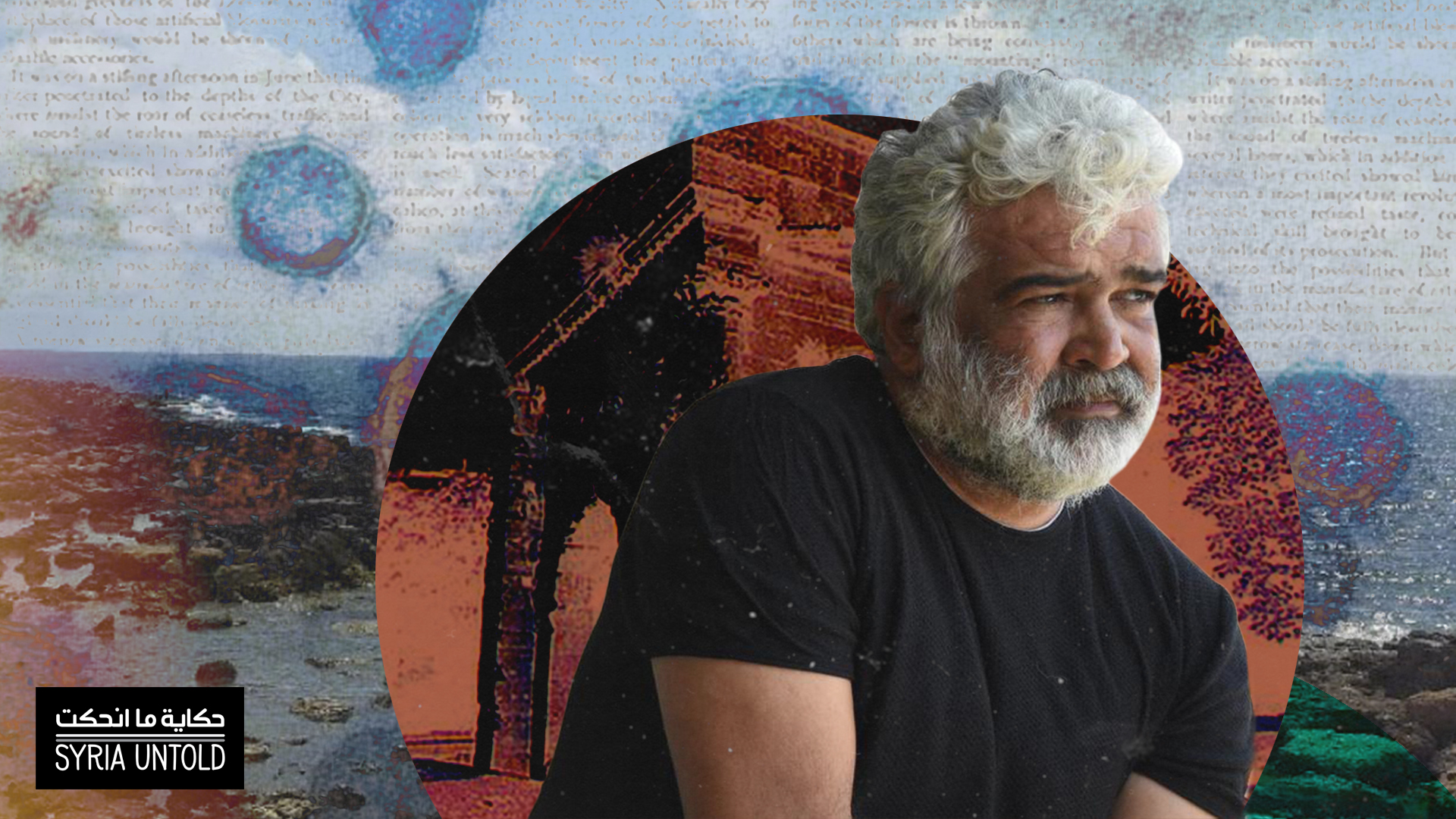

I only met writer and ex-political prisoner Wael Sawah a few times—three, to be exact. The first and second time were due to his work at the Al-Awan website, where I used to write, and the third time during a political conference. All three times, I could not ignore the political prisoner “halo” surrounding him, although he is too modest and courteous to feign such an aura. In fact, all he has done since his release from prison was try to escape that halo, albeit without washing his hands of it completely. At the time, in my youthful imagination, I idolized the idea of the political prisoner.

Now, as I recall these meetings as impartially as possible, particularly those that took place in al-Kamal cafe in Damascus, I look at Wael smoking his tobacco calmly and peacefully, like a person swallowing his anger and worries and addressing his companion’s questions in detail. He asks, speaks, gives his opinion, listens then leaves, but not before spreading an aura of warmth.

In each of Wael’s articles, I discover something new—not just due his encyclopedic knowledge of culture or his experience of activism, but also through the modesty and warmth that radiate through his writing. As I read his articles, it feels as though I were listening to him narrate them in al-Kamal cafe, with his calm voice. Isn’t that what writing is about? To give the reader the ability to imagine it as the text was written for them, that the writer is their friend? This is Wael for us. He never invested in the political prisoner halo, rather giving his energy writing, love and kindness, which I still feel since I shook hands with him more than a decade ago.

First, please allow me to express my deep gratitude to you for a personal matter as much as it is general. I want to thank you for the hundreds of articles that you published in Daraj and Syria TV, in which you spoke about your own experience and those of your friends in the Labor Communist Party.

Do you think you were overdue in writing these articles? Why write now, and not before? Before you answer, I want to be honest with you. As I was reading those articles, I would always ask myself: Why didn’t Wael write this testimony earlier? If we had known this information or these details earlier, perhaps my generation would have been more aware and realistic while battling the same dictatorship 30 years after your first struggle. Is my criticism here a mere luxury of the “intelligentsia” asking you for something that was not even possible under circumstances that were beyond your control?

Syria’s Labor Communist Party, a rich political history

16 October 2020

Randa Baath: 'Any cultural act is vital'

12 March 2021

First, I would like to thank you for this compliment. Had I known my writings would have this impact, I would have set pen to paper decades ago. But, seriously, writing is defined by two factors: one objective and the other subjective. If I had written about the topics you mentioned, regarding Syrian dictatorship and the struggle against it, where could I have published them? What consequences would I have suffered as a result?

We had to wait for the revolution to open new horizons for us to write fearlessly about the past, present and future. Arab and foreign media outlets opened their arms wide to Syrian writers after the revolution, and the digital revolution and abundance of websites where we could publish helped us push through.

Still, another reason prompted me to write about the experience of the Syrian Left in the 1970s and 1980s. The revolution bred a generation of exceptional activists who overcame their fears and faced the bullets with their bare chests. They created methods we were not familiar with, then they drew their independent path, politically and intellectually. But what really caught my attention is that they thought they were flowers blooming in the desert and that before them, Syria did not know any activists who worked in politics, fought the regime and paid the price by spending decades of their lives, if not their whole lives, in prison. For that reason, I contemplated the idea of telling the story of the Syrian Left to introduce Syrian youths to their political activist predecessors.

But there was also a subjective, personal factor. I wrote about the Syrian Left in the form of memoirs, and as you know, one does not think of writing their memoirs until they have finished the actions they will then write about.

As I’ve kept abreast of your writing and activism, I noticed something both beautiful and exciting: You know many Syrian intellectuals and have direct ties with them, while you also know many political actors. How have you managed all these relationships? Does that stem from an intertwining political and cultural interest? Or are the Syrian cultural and political spheres generally that interlocked?

I was lucky enough to meet a large number of exceptional people from the cultural, artistic and political circles. I lived with them, was influenced by them and learned from them, from Muthaffar al-Nawab, Ali al-Jundi, Mamdouh Adwan and Hazem Saghieh to Mohsen Ibrahim, Talaat Yaacoub, Gilbert Ashkar, Afif al-Akhdar, George Tarabishi, Sadeq al-Azem, Saadallah Wannous, Mostafa al-Hallaj, Farhan Bolbol, Fateh al-Mudarress, Mutasem al-Dalati, Saad Yakan, Sheikh Jawdat Said, Hani Fahs, Father Elias Zahlawi, Khalid Bakdash, Riyad al-Turk, Jemal al-Atassi and Edward Hashwa, among others.

I have to admit: I think I have a double personality. When I am in the company of artists and novelists, I forget about politics and politicians, and as soon as I take up a political activity, I forget the intellectuals and novelists. When I go to a concert or see a new play, I forget everything else.

Honestly, I have been somewhat opportunistic. I learned from everyone without having the capacity to teach them in return, due to the difference in age, experience and knowledge. The poet Ali al-Jundi once asked me, “Why are you always silent?” I said, “What can I possibly say in your presence, Ali?”

Thanks to my relations with these people, I acquired philosophical and cognitive depth, a literary and artistic sense and wide political experience. I know many ardent activists who do not know even one poem and who have not seen one art exhibition. I know great poets who do not care about the life around them and are not familiar with any political parties or theories.

I was neither an ardent activist nor a great poet, but I had a taste of each of these worlds. I can say that this molded my personality in a totally different way from other people in my generation.

I learned two things from my father: the Arabic language and democracy.

You began your journey as a storyteller, then politics stole you away and led you to prison. After your release, you continued your activities in a tight circle of politics, culture and civil work. Where do you find yourself more? When you look back at your life, what do you regret?

Yes, I started out as a storyteller. When I was 21, I won first place at the Okaz Festival at the University of Damascus. At 23, I published my first collection of stories, entitled Why did Youssef al-Najjar Die?

I then sacrificed literature for the sake of politics. Political work and struggle had a certain charm. There was a romantic veil which covered the pursued and wanted person moving from house to house and carrying a fake identity. All this made me feel I was destined for something beyond literature. Abu Samer [Aslan Abdul Karim] told me, “You have given up what is less for the sake of the more supreme. You should not be sad.” I had told him that I was no longer able to write stories and poetry. The last story I wrote was in 1978, then my pen ran dry.

Syria’s Labor Communist Party, a rich political history

30 October 2020

Syria’s year of pain, through the eyes (and pen) of Khaled Khalifa

21 November 2020

I mastered the skill of moving from one place to another, from one friend to another and from one apartment to another. Abu Samer believed politics transcended art. I was happy with his remark, and I felt an overwhelming satisfaction. “I had moved from below a certain level to well above it, to a good place,” I would always repeat to myself when I longed for the pen and paper. But this was just an illusion. We were living beautiful dreams and illusions, only to be awakened by security reprisals that would take away some of our friends as a reality check for a while. We would then sink back into slumber, to dream of a new world free from hatred, violence and prison. Somewhere in between humor and seriousness, we would distribute roles amongst ourselves. My friends awarded me the portfolio of culture and media, and I was happy with the idea.

Still, my awakening came early. When my friend Faraj Birqdar insisted on embarking on a political journey through the League for Communist Action, I tried to spare him as much as possible. I did not want Faraj, who was one of my favorite poets, to give up poetry for politics. I told him, “You are a poet, so write. There are hundreds of men who can distribute data, but there is only one poet called Faraj Birqdar. My duty is to protect that poet in you. Each poem you write is worth more than a thousand political statements and benefits the revolution a thousand times more.”

When Youssef Abdelke was released from prison in 1980, I was tasked with notifying him that he was chosen as a member of the expanded central committee.

I was against this opinion. Youssef’s real mission was not one of daily activism and escape from security. His was a mission of painting, sculpting and art. He was trying to travel to Paris to study at the School of Fine Arts. Still, I had to relay the message to him. I told him, “I have a message for you from friends. They want you in the central committee.”

I then fell silent as I looked into his eyes. I wanted to make sure he understood the message. Then I asked him, “Do you understand what I am saying?” He answered, “Yes!” I added, “My personal opinion is that you ignore this message and continue your project to travel and study in Paris. As an artist, you are much more important than 10 revolutionaries combined.” And this is what happened. In fact, I became “like that crow that tried to imitate the partridge but forgot its own walking style in the process.” Literature slipped away from my hands, and I did not achieve anything in politics.

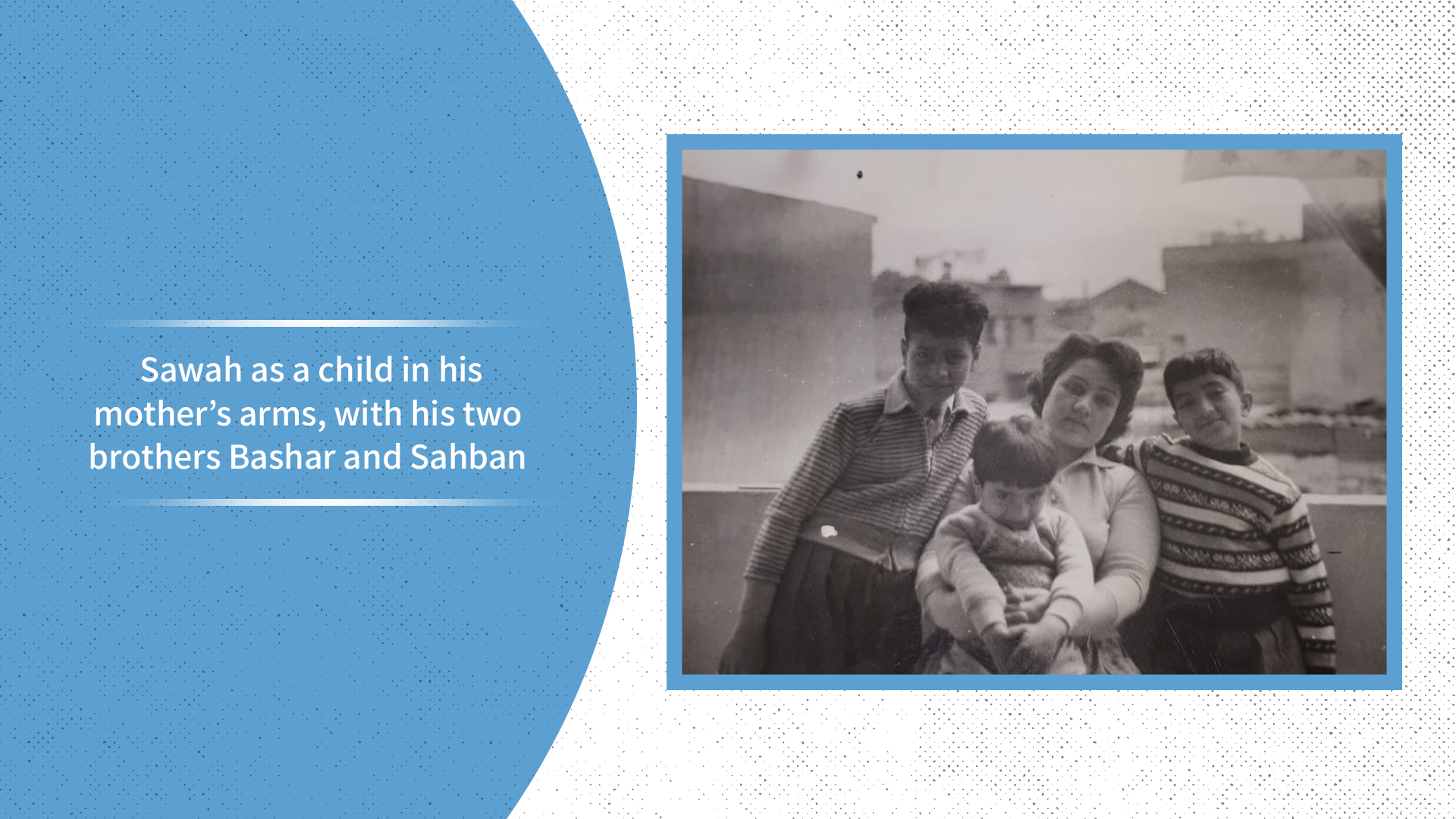

Your father was politically and culturally active in Homs. Your eldest brother Firas is a renowned researcher and intellectual. Your other brother Sahban is a cultural activist and publisher, and your nephew Amr is a scriptwriter. My question is: What did this family offer you? What does it mean to be born into a family with such interests in public affairs and culture? Did this ever limit you?

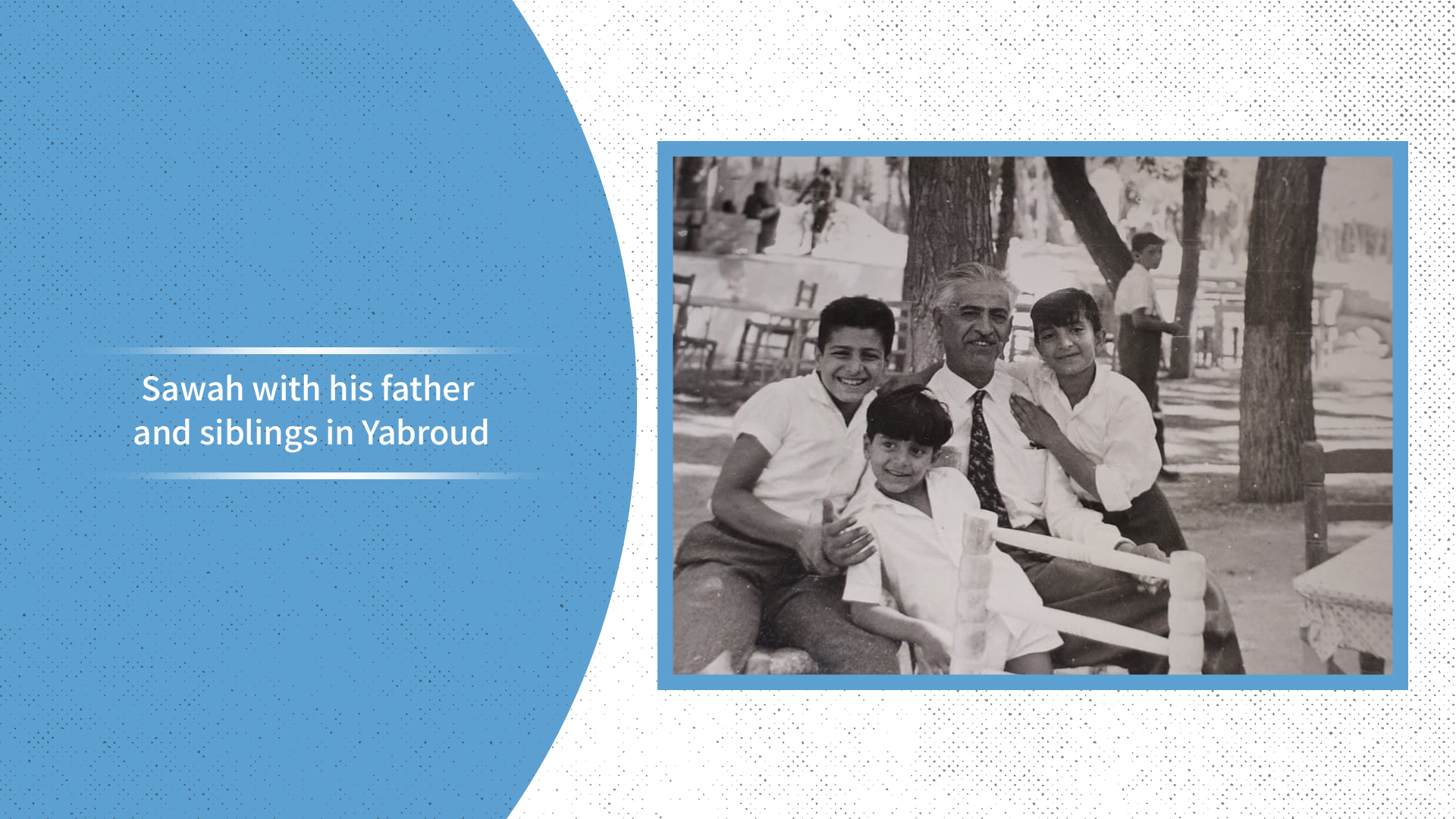

I am the youngest of my siblings. My father and brothers had a huge impact on me. As soon as I opened my eyes to this world, I saw books, newspapers and magazines around me. I was only six when I would go to the media campaigning office of my father and prominent leader Hani al-Sebai from Homs during their parliamentary electoral campaign. When I was eight years old, I would see my father, disguised, leaving the house at dawn to flee the Baath coup. At our house, you could find volumes of his daily newspaper, which he began issuing in 1948. I learned two things from my father: the Arabic language and democracy. Arabic remained my biggest love, while democracy was my most sacred ideal, even at the most radical times in my life.

My brother Sahban was a huge influence on my perspective and my way of life day by day. Bashar was my political advisor, while Sahban was my cultural and literary advisor. Sahban taught me how to write stories and allowed me to help him publish his first stories. I learned gracefulness in expressions and strength in words from his stories, and how to turn a sentence into a light breeze that enters the soul without permission. Armed with his radiant smile and deep laughter, Sahban coped with life’s hardships. Through his courage over three wars, he understood that any cause has a price that one must savor in paying. In 1967, Sahban was injured when he left university to defend the capital. Baathists sent him without training or cover to the frontlines, where he was wounded in the foot. During the Black September, he entered Jordan to defend Palestinians, and in 1973, his tank was targeted. Shrapnel left scars all over his body, and some of it remains in his neck until this day.

Sahban is not a man of politics, but a man of life. In fact, life springs from everything he does. He was the first to take me to a disco and to Freddy’s bar and the first to introduce me to a woman. He was my gateway to a circle of friends. Through him, I met Fateh al-Mudarress, Saadallah Wannous, Nadia Khoudour, Mostafa al-Hallaj, Sakher Farzat, Aisha Arnaout, Nazih Abou Afsh, Ahmed Dahbour, Toufic al-Assadi and Nabil Hafar. Through him, I encountered Damascus, when I was 17, a scared, confused man with so much longing. He took me to its streets, quarters, libraries, cafes and bars. Most importantly, he showed me how to catch the spirit of things–words, cafes, paintings, coffee cups, newspapers and even the nightstand where you place your book after finishing your reading at night, before turning in.

From my sister Maha, I learned to read for pleasure. Maha would buy the novels of Colette Khoury and Ghada al-Samman and delve into their world of magic, pleasure and indulgence. From her, I learned that a novel that does not hook me from the first pages is not worth reading.

I come from a liberal family that opened my eyes to a world of endless horizons.

When I was reading the accounts of several political prisoners, including yourself, and through my friendships with some of them, I noticed how your generation transformed long years of imprisonment into a school and cultural lab. What was this experience like for you? How did you innovate tools and educational or theatrical material?

The biggest concern in prison is how to spend the hours of the day. After a while, all memories, stories and jokes run out, and silence prevails among inmates. We had to find a way around this. Theater was the first thing that came to mind.

The idea emerged at the military investigation branch, when I told my friends about the plays I had seen, participated in or wrote about. We thought about presenting a theatrical act in our cells. The idea seemed crazy. Putting together a play without a script, design, makeup, stage or even rehearsal space was insane. But the idea lingered.

We dedicated a small corner of the cell to this purpose, and we covered it with a blanket. I then recalled a script by my friend and teacher Farhan Bolbol, entitled Actors Throwing Stones at Each Other. It goes without saying that we did not have the script to rehearse (we were in a world without books). I reformulated the text in my memory. We distributed the roles, memorized the dialogue and ran the rehearsals. A few weeks later, it was showtime!

This will sound meaningless if I don’t describe our cell to you. The room was eight meters long and three meters wide. The bathroom covered a space of four square meters of that room. We were left with 20 square meters, in which 40 prisoners were crammed. Out of that remaining space, we dedicated three or four meters for rehearsals and shows.

When it was time to act out the play, we felt the same stage fright that actors and directors feel just before the curtain is lifted, when they stand before the critical and staring eyes of spectators. It was time. We had just finished dinner, which was often poached potatoes seasoned with some pepper and oil we would have bought ourselves. We removed the blanket-turned-curtain, and the show started. I feel amazed now when I remember the beautiful performance of several actors, who had never participated in a play or even seen one. The mise-en-scène featured plastic barrels, blankets and empty halaweh tins. We used sheets and other pieces of cloth that we had received during visits. We had to stop the show each time a warden approached the window of our cell. The audience greeted us with real applause. I watched the faces of some of the spectators who had sarcastic grins, and I noticed how they disappeared and turned into smiles then genuine interest and immersion.

In Palmyra and Saydnaya prisons, the experience improved in the presence of real artists who supplemented our own modest attempts. Badr Zakariya was an agricultural engineer, but he had a high artistic spirit and experience from his work at the university theater. I worked with him on turning Sonallah Ibrahim’s novel The Committee into a play. Then, Ghassan al-Jabaei elevated the experience with his academic skills and rich culture.

Along with our theatrical performances, we had our poetry and storytelling nights, our political seminars and even our own press. While in prison, I wrote my story collection Death in the Evening and my novel What Iman Said. Undiscovered poets were also born in prison: Muhammad Issa and Mansour Mansour, to name two.

You and many people of your generation, especially your colleagues in the Labor Communist Party, started out as members of political parties that sought to expand the space of political work in Syria. But now you have ended up outside these parties and direct political work. Why is that? How can we rebuild the politics that the dictatorship in Syria destroyed, if its initial advocates have abandoned it? I am saying this because I have realized that, a decade into the revolution, there is no political party or body that can cause any significant change to Syria’s current reality or give hope that progress might take off in Syria one day.

Perhaps the era of parties in its old notion of grassroots organizations, middle management, leaderships, monthly subscriptions and newspapers has ended. We must find alternative frameworks; new kinds of parties that are more open and do not deal with the infamous “democratic centralization.” Do you know how you become a member of an American party? You just have to say, “I am democratic,” and you’re all set. Nobody has the power to dismiss or forbid you.

I do not mean the experience in Syria should be repeated, but new political frameworks that are flexible, fluid and responsive to rapid developments and that have experience in modern technologies must be sought.

But let me tell you something. The spirit of struggle does not stop. There is no longer a Labor Communist Party, but the Labor Communist Party idea is still there, and one can see it across all components of the Syrian opposition. Some are part of the Syrian National Coalition, others are in the National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change, while another group formed the Citizenship Movement. Some established the Nawat Group, while others, unfortunately, took a closer approach to the regime out of personal or sectarian fears.

What I mean to say is that political culture is more important than political organization. Political culture enriches political organizations, while organization stifles culture.

Testimonies about Wael Sawah

It is difficult to summarize my friendship with Wael Sawah, or maybe I just do not want to now. I still have a lot to say, and I haven’t started writing my farewell letters to my friends. But this chance will not come again–the chance to say that politics ruined my friend’s life and that he paid a very high price for his political work.

Throughout our decades of friendship, and during every step that Wael took, I wondered to myself about the use of all of it. Didn’t the passion for writing grip him enough to make him return to the position he was born for–as a novelist and author of stories rather than journalist?

Wael is still close, although we do not meet often, correspond or speak. But, there is an invisible, yet understood thread between us, which only we can see. Every morning, I sip my coffee with him, albeit through that invisible thread, and with all my close colleagues who are scattered across the globe. Every morning, I tell him many secrets he must know. I am afraid life might pass us by, and these forlorn details might remain buried in a cold place.

Wael is one of those few people I could meet a year, a month or five years later, but we can always pick up where we left off. We laugh and try to reassure ourselves that our small dreams are still intact. He is the best at taking care of the details of his friends’ lives and their souls, including my own.

I think I am partly responsible for not being harsh enough with him to leave politics and return to his natural place. I imagine myself chiding him while raising my scolding finger in his face and telling him, “Son, we are merely novelists and narrators. We carry our imagination in our pockets filled with raisins, dried figs and stories, wherever we go, and this is how we reshape the world.”

Ever since Why did Youssef Al-Najjar Die?—his first collection of stories—up until his novel What Iman Said, I have been waiting in hope. I was not satisfied with the little glimpses that appeared through his articles, especially those he began to write three years ago about his life, the life of Homs and his friends in Damascus in the 1970s. I would tell myself that these glimpses did not quench my thirst for his novels that are yet to be written.

I read what he has written, and I think that his expressions have not lost their grace, which is a good sign. But it is not enough for me. I have realized that I still consider him my little friend whom I should have taken care of and not left to decide his fate on his own.

I can no longer remember when we first met, but I am certain that our first real encounter dates back a long time. It could have been in another life. I enjoy reading Wael’s personal narratives and comments on Syrian political paths with some details I did not know. He tackled these using the style of a short story, whereby the reader can enjoy, learn and contemplate. We met during some endeavors, considered bold at the time, like the conference about Syrian women’s rights. We later established a scientific cooperation relationship that culminated in a co-authored book about civil society in Syria, although it did not get the wide attention it deserved. The current geographical distance between us will not erase the hours of conversation and contemplation we had in Damascus, Istanbul and Paris.

At first, I interpreted his calm and caution as hesitation. I did not know him that well. With time and after our successive meetings and conversations, he taught me that calm does not indicate hesitation. It is rather the mental space to analyze an idea instead of simply rambling.

Wael wrote about politics, civil society and international relations. But he also has personal writings and narratives that are no less important. However, these only stuck in the minds of his appreciators and were only fleeting passages in the memories of his readers.

His bitter years of incarceration were not part of our conversations. But I could read between the lines, or even beyond them, in several of his articles.

Wael was all about direct conversations reflecting caution and modesty, as opposed to a pen drafting unparalleled boldness and honesty.

You encounter some people in life whose seat is always reserved in a gathering, even though they might not be around. Wael was one of those people. It felt like there was an empty seat always waiting for him to fill it—in parties, gatherings and meetings, in love and in life.

Our family was complete—my older brother Firas, Maha, Bashar (siblings, friends, enemies) and I. But our family was waiting for the younger brother who would complete us and complement our joy and fill our big house later on in Homs, after my sister got married and Firas left early on to Damascus, followed by myself and Bashar leaving to study.

Firas brought back many important friends through his relocation to Damascus, including writers and artists. He also brought the bustling life of the 1970s. But Damascus was also waiting for the arrival of Wael, my younger brother, his political thoughts and vision of life and love.

The League for Communist Action, which later turned into the Labor Communist Party, was also waiting for him. He had a spot reserved for him, and he quickly claimed it. The love stories he lived from Damascus to Beirut also awaited.

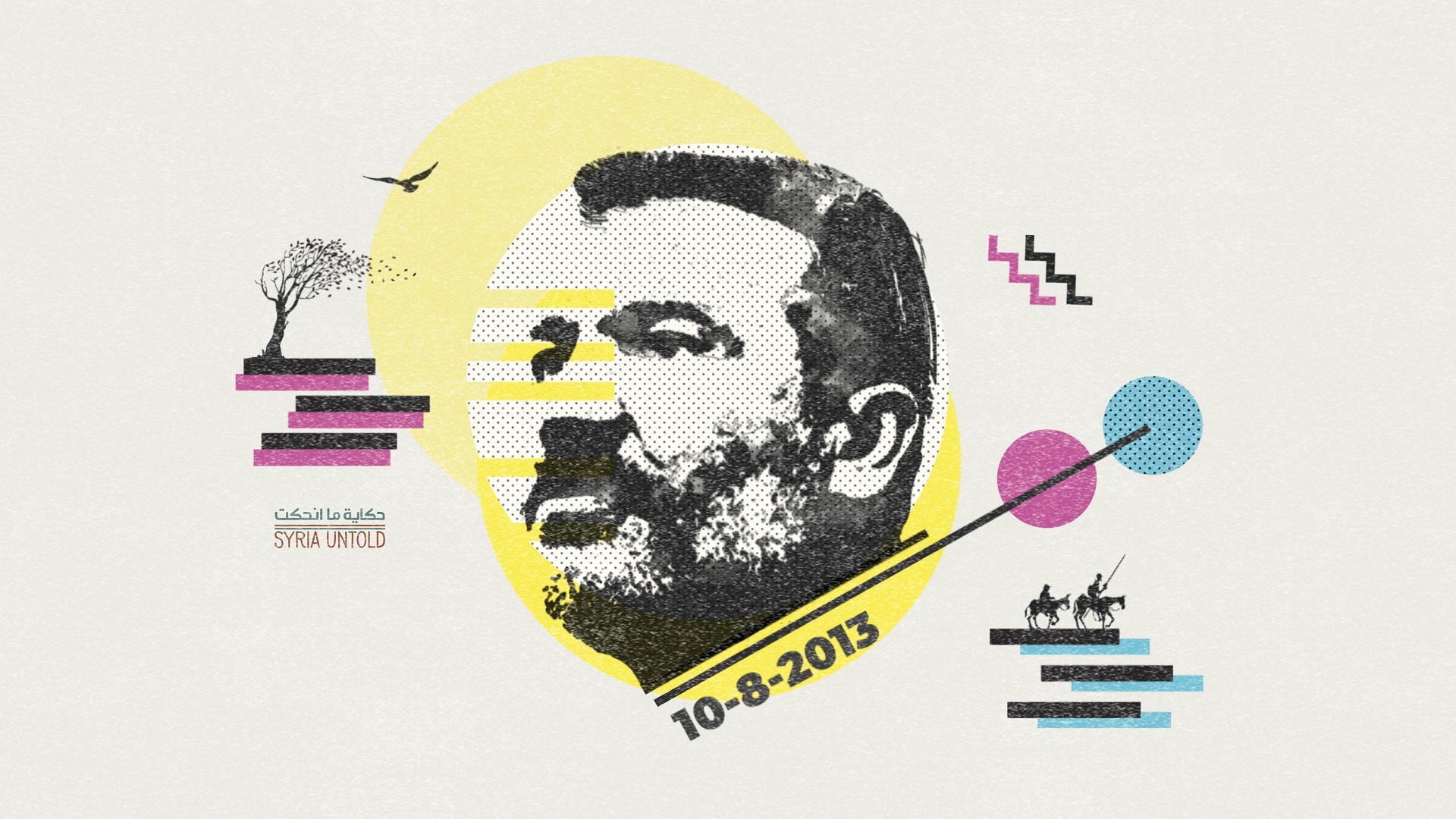

With its hustle and bustle, his stay in Damascus was short lived. Assad’s intelligence service rose against him, and he spent 10 years in its prisons. During these years, his seat remained empty. We awaited his release. His absence was tough, not just for us as a family, but also for his friends and those who loved him, and they were many.

When he was released from jail, the newspaper Alef Today, which I worked hard to establish, also awaited him to be part of the editorial team and enrich it with his culture, courtesy and vision. Wael soon returned to life, politics, writing and madness. Wherever he is, he provokes a sentiment that he has been preparing for that moment for a long time. Today, we are separated by estrangement and a pandemic sweeping through the world. But Wael’s place remains reserved in the hearts of everyone who knows him and in my heart—Wael in San Diego in the US, and I on the other side of the ocean, in Bordeaux, France.

When I look at the path of my friend Wael Sawah, I am lured in by the evident diversity in his experience. When he started out, in the middle of the 1970s, he was among a group of youths who wanted to establish their own path in writing and publication. In addition to Wael, they included Jamil Hatmal, Faraj Birqdar, Fadia Lazkani and Riad al-Saleh al-Hussein, among others. They published some of their work in papers similar to secret publications, which made them intriguing, on the one hand, and the subject of security pursuits, on the other. Under their wing, Wael released two short story collections and a novel before later deciding to quit.

As the experience faltered, proved impossible to continue and escalated, some of its creators, including Wael and Jamil, still managed to cross over to a more controversial and challenging stage, namely the Marxist circles that resulted in the League for Communist Action that later became the Labor Communist Party. Wael spent around four years there, before being detained for 10 years. After that, he criticized the experience, even though he is nostalgic for some of its aspects, just like some of his friends.

He was confused for years, as he was torn between his political and cultural interests. He then took on a controversial job, which required him to compare the pros and cons of culture and politics. The balance tipped in favor of politics, as he accepted a job at the Canadian Embassy, and later at the US Embassy, both in Damascus. He was an advisor in both instances for around a decade. This ended with the outbreak of the Syrian revolution against the Assad regime in spring 2011.

It seems to me that his three experiences and the subsequent acquaintances, expertise and conclusions he made and reached, pushed him to a track where he played an indirect political role in most aspects but drew closer to an almost direct role in some instances, especially in his writings. At the beginning, he played an indirect role in managing the activities of associations that were in close contact with the revolution, including The Day After. He then founded a Syrian organization in the US to track the perpetrators of crimes in Syria. He delved into journalistic writing and diversified his writings between culture, memory and politics, while focusing most on the latter.

A sort of legend shapes the features of political prisoners, from our knowledge of the injustices they face to the rightfulness of their causes. Their image is enhanced with the stories of leftist political struggle around the world, which carries the pictures of all the activists we know. This image is connected to stories, literature and the art of that era and is enriched by the accounts in detention centers. How does a prisoner live? How does he make rosaries and statuettes from bread dough? How does he learn new languages? How do prisoners exchange their few books and magazines? How do they write their diaries on scraps of paper and send letters that traverse prison walls with great difficulty?

My uncle Wael was one of these prisoners. I was almost one year old when he was arrested. His 10-year detention accompanied my years growing up, and I heard the stories told about him—his culture, courtesy, laugh and love stories. His pictures were all over my grandfather’s house in Homs. I grew up watching his brothers come from Homs and Hama on their few, sporadic visits. The feelings of joy and sadness that accompanied these visits enhanced his image in my imagination as a child, and he became a hero in my eyes.

According to a famous saying, “You should never meet your heroes.” Perhaps there is some truth to that. As soon as the prisoners are released, the image that people had painted about their heroes begins to wither gradually, when the hero becomes a regular person in the flesh in daily life. I have seen many heroes fall, but Wael managed to remain true to the image that was chiseled in my imagination. Perhaps my being a child at the time helped in that regard. Perhaps the perfume he started to wear when he was released also left a trail, as did the publication of his novel What Iman Said. Maybe it is because I saw how he rebuilt his life, calmly and surely, and perhaps because he became more of a friend than an uncle.

Today, I return to the image of my hero—that image I shaped when I was just a child. I read what he wrote about his former political work and his incarceration on social media and websites, and I always see in him the image of the hero I had painted in my mind.