“Radio Fresh: A Syrian History” is part of the “Meglio di un romanzo” series, curated by journalist and co-director of Q Code Magazine Christian Elia for the Festivaletteratura in Mantua. Originally published by Festivaletteratura and Q Code Magazine, this revised and translated version now appears on SyriaUntold.

The story I would like to tell you begins in the governorate of Idlib, where “every family has a small plot of land planted with olive, fig, pomegranate and berry trees, surrounded by cypresses”. And “many evenings and every weekend” they will gather there to take care of and enjoy it in the company of friends and family. I wanted this to be your first postcard from Idlib.

A snapshot taken by Zaina Erhaim, an award-winning Syrian journalist, who was born and raised in this area and knows it better than anyone else:

During most of my life, my hometown was so neglected that the only national festival that celebrated it was named “the Forgotten Cities.” Suddenly it became so famous that the president of the United States tweeted about it, even spelling its name correctly. Two Nato members almost clashed over it. The UN Security Council convened to address its crisis. It was trending worldwide when Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the previous leader of Isis, was assassinated in the province, and when more than 30 Turkish soldiers were killed on its soil earlier this year.

I was trying, with some Idlibi friends, to understand how our home had been transformed from an overlooked and hidden place, where we used to take pictures with the few tourists visiting us to keep as souvenirs, into one that was being attacked and bombed by people holding so many nationalities and from so many different countries. How famous we had become!

My dear Idlib, how I wish for you to go back to being forgotten and ours again. Until then, we’ll always have your accent in our word, your olive oil in our cells, your trees etched in our memories. And most importantly, wlad al-balad to count on wherever we go.

Today, Idlib is best known because its name is associated with that of the president of Syria Ahmed al-Sharaa, formerly known as Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, head of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

In those early days of last December, Yasmin, a friend, had sent me a message expressing her desire to return to Damascus, calling them “happy and important times”. The same sentiment is expressed by Zaina Erhaim in her article of December 11:

On Sunday at 3 a.m. my mother woke me with a shaky voice. All our phones were ringing, and the TV was loud. “He fell, Zaina. He fell. Assad fell.” At my mother’s words, the thick, protective walls I had been living with for years collapsed under the weight of a flood of new ideas, led by one: I can go back.

On December 8, the feeling of joy was overwhelming. Social media buzzed with real-time updates as people shared their happiness, hopes and concerns. News broadcasts once again turned their focus to Syria, a spotlight not seen since 2023. I called my friends Rania and Munira to express my support. Less than twenty-four hours earlier, I had been in Milan, meeting Christian Elia, the editor of works developed over recent years for Meglio di un Romanzo (Better than a Novel) at the Mantova Literature Festival. As we sat at the Central Market in the station discussing this project on Radio Fresh, we both sensed that Damascus would soon capitulate. Yet, we never imagined that by the next morning — with the echoes of our conversation still fresh — we would be writing to one another to celebrate the fall of Assad.

Raed Fares

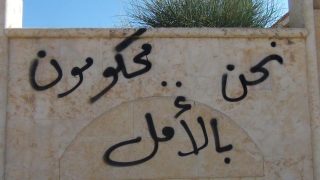

In the article Carrying Home Within, Zaina Erhaim describes how Idlib changed in 2011, when the Syrian revolution started. There was an unusual sense of camaraderie and love: that kind of love for which a person would get arrested or shot on behalf of someone they don’t know. Moreover, there was widespread participation and spirit of initiative from both civil society and activists. Among them was Raed Fares, who began to dedicate himself to documenting what was happening in the town of Kafr Nabl. Here, activists mobilized as best they could: some organized demonstrations (including Raed) and, to do so safely, moved to the countryside around Jabla, others tried to spread information and awareness through pro-freedom slogans hastily left on the city’s walls, and still others through drawings and comics, including Ahmad Jalal, who later on, together with Fares, founded the press office of the media centre and continued to work closely with together even after the establishment of Radio Fresh.

Starting with the Local Coordination Committees (Lcc), self-organization in the country was growing in a structured manner in anticipation of subsequent mobilizations. Military desertion was intensifying, with many of the deserters later going on to form the Free Syrian Army (FSA).

The first Friday demonstration in Kafr Nabl took place on April 1st 2011. According to Raed Fares, the purpose was to raise awareness of the massacres in Daraa.

The newly-formed citizen journalists and photographers, including Raed Fares, documented this event and sent their audio-visual materials to various news outlets, including Al-Jazeera.

One of these videos, through indirect channels, even ended up being broadcast by Addounia TV. Given the lack of banners, the Syrian private channel declared that the demonstration was not Syrian, that it was an external protest.

It was this distortion of information that gave rise to the idea of the Kafr Nabl banners, which made the town later down the line one of the symbols of the Revolution for freedom and dignity.

In the words of Raed Fares:

We understood from the very first weeks of the revolution that the media are at the heart of our battle with the regime, so we had to find something attractive enough for the world to notice our demonstrations, so we thought about these posters, which we wrote in Arabic, English, and even Russian and Chinese.

From this moment on, almost every demonstration would have flags and banners with the date, place, and reason for it. The following video highlights this concept through a song (from 1:00 to 1:50):

Addounia TV is a manipulator, you’re a liar, we don’t want you.

You’re famous for stupidity!

You’re last Friday Bashar!

You’re last Friday Bashar!

Here we have Al Jazeera, a reputation so sweet.

There is none like it in the land.

You’re last Friday Bashar!

You’re last Friday Bashar!

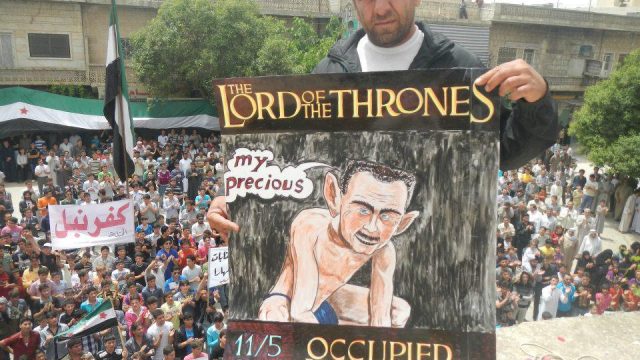

From time to time, Raed Fares and Ahmad Jalal also began to prepare caricatures.

These became a trademark of Kafr Nabl, so much so that the Friday mobilizations became so widely recognized across Syria that anticipation grew week after week. While Fridays already held a high importance, they increasingly acquired new significance as moments of political expression. However, the activists responsible for these demonstrations faced mounting pressure: slogans had to be drafted and translated, spelling reviewed, and the final phrases meticulously rewritten by the calligrapher.

Another source of stress, Erham says, was the security factor: the possibility of becoming victims of bombings and not being able to guarantee the safety of participants; as journalists, the possibility of being accused of co-responsibility by some protesters.

Raed didn’t sleep or eat the night before, subsisting on cigarettes and coffee. “You know, Zaina, if the al-’arsa [Bashar al-Assad] is going to bomb the demonstrators today, I wish I will be among the dead bodies. Otherwise, the people will eat me alive.”

To support each other as much as possible during these times of great responsibility and stress, several groups were formed, including the Kafr Nabl Coordination Committee – which Raed Fares participated in setting up – and the Media Center, which would later merge in 2012 into the Union of Revolutionary Bureaus (URB).

This, in turn, gave rise to the establishment of Radio Fresh the following year.

Raed Fares, Ahmad Jalal, Hammoud Jounaid, and Khaled al Essa contributed to its founding. The URB’s National Organization of Civil Society grouped together various organizations such as al-Mantara Magazine, Maraya Center for Women, Children’s Office, Women’s Office, Labor Office, Aish Campaign and including Radio Fresh. Their task was to execute projects with different activities, from empowering community members, to women’s emancipation, media training, education, medical services, vocational training, cultural programs, and narratives against extremism. The URB managed to employ 670 people in this way.

Zaina Erhaim had the opportunity to visit the centre and writes:

I spent a couple of days at their media office with them. It was a fascinating beehive, men coming in and out all the time, local and international journalists using it as a hub, madafa (guesthouse), hostel and restaurant all at once. They were covering all these expenses of their guests and refused to receive even a penny or a meal from the visitors. To be able to pay for one dinner, I had to go to the souk on my own to buy the food and they accused me of ruining their reputation.

They were working more than 20 hours a day, their eyes always puffy and red, working in shifts so one team member would always be on standby if called to film a bombing or an attack or to offer any other kind of help.

In 2012, in Kafr Nabl clashes between the regime and opposition militias, which had intensified in June, continued. Having extensive control over the governorate, the regime interrupted essential supplies, thus causing significant instability, which was further exacerbated by the collapse of the Syrian pound. Nevertheless, the Kafr Nabl activists continued to carry out their projects, organizing demonstrations from Jabla, displaying their banners on the streets, and uploading their graphics to the Web. All this was done with greater difficulty than in the previous year due to the new conditions and complicated by the fact that the regime’s army was making its first raids into URB journalists’ offices.

Ahmad Jalal: 'Peaceful protests ail but do not die'

25 February 2019

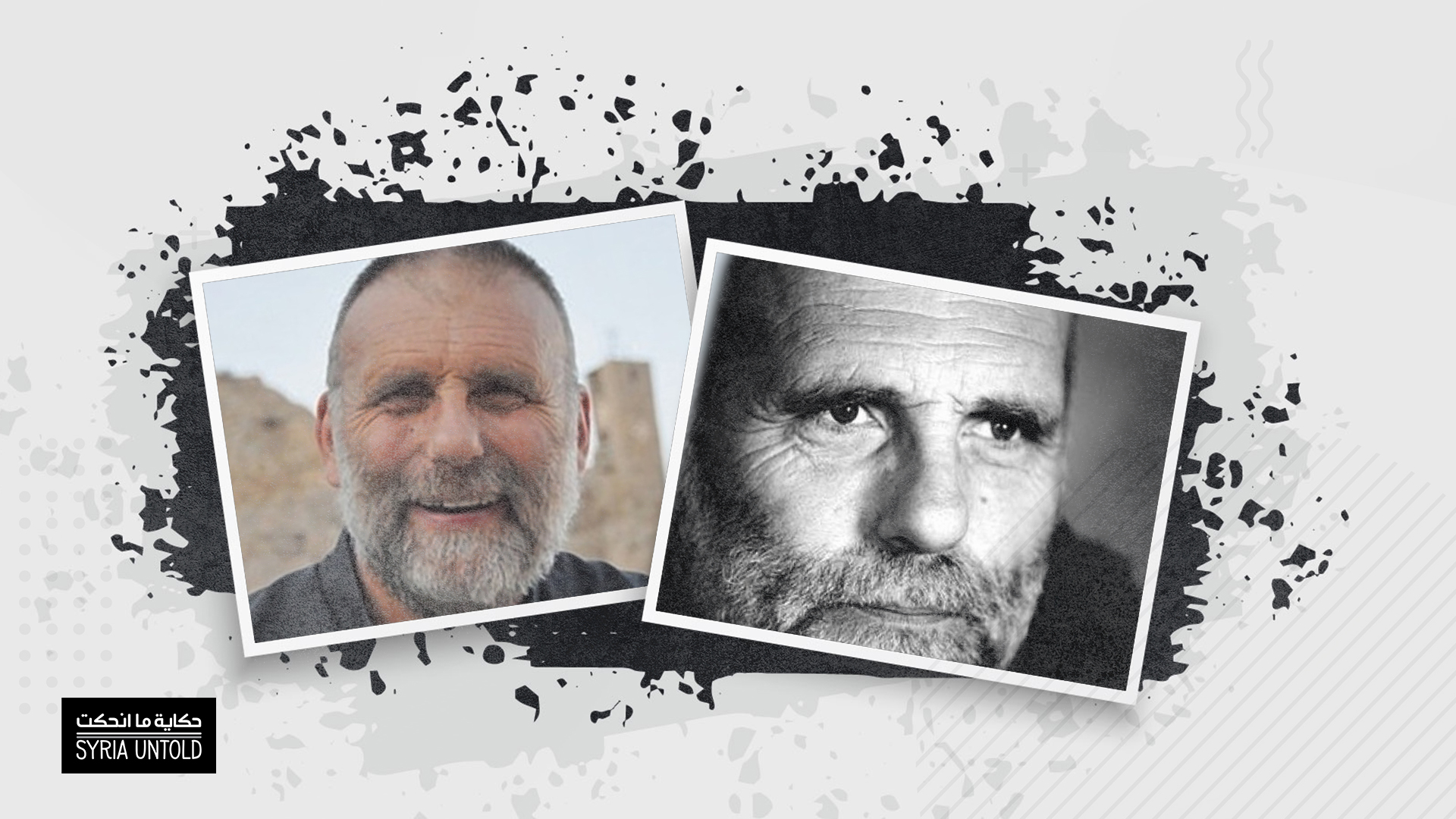

The other co-founders: Hammoud Jounin and Khaled al Essa

In a Facebook post by Raed Fares dated April 6, 2012, there is a man sitting cross-legged, smiling at the photographer.

The man in the photograph is Hammoud Jounin, described by Raed Fares as “our great revolutionary hero”. Like him, Khaled al Essa was also a friend and colleague of Raed Fares, and they were both photographers. Hammoud Jounin had gained international fame as “the barrel photographer”, referring to barrel bombs.

While Khaled al Essa had dedicated himself to reporting on events in the Idlib region and the city of Aleppo, often collaborating with journalist Hadi Al Abdullah. The latter, in turn, had called Khaled “a hero” in an Instagram post on June 24, 2022: “his eyes, full of confidence in the revolution, have crossed the most dangerous places to convey to the world the pain and achievements of the Syrians”.

Raed Fares, on the other hand, presented himself as a media and civil society activist and later as the manager of Radio Fresh. Born in 1972 in Kafr Nabl, he came from a conservative family that had gained certain advantages under the regime, but, as explained by the Italian-Syrian journalist Fouad Roueiha: “During his life, he made a choice to which he remained faithful until the end, and paid the consequences.” Initially a medical student, he left university to work in the real estate sector. For Zaina Erhaim, Raed Fares was a friend. In one of her articles, Zaina Erhaim recalls the first interview she had with him:

I did the interview via Skype, as I was in London then finishing my master’s degree. “Dragon mouth fire” was the username of Raed’s account, which confused me. Why would the intelligent mature mind behind those messages choose such a childish handle?

His status, though, was “I have a dream”.

When the time came to publish her article, Raed Fares made a request to Zaina Erhaim, who wrote:

Raed wanted to use his real name in my article, while the vast majority of the Syrian activists then were using noms-de-guerre, fearing reprisals by the regime. I was hesitant to do so, but he told me: “Since April this year, I participated in the uprising with my uncovered face, full name, posters and even my coffin [protesters held them to indicate that they were ready to die for the cause], and that resulted in being forced to leave my home and family behind to live in a tent in the mountains with al-ahrar [free people] who share the same dreams.”

I put his name in the piece and ended my article with his quote, “Our fear of death and the regime have faded out, our spirits are as high as the sky, and we’ll win soon.”