SyriaUntold first published this investigation in Arabic in July 2021, in partnership with the Network of Iraqi Reporters for Investigative Journalism (NIRIJ). Read this report in Arabic here.

More than a year has passed since the announcement of an oil development deal between a little-known American company and governing authorities in northeastern Syria. The months since the deal have seen the Trump administration, which sponsored the agreement, leave office, allowing the new Biden administration to effectively nullify it.

However, mystery still surrounds the terms of last year’s agreement, and many questions remain over the identities of the parties involved.

All that has been leaked to the media since July 2020 has been a statement by Trump’s Secretary of State Mike Pompeo on the existence of a “deal” between an American oil company and the US-backed Self-Administration. The Kurdish-led governing body controls around one third of Syrian territory, centered on the northeastern part of the country. “The deal took a little longer than we had hoped, and we are now in implementation,” Pompeo said in last year’s statement.

Pompeo did not name the parties to the deal, though a report by Al-Monitor in 2020 named the oil company as Delta Crescent Energy LLC, a group formed in the US state of Delaware.

Since then, observers of Syria’s oil file have been asking a number of questions. What is Delta Crescent Energy and who are its owners? How did a small company with no track record in oil development get an exception from the sanctions placed on companies operating in Syria? Who signed the deal and who benefits from it? Does the deal have any political repercussions or is it primarily economic?

Syria’s lucrative detainment market: How Damascus exploits detainees’ families for money

13 April 2021

Conflicting Self-Administration statements

Self-Administration officials have released a number of conflicting statements about the deal with Delta, doing little to clear some of the ambiguity or directly answer any questions. In some cases, officials have understated the importance of the deal, while in other cases they have altogether denied that such a deal exists.

Riyad Dirar, a political leader in northeastern Syria, has released official statements dating back to October 2020 denying the existence of a written agreement, claiming that “discussions are still ongoing within Self-Administration departments about the oil contract.” Dirar is the co-president of the Syrian Democratic Council (SDC), which is the political wing of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), an alliance of US-backed, Kurdish-led militias in the northeast.

The only prominent Self-Administration official who has commented frankly on the agreement is SDF military commander Mazloum Abdi, also known as Mazloum Kobani.

In a media interview in November 2020, Kobane said that “oil is an economic, rather than a political, issue.” He also mentioned Delta Crescent Energy by name, adding that discussions between the Iraqi Kurds and Americans about the terms of the “oil marketing” agreement were in progress and nearing completion.

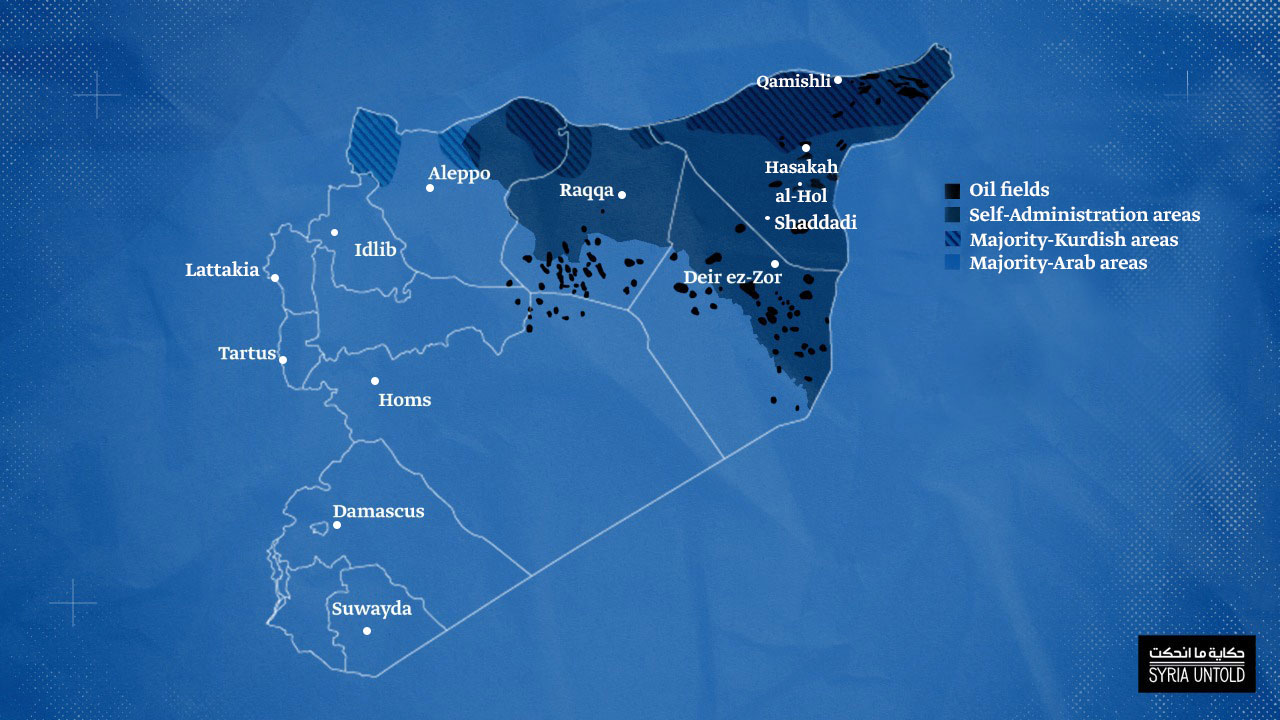

The SDF is composed of a number of armed factions, though its backbone is the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and the Women’s Protection Units (YPJ), groups affiliated with the majority-Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD). The SDF controls vast swathes of Hasakah governorate as well as parts of Raqqa, Deir ez-Zor and Aleppo governorates.

Turkey takes a firm position on the Self-Administration, whose area of control spans along the Syrian-Turkish border. Ankara has called the YPG an extension of the PKK, a group that the Turkish government considers to be a “terrorist” organization and that has been waging a decades-long insurgency within Turkey. Meanwhile, the Syrian regime has described the Self-Administration as a “separatist” organization that is “plundering the country’s riches.” There have previously been channels of communication between the regime and Self-Administration, but they are now halted.

How did a small company with no track record in oil development get an exception from the sanctions placed on companies operating in Syria?

‘Make a deal’

The SDF and US-led coalition forces drove out the Islamic State (IS) from the last vestiges of its former “caliphate” in northeastern Syria in 2019. That same year, then-US president Trump touted the idea of developing local oil. Northeastern Syria is home to the country’s oil fields, which, though largely unimportant on the global market, have historically been a considerable source of income.

“What I intend to do, perhaps, is make a deal with an Exxon Mobil [sic] or one of our great companies to go in there and do it properly,” former president Trump told reporters back in 2019, describing supposedly “massive amounts” of oil in northeastern Syria.

Since then, there have been many questions around how the Trump administration planned to maintain those oil fields in northeastern Syria, in light of the Caesar sanctions that the US enforces on certain companies operating in Syria.

“No major companies are interested in investing in Syria today,” Rami, a source familiar with the discussions that took place in 2019 between Delta and the Self-Administration, told SyriaUntold and NIRIJ. He requested a pseudonym as he was not authorized to speak to the media. Economic sanctions have discouraged large, experienced companies from submitting offers to invest in or develop Syria’s oil fields, Rami added.

In light of the Caesar sanctions, the only way to benefit from oil in areas under the control of the Self-Administration is to obtain a waiver from the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) at the US Department of the Treasury. The waiver exempts certain companies from sanctions.

According to Rami, all of the companies that have expressed interest in the Syrian oil file lack competent experience. But a “total lack of experience” among certain companies, as well as the Trump administration’s apparent political support for Delta Crescent Energy, allowed for the Delaware-registered company to obtain the OFAC waiver, giving it the right to work in northeastern Syria’s oil fields.

But at the same time, Delta Crescent Energy did not represent the US government in any official capacity. Under the terms of the OFAC waiver, the company “is not acting on behalf of the US government.” That is why the past year’s oil deal does not constitute any sort of political obligation on the part of the US to the Self-Administration. Furthermore, the Biden administration earlier this year rejected a renewal of Delta’s OFAC waiver.

Amid the lack of official information, questions remain over the nature of the contract with Delta Crescent Energy. Was it an investment contract for oil fields, or a contract for the protection of wells and maintenance of oil equipment? What were the specific areas covered by the contract? Do these areas have majority-Kurdish residents, or are there also majority-Arab areas under the control of the SDF?

This two-part investigation, produced as part of a collaboration between SyriaUntold and the Network of Iraqi Reporters for Investigative Journalism (NIRIJ) will delve into some of these questions and more.

Mending what has been broken

12 February 2021

‘World War III’ in Qamishli

05 June 2020

What do we know about Delta Crescent Energy?

Delta Crescent Energy has been described in more than one media report as a “mysterious” company. There is little available information on it and its legal status in Delaware, the US state where it is registered.

Last year, the news site Iraq Oil Report revealed the identities of Delta Crescent Energy’s partners, including former US Ambassador to Denmark James P. Cain, retired US Army Delta Force officer James Reese and John B. Dorrier, Jr., former director of the British company Gulfsands, which still has oil exploration, development and production rights in northeastern Syria under a pre-2011 deal with the Syrian government.

Dorrier is not the only one in the group with prior ties to Syria and the region. James Reese has experience in demining operations around Raqqa for the Self-Administration following the battles against IS. He was also Vice President of Blackwater, the American company that carried out the Nisour Square Massacre in Baghdad in 2007. Reese later left Blackwater, founding his own security company, Tigerswan. Trump pardoned those convicted of taking part in the massacre, who were freed in late 2020.

American journalist Zack Kopplin has suggested that there may be additional partners based on the text of Delta Crescent Energy’s OFAC waiver, though most potentially sensitive information on the company has been redacted from the document.

SyriaUntold submitted a number of requests to the US government agencies involved in the agreement to disclose details on the waiver given to Delta Crescent Energy as well as the companies contracted to provide services for it. However, we received a heavily redacted version of the waiver and have yet to receive any remaining documents related to the waiver and details of the agreement.

“What I intend to do, perhaps, is make a deal with an Exxon Mobil [sic] or one of our great companies to go in there and do it properly.” -Former US president Trump

Delta Crescent Energy and Trump

Some analysts have attributed Delta Crescent Energy’s OFAC waiver to political support from the Trump administration, rather than actual professional capabilities.

According to Iraq Oil Report, Dorrier failed to obtain investment rights to produce associated gas in Iraq in 2007, when he was leading Gulfsands, due to the company’s limited professional experience. Iraq Oil Report also revealed a lack of previous recorded activity for Delta in oil investment.

US Deputy Special Envoy for Syria, Joel Rayburn, admitted in a session of Congress in December 2020 that he had met with officials from Delta Crescent Energy and from the Self-Administration, as well as Nechirvan Barzani, President of the Kurdistan Region in Iraq. Barzani is primarily responsible for the Kurdistan Region’s oil file and production and export agreements with Turkey. He also plays a role in intra-Kurdish reconciliation in Syria.

According to official documents obtained by American journalist Matthew Petti, both Cain and Dorrier contributed to financing the electoral campaigns of Republican candidates, including Senator Lindsay Graham, one of the most prominent voices to have confirmed the signing of the deal. Graham is considered a Trump ally and is among those who convinced the former president to keep US troops in Syria even after announcing US withdrawal from the country in late 2019.

SyriaUntold and NIRIJ attempted to reach Delta Crescent Energy and its partners for comment on the matter, but have not yet received a response.

A decade on, how can we work to free Syria’s detainees?

16 April 2021

Syria’s Circassian minority divided, scattered by years of war

27 September 2021

Mediating for an OFAC waiver

Rami, the source with knowledge of the talks between the Self-Administration and Delta Crescent Energy, told SyriaUntold and NIRIJ that Ilham Ahmed, Co-President of the SDC, had met with Delta officials in Washington during a “highly important and unplanned meeting” in October 2019. Reports indicate that other meetings took place between the company and Self-Administration officials previously, in early 2019.

According to Rami, all of Delta Crescent Energy’s known founders—James Reese, John B. Dorrier and James Cain—were present at the meeting with Ilham Ahmed.

Ilham Ahmad confirmed to SyriaUntold and NIRIJ via WhatsApp that she had been present at the meeting. She had been in the US capital at the same time as a 2019 Turkish military invasion on northeastern Syria against the SDF.

Rami added that Delta Crescent Energy officials had asked Ahmed about her discussions with US authorities on the procedures for obtaining an OFAC waiver so that the company could work despite economic sanctions. Prior to this meeting, the company submitted an official request to the US Department of the Treasury for the waiver.

According to Rami, Delta Crescent Energy representatives urged Ahmed to mediate with those responsible for the Syrian file in the State Department—namely, James Jeffrey and Joel Rayburn. He added that the latter played a key role in building their relations with the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and with Turkey, who rejected the agreement, as well as in the OFAC waiver for Delta, granted in April 2020.

Revoking the waiver?

The OFAC waiver clarifies within Page 4, Term 3 that the waiver itself “may be revoked or modified at any time.” This is exactly what happened on May 28, 2021, when the validity of Delta’s waiver expired. The Biden administration did not renew it, possibly because of the ties between the founders of the company and the Republican Party.

The Pentagon confirmed in February 2021, after Biden’s inauguration, that the US Army in Syria “is not authorized to provide assistance to any other private company, including its employees or agents, seeking to develop oil resources in Syria.”

After news reached the media that Delta’s waiver would not be renewed, reports pointed to what could be happening behind the scenes, most notably that the US may have been revoking the waiver to encourage Russia to vote within the UN Security Council for continued entry of humanitarian aid through the Bab al-Hawa and Yaroubiyeh border crossings. A US official denied this scenario to the Al-Monitor news site.

However, the new political climate in the US could present an opportunity for new players to enter the scene, or for old players to enter the northeastern Syria oil race—especially companies that failed to obtain OFAC waivers under Trump.

For the most part, according to media reports there have been four OFAC waiver requests submitted by competing companies in recent years, including that of Delta Crescent Energy. To date, OFAC has not responded to SyriaUntold and NIRIJ’s request for more details on the other waiver applications.

One of those applicants was Israeli-American businessman Moti Kahana, who holds both US and Israeli citizenship. A leaked document showed evidence of an alleged deal between Kahana and the Self-Administration, published in the Lebanese pro-Hezbollah newspaper Al-Akhbar in 2019. The headline of the Al-Akhbar article: “Eastern Syria’s oil in the hands of Israel!”

Kahana, who has business experience in a number of fields, including cars and tourism, showed SyriaUntold and NIRIJ the request he sent to OFAC in February 2019 for his company, GDC, to obtain a waiver to operate in Syria. His application file was registered under the number SY-2019-359047-1. He also shared the responses he purportedly received from OFAC on the matter.

In his apparent request, Kahana proposed that his company export Syrian oil via neighboring Iraqi Kurdistan to the Turkish port of Mersin. From there, he wrote, it could be sent to Israeli refineries then sold cheaply at gas stations in the West Bank and Gaza.

Kahana also showed SyriaUntold and NIRIJ another document related to his OFAC waiver request, though it differs from the request in terms of its stated goals. According to the second document, one of his company’s goals was to invest 25 percent of the oil sales in Israel to buy irrigation equipment and other solar energy-based technology to provide to the Self-Administration. The plan was to request a waiver on the basis of “environmental protection.”

A decade of attacks on Syria’s hospitals, and the medical workers who learned to survive

06 April 2021

Death notices and black market oxygen tanks: COVID-19 in Damascus

10 September 2020

Kahana later told SyriaUntold and NIRIJ in October 2020 that the goal of his plan was to contribute to “establishing peace” between Turkey and the PKK by building an oil pipeline and exporting oil from SDF-controlled oil fields in Syria to Turkey, apparently achieving financial benefits for both sides.

Most of Syria’s oil fields are located in Hasakah and Deir ez-Zor governorates in the northeast and are under SDF control. Kahana’s request to OFAC mentioned the Deir ez-Zor fields, though he claimed to SyriaUntold and NIRIJ that his project would include all the SDF-controlled fields.

However, Kahana’s plans to obtain an OFAC waiver failed, apparently because his discussions with the Self-Administration were leaked to the media before solidifying into an actual agreement. This failure, according to reports, upset Self-Administration leaders.

Kahana’s request also failed for other reasons, according to sources with knowledge of his application, including his lack of experience in the oil trade. He also lacked the political connections to have obtained approval in the Trump era.

Kahana said that he felt that officials under the Trump administration rejected his request due to his membership in the Democratic Party. “They knew that I had donated to the Democratic Party, so Lindsay Graham and James Jeffrey did not answer my emails [related to Syrian oil].”

However, Kahana added in a later conversation with SyriaUntold and NIRIJ, he had not given up hope on obtaining an OFAC waiver under the new Biden administration. In April 2021, he said that he was working on a “major update” to his OFAC waiver application, adding that he was “about to obtain it.”

In addition to Delta Crescent Energy and Kahana’s company GDC, the third OFAC waiver applicant was likely Mashriq Analytics and Consulting, an American firm established on December 13, 2018.

The owners of Mashriq are Luke Calhoun, a retired US military intelligence officer, and Sasha Ghosh-Siminoff, who works in the humanitarian and development fields in Syria.

SyriaUntold and NIRIJ obtained a copy of a leaked “consulting services agreement” between Mashriq (signed by Luke Calhoun) and another consulting firm whose identity cannot be revealed for security reasons. The agreement was signed on January 7, 2019, 25 days after the founding of Mashriq and described a partnership between Mashriq and another company called Sigma Export for mediating the sale of goods and services in Syria, including those related to oil.

It is worth noting that the Sigma Export company mentioned in this document belongs to Hoger Dizayee, an Iraqi-American Kurdish businessman and a relative of Safeen Dizayee, the Kurdistan Region of Iraq’s de facto foreign minister. Hoger is also an investor active in a number of fields, including construction.

According to multiple sources, Moti Kahana was also a partner in this agreement. The purpose of the agreement, Kahana told SyriaUntold and NIRIJ, was to “establish contacts” between Sigma and Mashriq on one side, and the unnamed consultancy firm and the SDF on the other, in order to “invest with them if they obtain an OFAC license.”

Women seek refuge from society in a northeastern Syrian village, no men allowed

07 July 2020

Sultana’s story

10 July 2021

‘Humanitarian’ aims

The plan outlined in the agreement between Mashriq and the unnamed investment firm did not come to fruition for a variety of reasons. Mashriq applied for an OFAC waiver separately in the spring of 2019 but was not granted one, Calhoun confirmed to SyriaUntold and NIRIJ in an interview in April 2021.

In an interview that same month with SyriaUntold and NIRIJ, Mashriq co-owner Siminoff said: “I understood the rough details of what Luke wanted to do, so I told him that if there was anything we could do to help people on the ground [in Syria] then yes, sure, no problem.”

Calhoun explained his motivation for applying for the OFAC waiver, saying that amid US military withdrawal from Syria after Trump’s announcement in late 2019, he worried that “a lot of reconstruction funds would also be withdrawn.” Calhoun saw selling oil as “a backup plan.”

In addition to the companies mentioned above, there is a fourth American company called Sigma3, with Luke Calhoun, Hoger Dizayee and Ahed al-Hindi as its founders. Hindi is a Syrian-American activist sympathetic toward the Self-Administration as well as a former political prisoner under Assad. Sigma3 is a newly established company that describes itself as providing security and logistical services in the Middle East.

According to Kahana, Hindi may have played a role in the Delta agreement due to his connections with the Self-Administration. However, in an interview with SyriaUntold and NIRIJ in November 2020, Hindi denied having any connections with Delta Crescent Energy.

Some sources said that Hoger Dizayee also applied for the OFAC waiver, though his application may have been related to that of Mashriq itself, as the name of Dizayee’s company was mentioned in the agreement that preceded Mashriq’s waiver application by several months.

None of the individuals mentioned above have any experience in the field of oil investment. They claimed in their interviews with SyriaUntold and NIRIJ that they were motivated to enter the business by “humanitarian” aims. Even James Reese from Delta Crescent Energy, the only one of these companies to include figures with some limited oil experience, told the Daily Beast that its intentions were “to help people who need assistance.”

Do we know the terms of the Delta agreement?

There are conflicting reports about the exact content of the agreement between Delta Crescent Energy and the Self-Administration. Riyad Dirar, the SDC co-president, told SyriaUntold and NIRIJ in October 2020 that the terms of the agreement were limited to “maintaining some wells” for potential later investment. This is despite Dirar having previously stated to the media that there was no written agreement at all.

This past January, SyriaUntold and NIRIJ spoke over WhatsApp with Hussein Qassem, an engineer and technical expert now living in the Netherlands. He was responsible for collecting numerical data at oil fields in Deir ez-Zor, Shaddadi and elsewhere from 2008 to 2011. He also worked for the programming division in the Rumeilan Oil Company from 2013-2017.

Qassem published an article on the local Syrian news site Nawat Syria in 2020 questioning the credibility of “some reports on drilling and exploration in a region where the fields of investment, the permeability of the layers, their porosity and their reserves are known to all and do not need to be explored.” Qassem also expressed doubts about the need for digging more wells in a small geographic area where there are already more than 1,600 oil and gas wells.

Delta’s mission is likely to be “handing over refineries, marketing oil and providing oil fields with the necessary supplies,” Qassem told SyriaUntold and NIRIJ, “especially as Damascus still provides some equipment to the fields in the Hasakah Fields Directorate.”

“The Americans want to cut off this relationship,” he added.

According to Qassem, oil from northeastern Syria should be able to meet the needs of the area, feeding the consumption of about 8 million people—that includes residents of Self-Administration areas in the northeast as well as territory under Turkish-backed opposition control elsewhere in northern Syria.

“We’re talking 90,000 barrels of oil per day from the Rumeilan fields alone,” Qassem estimated. Rumeilan is east of Qamishli, a city near the Syrian-Turkish border.

At the same time, residents of northeastern Syria are suffering an ongoing fuel shortage. According to informed sources, most local oil is being sold on the black market to areas held by the Syrian government and the opposition as well as to Iraqi Kurdistan, through traders with ties to the Self-Administration.

Authorities in Self-Administration areas do not publish precise statistics on oil production. Suleiman Khalaf, head of the Self-Administration’s Energy Commission, stated in 2016 that production by the Hasakah Fields Directorate fell from 165,000 barrels per day in 2011 to 15,000 per day in 2016. According to most estimates, oil field production under the SDF, which includes the Deir ez-Zor, Raqqa and Shaddadi oil fields, is about 50,000 to 70,000 barrels per day.

These numbers are smaller than Qassem’s estimate, as black market oil sales make it virtually impossible to determine precise production statistics.

As for the production of the Al-Jabsa Fields Directorate in Shaddadi, a town in southern Hasakah governorate, and the Deir ez-Zor Fields Directorate, which is known for producing a lighter and better quality type of oil, Qassem estimated around a combined 200,000 barrels per day.

Though there are no accurate figures on the national level due to the opacity of Syria’s oil sector, sources indicate that production of Syrian oil fields has fallen since the outbreak of the uprising in 2011, from more than 380,000 barrels per day in 2010 to around 35,000 per day in 2020 as a result of wartime damages. Any oil agreement must include maintenance of equipment, especially the Deir ez-Zor wells, which were damaged during battles against the Islamic State.

As for investment and sale of oil, Qassem believes that opportunities are limited in areas “with a Kurdish majority,” as the fields there are already being fully exploited. Therefore the agreement between Delta and the Self-Administration may include Arab-majority areas, such as the al-Jabsa and Deir ez-Zor fields.

What about Arab areas?

To date, there is still no definite information on whether Arab-majority areas controlled by the Self-Administration were included in the Delta oil agreement. Rami, the informed source, said he agrees with Al-Monitor reporting that oil fields in Deir ez-Zor governorate, which has an Arab majority, were excluded from the deal.

Al-Monitor reported in August 2020 that the geographic area covered by the deal does not include the city of al-Hol south of Hasakah, “in part to head off potential conflict with local tribes.”

A US military source with activities in Syria spoke with SyriaUntold and NIRIJ in March, ruling out the possibility of the agreement covering Arab-majority areas. According to the source, the Rumeilan field near Qamishli, in a majority-Kurdish area, is safer and has better infrastructure than fields in Deir ez-Zor, which happens to have a majority Arab population.

But James Cain, one of Delta’s co-founders, told the Financial Times earlier this year that the agreement covers a larger area than that of the British company Gulfsands, which has been in a contract with the Syrian government since before 2011. If we assume that the area granted to Delta Crescent Energy excludes the al-Jabsa Field south of al-Hol and the Deir ez-Zor field, then its area likely doesn’t differ greatly from that of Gulfsands.

That said, the picture of Delta’s activities in northeastern Syria remains blurry.

Though John Dorrier told the Associated Press earlier this year that Delta’s contracts were estimated at $2 billion, the company took no serious or noticeable steps in its work before the suspension of its waiver, according to numerous Syrian and American testimonies given to SyriaUntold and NIRIJ.

And of course, the Syrian government is not meant to receive any financial gain from the production of the oil wells, or play any official role in this production under the terms of the OFAC waiver granted to Delta.

It is within this relatively restricted context that Gulfsands objected to the deal between Delta and the Self-Administration and insisted on its rights over oil fields covered in the recent agreement. These objections were based on Gulfsands’ prior contracts with Damascus, though the company cannot violate US economic sanctions. However, in March 2021 the Russian company Waterford Finance bought a controlling stake in Gulfsands, granting the latter more flexibility in working around sanctions.

SyriaUntold and NIRIJ have sent a number of requests to Gulfsands to comment on the deal between Delta and the Self-Administration but have yet to receive a response.

Oil refining: A gift from Washington?

Northeastern Syria has historically relied on two oil refineries in the country’s west: the Homs refinery and the Baniyas refinery. Though the northeast has the most prominent oil fields in Syria, it contains no refineries of its own. Some analysts attribute this discrepancy to the Baath Party’s economic and political marginalization of northeastern Syria, where most residents belong to the country’s Kurdish minority.

Since the agreement with Delta Crescent Energy was announced in July 2020, rumors have emerged that it includes the US providing two oil refineries to the Self-Administration through Delta. But in a recent conversation with SyriaUntold and NIRIJ, Riyad Dirar said: “There is no clear answer on this matter, and it is still under discussion.”

Rami, the source familiar with the discussions between Delta and the Self-Administration, said that Washington would indeed give two mid-sized refineries so that authorities in northeastern Syria could distribute oil derivatives to residents at low prices. These refineries would address the problem of oil refining in the region, currently handled by makeshift refineries (harraqat in Arabic) and the environmental and economic damage they cause.

According to Rami, it is not yet clear whether it was the US government (under the Trump administration) or Delta Crescent Energy that promised to provide the two oil refineries. That said, Delta may not have a particular interest in giving oil refineries to the Self-Administration, as the company stands to rake in a much higher profit from exporting crude oil than from selling it already refined.

For his part, Hussein Qassem, the oil engineer and technical expert, believes that the refineries would not refine more than about 30,000 barrels per day to meet the needs of northeastern Syria. He agreed with Rami’s assessment that Delta’s actual goal is to export crude oil to Turkey through Iraqi Kurdistan.

Part one of this investigation dealt with the technical dimensions of the oil agreement in northeastern Syria, as well as how Delta Crescent Energy obtained an OFAC waiver to operate in Syria while other companies failed. Still, many aspects of the agreement remain unknown due to the opacity of Self-Administration authorities, company representatives themselves and US officials.

Follow us in the coming weeks for part two of our deep dive into Delta Crescent Energy, in English.

Bahzad Hammo contributed to the early stages of this investigation.