This article is part of SyriaUntold’s ongoing series on the world’s “Little Syrias,” communities of Syrians in the diaspora. Read our introduction to the series here.

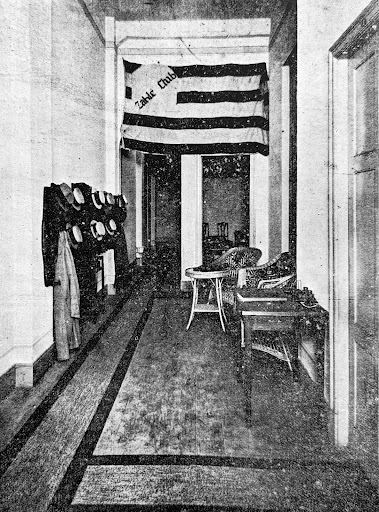

Stepping into the foyer of the Zahlé Club in São Paulo, Brazil, a man could expect to find friendship.

One of a dozen fraternal societies that emerged in the city in the 1920s, the Zahlé Club catered to the colônia síria, the world’s biggest center of Syrian diaspora life at the time. The Ottoman Empire had just crumbled after hundreds of years ruling Syria, and the French Mandate had arisen in its place. Greater Lebanon came into existence, separating from Syria.

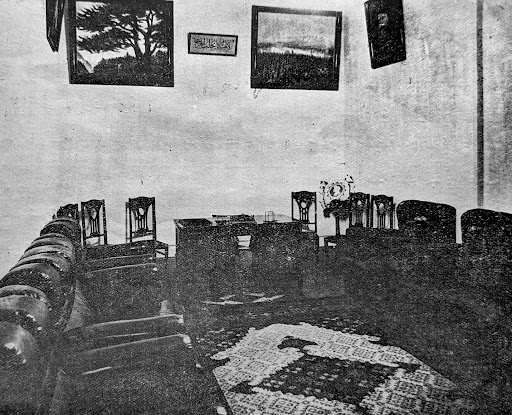

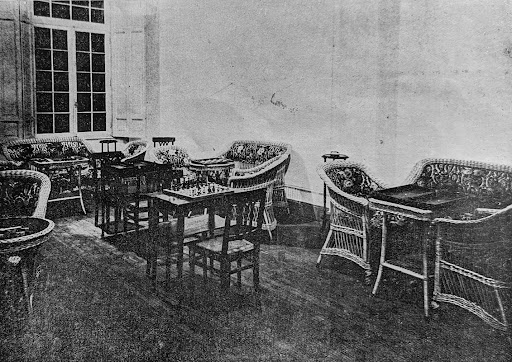

“Division brings demise,” read a sign in the club’s salon, written in Arabic calligraphy. Just beyond it, entrants hung up their coats and stylish straw hats in the latest Paulista, or urban São Paulo, fashion before enjoying backgammon, billiards or poetry over coffee and cigarettes.

More than 10,000 kilometers from Syria, they were in their new home.

The 1890s was a time of massive migration from the eastern Mediterranean. More than half a million people set sail from Ottoman Syria to try their fates in the Americas, known in Arabic as the mahjar. They would work, save money for a few years and, hopefully, return home to buy property. Most of these emigrants arrived first in urban “colonies” attached to Atlantic seaports before fanning out along the railways as peddlers of small textiles, devotional objects or other small wares.

Among those distant lands was Brazil, one of several countries where immigrants from Europe, Asia and the Middle East arrived after the 1890s. In the best-case scenario, the ocean passage from Beirut to Brazil took a month. Finding swift connections among Syrians living in the colony was crucial to a new immigrant’s success. Newcomers from Syria, Mount Lebanon and Palestine identified first with their towns of origin, working within hometown networks as peddlers, storeowners or as port or dockside agents assisting with importing, petty lending and immigration assistance.

“Sírio” soon became an ethnic marker, alongside “libanês,” appearing on the immigration forms used at Brazil’s ports after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. Like other states across the Americas, the Brazilian government drew a distinction between newcomers from today’s Syria, Lebanon and Palestine, and other Ottoman nationals, “turcos,” targeting the latter for exclusion from legal immigration.

From Ottoman Syria to Argentina

02 August 2021

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

By the 1920s and 30s, Brazil was home to the largest community of Syrians outside the Middle East: 162,000 people by the mid-1920s. Their numbers only continued to grow. Many Syrians and Lebanese had an uncle, brother or cousin working in distant São Paulo to send money, Brazilian coffee and books home to their families.

Eighteen-year-old Jorge Germanos was among these newcomers, arriving in 1920 from his hometown Zahle, in present-day Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley. He had planned on going to France to continue his studies, which had been interrupted by the First World War.

For some reason or another, he ended up thousands of kilometers afield in São Paulo, where he found work as a peddler for Zahle-born silk merchants. Germons' family later joined him in 1926, when he had saved enough money.

The neighborhood where they settled, near Rua 25 de Março, was São Paulo’s answer to Washington Street, the main thoroughfare of New York City’s own Little Syria. It was a center of what Germanos would have known as Syrian São Paulo. Arriving Syrians were drawn here for its social clubs, cafés, and Arabic-language print culture. Outside on the streets, small shops abutted tenement housing where new immigrants stayed as they searched for work. Syrian peddlers were a common subject of talk among Brazilians about this street; Brazilian newspaper articles this quarter only solidified the stereotype of peddlers as a hallmark of Rua 25 de Março.

‘Nowhere to go’

Zahle was undergoing turbulent changes when Germanos left home. First, there was the fall of the Ottoman Empire. Then, the rise of the French Mandate.

Though this left Syrians and Lebanese as French colonial subjects in theory, most of them who ended up in Brazil lived within an uncertain nationality category: carriers of defunct Ottoman passports who had not exercised a nationality “option.” The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne granted these emigrants the fundamental right to declare themselves as either Syrian or Lebanese, or to pursue Brazilian citizenship through naturalization. In practice, however, the French Mandate made this process difficult.

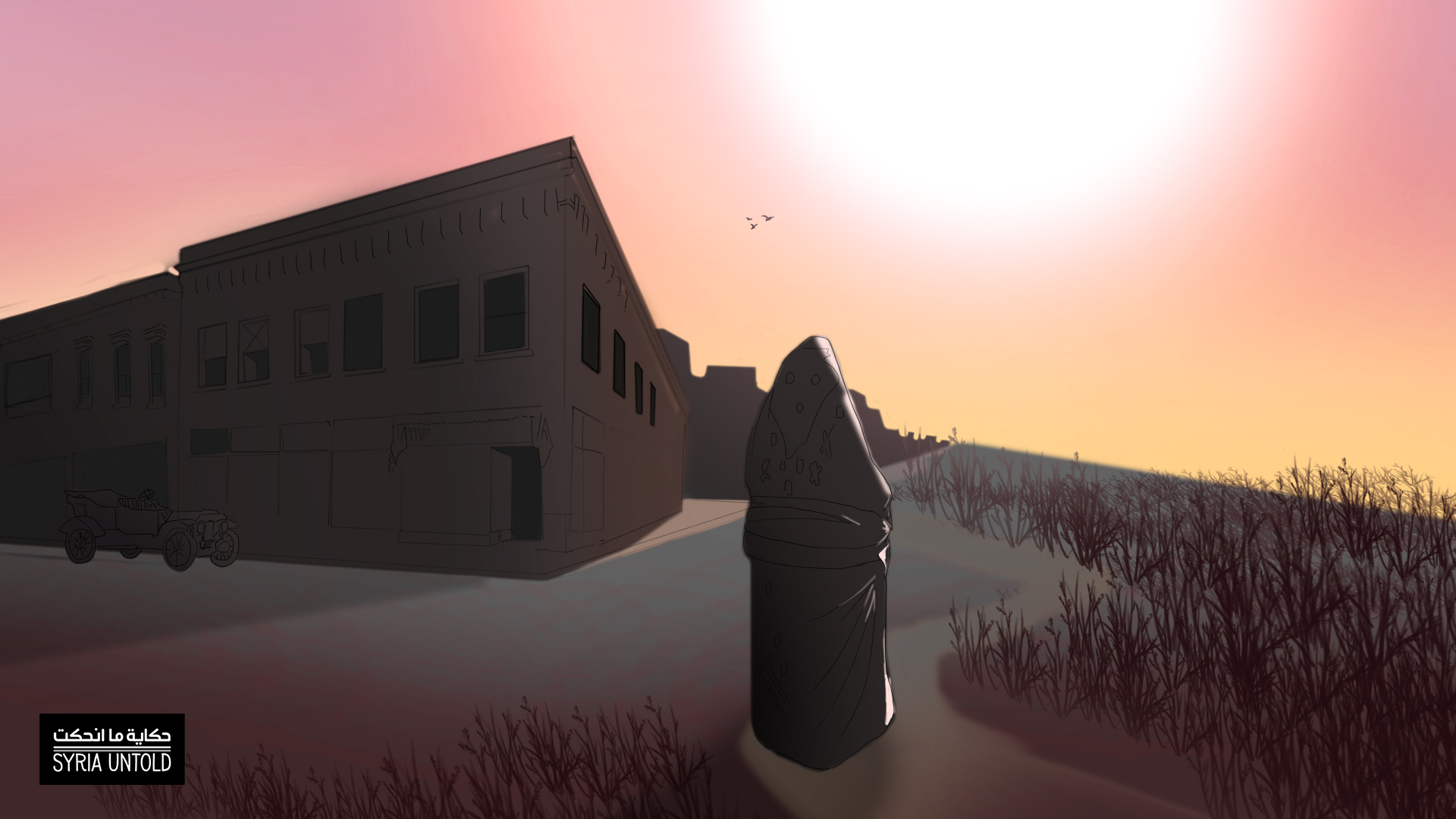

Whether driven by inertia, distrust of the system or outright refusal of French control over Syria, most emigrants simply did nothing, holding onto their Ottoman documents. This presented obstacles when they wanted to travel across international borders or across oceans. They were stuck in the diaspora.

“We are here alone, by God!” Germanos once recalled* telling a friend in 1922. “We have nowhere to go.” That sensation of loss would have been known as ghurba, or estrangement in Arabic; the feeling of exile from home, of alienation.

In addition to being Brazilian, we try to keep the flame of Arabic and Arabism alive.

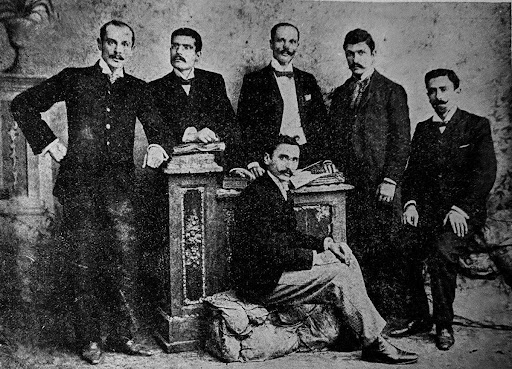

In an oral history interview published decades later, Germanos recounted how he teamed up with fellow Zahalnis, composer Najib Hankash and Jorge Helal, to establish a space for their people in São Paulo. He started by working through hometown networks, campaigning among the city’s textile merchant-manufacturers to raise money. Alongside Hankash, Germanos approached Jorge Bei Maluf, a prominent manufacturer of silk textiles known as “father of the Zahalnis” in São Paulo on account of his father’s Ottoman title. The men wanted Maluf’s sponsorship to establish a meeting hall. He agreed.

Though the Zahlé Club began with men from its eponymous Beqaa Valley town, its members came to include men from both Syria and Greater Lebanon. The club’s exclusively male membership put on salons, poetry readings and plays. Here, an entire fraternal culture flourished, centered on leisure and literature.

And, critically, the club represented a Brazilian extension of the nahda, an intellectual awakening blossoming at the time, closely linked to Syrian print culture in the eastern Mediterranean and emigre networks from across the Middle East.

From newspapers to reading rooms

Beginning in the 1890s, dozens of Syrian-Brazilian newspapers appeared in São Paulo. Most of them were edited by the city’s litterateurs, diplomats, socialists and nationalists: Said Abujamra’s al-Afkar, Chucri al-Curi’s Abu al-Hawl, Jorge Haddad’s O Livre Pensador, Ibrahim Farah’s al-Fara’id, Naum Labaki’s al-Munazir, G Messara’s al-Brazil, Sami Racy’s al-Jaliyya.

These printers thought of their work as bringing the nahda to the mahjar. They published local news, coverage of Syrian affairs in the Levant, Egypt and across the Americas, poetry, political philosophy, novellas and nationalist discourse to mirror those of the urban Middle East. Most of these serials maintained small libraries, reading rooms whose patrons formed the first social clubs in the mahjar.

We would gather 20 intellectuals there in the library and the good conversation would begin.

By the turn of the century, Syrian men could check into the reading rooms. They’d catch up with friends, sip coffee, play tawleh and card games, debate current events. Men could read philosophy or poetry, but just as often they came to learn about job opportunities or simply while away time in the rooms’ leather chairs, amid the dark wood paneling and thick tobacco smoke.

Dozens of these social clubs buzzed in São Paulo’s Syrian quarter by the 1920s, primarily around Rua 25 de Março. Like Germanos’ Zahlé Club, most of them evoked home— named for Homs, Aleppo, Marjayoun, Mount Lebanon or Ramallah—though for the most part were open to any sírio who paid dues and committed himself to its causes.

The men’s clubs excluded women in the name of the era’s ideal paternalistic, respectable Syrian masculinity. Women’s organizations emerged independently; the city’s Hospital Sírio-Libanês, founded in 1921, was the result of a women’s initiative. Women’s groups were also behind the Syrian quarter’s orphanage and boarding school.

‘Keep the flame of Arabism alive’

Walk through the Zahle Club in its heyday, and you’d find room after room for Syrian men to meet, discuss books and plan aid initiatives. A library offered Arabic-language books printed in São Paulo, and likely a half dozen local Arabic newspapers. Nearby, a salon with heavy armchairs was the staging ground for literature and poetry readings, or just arguing politics.

It was here in 1923 that the Zahlé Club put on a play narrating Andalusian traveler Abu Hamid al-Gharnati’s medieval Book of Wonders, dramatizing his exile from Granada as it fell to an Almoravid king, and his exploration of the lands beyond the sea. Jorge Germanos later remembered the play as a tale of displacement and flight. He saw a clear analogy between the story’s Andalusian narrator and Syrian life an ocean away from home, in Latin America. Zahle-born poet Fauze Maluf also performed his poetry here in 1923—it was the first of dozens of diwan readings that coalesced into a new literary movement called the Andalusian League. Writers in this circle represented the southern mahjar’s answer to Khalil Gibran’s Pen League in New York.

Down the hallway, men met for billiards and backgammon; perhaps members met later to play football in an immigrant league with Italian, German and Brazilian footballers, frequently winning tournaments.

Nearby was Club Homs. Just before the club's founding in 1920, Arab rebels fought and lost a last-stand battle against French forces just outside Damascus. The Battle of Maysalun, as it came to be known, killed any hopes for Syrian independence from French rule. The news made its way to Brazil. In the aftermath, club founder Jurj Atlas, a printer from Homs who spent much of his life in various corners of the Americas, envisioned Club Homs as a space to preserve an exiled independence movement. Atlas was a strident Arab nationalist—only four years earlier, Djemal Pasha’s government hanged his friend for his political views.

Jurj died in 1923, but the club carried on, professing a mission to preserve Syrian culture in Brazil. “In addition to being Brazilian, we try to keep the flame of Arabic and Arabism alive,” recalled club member Abrahão Anahuate years later in an oral history interview.

Club Homs was home to a library of Arabic books, serials and newspapers, and nurtured deep ties to Syrian literary production. “Who is an intellectual?” asked member Miguel Kezam as he remembered the salons held there. Born in Homs in 1899, Kezam came to Brazil as a teenager and worked as a salesman. “We would gather 20 intellectuals there in the library and the good conversation would begin,” he said. Participants would consult the library’s stacks of books as needed.

Syrian independence from afar

In Syria and Lebanon, the French Mandate suppressed independence movements through aggressive press censorship, surveillance of activists and brutal military counterinsurgency.

Living abroad and beyond French control, émigré activists had more room to organize. As the mahjar’s largest single colony in the mid-1920s, São Paulo was an epicenter for this kind of activism—much of it within the men’s clubs.

Nabih Salameh was a Homs-born teacher and journalist who came to São Paulo in 1935. Once he arrived, he joined the Liga Patriótica Síria, the Syrian Patriotic League, whose primary goal, Salameh later said, was to “criticize and offend [French] colonialism and demand independence for Syria.”

Nearby, Club Homs welcomed Rev. Hanna Khabbaz, a Syrian minister and nationalist, for a lecture on the importance of national education to combatting French imperialism. His visit was part of a larger tour to raise money for Syrian national schools back home. Arriving in São Paulo in 1922, Khabbaz met an eager assembly of over 1,000 Syrians who came to hear him speak. Like French imperialism, the French model of education would fragment the minds of Syria’s youth, he warned. Not only was Syria in need of a new national pedagogy; it rested on the minds—and the shoulders—of Syrian men in the diaspora to articulate it.

Over time, these spaces transformed to meet the specific charitable and social needs of the community. Mutual aid and fraternal culture were central to life in the diaspora: gathering for a discussion of literature or more formal philanthropic projects, fundraisers, or town halls, institutions like the Zahlé Club refashioned ties of kith and kin as they spanned over oceans.

Becoming ‘Brazilian’

The next decades saw change for São Paulo’s Syrian clubs. Under Getúlio Vargas, President of Brazil from 1930-1945, the country restricted new immigration through racial quotas and ordered the nationalization of key industries. The clubs weren't spared. In 1941, the government ordered the nationalization of ethnic associations, including the closure of many foreign-language printing houses.

“The club became Brazilian” during this period, remembered Club Homs’ Nabih Salameh. By his account, it went on emphasizing ethnic culture while downplaying its transnational links to the Middle East. Many Syrian newspapers began publishing in Portuguese. As a freelancer who wrote in Arabic, Nabih began writing for Syrian newspapers abroad, rather than the local ones.

Even as Syrian print and cultural outlets struggled with the nationalization order, Syrian fraternal societies continued their reconnective work, in some cases until today.

Syrian clubs were never unique to Brazil or any other corner of the mahjar. Zahlé Clubs popped up in Lawrence, Massachusetts; Peoria, Illinois; and in Mexico City. Buenos Aires, New York City, and other parts of Brazil all had their own versions of Club Homs. As sites of reconnection, fraternalism in these clubs blurred the boundaries between “here” and “there.”

And as the Syrian libraries in São Paulo downsized or closed altogether, they went on preserved in personal collections before ending up in estate bequests to libraries elsewhere.

One library belonging to Syrian-Brazilian poet Fauze Maluf ended up thousands of miles away, at the American University of Beirut. Other bits and pieces of this social world would reappear in research collections in Brazil and the Americas—or altogether scattered across continents.

* Author’s note: The oral history interviews excerpted here were published by Betty Loeb Greiber, Lina Saigh Maluf, and Vera Cattini Mattar, Memórias da Imigração: libaneses e sírios em São Paulo (Discurso Editorial, 1998).

Edited by Madeline Edwards