Read this piece in its original Arabic here.

“Bulgur is a loyal friend of chickpeas, and he also loves lentils. Together, they make the popular dish called mujaddara, which is mentioned in historic Arab cookbooks, albeit with lentils and rice. It is the custom to sprinkle the dish with a hefty portion of onions fried in olive oil, and to eat it with pickled turnips or a salad of laban and cucumbers.”

-From the book Ziryab’s Kitchen by Syrian writer and researcher Farouk Mardam-Bey.

Mujaddara is a dish of the Levant, cooked by Levantine people and known widely among them. Some people call it “mudardara” when they prepare it with rice, but its most common name across Syria, Lebanon, Palestine and Jordan is mujaddara. Does mujaddara even need an introduction?

In any case, mujaddara is lentils cooked with rice or bulgur, to which we add fried onions melted in vegetable oil. Sadly, there is no mathematical equation that spells out for us the exact proportion of onions that an adult human needs when eating mujaddara.

Origins

We don’t know where exactly the dish’s name came from. Some say that a woman first cooked rice with lentils, and proclaimed that the dish resembled a fair-complexioned girl with smallpox (“jaddari”), and so that became the name: mujaddara. Others say that the name came from the word al-jaddara (“merit”), because mujaddara is worthy of headlining the menu in any Levantine home. “Mujaddara akal muqaddara,” as the people of Damascus rhyme. “Mujaddara is a fine meal.”

People gather and they tell stories. They drink arak, they pick and press olives, they talk, play around and chat late into the night, then they eat mujaddara before going back home to sleep.

As the story goes, the original mujaddara was lentils cooked with bulgur, as bulgur was the food of the poor. Rice was more expensive. We all know the saying: “Rice is proud, and bulgur hangs its head in shame.” The people of long ago preferred bulgur, and so it came to be said that cooking mujaddara with rice was a sort of heresy. But as with all stories of days long past, I can’t confirm that this is really the case. I’d even go so far as to say that this particular mujaddara origin story is false.

In our current miserable and sad times, though, the price of bulgur has become equal to that of rice, even becoming more expensive in some countries. Despite all of this, there is a noticeable preference for bulgur mujaddara in the countryside, compared to rice in the big cities.

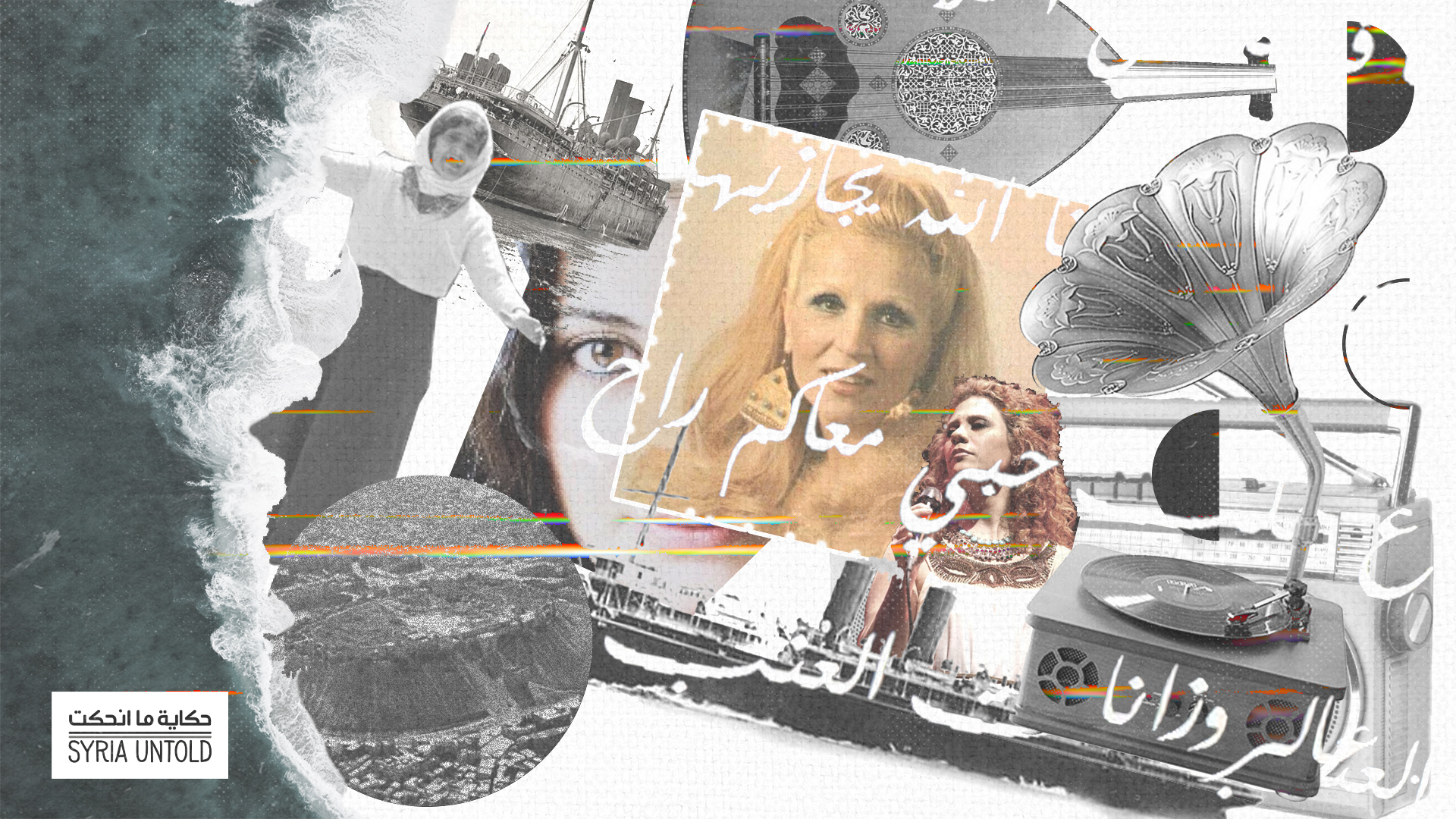

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

Sects

The religion of mujaddara is divided into two sects: that of lentils with rice, and that of lentils with bulgur. In either case, the dish is delicious and melts in your mouth, especially when you eat it with a side of laban or tomatoes—known as bandura by the people of the Levant and tamatem by everybody else. Sip on a glass of arak, the Levant's alcoholic beverage of choice, and you’re merely adding goodness to goodness.

Like all the world’s religions, the religion of mujaddara is divided against itself. There is a fanatical majority that loves eating the dish with bulgur, and a minority of rice-lovers who face disdain and insults for their beliefs. Forgive me if I’m wrong, but if mujaddara was the cause of a civil war, the bulgur sect would be the participants of this conflict, as well as the catalysts and the extremists who neither accept others nor open themselves to new ideas. They’d refuse to develop, and they’d cling to the artifacts of the past.

Not to exaggerate, but I almost equate the extremist mujaddara-with-bulgur-lovers (please note that I didn’t say all lovers of bulgur mujaddara; I’m someone who doesn’t like to generalize) with those who vote for fascist far-right parties in European elections (I’d like to have written “fascist far-right parties in Syria,” but we don’t have actual elections in Syria, nor do we have voting or really anything else resembling a choice).

But in any case, there’s the saying: “It’s my brother and me against my cousin, and my cousin and me against the stranger.” Mujaddara—whether of the bulgur or the rice variety—is the religion and anything else is just sectarianism. (It’s still better with rice, though).

From Damascus’ al-Rawda cafe to Berlin’s Einstein cafe, a heartbeat

28 August 2020

‘Recreating a beautiful thing’

27 August 2021

A fictional narrative, but that’s not such a bad thing

Wrestlers eat mujaddara to become stronger; that’s how it’s been since ancient times. Thousands of years have passed and they still follow the dictates of their holy god of food and abundance, Mujaddarus. And so they partake of mujaddara, which gives them trust in their own strength regardless of their actual physical condition. To the ancients, there was no victory without mujaddara.

Mujaddara long ago became an icon of this region, of the Levant, with all its civilizations, kingdoms, caliphs and princes. People gather and they tell stories. They drink arak, they pick and press olives, they talk, play around and chat late into the night, then they eat mujaddara before going back home to sleep. These have been our traditions since the era of Hammurabi.

Doctors advise people to eat mujaddara regularly for their health. Meanwhile, there’s probably some European anthropologists who proclaim, perhaps out of racism, that mujaddara is the origin of all civil wars that rage in the Middle East. What these Orientalist researchers don’t know about mujaddara (with rice or with bulgur; it doesn’t particularly make a difference here, as the base ingredient is lentils) is that it gives the body renewed energy—that, and the strength of five raging bulls.

They don’t know that mujaddara contains the body’s requirements of protein and calcium, that it helps to strengthen both the teeth and the nerves, that the folk tales speak of it being the cure for almost all diseases, that it contains everything a person needs, that some people eat mujaddara almost every day.

Is mujaddara, or perhaps the energy it gives us, the basis for our countries’ wars, as those Europeans might say? Will these wars come to an end if we stop eating mujaddara? I don’t think so. Walla, walla walla, I swear, we won’t stop eating it even if the sky falls to the earth. Mujaddara is the food of heaven—everybody knows this.