"He is Kurdish, but he writes in Kurdish!"

This statement may seem peculiar, as it is natural for individuals to write in their native language: for a German to write in German, for a French person to write in French, for a Spanish person to write in Spanish... However, it is not customary for a Kurd to write in the Kurdish language.

Most Kurdish writers choose to write in the language of the country they were born in, lived in, and hold citizenship of: Turkish Kurds, like Yaşar Kemal, write in Turkish; Iranian Kurds, like Ali Mohammad Afghani, Mansour Yaquti, and Qutb al-Din Sadqii, write in Persian; Iraqi Kurds, like Buland Al-Haidari, Tahseen Garmiani, Gulala Nouri, and others, write and have written in Arabic. This is also the case for many Syrian Kurdish writers who write in Arabic, and have contributed to the Syrian creative scene through novels and poetry, enriching it significantly. They are so numerous that they constitute almost half of the writers in Syria. Among them are noteworthy figures like Salim Barakat, Muhammad Afif Al-Husseini, Jan Dost, Haitham Hussein, Luqman Dirki, Marwan Ali, Delair Youssef, Reber Youssef, Widad Nabi, Maha Bakr, Ibrahim Mahmoud, Nizar Aghri, and others. Interestingly, there are also famous writers who, often without our notice or knowledge of their Kurdish origin, write in Arabic, such as the renowned poet Ahmed Shawqi, known as the Prince of Poets.

Is it Arabic literature written in Kurdish or Kurdish literature?

There is a heated debate regarding the categorization of literature written in Arabic by Kurdish authors. Some perceive it as Kurdish literature written in Arabic, while others contest this classification, as mentioned by the translator Ibrahim Khalil, who translates from Arabic and French into Kurdish. He currently teaches in the Kurdish Language and Literature department at Rojava University in Qamishli. He explained in one of his interviews, addressing the "problem of defining the identity or classifying the works of writers who write in a language other than their mother tongue": "The matter is more obvious than you imagine. Shakespeare is an English writer because he wrote in English, Victor Hugo is a French novelist and poet because he wrote in French, Saadallah Wannous is an Arab playwright because he wrote in Arabic, and Bachtyar Ali is a Kurdish novelist because he writes in Kurdish."

New Syrian cinema: Young and gasping

14 January 2020

Syrian cinema: Motion picture in the age of transformation

14 April 2020

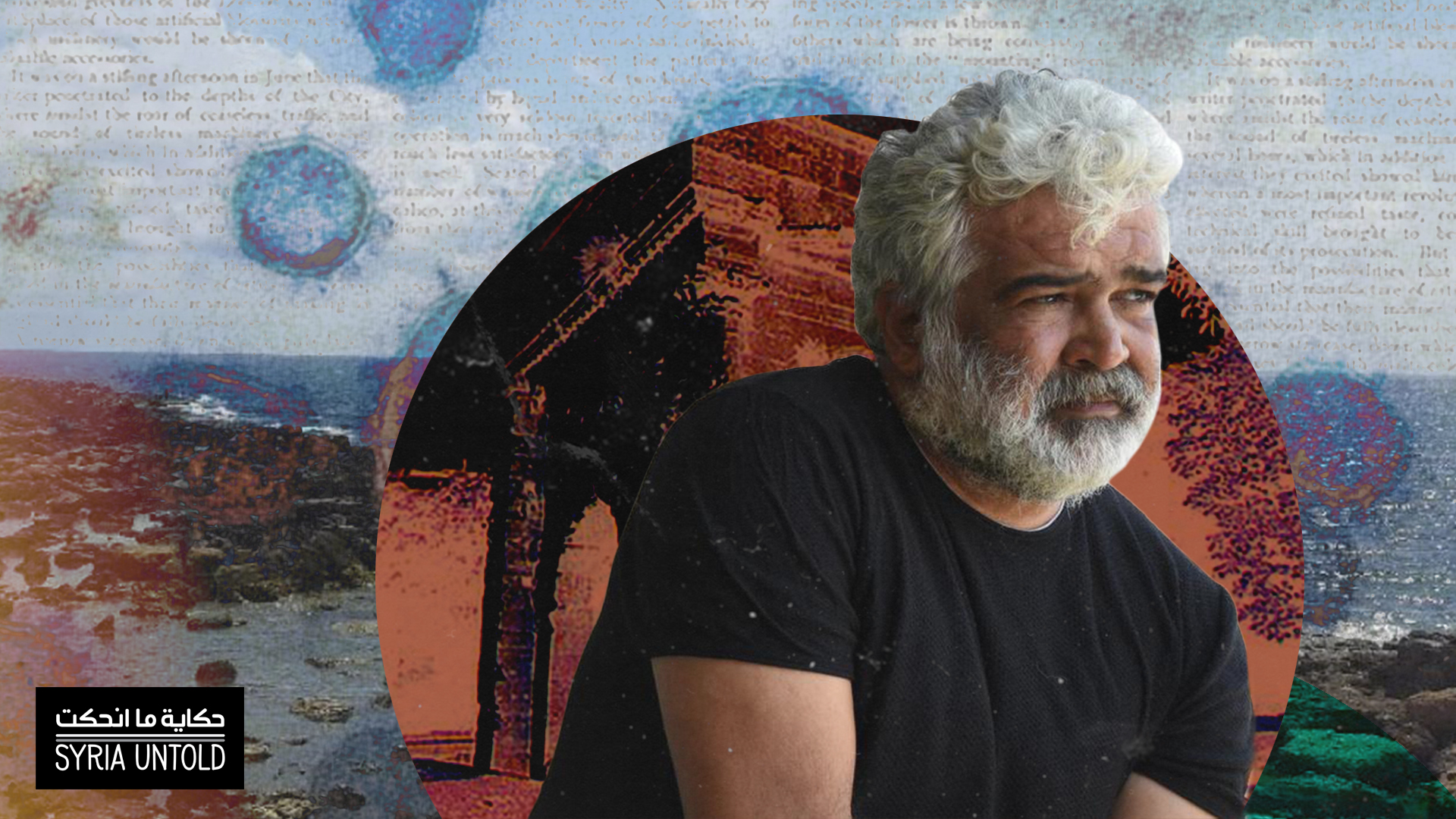

In a similar vein, the Kurdish novelist Halim Youssef* tells me that he initially began writing and publishing in Arabic while residing in Syria. However, after relocating to Germany, he transitioned entirely to writing in Kurdish. His recently translated novel from Kurdish to German, "Ninety-Nine Scattered Beads," is considered a pivotal event in contemporary Kurdish literature. The novel was recently released with a translation by Barbara Sträuli from Sujet Verlag publishing house. He explained, "Through my experience, I noticed that the majority of Arabic publishing houses orbit around Arab authorities and favor Arabic works by writers of Kurdish origin. It is amusing that these publishing houses, along with some cultural magazines, market these Arabic works as Kurdish literature. Here, I wonder by way of assumption: What would be the feelings of Arab writers if a cultural magazine published a feature on Arabic literature including the works of the writer Rafik Schami? Wouldn't this, if it were to happen (which is unlikely of course), cause everyone to ridicule it? This is exactly what happens in the Arab cultural circles; they present Arabic literature to readers as Kurdish literature. Meanwhile, Kurdish literature remains absent from the Arab cultural scene and marginalized, as if it does not exist."

Halim Youssef emphasizes that the identity of the literature we write is defined by the language it is written in. However, he also affirms his respect for the choices of all writers in choosing the language they want to write in, whether it is their national language or another language.

But the novelist Redi Masho* disagrees, saying: "Regarding the identity of the literature written by Kurds in the Kurdish language, it is an eternal debate. Even Arab writers who write in French are not exempt from it. Anyway, my judgment is questionable because I am Kurdish first and foremost and secondly because I am a writer. For me, it is more appropriate to judge the work by its quality, but it seems that this is not the case, especially in the age of nationalist sensitivities. In the end, I say that Kurdish literature written in Arabic only uses the Arabic language, while the spirit and pulse are Kurdish. The truth is that readers are the ones who judge in this matter. Everyone knows us, you and I, Khalid Hussein, Haitham, and others, as Kurdish writers, and they recognize our literature as Kurdish literature written in Arabic."

Why do Kurdish writers, who are proficient in the Kurdish language, choose to write in Arabic?

This is a question that many of us find intriguing: Why do Kurds opt for Arabic in their writing?

Novelist Haitham Hussein* responds by saying: "Writing in Arabic was not initially a choice, it came naturally. Arabic was the language of instruction at every educational stage, and all the scientific, literary, and intellectual accumulation came through the language of education and through education. Then came the intellectual, philosophical, literary, and fictional readings in Arabic. This means that Arabic became my mother tongue in terms of knowledge and literature. Mastering it after years of study, and eventually becoming an Arabic teacher, was a dedication to its position in my crystallization as a Kurdish writer who writes in Arabic. Kurdish, for me, remained in a familial, social, and popular space for me. However, it did not turn into a language of knowledge. All my readings in it do not go beyond poetry collections, stories, and novels. It is my spoken mother tongue, but it is not the language of knowledge and literature."

He also describes his experience in learning to read in Kurdish: "I learned to write and read in Kurdish on my own, and I did not receive any lessons in Kurdish in my life. My reading and writing in my language are based on personal efforts. Although it is my mother tongue, the one I speak at home with my family and relatives, it is not easy for me to write in it as I do in Arabic, with the same ease, comfort, exploration, and elevation. Arabic is my mother tongue in terms of writing, thought, and literature. I read all my readings in it over more than thirty years. This human legacy cannot be easily relinquished or erased as if it never existed. All of this shapes my personality as it is now and contributes to crystallizing images of my identity, which, as a writer and a human, is open to identities, enriched by them."

Syrian theater through a decade of war

01 June 2021

Current conditions of Syrian theater

28 May 2021

In a similar vein, novelist Redi Masho responds: "Proficiency in speaking Kurdish does not mean that I am proficient enough to write a novel in it. This holds true for most of my peers as well. I know how to write in Kurdish to an extent that allows me to write short prose pieces, but when it comes to the novel, it's different. All my literary, philosophical, scientific, and historical knowledge was acquired in Arabic." He adds, "I have two prose collections in Kurdish, and perhaps I'll work on them later, provided I find the energy, and, of course, my command of the Kurdish language must be improved for that."

Why did some Kurdish writers turn to writing in the Kurdish language?

The novelist Halim Youssef shares his experience of writing in both Arabic and Kurdish, and his ultimate decision to exclusively write in Kurdish: "I was born in Amuda to parents who spoke solely in Kurdish during their entire life. My first job was as a translator for my father, aiding him in dealings with government offices and employees who were unfamiliar with Kurdish. Similarly, I assisted my mother when Arab women visited our home. Their Arabic linguistic knowledge was limited to reciting Al-Fatiha (the opening chapter of the Quran) and essential vocabulary for prayers, and this knowledge was only applied during prayers. In our house, even the religious invocations recited by my parents after prayers were in Kurdish.

My father, who went to Mecca three times and performed the five daily prayers for seventy years, returned home every Friday from the mosque visibly upset after attending the Friday sermon delivered in Arabic, as the imam of the Grand Mosque in Amuda was forced to do so. I remember him declaring one day, 'If God were truly just, He would have revealed our Quran in Kurdish as well. Given his omnipotence, why not address all peoples in their own languages? If God is unfair, how then can we blame governments and states, mere mortals, for this?' And a few minutes later, he would seek forgiveness from God, asking for immediate relief from his outburst of anger.

It was within this peculiar atmosphere that I, along with other Kurdish children, were raised. It was made possible for us to learn and master Arabic, both reading and writing. Meanwhile, Kurdish remained an orally transmitted language, failing to make its way onto paper. I started literary writing at a young age, in the language I had learned, which was Arabic. I turned primarily to writing out of a spiritual necessity. In the stories I wrote, I found myself depicting the environment I belong to, which is Kurdish, and crafting characters who originally speak Kurdish. I resorted to translating their dialogues into Arabic when writing. Simultaneously, I had secretly learned the Kurdish alphabet at home. Occasionally, we'd obtain Kurdish literary books that people circulated discreetly, far from the eyes of authority and intelligence. My Kurdish literary language improved. Therefore, I consider returning to writing in Kurdish for me as a return to my authentic essence, after the policies of prohibition and oppression towards my mother tongue had distanced me from my soul, and tried to strip me of my natural cultural heritage bestowed by nature. The normal state is for the Arabic writer to write in Arabic, the Kurdish writer to write in Kurdish, and the French writer to write in French, and so on. Therefore, my return to writing in Kurdish was a return to the normal state, and a liberation from the exceptional circumstances imposed upon us by the tyranny, chauvinistic, and racist policies of the ruling regime in Syria."

Halim Youssef's experience resonate with that of Hussein Habash*, who made a resolute decision to exclusively write in Kurdish. He also tells me about his private experience: "As you are aware, in a country known as Syria, writing in Kurdish was absolutely restricted and prohibited. There were no schools, institutes, or universities that taught it or permitted it. Therefore, writing in Kurdish was deemed a crime punishable by the severest penalties! This means, in other words, that carrying a newspaper or a book in Kurdish could expose its possessor to real danger, whether through arrest, imprisonment, or any type of violation that may or may not cross one's mind. Therefore, anyone who committed writing in the Kurdish language was as if he had committed the crime of murder or unforgivable treason. (Of course, the ban officially persists on the Kurdish language, but with certain distinctions due to the altered conditions in Syria at large.). Consequently, most Kurdish writers turned to writing in Arabic, including myself, you, and many others. The profound impact was felt by those writers and poets, “the tremendous few”, who wrote in Kurdish secretly and covertly, persisting in writing it despite all the harsh, difficult, and exceptional circumstances that could lead them to an uncertain fate!"

Here in Europe, I learned to write Kurdish and gradually began composing in it alongside Arabic. Regrettably, the publication of my books in Kurdish faced considerable delays for various reasons, including challenges related to communication and publishing. The spread and prevalence of my Arabic writing over my Kurdish works resulted from the relatively more accessible and available opportunities for Arabic publication. Additionally, due to the catastrophic and exceptional circumstances endured by the Kurdish people in every aspect of life, numerous external elements have continued to exert influence over Kurdish life, superimposing their will upon it without its own volition. Since the occupation of my city, our shared city, Afrin, I made the decision to write exclusively in Kurdish —a single language for expression, creativity, continuity, existence, and the very act of breathing.

Consequently, my experience of writing and creating in Kurdish has been profound, enriching, and pivotal, at least for me. It roused me from a state of dormancy and slumber in Arabic, even if that transformation was partial, rescuing me from feelings of anxiety, bewilderment, disorientation, and detachment that used to overwhelm me due to the predominance of my literary existence in Arabic, at the expense of my existence in my mother tongue. Writing in Kurdish fostered a greater sense of equilibrium and reconciliation with myself, drawing me back to my authentic essence with more intensity and depth.

Conclusion

The exploration of the languages, apart from Kurdish, employed by Kurdish writers, as well as the act of writing in the Kurdish language itself, demands extensive research and inquiry. This is particularly crucial due to the numerous and innumerable names and paradigms, each constituting a unique case within the creative scene. Perhaps this attempt marks the beginning of an extensive research initiative that gives many voices the opportunity to articulate their distinct experiences and perspectives.

Footnotes:

Halim Youssef: A Syrian Kurdish novelist currently residing in Germany. He has published a number of works in both Arabic and Kurdish, including collections of short stories such as "The Pregnant Man" and "Women of the Upper Floors." He has also authored novels in both languages, including "Sobarto," "Fear Without Teeth," "When Fish Thirst," and "The Beast Within Me." Additionally, he has works published works exclusively in Kurdish, including "The Sleepless Dead," "Water without Adornment," "Auslander Bey," and "Ninety-Nine Scattered Beads," translated into Arabic by Joan Titir and published in German.

Redi Masho: A Kurdish Syrian writer, novelist, and musician currently residing in Qamishli, Syria. He has published two novels in Arabic: "Habokar - The Curse of Al-Ma'arri."

Haitham Hussein: A Kurdish Syrian novelist and writer based in Britain. He has published numerous novels, including "Aram, the Descendant of Stubborn Pain," "The Horror Needle," "A Noxious Weed in Paradise," and "Maybe No One Will Remain," translated into English. He also wrote “Hostages of Sin”, which was translated into Czech and Kurdish. Additionally, He has made significant contributions to novel criticism, producing works such as "The Novel between Concealment and Revelation," "The Novel and Life," "The Novelist Beats the Drums of War," "The Novelist Character”, “The Probe of Revelation and the Depature."

Hussein Habash: A Kurdish Syrian poet based in Germany. He has published in Arabic "Drowned in Roses," "Escaping Across Evros River," "Higher than Desire and Sweeter than a Gazelle's Flank," "Wanderings to by Salim Barakat," and "A Flying Angel: Texts about Syrian Children” and Dead People Disputing in Halls." He has also published in Kurdish: “Quince fever," "Drunk Trees and the Weariness of a Tired Statue."