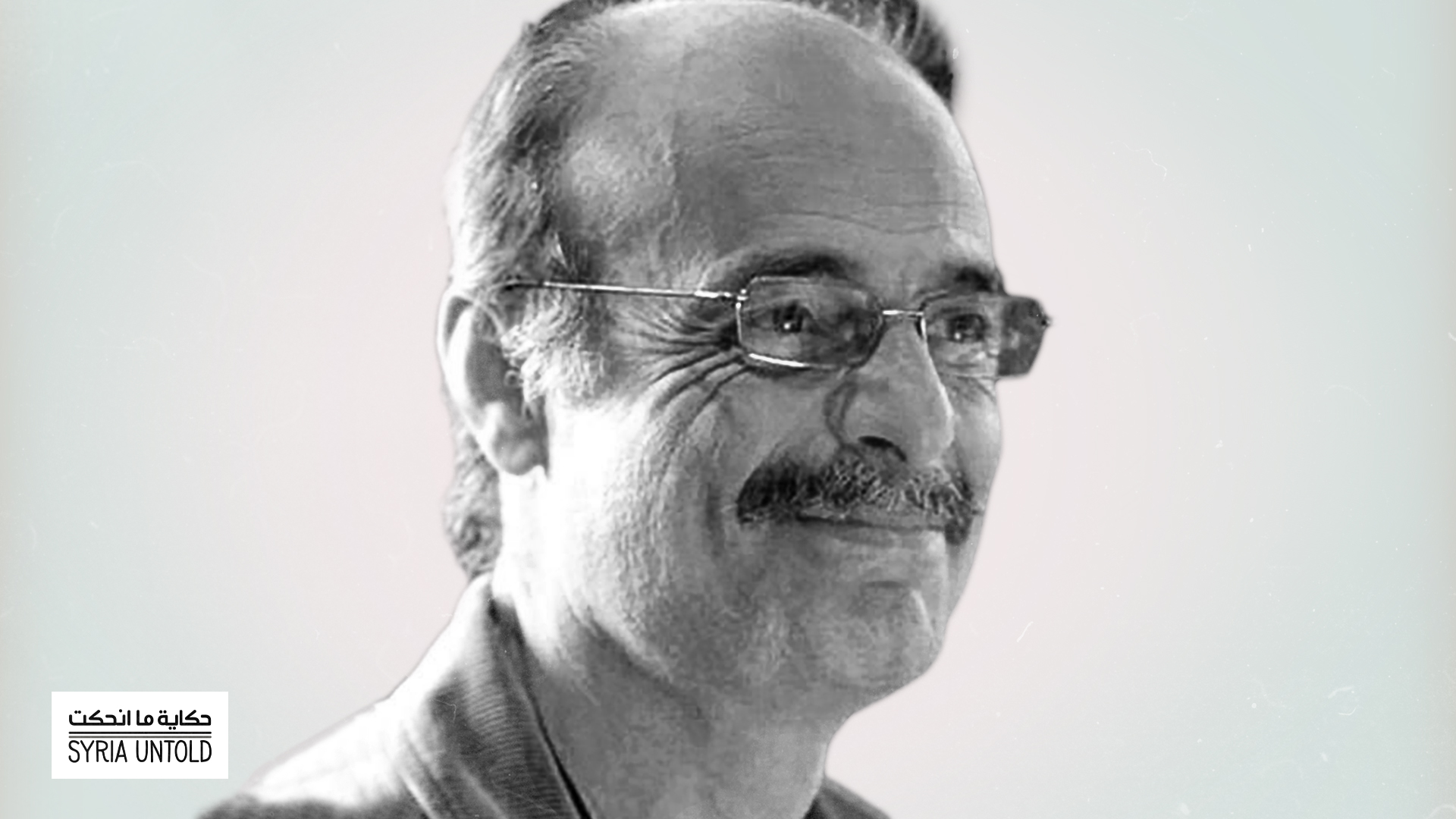

Syrian director and photographer Mohamad Al Roumi was born in Aleppo in 1945 and graduated from the Faculty of Fine Arts at Damascus University in 1972. He began his artistic career as a painter, then turned to photography. Roumi’s photographs came to be featured in books, articles and cultural exhibitions across Syria, North America and Europe. He then shifted his focus to filmmaking, finishing his documentary film Blue-Grey in 2002. The film appeared in dozens of international festivals and was followed by a number of other short films.

Roumi also has decades of academic research experience on the history of Syria through his work alongside European archeological teams that came to his home country from the 1970s through the 1990s. He is considered an expert on the history of Syria’s Jazirah region, as well as the Euphrates River Basin, where he spent much of his childhood.

Fellow Syrian filmmaker Eyas al-Mokdad conducted the following interview with Roumi.

As I mentioned to you before, I’ve done lots of research on Syrian cinema, especially auteur cinema. But I’ve got a bit deeper than that. Political and social life in Syria has seen radical changes that impacted people’s lives and the natural environments in which people live. So I’m interested in speaking with you on two levels: First, to understand you as a Syrian visual artist who has documented historic heritage and the natural environment, and second, as someone who has delved into the devastating impacts of state-run development projects on the Euphrates River. Tell me more about your knowledge of this region of Syria.

What I said at the beginning of Blue-Grey is the truth. I was born in Aleppo, and because of my father’s work, my family and I all moved to Tal Abyad in the Jazirah region of Syria.

What was your father’s job?

He was involved in the trade of grain and seasonal crops like cotton. I stayed in Tal Abyad until I was 14, when my mother pressured us to move back to Aleppo. My memories of the Syrian Jazirah are the ones that stick from childhood, pure memories, as the mind preserves beautiful things. What remains in my mind are those beautiful times I spent in Tal Abyad.

I would go on to study at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Damascus, where I would later live. My return to the Syrian Jazirah after that was under very peculiar circumstances: I had joined the Syrian Communist Party at the age of 18.

Before you delve into that stage of your life, can you tell me about the people and life in the Jazirah region, those beautiful things that remain stuck in your memory?

As a child, my consciousness had not yet fully matured. I was observing and analyzing everything, arriving at the conclusion that the people who lived alongside us in the Syrian Jazirah were living in great harmony with the surrounding environment. I don’t doubt that the people there suffered from a host of problems. They needed financial support, they needed education for their children. Imagine: some of the villagers had built their children’s schools themselves and at their own expense, then went to the Ministry of Education to ask that they be staffed with teachers so that the schools could start running. This was all due to these people’s awareness of the importance of educating their children.

The Jazirah region was neglected at that time for a number of reasons. It had a low population density relative to the rest of Syria, which back then had no more than three million citizens. These people worked in agriculture, usually rainfed, or on “decade” land—that is, land that is fertilized once every 10 years. But they were living in a state of harmony and contentment, and they would have preferred to go on living their lives as they were rather than move to other, more generous places. During periods of scarcity, they would send their children to work in Lebanon.

Tal Abyad is a special city, and it had clearly delineated ethnic neighborhoods. My relatives, or the people who were from my family, all lived in a certain neighborhood. There is a famous clan that lived in another neighborhood. There were Armenians, Turkmen, Assyrians. When we were children in school, or even as teenagers, we didn’t discriminate between the different ethnic and religious groups of the city. The only time we did was during summer vacation, when we’d play a game where we’d throw stones at each other with our Armenian friends from school. We divided ourselves into two groups: the Armenian team and the Arab team.

Within the margins, and breaking free: Syrian cinema

23 January 2021

Hala Abdullah: 'I believe in cinema as a means of resistance’

11 June 2021

The Syrian Jazirah is home to branches of Arab tribes, spread out across the area. When the ground is barren in the dry seasons, people depend on herding and raising livestock. In the fertile seasons, they live as farmers. Agriculture in the Jazirah was rudimentary, not like in the Orontes River Basin, where agriculture was developed and the farmers were able to grow a variety of crops. Farmers in the Jazirah used to sow wheat in the ground and then wait for something good to come of it. One bag of seeds would produce between 20 and 30 bags of wheat, that’s what I understood from the farmers there—this would have been considered a good season. Such was the situation in the Jazirah.

We must also distinguish between two areas: the Syrian Jazirah, and the Euphrates River Basin, the latter of which was clearly more agriculturally developed than the former. In the 1950s, farmers in the Euphrates River Basin were able to obtain water pumps. That was during the period that came to be known as the Cotton Revolution, when the local peasantry became cotton farmers. But their production could not develop further because of the nature of the Euphrates, which is classified as an “aging” river. That means the water changes its course often and creates little temporary islands while making other islands disappear. This has made sustainable farming a very complicated issue. The inhabitants of this region prefer to be in the desert when it is fertile, rather than to stay in the Euphrates basin and continue farming in those conditions.

Tell me about Aleppo when you moved back there at age 14. What did the city look like at that time?

Let me tell you a little story about that. When we returned to Aleppo, we lived in an apartment building and left behind that Arab-style house in Tal Abyad, that “house of the earth” that opened up to the sky. We lived in a neighborhood in Aleppo that played both a positive and negative role in the history of Syria. Abdelrahman al-Kawakbi was from that neighborhood, as was Nathem al-Qudsi, Amin al-Hafez, governor of the Central Bank of Syria Abdelwahhab Hamoud, and Abdelhamid al-Siraj, who established the repressive intelligence services and their torture methods in the 1950s. This neighborhood was known as the one “under the Citadel,” and it had very clear political activity, especially leftist activity.

I was a newcomer, and I didn’t know yet if I was now a city boy, or if I was still a villager. I bought shiny black shoes, and they made me feel happy. I wanted to shine my shoes, so I stood at the shoe-shine box and put my feet on the box for the worker to polish. But there was a young man already there who was a regular customer. He put his feet on the box, in my place. I was young and had a bit of nerve, so I did the same thing right back at him. I pushed his foot and put mine back on the box. That man, who later became my friend, was Sharif Shaker. He’d go on to become a theater director.

There were four or five boys in our friend group, each of us with our own mindsets. This was thanks to Hussein al-Shawi, who worked as a clothes presser in the neighborhood. He took it upon himself to educate us, passing us books by Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Maurice Thorez and many other leftist books after those.

Later on we five friends discovered that we had all joined the Communist Party, each in our own way—also thanks to Hussein the clothes presser. He worked in a little dukkan shop for a while, then decided to leave the shop in our neighborhood “under the Citadel” to me, so that I could run it for him. He told me: “Well, this shop is yours. I’ll go open up another one in my neighborhood, in Bab al-Ahmar.” That’s how I became a clothes presser while also working on my studies. On Thursdays we’d have our regular hangout session together: me, Sharif Shaker, Toufiq al-Muazzen, Hussein al-Abras and Radwan Hilal. Mostly we’d drink and have discussions. To be honest, I owe a lot to this group of friends, who decided to bear the burden of sending me to Damascus, to study at the Faculty of Fine Arts. I applied alongside more than 160 other applicants, and I was among the 16 they accepted.

My friends in Aleppo were state employees with monthly salaries. They agreed that each one of them would contribute 25 liras from their salaries every month to support me during my first year in Damascus. After that I’d be responsible for my remaining years. They are the ones who helped me enter the Faculty of Fine Arts.

Did you paint before enrolling in the Faculty of Fine Arts?

Yes, I started when I was in primary school in Tal Abyad. I saw that the school principal, who came from the Ghourani family, had lots of paints in his office. I’d see him make his white canvases, then go to the bridge in Tal Abyad, which sits between two gardens, and he’d paint the nature there. I stole some of his paints and tried to imitate what the principal was doing. My uncle found out about my crime and informed on me to the principal. The principal’s response was to buy me an art set and teach me how to paint. I stopped painting when we moved to Aleppo, but then started up again during my years of work and study. I was encouraged by many people, including an art professor from the al-Ghrawi family, who also taught and looked out for me.

So at this point in your youth, you had just arrived in Damascus to study at the Faculty of Fine Arts, and you were also a member of the Communist Party.

I was 18 years old at the time, and yes, I had been a member of the Communist Party for a year when I applied for the Faculty of Fine Arts. With the help of my friends, I was able to live and study in Damascus. In my second year there I started teaching a certain number of hours, which I did until I finished my studies.

Who was leading the faculty at the time? What were the brightest names?

There were no more than 80 students at the time in the Faculty of Fine Arts, across all of the disciplines, and we had about 35 teachers. Among them were Fateh al-Mudarres, Muhammad Hamad, Naseer Shoura and a number of other well-known and pioneering professors and artists. Teaching at the faculty was how they made their living.

I feel that art cannot be taught. Instead, the right environment allows for experimentation and artistic thinking, alongside the important guidance we received from our professors. I don’t know if you’ve spoken with any of the other people from my generation who attended the Faculty of Fine Arts and who perhaps told you what our years there were like. What we experienced at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Damascus was similar to other art institutions elsewhere in the world, meaning that we had absolute freedom. That was thanks to the dean of the faculty, Muhammad Hamad.

The faculty’s neighbors called the police on us once because we were lying naked on the roof enjoying the sun. There were many similar incidents. I and other members of my generation did pretty much everything.

But life circumstances often push someone down a path in life that they haven’t really chosen. I remember when I met with my friends in Aleppo when we were 16 years old, and we were telling each other our dreams for the future. I wanted to continue painting, and Sharif wanted to work as a theater director (and that’s what he did). But in the 1970s Hafez al-Assad issued a decree to form the National Progressive Front, and one of the front’s most consequential actions was to ban communists from working in education and in the army. This forced me to search for another source of income after graduation, as I wouldn’t be able to work as a teacher.

Did the authorities know that you were a communist?

Yes, definitely. The party was underground, but it decided to share the names of some members in order to negotiate with the Baathists. Mine was among those names, to represent the communist students. I attended the negotiation sessions with the Baathists, as a representative. At the same time, there were fellow communists dying under torture in regime prisons. Hafez al-Assad’s authorities never abolished the division tasked with persecuting the communists, though they claimed they did. All they did was put some communists in ministerial positions. But their ultimate goal was to eliminate the Communist Party altogether.

Anyway, I started looking for a source of income. At the time, one could work as a painter and technician with foreign archeological missions that had come to Syria. My work with these archeological crews brought me back to the Jazirah region more than 10 or 12 years after I had left. By chance, I returned to the same place from which I had left as a child to Aleppo.

I went to work in Tal al-Mureibet with an archeological expedition led by a man named Jacques Cauvin. He realized through his research that humans discovered agriculture during the period in which they enjoyed self-sufficiency, when there was an abundance of food. This allowed humans to contemplate nature: if they put a grain of good quality wheat in the ground, it would sprout. Before, the prevailing theory had been that humans discovered agriculture because of need rather than because of abundance. As Cauvin discovered, humans achieved agriculture because of their prosperity. The beautiful thing is that when I was a boy waiting to cross the Euphrates River from the Jazirah side to the Shamia side (the side where the river basin ends), we discovered the first house built by humans. It was later submerged by Lake Assad. Cauvin told me: “Muhammad, you will paint the first house, and it will be published in your name.” And so I drew the blueprint of that house and, indeed, it was published under my name.

I’m very meticulous with my work and care a great deal about my reputation, so I started receiving more offers to work with archeological expeditions in Syria. Those included German expeditions. I worked with Eva Strommenger at the Tal al-Habouba site, which dates back to the third and fourth millennia BCE. I collaborated with nearly 50 such expeditions, doing any tasks required of me, whether topography, photography, paintings, etc. This was a way to secure an income for my studies and to support my family.

As for why I left painting and turned to photography, painting requires a bit more stability and long-term experience. I was working with watercolors and pastels, materials that are easy to use. Then I discovered photography when I was asked to photograph a series of archaeological sites and artifacts. It was during this period that I returned to the house in Aleppo and I took a photo of my family. That family photo showed me the expressive power of this new medium, and I realized that photography can be a form of artistic expression.

People know me as an archaeological photographer. This is true, but I’m also a photographer for myself. I also do not see many of the boundaries that supposedly separate photography from cinema.

When did it become necessary for you to begin your relationship with filmmaking? Did you have friends working in the medium at the time?

Cinema has always been necessary, but modern technologies have made working with cinematic art a smoother process. With only an ordinary camera, you can create cinema. While for a feature film you need a huge crew and tons of funding, you can make your own personal film for just a few dozen liras.

Technological developments have created a sort of democratization of art. It has become possible to produce high-quality films at lower costs. The quality of cinema isn’t in the technical aspects of the work, but rather in the idea behind it, to a degree. The expressive power within the material is what imbues the film with value.

You can make a good film with simple means, and a bad film even with great resources. Abbas Kiarostami’s film And Life Goes On is about a car traversing an area in Iran devastated in an earthquake. The main character meets people from the region affected by the earthquake and has conversations with them. The cost to make the film was simply the price of the 16mm film strips. This low-budget film won an award at the Cannes Film Festival. Meanwhile, a film like The Titanic, which cost millions of dollars to make, is nevertheless considered by most people to be frivolous.

I made the film Blue-Grey in 2002 as an invitation for the viewer to learn more about what happened in the Jazirah region. It was also a sort of nostalgia for me. The film is about an area submerged in water. We don’t see any of what has been submerged, though the water has erased an important part of human memory. Tal al-Mureibet, which was the site of the first ever house known to humanity, the first site of agriculture, was submerged beneath the water of the Tabqa Dam. The dam drowned around 160 kilometers of the Euphrates River Basin, which contains some of humankind’s earliest memories. We could have benefited from these areas if not for the dam.

Tell me more about your work as an archeological and environmental researcher in Syria. You have a wealth of knowledge about the history of Syria and its natural environment—how did that knowledge develop? Was it through working with these foreign archeological teams?

Whoever lived in the Jazirah region of Syria like me and witnessed the life that I witnessed would have a deep desire to know everything about it. I’ll tell you about the young man who put together my latest photo exhibition in Cologne. His name is Jabbar Abdullah, and he’s from a tiny village called Thadiyeen on the banks of the Euphrates, at the crossroads of the highways to Raqqa and the historical city of al-Rusafah. There is an archeological site in Thadiyeen where Germans came and worked. Jabbar worked at that site since he was a small child. This is the place that [founder of the Umayyad dynasty] Abd al-Rahman I fled when the Abbasids took over. He and his brother were to flee the city by river, but his brother couldn’t finish swimming across. The brother died, while Abd al-Rahman I continued on to Andalusia in southern Spain.

Anyway, Jabbar came to Germany fleeing the Assad regime’s bombs, which rained down on those people living in the village. He’s young, your age I think. He learned German very quickly, and a few months ago he published his first book in German. Because of his previous work with the archeological expeditions, he started working in the Museum of Islamic Art and is doing very well as a researcher. My own knowledge about Syrian history is like that of Jabbar and others who are from that region and are passionate about research, in addition to having lived in that place, with all its dimensions.

When we were shooting your film To the End of the Earth in 2006, in a village on the banks of the Euphrates, I was working at the time as an assistant director of photography for Miyar al-Roumi, your son and my friend. I spent a few moments contemplating the mud houses in the village and wondered: What is civilization? You’ve visited “civilized” countries in Europe, and you’ve also seen that the residents of these mud homes have their own very old civilization.

This is true. There is a difference, though, between civilization and urbanization. Someone can be well-versed in modern technologies like social media, but at the same time be completely backwards!

There is a kind of accumulation that occurs among people. I cannot say that the residents of those areas have been living in them since those first houses in human history some 12,000 years ago. At the very least, we can suppose that they’ve been there since the discovery of writing in the third millennium BCE.

You feel that they have an accumulation of knowledge. They look into your eyes, they know what you’re looking for, and they respond accordingly. They leave their villages to work in Lebanon, but then they return home to marry and settle down. They prefer to be satisfied with what they have in that environment, rather than to ride around in luxury cars and go on these fake parades.

I believe that the most important thing in a person’s life is the balance they create between themself and the environment in which they live. Ask yourself this question: From the European Renaissance to the 19th century, how many intellectuals, philosophers and poets passed through Europe? Though there were many, they were unable to stop the tragedies and wars that pulverized people and the stones of their cities. What is the value of all this “civilization” if it can not develop a humanity that lives in peace?

What is happening in Syria is a denial of the value of humanity and civilization. Nobody has been able to help the everyday Syrian people in their struggle for freedom. The leaders of those societies that we call “civilized” don’t see past providing basic needs like food and water. The world order continues to treat civilization as a commodity, and it is responsible for conflating true civilization with urbanization.

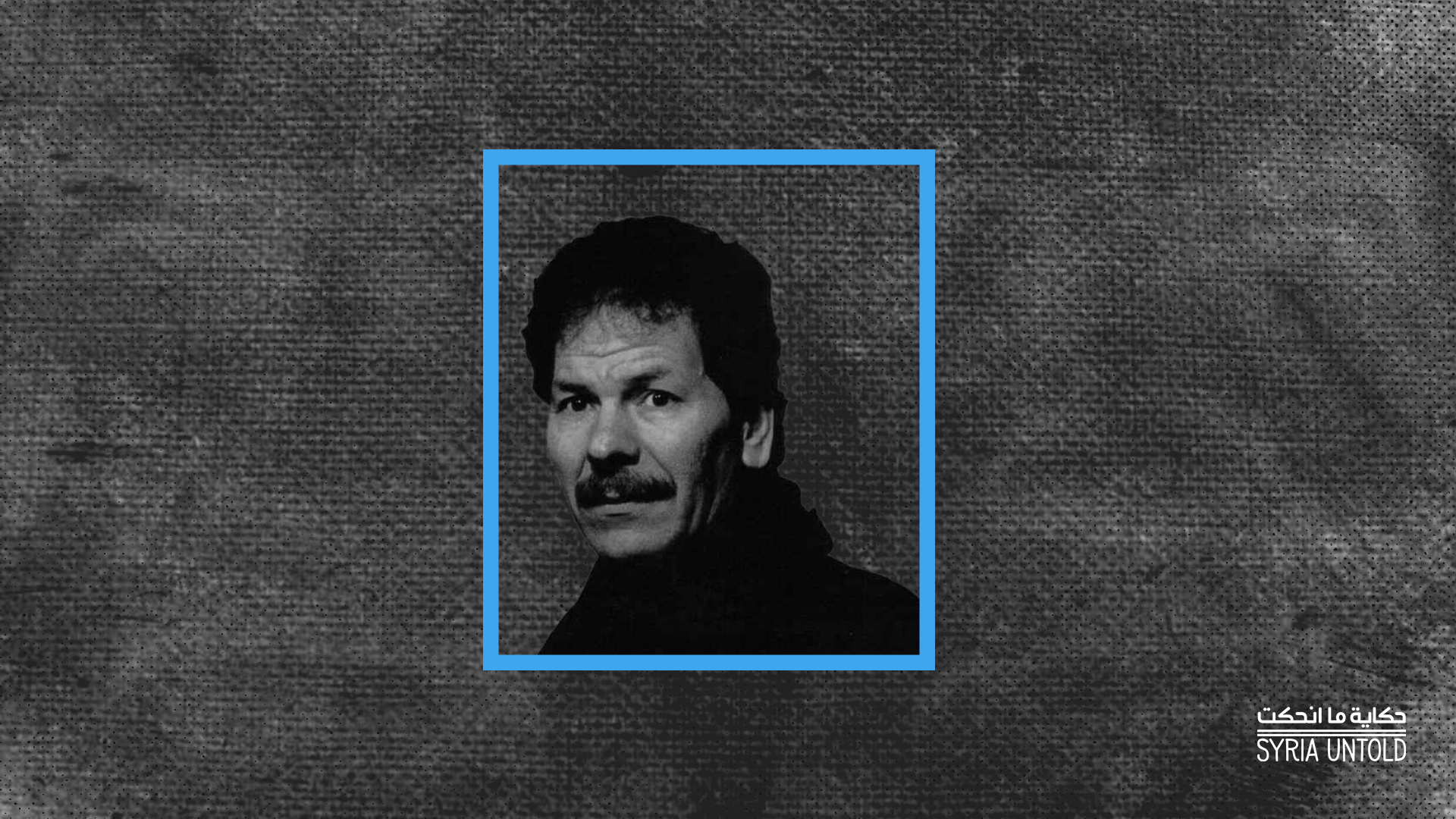

Let’s return to your film Blue-Grey. Did you employ technicians from the [government-run] General Film Organization? Tell me about the production conditions for this film, and the technical aspects. Why did you choose to collaborate with director Riyadh Shiya (1954-2016)?

First, the film had absolutely nothing to do with the General Film Organization. The film negatives were developed in the organization's labs, but otherwise, credit goes to Miyar al-Roumi, who worked on preparing the chemicals needed for development. But the film was not produced by the General Film Organization. Some friends also donated 16mm film for me to use.

I think that cinema is born from photography. The image must carry what is being expressed. An image that must be explained is not a good image. This is the rule that I kept in mind as I was working on Blue-Grey.

BLEU GRIS / أزرق رمادي from gabriel humeau on Vimeo.

My purpose when I started shooting the film was to show these tapes to my children in the future. I wasn’t thinking about turning them into a film; that was a distant dream. It was like simply taking a picture of your grandfather to hang on the wall, as a memento. I had deeply regretted not documenting the archaeological area that had been submerged by Lake Assad in the 1970s.

In the 1990s, the state completed the Tishreen Dam project on the Euphrates River, which it knew would flood wide swathes of the river basin. This made me think about documenting some of the things in that place. I had a personal desire to preserve a picture of it before the flood came and it disappeared forever. Later the film footage reconstructed what I saw. I made some of the stills in the film with Riyadh Shiya. These clips played the role of the transitions between the main scenes. Riyadh had seen the material that I had filmed so far and decided that I needed some footage to allow me to move from one scene to another. So we went out together on a journey to film those bits, and captured lots of footage.

I asked you about Riyadh Shiya because of his peculiarity in the history of Syrian cinema. His only feature-length film, Al-Lajat (1995) became one of the most distinguished films produced by the General Film Organization.

Finding fraternity thousands of miles from home, in Syrian São Paulo

25 February 2022

He belongs to the Parajanov school of cinema [Soviet Armenian film director Sergei Parajanov, 1924-1990]. Whoever watches Al-Lajat will immediately be reminded of Parajanov. I was also influenced by Parajanov and belong to the same cinematic language. Riyadh speaks through a visual language, and so do I. Most Syrian film directors studied in the Soviet Union and were influenced by Tarkovsky, who worked in the medium of “sculpting in time.” This cinematic style was also based primarily on visual language in narration. Everyone who came back from the Soviet Union wanted to make films like Tarkovsky’s, and some of their films turned out very well.

What cinematic work from among these Syrian filmmakers attracted your attention the most?

I’m an admirer of Miyar’s “silent cinema” experience. It can be said that there are Syrian films, but no Syrian cinema. There is no distinct cinematic style. If a director is allowed to make two or three films, how can he formulate his own style from just those few experiments? It’s unfortunate. In Egypt, you have Egyptian cinema, even if it is Bollywood-esque. But there is an Egyptian cinematic style, and this is due to the abundance of production. Syrian cinematic production has been paltry, and the government funneled it through the General Film Organization, which used to produce films very slowly, once every year or two. But the films that were produced in Syria were important—everything that Mohammad Malas made, Osama Muhammad and others.

Syrian film workers were cruel to each other. Omar Amiralay was outside of this circle, as he chose from the beginning to make documentary films with their own special nature and clear style. He presents his point of view, and he doesn’t mind if you agree with it. As for the others, you can say that they were influenced by Tarkovsky, but still managed to create their own cinema. For example, there was Osama Muhammad, whose film The Box of the World [translated as The Sacrifice in the English edition] even takes that title from the title of Tarkovsky’s last film, The Sacrifice (1986). There is also Mohammad Malas’ style in The Night. These directors were not given the opportunity to step out of Tarkovsky’s shadow.

Riyadh Shia had a different approach, and created something unique and special in his only feature film, Al-Lajat. It was a film based on the environment from which Riyadh came, the colors of that place and other details. I re-watched the film some time ago. It was a very poor-quality copy of the film, but even then the image retained its great expressive power. Riyadh made a fantastic film, and I hope that it won’t be lost.

In the end, after all these films made in Syria by Omar and Osama and others—who has seen them? Certainly nobody saw them back when they were made. And those who did see them only did so because they were fortunate enough to have been invited to the film premiers by the Ministry of Culture, in the Assad Library. If it weren’t for the modern technologies that allowed us to transfer these films to digital formats, that cinema would have been unknown until today. People only knew Omar Amiralay through the TV stations that showed his films, or through VHS tapes and DVDs.

Abdelatif Abdelhamid made something of his own. His films are funny and amusing, and he is certainly outside that group of more serious directors. But in the end, he still makes cinema with his own special flavor.

I was speaking with filmmaker Nidal al-Dibs recently, and he explained the situation to me at the time. He told me that there were two groups of filmmakers in Syria. The first group worked within the available margins, while the second group felt that it was impossible to work within those margins. According to Nidal, Abdelatif Abdelhamid was one of those filmmakers who worked within the margins.

As I told you, they were cruel to each other. Nabil al-Maleh was persecuted by other directors, Omar was the leader of a gang that included Mohammad Malas and Osama Muhammad, and they judged everything as either good or bad.

You worked with Omar Amiralay on the film A Flood in Baath Country. Could you tell me about that experience? Did you start making your film Blue-Grey before or afterward?

Blue-Grey was finished before A Flood in Baath Country. Also, I not only helped Omar with his film, but I helped with Mohammad Malas’ film The Night, too.

Omar had the idea of making a film against the ruling Baath Party in Syria. The script he sent me was titled Twelve Reasons Why Omar Hates the Baath Party. This was the project. Around that same time, we took a trip in our friend Mona Atassi’s Range Rover, which had four-wheel drive, to the Jazirah region. Of course, Mona blamed me after the trip for getting her car dusty because of all the dirt roads back to Damascus! We spent the night in one of those villages in the Jazirah, and Omar slept standing up. His shiny black shoes stayed shiny until we got back to Damascus. During that trip, we passed through the area where I had filmed Blue-Grey. Omar had also made a film in the 1970s about the Euphrates Dam in Tabqa, and wanted to return after all those years to make another film about the Euphrates.

After that trip, Omar said that he wanted to make the film. He tried getting the pulse of the General Film Organization, to see if they’d support the project, but I suggested instead that he make the film with whatever capabilities he already had at hand. I let him use all of my equipment alongside his own. Miyar was the director of photography and I was the driver. My main role was to facilitate Omar’s work in that region. We didn’t have any approvals to make the film, but the people there were used to my presence. I had been walking around there with a camera for years, and this helped Omar film his own project, too.

A month after shooting, I left for France while Omar decided to keep filming. After he finished the film, Omar showed me the final version. The film was very much in Omar’s style, and had a clear political message. Those 12 reasons that drove him to hate the Baath Party had evolved into 20 or 25.

But there was something missing from the film, a dramatic dimension. The school principal who Omar featured in the film, who carried out orders, was a victim like many other Syrians who live in fear of the authorities. Many of the people portrayed in the film thought it was being made by some official institution, which led them to exaggerate their glorification of the Baath Party and the leader. The main character in the film, Diab al-Mashi, had been an elected member of the Syrian Parliament since the 1950s. Al-Mashi was the region’s means of communication with the central state in Damascus. If there was any democratically elected member of Syrian Parliament, it was definitely Diab al-Mashi. If Omar had discussed these characters as victims of the Baath Party, it would have given the film additional value. I really wished the film had been better than that. Still, Omar’s film is without a doubt an important document of what Syria lived through because of the Baath Party and the authorities in power.

I’d like to talk now about the Syrian revolution—not about the political activism, but rather about the artistic work that you did at the time.

When the revolution began in Syria, I was not optimistic. My wife asked me: “Will the situation in Syria be like Tunisia?” My answer was no, because things were more complicated in Syria. I can’t say that I expected everything that ended up happening, because what happened went beyond all of my pessimism.

At the beginning, a journalist came to me and asked about the Syrian regime. She wanted to know what this regime was. Then came Bashar al-Assad’s speech, which inflamed the situation. I asked myself: “If I was in Syria right now, what could I do? And if I stay in France, what could I do?” At the time I was over 60 years old, I wasn’t a young man like you.

I found it counterproductive to go back to Syria, especially because in the years leading up to then, whenever I visited home, I wouldn’t meet many people. But if I stayed in France, I could move things through the people I knew here. Culture has an important role in France, as do intellectuals. I have many relationships with these types of people, so I thought that through these relationships we could create a form of cultural support that could turn into political support for the Syrian people. We established the Syria Freedom organization, which I led for a long time, and which became an important source of information on the Syrian revolution in the French language.

In 2014, Daesh began to receive a lot of coverage in Western media, and the world started forgetting that what was happening in Syria was a people’s revolution. I met some Syrian artists and told them about my idea to go to different towns and cities in France, occupy the public squares, and open up direct dialogues with the citizens. The idea was met with a lot of encouragement. A woman was selling her camper van, so we bought it and turned our project into the Syrian Cultural Caravan. This project, if removed from the political motives and conditions that created it, was identical to what I used to do in the Faculty of Fine Arts when I was young.

I contacted Syrian artists and writers who were enthusiastic about the idea. It was a unique experience. I researched similar projects, and only found one that had taken place in the 1950s, in Latin America. Our idea was to do a three-month tour, but when that initial period ended we kept the project running for another six years. What finally stopped us was the covid pandemic.

Let me say that revolutions do not always triumph. The idea that justice prevails is a classic one. In the end, truth is what it is, and doesn’t necessarily win against injustice. I see a lot of positives in what happened, that the people rose up for freedom, and 10 years later are still protesting against the regime and raising slogans of the revolution in areas under its authority. This is a people that has not surrendered. This is a people that is determined to regain freedom, and that is remarkable.

Those who emigrated from Syria to new societies started new lives. They remind me of the plant that I grow in my house in rural France. I look at it every day, waiting for the flowers that will emerge to decorate it. In the 1950s, more than 185 intellectuals and artists fled Greece on a single ship because of the dictatorship there. Those Greek intellectuals, artists and architects went on to make great contributions in the renaissance of contemporary Europe. I don’t know if the same will play out for Syrians or not, but what I am certain about is that they will have some role.

This conversation was conducted in July 2020. The interviewer would like to thank Sarab Atassi for researching some of the names mentioned throughout the text.