This article is part of a dossier in partnership between SyriaUntold and Orient XXI, exploring the consequences of the devastating earthquake that struck Turkey and Syria in February 2023.

From a Syrian mother's perspective, an architect and human rights advocate working in the field of humanitarian response and rights for those affected by the conflict in Syria, this article provides a narrative analysis of the most significant factors that made the devastating earthquake in northwestern region of Syria not the first earthquake or catastrophe to disrupt and shake the infrastructure and social fabric of the population there over the past twelve years. Instead, there is a long, multifaceted series of factors and issues that have contributed over the past decade to creating a fragile urban and demographic structure vulnerable to any disaster, whether material, psychological, or humanitarian.

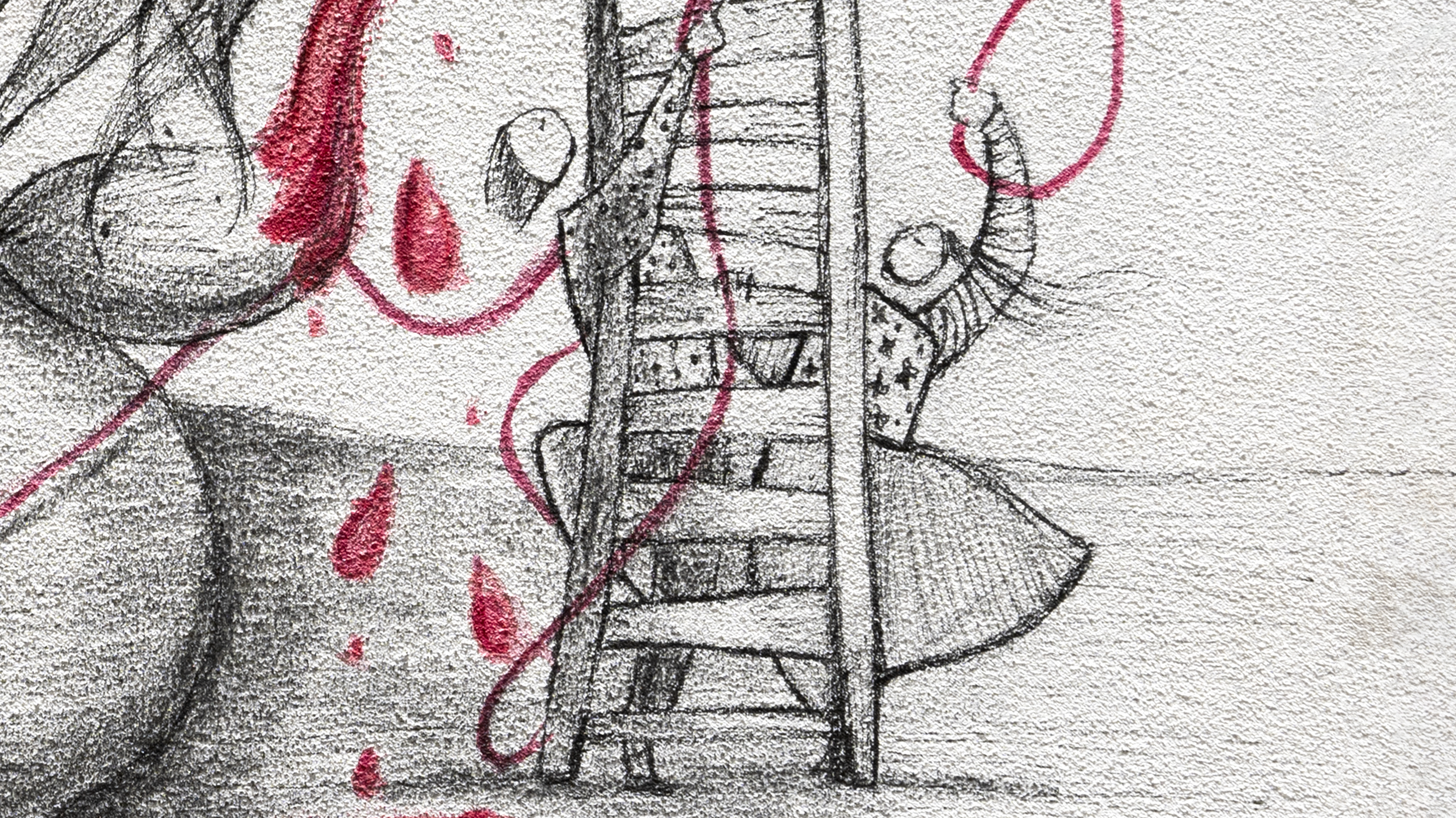

I love drawing, especially faces, particularly women's faces. I sit there at my usual table in my beloved room and passionately draw them, as if I'm sketching all my feelings in the details of their eyes. I didn't realize that my talent was inclined towards those faces until I found myself here, sitting at decision-making tables, discussing the details of humanity from women's perspective, from their eyes. It was not a coincidence!

Also, it was no coincidence that I studied architecture. I knew very well that it's not just about building bricks and designing structures. Rather, it's a complex human relationship that began with drawing faces and extended to my relationship with my room. It was a friendly relationship filled with secrets, passion, and love, and it ended with the first shell that took my room away, leaving me with few memories, like all Syrians.

It was no coincidence that I studied architecture. I knew very well that it's not just about building bricks and designing structures. Rather, it's a complex human relationship that began with drawing faces and extended to my relationship with my room.

My room and drawing taught me that architecture is a human relationship to create life in an empty space with its dimensions, measurements, and material and physical needs. It's also a human need to feel belonging, starting from a small space that represents us and satisfies our sense of belonging, going all the way to our love for our personal space and homeland.

However, my homeland today is filled with nothing but destruction. I'm not talking here about piles of stones and rubble, but about the distances that forcibly separated the body from the soul. We, the displaced, believed it to be a safe distance. The truth is, we were mistaken in thinking that all horizontal and vertical distances, across seas and continents, could succeed in uprooting our souls from that land. My soul still lingers in the void of my room almost every night, as if the twelve years of war unfolded outside the spatial and temporal dimensions of this universe!

Migration due to differences of opinions

I was lucky to visit my homeland recently, after a ten-year absence from the land called "Syria." I crossed the Turkish border into northwestern Syria, where the stronghold of forced displaced people is located, coming from all over the country. I met people I had never met before, walked, and sat in places I had never set foot in. I slept under a roof that wasn't my room since I left that beloved architectural space in Homs.

My focus was on the faces of the women I met. They were like the black and white portraits I used to draw. Beautiful, strong, and fighters. Nothing has changed in these faces. What has changed is our ability as women to endure and persevere. We have created new roles for femininity that we never thought we would be capable of after this displacement.

What has changed is our ability as women to endure and persevere. We have created new roles for femininity that we never thought we would be capable of after this displacement.

Women paid a heavy price for this, with no gender exceptions here. They fled with those who fled and were arrested with those who were arrested. The ideal choice for them wasn’t internal or external migration, but they were forced to do so because they were suddenly labeled as criminals and terrorists along with their families. They fell under the curse of security persecution and targeting by the Syrian regime.

Nevertheless, Syrian women did not just settle for the role of mothers and housewives. They rather became mothers carrying the cause of other women as well as their own. Since 2011, when they began altering the Syrian political and humanitarian climate, they have started expressing their opinions and standing side by side with their fellow countrymen in determining their fate. Until now, Syrian women's struggle intensifies day by day to express their opinions and shape the country's destiny, especially since they are the most affected among the population.

On the 6th of February, at precisely seventeen minutes past four in the morning, it was not the first time that Syrians heard cries, screams, and people fleeing their homes and losing their loved ones.

The Impact of Forced Migration to Supposedly Safe Areas on Human Urbanism in Syria

When the United Nations decided to establish a safe crossing zone in northern Syria, its aim was to preserve the dignity of displaced people and protect them. The importance of studying the reconciliation process lies in the fact that it represents one of the most complex aspects of the Syrian crisis. It intersects with international, regional, and local political and military dynamics on one hand, and the social structures of areas that were outside the control of the regime on the other. Therefore, the numbers continued to increase, reaching several million in northwestern Syria and southern Turkey. Did the United Nations really succeed in achieving its goal of protecting displaced civilians and preserving their dignity there, especially women and children who faced danger, violations, and deprivation of their basic rights, such as education, healthcare, food, and shelter?

Many civilians were also forced to leave their homes and homelands due to evacuation agreements between the conflicting parties or due to the opening of humanitarian corridors facilitated by the United Nations to evacuate civilians from conflict areas. Often, these operations were accompanied by violations of human rights and international law.

February 6th Earthquake: How do we understand what happened and where are we today?

14 July 2023

The Arts of the Earthquake

11 August 2023

The main concern of these displaced people was, and still is, to find a safe and dignified place away from the horrors of war. They fled by millions to escape war and violence against innocent civilians that the country has witnessed since 2011.

Today, more than 4.5 million people, mostly internally displaced, including women and children, live in northwestern Syria, in a small geographical area designated to accommodate only half that number. This overpopulation significantly affected the shape of Syrian cities and villages. The infrastructure in northwestern Syria was not equipped to receive this multiplied number and these traumas.

Dealing with these traumas and repairing the damage caused by this ongoing war was not easy. Yes, ongoing, because every year there's a new disaster in this place, and the earthquake was not the last. The region is so fragile that poverty, unemployment, hunger, and ignorance levels have been increasing year after year. Despite all this, the people there, few of whom I have met, are creating life and resilience out of nothing. Syrians are urban people by nature, they've inhabited and developed that region for thousands of years. Today, despite the high cost, especially for those who were forced to live in camps, they are capable of struggling to secure their livelihood.

It cannot be denied that this phenomenon in northwestern Syria has had an impact on the demographics of the region and on the urban landscape as well. Everyone seeks a form that expresses his or her identity and specificity in shaping the place. The differences in environments have led to a clear change in behavior and the way of dealing with news in the first place. In brief, poor humanitarian and living conditions, coupled with a condescending view from certain individuals in the region, has driven people to create introverted spaces primarily defined by their utility. People's needs were certainly not the same, but securing housing was the most basic need, regardless of the spiritual and psychological need for comfort. The Syrian city has lost its character, identity, and continuity. The image of the present is different from the past, especially recently after the devastating earthquake.

After the earthquake, the situation in the north became worse. The connections to that area were cut off, as if it didn't exist for several days before the disaster. Death often become their companion, for those who didn't die under the bombardment of planes, missiles, and barrel bombs died under the rubble of the earthquake, or perhaps while fleeing from life. Perhaps all those who died had miraculously escaped life before that.

This land is smaller than the blood of its children

standing on the threshold of doomsday like

sacrificial offerings. Is this land truly

blessed, or is it baptized

in blood

and blood

and blood

which neither prayer, nor sand can dry.

There is not enough justice in the Sacred Book

to make martyrs rejoice in their freedom

to walk on cloud. Blood in daylight,

blood in darkness. Blood in speech.

Mahmoud Darwish

All these years, Syrians have not been convinced that they might no longer have a homeland, perhaps just fragments of it. It has become so terrifying that returning to it, whether as a refugee or an internally displaced person, is seen as a threat. This has contributed to limiting access to economic, social, and cultural human rights.

Families there have been deprived of one of the most essential aspects that housing provides for a person, which is the very first thing I learned in house design during my first year at university: "privacy." To have a private space that protects you, shields you, and reveals only what you choose. In contrast, what a tent or a camp offer is revealing yourself to your entire family, then to your neighbors, and even to strangers who you may or may not know.

As for their living environment, you find schools made of fabric, roads made of dirt, hills and valleys often filled with sewage residues for which engineering solutions remain elusive to this day. We are talking about nearly two million people living in residential complexes in cities on the outskirts of roads, in tents, cement rooms, or caravans. Why? Because displacement has not stopped until now. Yet, waves of internal displacement have not been recorded as forced migration for years! The people of Daraa, Homs, the countryside of Damascus, Aleppo, and Idlib were displaced once. But after that, their subsequent internal migrations were registered as population movements from one area in the north to another to earn a living, work, family, and in some cases, due to conflict and battles. These migrations are not random, as one might imagine.

What does targeting a hospital mean?

I wonder what does it mean to you when a hospital providing healthcare to the residents in an area is targeted? Once, twice, ten times? What message do the people receive when vital points like hospitals and schools in that area are targeted? People have been forced to repeatedly flee and seek a safe haven in a small geographic area, fearing death due to the bombing of a nearby hospital or school.

In the latest brutal attack by Syrian government forces of the al-Atarib Surgical Hospital in northwestern Syria - a fortified hospital referred to as the "Cave Hospital" because the architect proposed building it as a cave to protect it from shelling-, guided missiles struck the front and rear entrances of the hospital, where people usually gather, waiting for their loved ones.

This happened on a spring day in March 2021. Seven civilians, including children, were killed, and more than 12 people, including medical staff, were injured. The destruction of an urban hospital in a Syrian context has far-reaching destructive consequences beyond the targeted physical space. Escalations against humanitarian and health facilities have always been accompanied by new waves of displacement. How can people secure their lives in their homes when they live next to a space designed to save lives but was hit by a guided missile?

The Socio-Economic Ramifications of the February 2023 Earthquake in Syria

19 July 2023

Turkey Targets INGO Workers and Foreign University Staff, Students

26 June 2017

The hospital's director, who is also an architect, is trying to fortify the place, especially the entrances. Perhaps, he has taken every possible precaution now. But I fear that it might be too late. Holding the perpetrators accountable today is the first step towards justice, and then all other methods come afterward. I know it is a distant matter, and perhaps the world's continuous indifference to these crimes over the past decade warns that this is probably impossible. The war in Ukraine is the first consequence of that neglect and the impunity for all criminals! All of this means that people in northwest Syria are pursued and unprotected.

At the beginning of the war in Ukraine, Marc Coates, then Deputy Humanitarian Coordinator for the Northwest Syria office, asked me for advice as Syrian women. We offered advice to the United Nations/ OCHA office in Ukraine regarding the establishment of humanitarian corridors for civilians there. At that time, came to my mind a series of forced displacements’ events that took place under the cover of humanitarian corridors in Syria, such as the displacement of the residents of major Syrian cities, Eastern Ghouta, Daraya, Homs, Aleppo, and Maarat al-Numan. The witness to those crimes was ignorance and betrayal. The displaced didn't know how long their absence would last, what would remain of their homes, or what awaited them in the safe zone. Humanitarian corridors transformed the issue of people's migration driven by fear and the threat of death in northwestern Syria from protecting their rights and dignity to monitoring their growing needs and requesting financial donations to cover them. This was not in our minds back then. Even our subconscious clung to the idea that we are still there, in our homes, and have never left.

We have been forced to be ignorant of our fate for all these years, and until now, we ask: How did this happen, and why? It is important for us as humanitarian workers to be able to repair all those errors related to our unawareness of our rights to lead and participate in shaping our lives, including our food, our homes, and even the bridges through which we facilitate assistance and communication with others. The latter certainly need additional architectural skills!

As architects, it became imperative for us to enhance our skills in bridge-building, extending beyond mere design creativity and calculations of the necessary materials like cement and steel, or assessments of the forces at play and their reactions. Some bridges require negotiations and powerful political and humanitarian stances, allowing them to withstand the impact of earthquakes or wars. These bridges should remain a safe passage for the exchange of skills, goodwill, and cultures among humans, transcending borders and time. Migrations, regardless of its causes, is the fate of humanity. That earthquake has not yet ended. It seems to persist to teach us that this country has truly returned to ground zero and needs to be rebuilt, starting from that threshold.

New doors to life will open in this place, for “we love life if we find a way to it”.