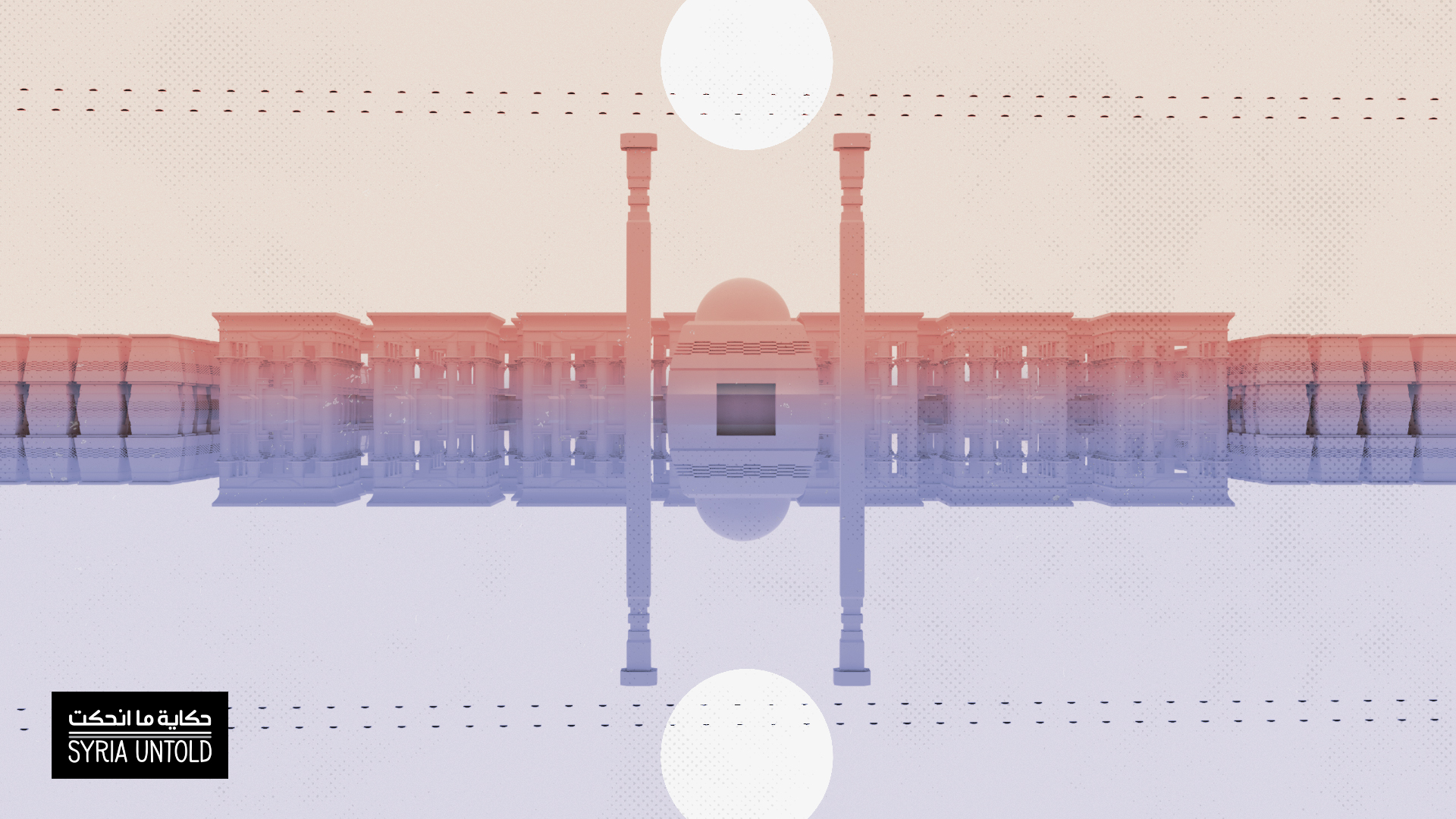

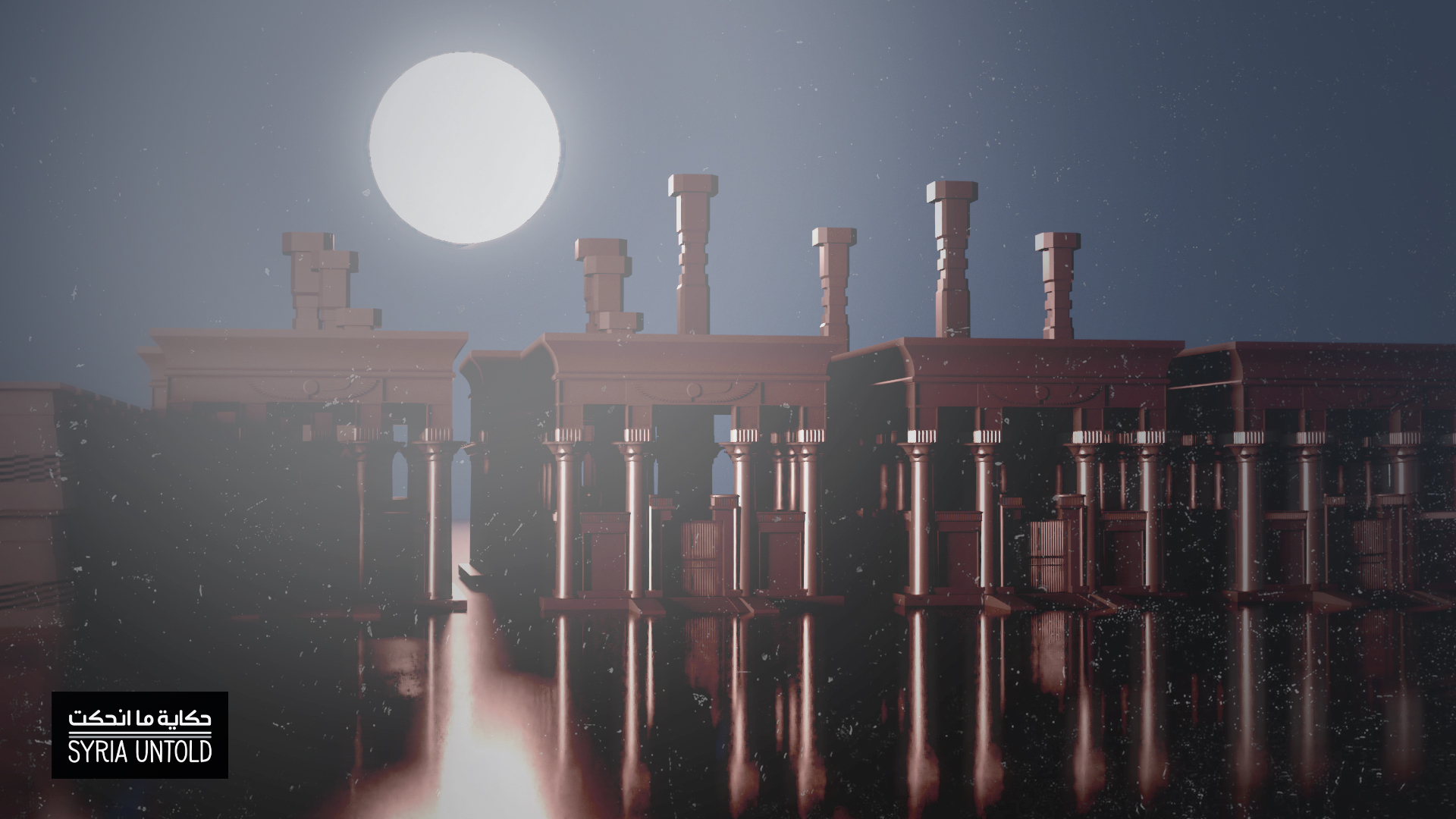

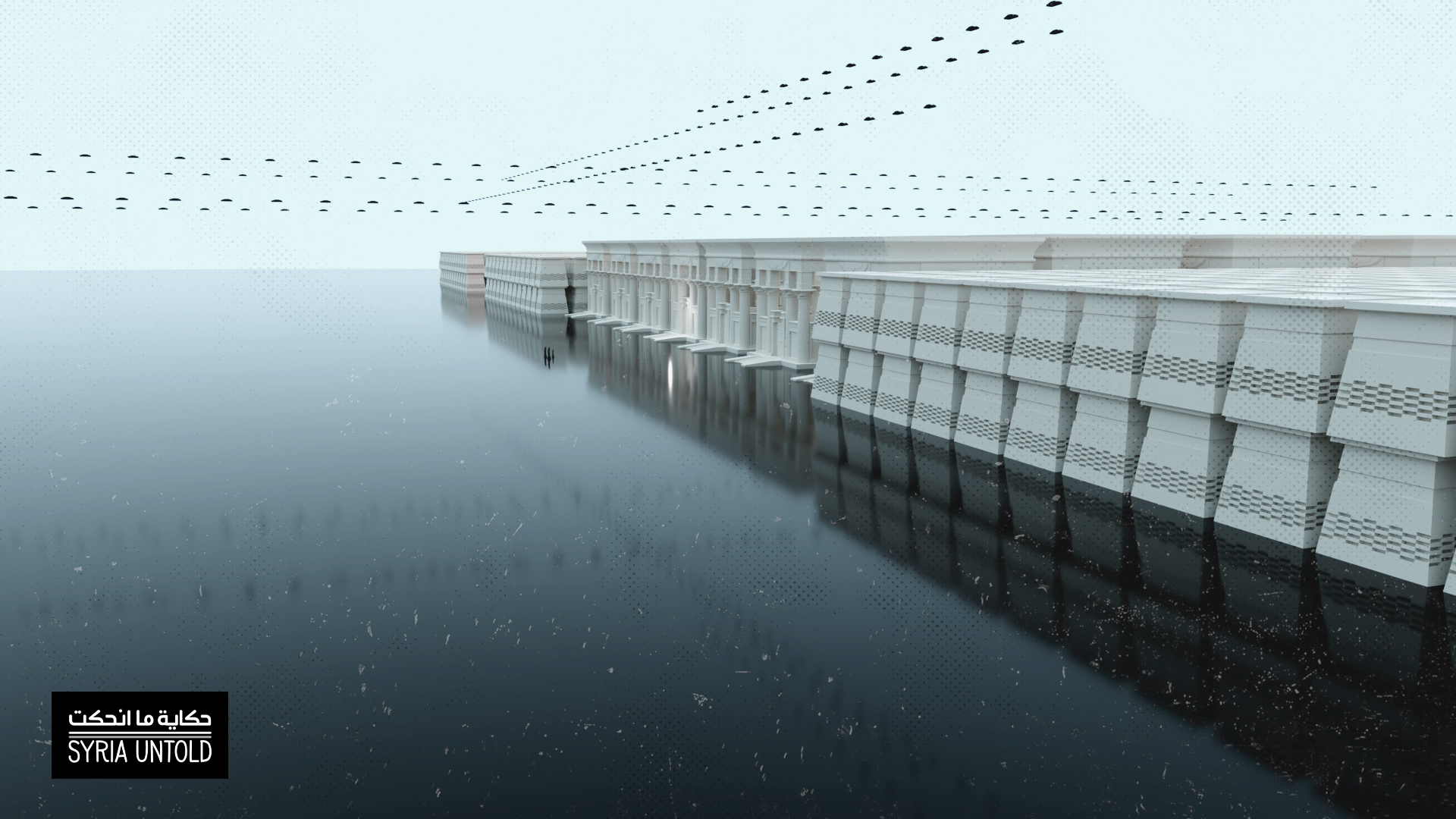

This reflection is part of SyriaUntold’s collaboration with Ecologìas del Futuro on science fiction and imagining the future in the MENA region. We asked writers, artists, journalists and filmmakers from different countries across the region to send us short audio messages or reflections on what their world may look like in 300 years, and their relationship with the distant future.

Scroll down to listen to this piece in its original audio format.

I’m only 37 years old, but as we say, things are as they are. That is, nothing has changed since 100 years ago or more. But when I think in a certain way, like someone who has lived through a war that rages on, I feel as if nothing will ever change.

Things change from place to place—this is normal. But I feel that morals will remain as they are. Or perhaps they will get even worse. The morals of the market or personal interest will prevail, or the moral concept that everything revolves around private property for one individual, one state, one political current, one flag, and on and on.

Science fiction in MENA: An artistic tool for change

26 April 2021

And I can’t imagine that education will change. Our parents tried to raise us in some sort of idealistic way, but we didn’t turn out as desired, perhaps because this is what the situation requires of us. We are now raising our own children on idealism, and not to cause harm or lie or other bad things. But as a Syrian, I feel that my future always carries a knife, and it wants you to change no matter what you actually want.

Naturally, our children will change. This is not something related to technology or that 300 years from now things will be different. Yes, there will be change, but it won’t be from us, or perhaps we will enjoy only scant benefit from these technological advancements, as they tend to say.

I don’t imagine that we will reinvent missiles or make a quantum leap for something that already exists and comes from Europe, Japan or other developed countries. At our core, we are merely consumers, people who love not to tire of anything, people who love for things to reach us without any effort on our part or any thought of creating or inventing things ourselves.

Life itself has been about the same in this region, without changing, for hundreds of years. Characters come and go and other characters take their place. The reason, of course, is death. I mean that change happens due to the idea of death; one character dies and another comes to take his place with the same form of expression, the same form of indoctrination, the same form of thinking, of education, of many other things.

Things change from place to place—this is normal. But I feel that morals will remain as they are.

Without any hypocrisy or exaggeration, I feel that this is what has happened to us as Syrians over these past 10 years of war. We need more than 300 years for its effects to finally dissipate. Is it reasonable at all, for example, how many cases of cancer have been caused by the private electricity generators, and by the fumes of the now widespread petroleum burners?

It’s impossible. Things will stay just as they are. People who listen to me may say that I’m melancholy—yes, I’m melancholy because for 37 years things have been exactly the same. It’s impossible for them to change.

One could mention Facebook, NASA, missiles, health insurance. But what about a decent life? I’d respond that we, too, have Facebook for defamation, we have NASA for destruction, we have missiles for death and we have enough health insurance to be diagnosed but not to be healed. This is not a decent life.

At times I feel that all of us in the region are living in a garbage bin. Someone comes from outside and decides for us: “This is nice garbage, it can be recycled so that it may be worse in the future.” Or: “This is not nice garbage, it has no future and we cannot benefit from it.”

This is how things are, and this will stay the same—not just for the next 300 years, but perhaps for the next 1,000. Death is death, and stasis is stasis. Everything has been frozen for 1,000 years.

Listen to Ciwan Teter's original audio recording of this article: