This is part two of our English translation of an extensive interview with Syrian actor Hala Omran. Read this interview in its original Arabic here.

Find part one in English here.

Hala Omran is a theater artist, actress and singer living in France. She graduated from the storied Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts in Damascus in 1994, afterward continuing her training and branching out into theater and film.

She has played several prominent roles, such as Nina in the play The Seagull by Anton Chekhov, as well as appearing in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire and numerous other plays. She has also worked with stage directors and choreographers such as Cherif, Pascal Rambert, Marcel Bosonnet, David Pope, Nolo Faccini, Suleiman al-Bassam and J. Kristanoff Saiss, Mehdi Dehbi, Olivier Letelier, Ali Shahrour and Mehdi Georges Helou.

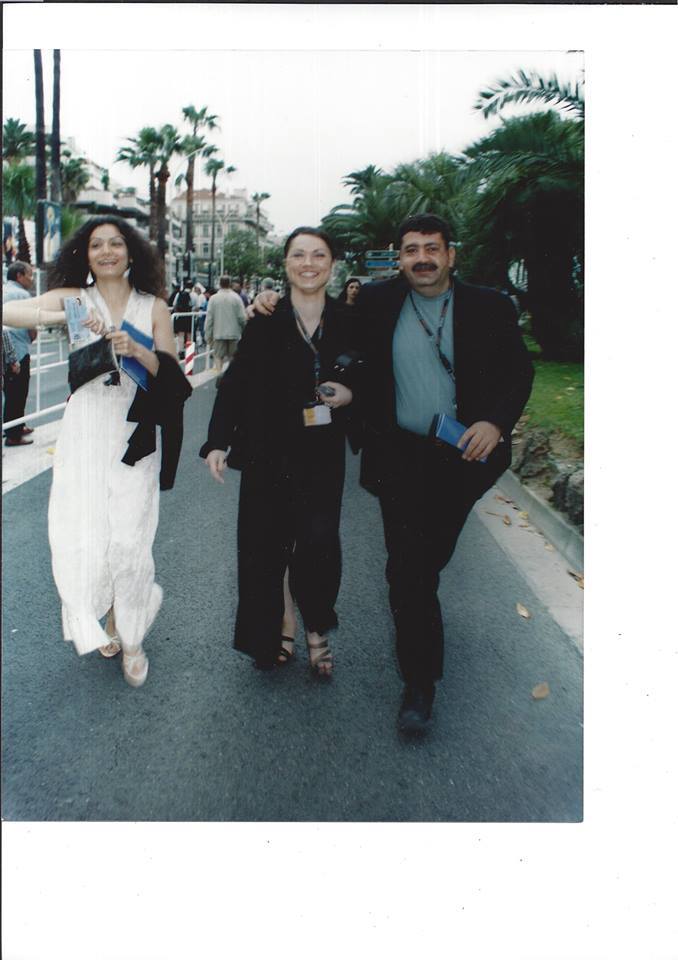

Omran has also taken on leading roles in films such as Bab al-Shams by director Yusri Nasrullah (an official selection at the Cannes Film Festival in 2004), Sacrifices by Ossama Mohammed (Cannes Film Festival official selection in 2002) and Under the Roof by Nidal al-Dibs.

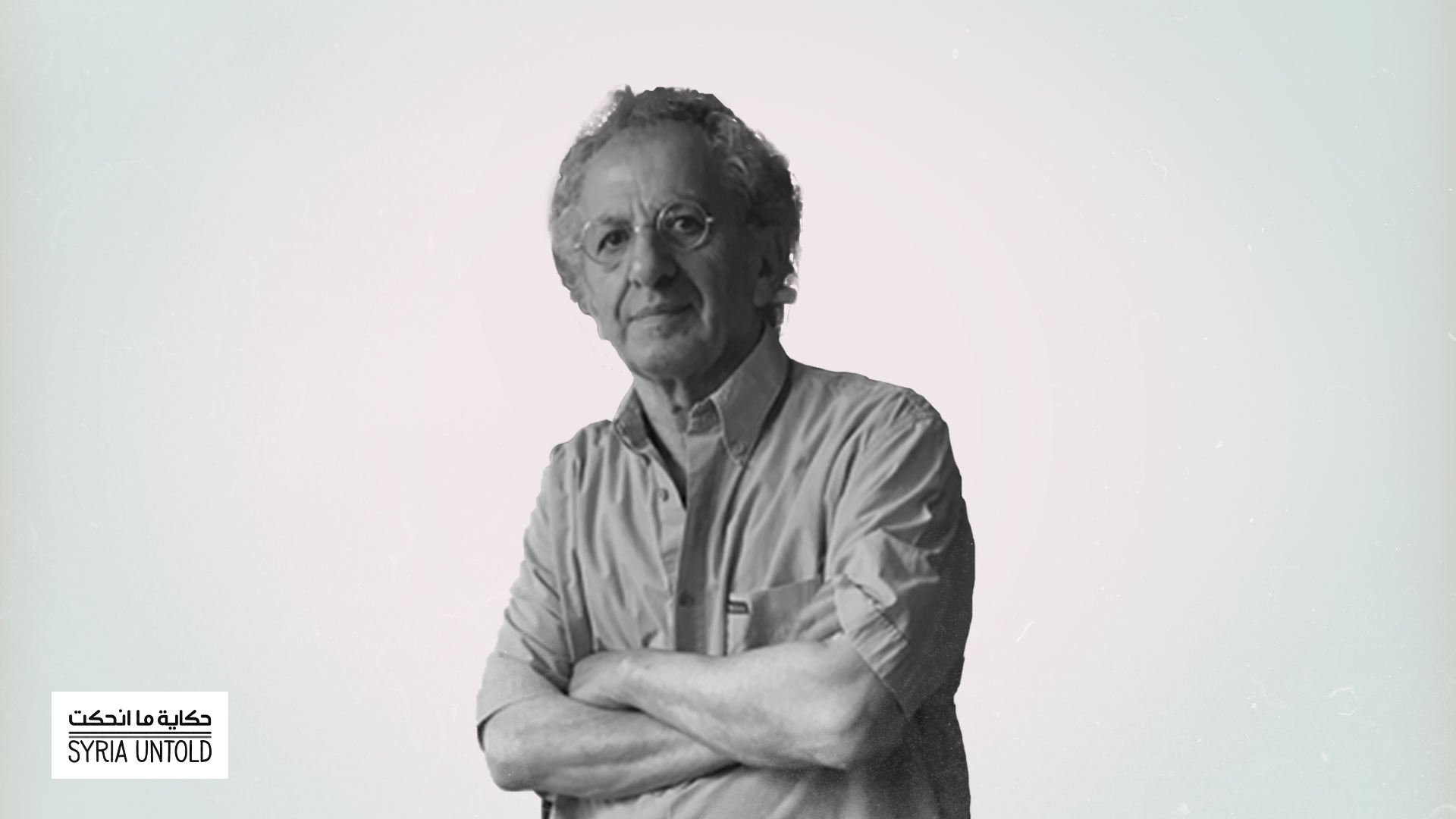

Here, she discusses her role in Sacrifices, a film set in the aftermath of a rural family patriarch’s death and reincarnation.

In a previous interview, I spoke with Syrian actress Amal Omran about the rudimentary nature of the language used by the characters in Sacrifices, and how this is a profoundly significant feature of the film. Could you tell me more about that language? Where did it come from?

It was indeed a very simple way of speaking. The direction came from Ossama: These characters should be lizard-like, resembling reptiles or snakes. It was something entirely instinctive and sensory rather than intellectual. For example, my tongue-tying in the film was reminiscent of the way lizards move their tongues. The woman I portrayed is not insane, but rather primitive and closer to the animal world than to humans. But at no point did we treat that character as insane. Ossama did not think of her that way, and neither did I. Rather, she is a primitive woman who doesn't know how to speak and never learned how.

This character only utters a few words, repeating those words throughout the film. She’s heard those words before, so she repeats them. She is in a constant state of discovery. For example, there is a sexual scene between me and Zuhair Abdelkarim. In that scene, Zuhair is in a tree while I’m standing below him. He reaches out to touch my chest. In that scene, my character is discovering sex for the first time. It was something merely sensory. Those styles of working intersected with my own tendencies at the time in training myself as an actress, as I was doing a lot of meditation, breathing and body exercises.

I agree with you that the character you played is not insane. Perhaps she is more innocent than the other characters, but seems to be the most connected of them to the metaphysical world.

She has a connection with nature, and this is what endows her with the ability to communicate with the metaphysical world. This woman comes from an unknown place, and the other characters in the film see her as savage and primitive. However, this character is the one who will come to hold the true authority because she is the mother of the child who is the reincarnated spirit of the [family’s] deceased grandfather. The boy will come to have absolute authority over the house and whoever is in it. You will see the transformation of that primitive and naive character into an authority figure, and even someone who manipulates the other characters through her usage of that power.

My thoughts, my body, my feelings, my knowledge and memory—it all revolves around the work that I do.

It is clear that this character, as she is presented in the film, comes from a family with a lower social status than the others.

Much lower. She is the daughter of the mule thief. She comes from that background to a position of authority. We notice this in the change of her eye movements following the reincarnation of the grandfather’s spirit in her son’s body. This rebirth prompts her to believe that she now has power, as she is the one who gave birth to the sacred reborn spirit. Her character transformation is a magical one. And it is an essential part of what the film and its filmmaker wish to say about this world, this sect, these characters, their human and behavioral transformations.

How did you perform your character alongside the other characters in the film? How did you build that rhythmic harmony through movement and performance alongside your fellow actors, bearing in mind that your character and her son were social outcasts?

Ossama felt it necessary to have all the actors present at all times on the set. It wasn’t the usual situation, where you come just to shoot your scene then leave when you’re done. We were present during the entirety of filming, as we are when performing theater. We were there anytime the camera was on, day or night. The relationship arose because of this.

You were watching each other’s scenes during filming?

Exactly. Almost everyone did. There were also many ensemble scenes in the film. True, the character I played was living in a tree outside of the [family] house. But she was present in almost all of the ensemble scenes.

Mohamad Al Roumi: Cinema is always necessary

11 March 2022

Soudade Kaadan: 'Magic realism sneaks into all of my films'

19 July 2021

There was one beautiful scene in which we were kneading animal dung with our feet in order to cover the interior walls of the dilapidated mud house. It took a long time to film this scene. We were shooting in such high temperatures that Amal nearly fainted. It was hot, and the mud we were kneading was also hot, with worms coming out of it. That was because we had left it out for more than a day as we tried to finish the scene. All of this instilled a sense of intense closeness and a spirit of unity in our work.

The way Ossama created the cast created that feeling of automation and communication that appears in the film. You have to see the script as it was written. The rhythmic feelings of the scenes are palpable and clear in the written text. You just have to execute this script well, and that’s what happened. Ossama was running the process as it was in his head, and as he wrote it in in the script. This is what produced such harmony between sound and movement. The movement in the film was not improvised. Everything was drawn carefully. And we practiced often in order to achieve the structure that Ossama wanted from each shot.

Tell me about the scenes in which you interact with the girl who played the role of Fairouza. I find those scenes to be very important to the film. After the grandfather’s spirit settles into his grandson’s body, the mother (your character) attends to all her son’s needs as if she’s a servant of the king.

Not only that, but she is also beginning to see herself as the master of everything, that she is entitled to that position. Indeed, those scenes with the girl who played Fairouza were amazing, as was the actress herself. I don’t know where she is today, but she and the other child actors were all amazing and she was exceptionally charming.

That young actress was the daughter of the bus driver who was responsible for transporting the actors in the film.

Yes, I think that’s right. I know that they brought her along with other children from the villages near the filming location. They died her hair red because she was supposed to be a beautiful witch. I don’t know if Ossama was fully intentional about everything in our scenes together, but there was a sexual aspect to some of those scenes. Something ambiguous about the woman character’s relationship with Fairouza.

That ambiguity was clear—it left the audience confused over whether the woman wanted Fairouza for her son or for herself.

Exactly. This wasn’t clear from the text, and it was not 100 percent intentional, and there was no direction from Ossama to read the two characters’ relationship that way. But I’m sure that it arose from the way that the scene was written.

When we finished filming, Ossama called to tell me that in one of those scenes with Fairouza, I had a very expressive voice, something that was neither written nor required of me. In that scene, my character approaches Fairouza and grabs her. Fairouza says to her: “Stay away,” and then leaves. Then a strange sound then comes from me, an animal, inhuman sound. You can interpret that sound in several ways. All of this came because we were working on a character with unclear desires. The woman understands that her son desires the girl, and to that end she begins working on achieving that desire for him. In doing so, she gets closer to Fairouz in order to become her friend. The character I played has no understanding of the age difference between herself and Fairouza. Indeed, she herself is still a child. A child in a woman’s body. And because of her sense of her own childishness, she accepts that she is trying to play and laugh with the girl and wants to become close to her, become a friend. Within that relationship arises desire and longing.

Acting is my life and nothing else in this life has the same value.

Meanwhile, your character’s relationship with her son changes after the reincarnation occurs, as the son becomes the one in control, no longer beneath the authority of his mother.

Her son has become the master and he begins to treat her with the kind of contempt that you see in hierarchical traditions—that is, that woman are despised in some positions within the hierarchy and they are barred from receiving religious teachings and other things. When the boy ascends to the throne of power, his mother becomes something wretched. At the same time, she is happy to be that wretched person, as she is the master’s mother.

The closest outcast to the master.

Exactly, the outcast closest to the seat of authority.

Within the margins, and breaking free: Syrian cinema

23 January 2021

For more than a year, I’ve been asking the question: Is there such thing as a cohesive Syrian cinema? Or, rather, are there just individual Syrian films? It’s a question I’ve asked Nidal al-Dibs, Mohamad Al Roumi and Amal Omran, and I’ve even spoken at length with Ossama about the topic. The answer is no longer important to me. Each film has its own experience and technical conditions.

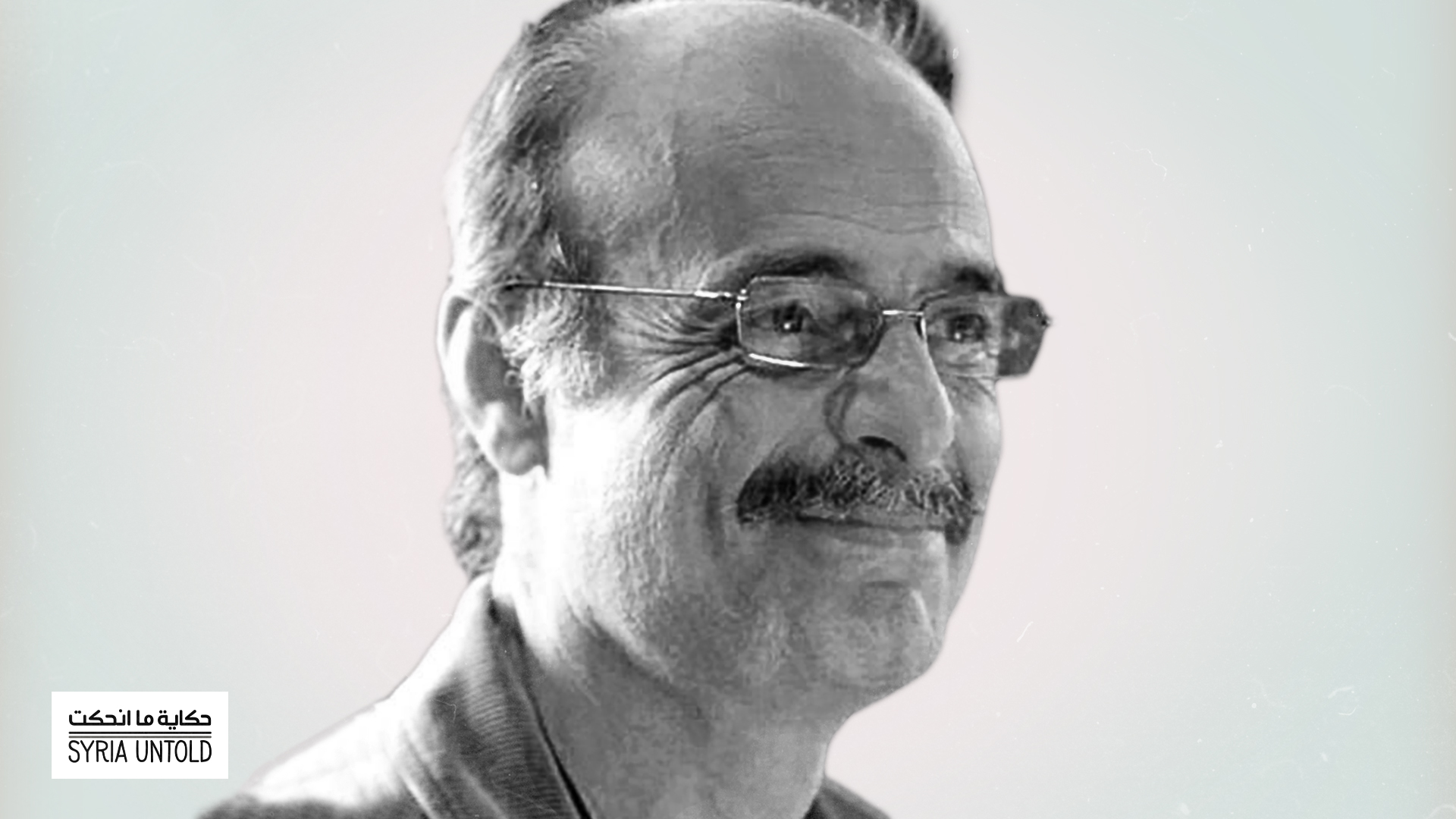

How do you see your experience with Sacrifices? How do you evaluate your position as a Syrian artist who is familiar with other Syrian cinematic experiences? Nidal al-Dibs has described Ossama as a cinematic Sufi mystic, someone who gives himself completely to the project on hand and expects all those working with him to do the same. Nidal is clear in rejecting Ossama’s approach, despite his appreciation for it. Can you compare your experiences with Ossama and with Dibs, in whose film Under the Ceiling you also had an acting role?

What you said about Ossama is very true, and it’s what made me happy with my experience in the film. It’s also what created a sense of understanding between the two of us as director and actor. I am like Ossama, in that I give myself fully to my work. Acting is my life and nothing else in this life has the same value. I presume that the people I work with have the same point of view.

And so my artistic experiences are limited to people who think and work the way I do. For example, in the theater I’ve been working with the same two people for around six years: Suleiman al-Bassam and Ali Shahrour. I work with other theater artists, too, but mainly I’m with these two people whose work ethic mirrors my own.

I cannot work on a project unless I’m fully engaged with it. My thoughts, my body, my feelings, my knowledge and memory—it all revolves around the work that I do. Ossama is the same way. We both have something of an obsession with what we do, which is the beautiful thing about working with him.

Sacrifices has great meaning for me. It was the first film I worked on, and it was the first Syrian cinematic work to be featured at the Cannes Film Festival, among the festival’s official selections. Regardless of whether or not Ossama’s film is a Syrian film, it has an elevated cinematic language in terms of cinematography, poetics and intellect. It is not an ordinary film in my opinion. And it is not an easy film. You need knowledge of the symbols the film was built on, which is why I understand why some people didn’t grasp the film or its story. There were a lot of people who thought the film was too complicated. But I think you can still connect with the film without understanding all of its symbols. Surely you can capture some of its meanings from the first viewing; there is something sensory that will reach you, at the very least from the cast, the colors, lighting or movement.

Among the Syrian films produced by the National Film Organization, I consider this one to be the most distinguished in the history of that cinema. I wasn’t a part of the film The Night by Mohammad Malas and Ossama Mohammed, but I can say that there are aspects of The Night that resemble how Ossama works.

Those same aspects were present in Under the Ceiling as well, as Ossama was a part of that experience and impacted it. Under the Ceiling is, without a doubt, a Nidal al-Dibs film, but Ossama provided advice in many areas such as casting and performance. Ossama’s presence on the set of Under the Ceiling gave me a lot of confidence, as I didn’t know Nidal well as a director at the time. I felt that confidence because Ossama knew how I worked and how to motivate and connect with me. Yes, I think Ossama’s influence is very evident in the films in which he collaborated artistically with other directors.