I was admittedly a bit late to reading Alligator and Other Stories, a collection by Dima Alzayat that came out in the first half of 2020, just as the pandemic was setting in.

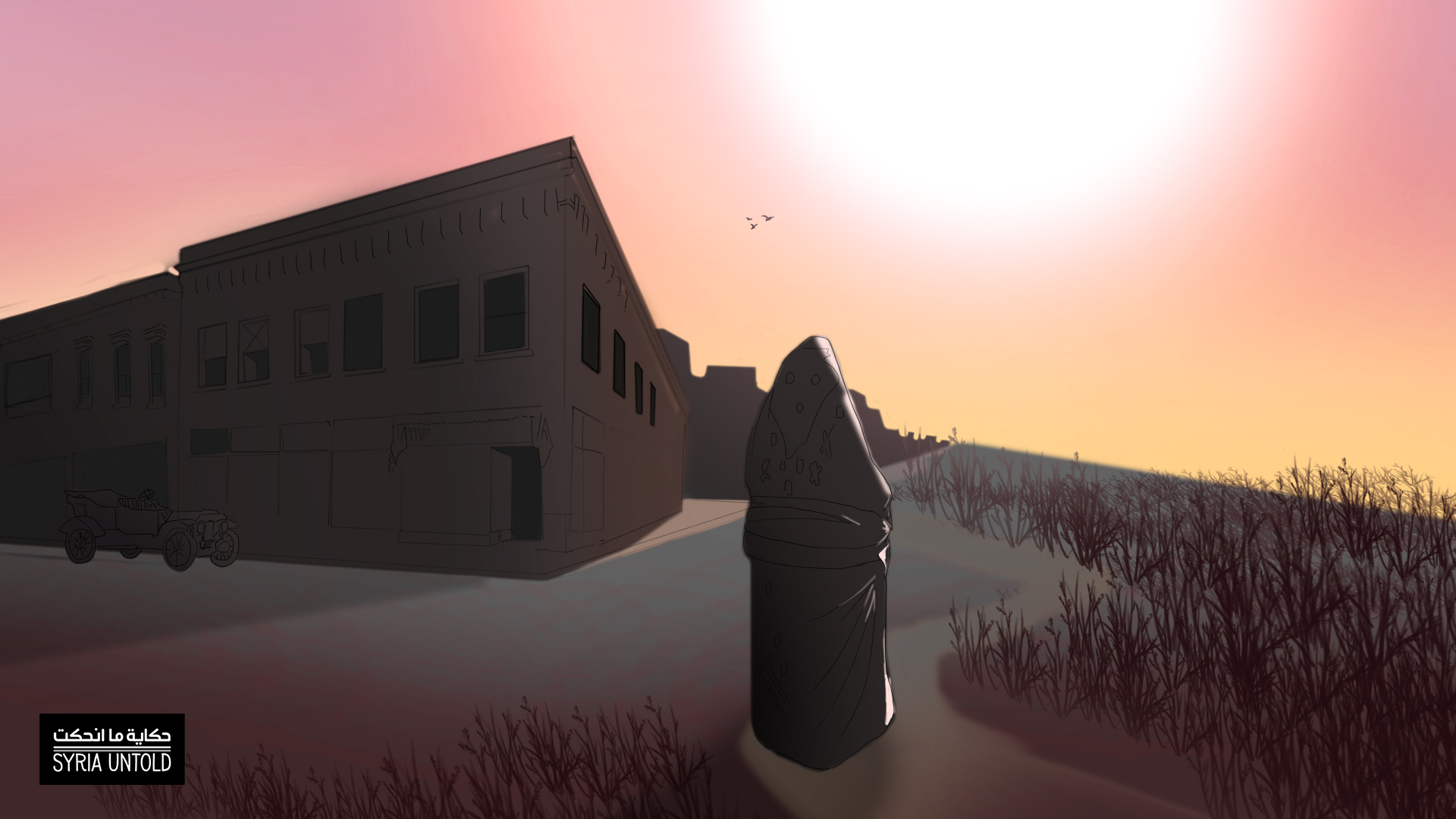

I first encountered Alligator in late January 2022 after finding a copy that had made its way to a bookstore here in Beirut. After two years of living through on-and-off lockdowns, economic collapse, and, of course, the port explosion and its aftermath, the sense of loneliness and unsettled-ness that I found woven through Alzayat’s story collection seemed to strike some chord. A sister lovingly washes her dead brother’s body for burial. Three young boys struggle to keep themselves entertained one 1970s New York City summer, while an infamous kidnapper remains on the loose outside their apartment building. The fragmented members of one family and their surrounding society grapple with the lynching of a Syrian-American couple in 1920s Florida. An elderly Syrian woman now exiled by the war lectures her grand-niece on the meaning of being Syrian—only to excavate a deeply buried trauma along the way. Characters hide their true selves, pass between blurred identities and seem to not quite fit in with their surroundings. Roots, though they exist, feel at times distant or as only faint slivers of what, perhaps, they once were.

“One of the things I’m trying to do in the collection is show all the different ways there are to be Arab or Arab American,” Dima told me over Zoom, from her home in Los Angeles. Though she was born and spent her early childhood in Damascus, Dima grew up in San Jose, California, later working in the film industry and then journalism. “I left Damascus when I was seven, and the memories I have are sense-driven because I was so young.” She remembers birthday cakes peddled by a local baker, making cardboard crafts, neighbors visiting one another in a small street.

‘Recreating a beautiful thing’

27 August 2021

Returning to Abu Alaa al-Maari in our year of plague

13 May 2021

Little material details like these lie scattered throughout the stories in Dima’s collection, often as among the few markers of her characters’ complex personal backgrounds: a Fairouz record, a Qur’an, a school essay. Then there are the bits and experiences that remain intangible: one young woman’s choice not to reveal details about her background as her coworkers share racist views of Arabs, another woman’s decades of silence about her personal trauma, after a life lived mostly within the confines of a police state.

Here, I spoke with Dima about the inspiration for her story collection, as well as her own background story. How has she grappled with notions of American-ness (whatever that means) and Americana, and how do these struggles weave in and out of her writing?

This conversation has been lightly edited for flow.

You were born in Damascus but raised in California. Can you talk a little bit about what your childhood looked, sounded and smelled like before and after you moved to the United States? What are the specific objects and places and emotions that you draw on from this period in your life when you’re writing?

I left Damascus when I was seven, and the memories I have are sense-driven because I was so young. I remember living in a small hara, a small street, where the neighbors were always loud and everyone was talking to each other. We played outside a lot. I remember a lot of fun and laughter. There was a bakery somewhere nearby. Whenever it was someone’s birthday the baker would march up and down the street with the cake they had prepared for the party, and he’d be followed by loads of kids. I remember when it was my birthday, I had this all-white cake with white stars and moons and as the baker carried it, I knew it was for me, and that it was going to my house.

I remember it being really alive in that way, a lot of people going in and out of houses. I think that was the starkest difference when we moved to the States. Everything kind of closed up. Even though my mom’s family lived in northern California, where we lived, it all kind of quieted down.

Arab Americans are seen as a threat, as impossibly American. For many people, perceiving Arab American voices as being representative of Americana would be impossible.

I’m thinking about my own childhood in a suburban area in the US, how intentionally quiet the neighborhood was, how the individual homes were closed off from one another.

Yes. However, the older I get, the more I like having grown up in San Jose. It’s quiet and filled with nuclear families in a way that so many American places are, but it was very diverse. I went to school with a lot of kids whose parents were first-generation immigrants; it wasn’t weird to speak another language or talk to parents who didn’t really speak great English or to bring strange food to school. I didn’t really feel strange for being Syrian.

Your question was also about objects. One thing I remember really strongly from those early years in Syria is the extent to which we had to create our own entertainment. I remember my older brother and sister making us little outfits out of cardboard. We were really competitive about it; I think my dad had come home with some extra cardboard or something, and my brother was really artistic and started making things out of it. I remember wearing cardboard shoes. All of the neighborhood kids gathered around to judge who had made the best shoes. At the time, it was the most fantastic thing I had ever seen, like they were expert artists. When we moved [to the United States], that stopped. It became about playing with things that we had purchased.

The story “Disappearance” is set in 1970s NYC, just after the kidnapping of a young boy. Three boys are confined to their apartment building the whole summer because their mothers are afraid of the kidnapper, who’s still on the loose.

One tiny domestic detail from the story that I really loved was the mother playing Fairouz records at home. It’s a small thing, but it paints the scene in a very physical way for me. I recently read Bye Bye Babylon, a graphic novel by Lamia Ziadé about growing up in the 1970s in Beirut. I was struck by how she uses these tiny details like grocery store logos or drawings of cigarette packs to tell a rich, sense-driven story. How do you choose the small details from your own daily life or observations in order to paint these vivid settings? What material culture are you drawing from?

In “Disappearance,” I imagined that this family had been in the States for a long time, and I wanted a story in which their Arab-ness was not very central. I wanted to show how Arabs are American in ways that aren’t obvious. That story, as we talked about, has to me this tone of Americana; and yet, inserting that this woman is listening to Fairouz, makes the reader realize that this is not, in fact, the white family they might have assumed.

Fairouz or Umm Kulthum or Asmahan—all of these other larger-than-life singers, to me, were such a defining sound in my life. Everybody knew those songs. If a bunch of women got together to dance or sing, these were the singers we listened to. She was listening to Fairouz because who else? It’s that or Umm Kulthum.

I thought a lot, too, about details that didn’t make it into that story. Anytime anyone in my family went to Syria, they came back [to the States] carrying suitcases filled with galabeyas that they would pass out to all the women in the family, and all their female friends. So I imagined the mother in this story having retained these material symbols of being an Arab. The way she dressed, the music she listened to, maybe the food that she made. I imagined her making fasoulieh, or sitting there like I had seen so many of my own relatives sitting there and cutting or snipping the ends of green beans into a strainer before they go wash it. For her, being second or third generation, the only things she still has to convey that she’s Arab are these material things.

You said in a previous interview that the story “Disappearance” had a tone of “Americana” that you had absorbed while growing up in California. How do you define Americana?

While I was trapped in my house growing up, my younger sister and I watched a ton of Nick at Nite. After a certain time in the evening, the channel Nickelodeon would broadcast a lot of classic American shows like The Dick Van Dyke Show and The Mary Tyler Moore Show. We watched them obsessively. Now in hindsight, I understand so much of what was missing from those stories. But to me, there was such an innocence to that entire aesthetic, such a utopian outlook about the US.

As a kid who was trying to understand what the US was and what it meant to be American, these shows were highly intoxicating.

It’s this [narrative of] “Oh aren’t we all having an innocent fun time?” Everything is pure. Everything is possible, and everything is centered on an individual journeying through a thing. That voice, to me, came out of things like The Sandlot, or A Christmas Story or all of those Nick at Nite shows where it’s frozen in quite a nostalgic time in the US, the 50s, 60s, maybe early 70s.

When I was thinking about how to phrase that question, I was thinking, too, about what Americana means exactly. One thing I remember jotting down is celebrating the idea of “America” without questioning the structures in place. Celebrating the idea of police, or “the troops,” or a Fourth of July apple pie, and it’s all quite innocent or naive.

Yes, and these shows were around during the era of Jim Crow, which they never talked about, as if the civil rights movement just doesn’t exist. So they’re highly problematic and not at all truthful. They’re fables of how America sees itself and saw itself at that time.

Yet, as a kid who was trying to understand what the US was and what it meant to be American, these shows were highly intoxicating.

Book preview: Ottoman Syrians at home in the American Midwest

05 October 2021

Do you think this idea of Americana includes Syrian or Arab American stories?

God no! I don’t think it does at all. There is very little room for anyone who isn’t white. And Arab American identity in the States is even more invisible than a lot of marginalized identities. I’m applying to jobs and a posting will say that they’re encouraging diversity and are looking for people from underrepresented backgrounds, but Arab American isn’t a box you can check in the application form.

That identity is complicated even further by the “war on terror” and US aggression in the Middle East. Arab Americans are seen as a threat, as impossibly American. For many people, perceiving Arab American voices as being representative of Americana would be impossible. But that’s exactly the space in which I’m writing. I am very much American, but my Syrian identity is a huge part of how I understand the world and what I write. I don’t think there’s been a place for that identity within what we think of as “Americana.” That is what I’m trying to push back against.

A number of the stories in this collection touched on the idea of Arab Americans “passing”as white. In “Only Those Who Struggle Succeed,” Lina, an ambitious young professional, purposefully “keeps her background to herself.” And the Romys in “Alligator” are sometimes read as a white couple. I’m curious how you think about whiteness when you’re writing these characters.

During the first wave of immigration from Arab countries at the turn of the 20th century, Arabs in the States had to go to court and prove they were white, in order to be allowed citizenship. It laid down this really complex relationship with race. In order for us to belong here, we have to be white, whatever that means. Arab Americans, as you might know, are still designated “white” on the Census.

But I’m not so interested in stories written from a place of defense, that display an urge to show: “Look at how good Arabs are,” or “Arabs are respectable Americans,” or “we’re just like you.” Those stories piss me off. I feel like they are directed towards an audience that disrespects you anyway.

I’m more interested in thinking critically about how Arab Americans can be guilty of the same terrible behavior that oppresses them. In “Alligator,” how was the Romys’ desire for whiteness and acceptance part of a larger structural oppression towards African Americans? And how does that fit into a history of genocide against Native Americans and how we understand race in this country to begin with?

For me, writing is a way to understand my own humanity or my own time here.

How did you first stumble across the story of the Romys? Why was it important to interweave their story with the stories of Black Americans and indigenous peoples in what is now the US state of Florida?

I was doing research for a PhD dissertation about Arab American fiction and race, and I found this case study by Dr. Sarah Gualtieri, who wrote a brilliant book about Arab Americans and whiteness. I couldn’t stop thinking about it.

To me, it was fascinating that this early Syrian-American couple was killed by the police and by a lynch mob. I found it so interesting that they were written about in news reports as white. I also kept thinking about what happened to their children, and what a weird in-between identity they had. Here was this family trying to become white and then their parents are killed for being not white. Where does that leave them, and how do they grow up?

But then I realized that there’s something else at play here. These are such individual stories but their trauma is not individual trauma. This is the trauma of a nation, really. I don’t think that I could completely remove this story from history. How can you talk about racism in the States and not talk about anti-Black racism? How can you talk about anti-Black racism and not talk about the genocide of indigenous people? How can we talk about Florida and not mention who lived in Florida before any of these other people came here? I was peeling back times in history. It was all linked. There’s no way to talk about any of this in isolation.

In three of the stories, we meet characters named Zaynab. First, a sister washing her brother’s body for burial in “Ghusl,” then a seemingly lonely aunt Zaynab in “Daughters of Manāt” and finally a childhood playmate who plays a pivotal role in “Once We Were Syrians.”

You’ve said before that your repeated use of the name Zaynab throughout the collection was accidental, but became a thread that you decided to keep. Have you thought more about what that thread means to you? For me it made me imagine little connections between the different characters’ universes. I kept meeting each of these lost, alienated Zaynabs at different randomized inflection points in their lives.

One of the things I’m trying to do in the collection is show all the different ways there are to be Arab or Arab American. It’s so reductive how Arab women are conceptualized in the US, and I hope that what I write pulls the rug out from under [those narratives]. So this repetition mirrored what I was trying to do: This could be Zaynab, and this could be Zaynab, and this could be Zaynab—this could be an Arab woman, and this could be an Arab woman, and this could be an Arab woman. There is an empathy in this. If she could be the Zaynab from the first story, or the second Zaynab story or the third one, then I could put myself in these different women’s shoes.

There really aren’t so many different stories at the heart of storytelling. We have all these millions of ways to do it, but we keep telling the same stories over and over again. In one of the Zaynab stories, that line or that sentiment actually is stated: “You and I, we are telling only one story.” Even though I meant that within that specific story, “Once We Were Syrians,” I think about that as being true for the entire collection. I’m telling just one story, but from many different angles and directions as I’m trying to think about what it means to be Arab American. What is it like to inhabit that identity?

Your stories evoke a sense of alienation, of not belonging or of in-between-ness. And though you wrote all these stories before covid, I see much of the pandemic reflected in them. A sister prepares her dead brother’s body for burial in “Ghusl,” and then in “Disappearance,” the three boys must stay inside all summer because there’s an unseen killer on the loose outdoors. Have you noticed the pandemic impact your writing or the themes you explore?

I do think that the pandemic has impacted me as a writer. I always need some time to process how I’m feeling about the world before I can sit down and seriously dig. I already know that what’s happening is going to impact what I write next, but I don’t yet understand what that will be. I have really young kids who I can’t let out into the world in the way I’d like. It’s been disheartening to see that the weight of something like this is not equally shared, that there can be so much death and so much suffering, and that so many people just want to go have a drink indoors and get on with their lives.

It’s not like I had the most positive views of humanity before this, but it’s been heartbreaking to see that so many people actually don’t care about each other. It confirms what you already feared.

What can be the role of literature in the middle of all this?

So many times over the past few years I felt like there’s no use—if I sit down and write my little stories, what are they actually doing? Literature can resonate with people and readers can love a story, but I don’t know if that results in any kind of worthwhile action or change. I’m quite cynical about that.

For me, writing is a way to understand my own humanity or my own time here—especially during these past two years, in which I’ve had many existential crises. It’s a place to still be able to ask myself “what is happening?” and “what is the point?” and to explore those big questions. It does make me happy to know if a reader connects with something I’ve written. To me that is the great ability of fiction, and of literature: to make you feel like you’re not alone. To make you understand that other people feel like you do.