This essay was first published in Arabic here.

My preoccupation with memory and the world of archives in the past few years has made me alert to, or perhaps obsessed with, the way memory works and how it is constructed and (re-)produced. How unfair it is to reduce memory to a closed-off past that is independent in and for itself, as though it were a sentence that ends, with all the deprivation in the world, with a full stop, which is my body in the present. Could the body be merely a point in the sea of the sentence? Or is it, just as I imagine it, that perceptual distance between all the points, and fields of tangency between the sentence as a material gathering of words and the meaning that transcends them?

The imaginary of the present is the alphabet of both the past’s memory, and the prophecy of the future’s. I imagine myself, for instance, a story crossing the bounds of time and living through the nowness of the body and imagination.

My body is one of its numerous material manifestations, and my imagination is an attempt to take the reins, even if for a while. Oftentimes, I have been unable to distinguish between memory and imagination amid these mazes of deconstruction and reconstruction, and of questioning the meaning of this story in particular. Is the body a renewed material manifestation of an imaginative memory, or of a memorative imagination?

I remember that, at some point during the early months of 2020, which has gone by but left the remnants of a viral enemy—the coronavirus—with all its horrors, chapters and ghosts casting their shadow over our conversations and daily lives, I went too far in contemplating the human collective memory about loss, threats, trauma and pain; a memory under construction that is only just being born.

A Syrian visiting a Nazi camp

25 September 2019

Murder, and the burden of proof

06 January 2021

I then wondered about the real definition of collectivizing in our memory, which some claim has the ability to unite the world and create new awareness of justice and solidarity, and dispel differences between people. Is the existence of a common threat enough to create a collective human “us,” with only our bodies acting as a compass to realize it? This “us,” however, is cut off by our different stances towards the system, along with our intuitions, prerogatives and unfairly distributed rights.

I asked myself another question: Why didn’t these same bodies (our bodies) that have acted as a compass help us before to obtain the rights of the different and weaker others; their rights to be and to achieve themselves justly?

The suffocating state of emergency menacing the country and restraining the human body is only a continuation of the situation that the vulnerable and persecuted communities among us have experienced based on their gender, sexuality and physical or psychological traits. It is only a perpetuation of the hardships these groups struggled with in the old days, which we bitterly long for today.

Imagination and body in face of the pandemic

I remember how I would watch people’s state of panic and savage instinct for survival—or one could describe it as monopolization of survival—in March 2020, in the wake of the total lockdown. Public life was put completely on hold in Germany. I would observe the alienation of people’s memories and imagination, which were capable of coping with daily life and accepting the supposed immunity of a crisis-free Germany. This view made it difficult for people, in the beginning, to give up their routines of comfort and well-being and the rights they took as given. By invoking these days, I now realize that I really was not like them, and I am discovering more and more why I wasn’t.

It was a visible, tangible and audible pandemic, but oftentimes only for its victims. It had an intersectional, participatory, streamlined and multi-faceted essence. A pandemic that traversed the body, language, laws, daily events, institutions and generations. It was racism, a pandemic dragging across eras.

Unlike those around me who felt shocked and forced into isolation, I considered myself lucky because I voluntarily chose isolation a few weeks into the new year of 2020, before the pandemic took the life of its first victim. Yes, I had chosen my isolation. But what kind of choice had I been given in the first place? Another kind of pain had gripped my body and delighted in taking hold of it slowly. It was the pain borne by a rampant pandemic that was no less global. It was a type of selective pandemic, unlike its fellow viral one, and it did not see all humans as equal. It was a visible, tangible and audible pandemic, but oftentimes only for its victims. It had an intersectional, participatory, streamlined and multi-faceted essence. A pandemic that traversed the body, language, laws, daily events, institutions and generations. It was racism, a pandemic dragging across eras.

I remember the unique pain I felt when encountering one of this pandemic’s faces at my workplace, dressed as it was in privileged white masculinity, carefully concealed and coupled with academic structural racism and hierarchical and elitist white supremacy. That pandemic was deep-rooted to the extent that this academic structure served as a reference for knowledge production on the topics of “repressed memory,” “exposing the hegemony and structure of cognitive colonialism” or the “Global South as a theoretical and cognitive producer.” At the same time, it constituted a means to reproduce white supremacist and post-colonial structures.

The uniqueness of the pain resulting from the racist experience I lived lies in its smooth inhabiting of my body. My personal, familial and shared memory, just like that of many other people, is rife with stories and experiences of racism in Germany ever since my family was granted political asylum in 2006. At the time, my abode was not my house and private space. Rather, it was my body, and it was at the complete mercy of pain, an enemy invading it internally, a separating yet connecting distance. I was not concerned much with what was going on outside, because here I was, on the inside, captive to a body that was merely a material metaphor or summoning of previous bodies that perished due to the pain of loss, racism and tyranny. I assiduously buried these bodies in the folds of my memory, whose only lifeboat was oblivion. It was a boat that took me back to where my material metaphor awaited me on the banks of the present.

In light of my recent experience of racism, I discovered that my boat was an illusion vanishing by prescription. By anchoring it, I was actually weakening it, and by proving it, I was actually disproving it. The more I steered that boat towards the desired shore of forgetfulness, the more I yearned for the memory, and the further it drifted away.

The hope of forgetting does not entrench the actual memory, rather the sensual memory of the body filled with rage, pain, suffocation, numbness, heartbreak, trembling and brokenness. This experience awakened the ghosts of the sensual memory of my body. It also stirred previous experiences I thought, or perhaps hoped, I had forgotten for good.

Our bodies are subject to different political, economic, social, sensual and memory forces. In Germany, I am now living under the state of emergency law, just like fellow citizens, and I am experiencing daily the difference between myself and others in the worlds of the imaginable.

When thousands of German people took to the streets to condemn the government’s restriction of the freedom of movement and public and private life, their imagination could not fathom the government’s direct and close control of their movement, bodies and natural, given rights.

For me, the situation was not only imaginable, but also normal. It did not shock the tools and elements of my memory and imagination. That memory carried in its corners the experience of asylum centers or the political detention of members of my family and homeland. Granted, the state would control the movement of your body and limit your freedom. Granted, it would assign to you an arbitrary number reflecting the kilometers of the surface area you have no right to trespass. You had absolutely no freedom because you were a refugee, and you were the weakest. You had escaped your weakness facing the tyrannical regimes in your homeland which controlled your body, country, history and future.

We communicate through this obedience, like a collective code in the public sphere. Its language is voiced by our distant bodies, mask-covered mouths and our fear of each other as though we were all suspects by default.

Like the shadow of a monster in my memory and imagination, I could not escape recalling the practical sense of the state of emergency law in its Syrian Assad version. There, fear, threats, oppression, arbitrary quarantining and forced family distancing were a given, while enjoying personal and civil freedoms was not. I imagine them today—the asylum centers and political prisons and the former extermination camps—like an institutionalization of the state of emergency, where the bodies become historical landmarks and archives of pain, deprivation, savageness and injustice.

Our imaginations, memories and given rights vary in the face of the pandemic. But one feeling unites us: the feeling that we are outside history, drowning in the current moment where time has turned into a place we know we exist in somehow. We are stuck in the now, sharing the worlds of the un-imaginable this time, and we are standing naked and innocent in an extreme, existential relationship of subjugation to the government, and we have to listen and obey. We communicate through this obedience, like a collective code in the public sphere. Its language is voiced by our distant bodies, mask-covered mouths and our fear of each other as though we were all suspects by default.

In search of the best picture in the world

22 January 2021

Alienation, and an embrace

After the passage of some time I could not really estimate, as the sense of time disappeared in the present moment of quarantining at home, I decided, rather daringly, to meet up with my Italian friend who also lives in Berlin. I missed her like someone who has never felt longing before, as if it was my first time yearning for someone. It was my first encounter with someone outside my isolation in a while.

We snuck away from the ever-unfolding status quo, grateful to the consoling sunshine of that day. We picked a park halfway between our houses. The purpose was not a fun outing, but an attempt to snatch parts of our bodies from the stillness of the quarantine, even if for a moment or the blink of an eye, to escape the reality of social distancing.

The desired moment of meeting, which I so longed for, came. The conflicting feelings of solace and deprivation best described my emotional state. Deprivation crowned my state of being and was further entrenched by the language of greeting, as its alienation and my confusion at the time resembled the alienation of my mother tongue when I reached Germany.

Neither of us knew that, one day, we would have to force our bodies not to embrace. Grudgingly and with deep confusion, we contended with that estranged greeting and made our way to the park. We exchanged words and gazes like mute people speaking for the first time, like the blind seeing for the first time.

Overwhelmed by a sea of delayed words and tears that we could not wait to empty from our alienated souls, we sat on the grass. Pain was a road to our souls—a road paved with tears or one traversing our bodies. On that road, we drowned in spirals of conversation about what was happening around us and about the situation in her home country. The pandemic infesting the world was draining the bodies, souls and hearts of people back home. We talked about Berlin’s effect on us. And, we cried…Oh how we cried!

Each stare in her beautiful, crystal eyes made my heart and body ache. My body begged me to hold her tight, as it had always done and loved. I felt my body retracing its memory and mastering its language, thus pushing me towards embracing her. However, confused and against my will, I pulled away, not out of a masochist pleasure, but out of fear for her from unintended harm by the same body that longed for her. At that moment, I felt a strange contraction in my body, and in the midst of that longing, I realized the meaning of an embrace. I also recognized the memory of my body during its alienation. But, that would not be the first time I experienced alienation in an embrace.

My mother, my little brother Mehyar and I would repeat Fairouz’s song "Sallimli Aalei" (“Send my Regards to Him”) during an endless, tiring and dusty journey from the Syria’s al-Jazira region, the only place I lived in Syria, to Damascus. Our purpose was not to visit the capital itself; we had another destination. Calling it a destination is too respectful. It was, in fact, an underground dungeon, otherwise known as Adra prison. My father was detained there for long years on charges of “carving out Syrian territories and annexing them to a foreign state” and “sparking sectarian tensions.” In other words, he was convicted of being a Kurdish political opponent of the regime.

We did not repeat Fairouz’s song for the sake of it, but to please my insistent six-year-old brother who wanted to surprise my father and sing it to him when we met. Mehyar was aware only of that wish, which pushed him to struggle with the lyrics of the song the whole way happily and amusingly. Unlike me, he had no idea what the visit meant or where it was.

Iron bars stretched upwards to the ceiling, before piercing through my shoulders and into my head. To the left, a flat-faced man stood wearing a military uniform with a rifle around his waist.

We reached Damascus, the city of jasmine. No matter how hard I tried to imagine the famous aroma of its jasmine flowers, that omnipresent smell in my nose, though forever absent from my language, would stand in the way. It was the smell that welcomed us in the city of jasmine, when it revealed the ugliest face of my country, the prison. I remember feeling a general numbness due to the sadness that masked my mother’s facial features, or perhaps it was that smell or the horror of seeing the many sullen, broken faces when I entered Adra prison.

We sat in the waiting hall, along with other visitors. A wall that was almost shoulder height, at the time dividing one-third of the hall. Iron bars stretched upwards to the ceiling, before piercing through my shoulders and into my head. To the left, a flat-faced man stood wearing a military uniform with a rifle around his waist. The three of us waited, in silence and shock, for my father to come out of the door behind the iron bars to the left, over there, directly behind the police officer.

Then, there he was, like the sun lighting up the darkness of our waiting and silence. We rushed towards the wall to be near him. The closer we got, the deeper the yearning. The deafening silence was the most eloquent expression of that yearning. In that silence brewed the loudness of the pain. I only remember from that encounter my father’s eyes, where I wished to remain prisoner, and the silence in between those walls—a silence broken by the voice of Mehyar who suddenly complained about his inability to see my father behind the wall that separated our family. My mother carried him in her arms in a way that allowed him to lean on the skirting board.

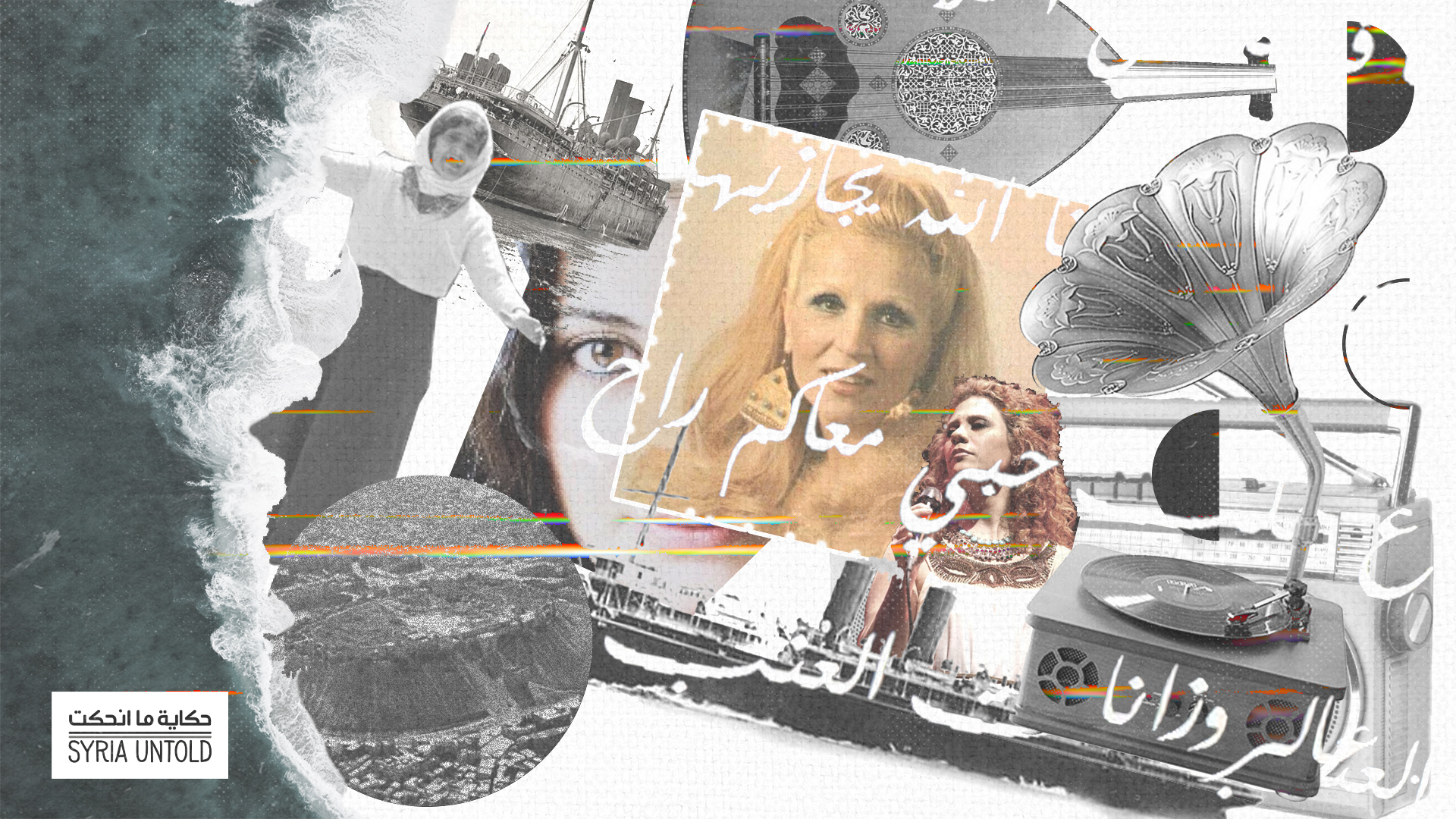

A famine, a ship and a folk song that spanned borders

18 December 2020

Sudan: no longer a visa-free haven for Syrians

15 January 2021

My father smiled. It was the loveliest smile in the world, and it radiated across that place and brightened it. Mehyar wanted to seize his golden opportunity to make his wish come true by singing to my father. Time stood still, and nothing else existed, except our locked gazes that were enough to melt these bars. Mehyar’s accompanying voice resounded in the void of existence:

“This is my lover who whispers my name,

He has worked hard on his studied silent game,

It is clear what ails him,

Do not ask what ails him,

Pretend you don’t know,

Tease him by not teasing him,

Pass my regards to him and give him my best,

Kiss his wide open eyes for me,

Kiss his cheeks and linger there for a while,

Do you understand me? And, pass my regards to him…”

Songs, voices and lyrics were never a real extension and a caring embrace for absent bodies, which were themselves transformed into prison cells. We felt alienated and deprived of an embrace, which rendered our bodies and memories grief-stricken and estranged.

In his book Corpus, philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy wrote that the body must be a stranger to one’s self before it can become one’s own. Jacques Derrida, a pioneer in the deconstruction theory, described the act of embrace as a space in which the self touches the other, who is the self at the same time. Touching the other’s spirit touches one’s own as well. One cannot realize the threshold of oneself except by transcending it, alienating it and altering it. Did I really lose my body or did I re-appropriate it by alienating it, or were the lyrics of Sallimli Aalei, and the subsequent gaze, silence and writing my refuge?

Body of the text, text of the body

After meeting my friend, I returned to my abode. I felt my body was muffled from the inside. Strangely, the first thing I wanted to do—after washing my hands—was write. The urge to write thrust out of me in an unprecedented way; it had been blocked for a while before that encounter. I wanted to write to my friend and about her, and to myself and about myself. It was as though language was a body closer to me than my captive body and its muffled voice.

Jean-Luc Nancy liberated the notion of the body from the chains of the duality of the physical body and soul, of interiority and exteriority, and transported us from the randomness of writing from or about the body to “body-writing” or “exscription.”

Through its alienation, the body disintegrates and deconstructs its own writings, from experiences, meanings, habits, significances, symbolisms, memories and history, to rewrite itself unencumbered. Nancy believed that the exscription of the body was a process not only meaning life and death, but also of each real bodily event touching its sense. Writing, then, is a bodily event. The body is a textual structure and writing per se, or as Nancy puts it, is “the architecture of sense.”

After exscripting my body that day, I figured out the meaning of writing and language in my memory, which had always been a body free from all bars. I recalled the letters to my father in prison, only a few of which reached him, and my hysterical writing during my first years in Germany, which were not aimed at poetry, prose or text, but were merely writing for the sake of writing.

It was as though language was a body closer to me than my captive body and its muffled voice.

We are experiencing now a more focused and new analysis and representation of our bodies, not just through language and writing, but also digitally. The restrictions on our movement have forced us to rely on other ways to communicate through stone walls, time and body. Consequently, our bodies have seized the opportunity to experience their sensual and cognitive selves in a wider, multimedia space with symbolic, textual and visual gateways.

We experience our bodies as an expansive spectral space in which sensory, imaginary, cognitive and memory worlds touch and overlap. They are not mere containers and places that are bound to be filled and are susceptible to captivity or isolation. They are infinitely open temples of existence that never cease to expand and intertwine. I realized this, when I saw myself as a refugee seeking physical experiences and new embraces and craving a sort of connection with my other self and with myself—a textual and digital connection I experienced with my body.

Body of the future

The uniqueness of this temporality in which we live does not only lie in the stubbornness of our bodies and our imaginations in the present, as if we fell into a gap between the past and the future. It also lies in the fact that it put us in daily contact and under direct reminder of our limitations and our mortality on the one hand, and of a new beginning, on the other.

I wonder about the obscure future: Will digital life based on texts, images and symbols, along with textual life, make us more aware and alert to our gestures, touches, gazes and bodies in their physical present after the emergency vanishes?

Will this experience allow us, despite our different privileges and resources, to perceive new collective ways of remembering and seeing our relationship with the self and the other? What is the nature of this future in which human beings will carry memories of loss and deprivation of their power, relative as it may be, over their threatened and threatening bodies, in their complete existential submission to the power of chance, the sense of responsibility and the imperativeness of authority?

If the beginning, as Plato says, is “a god who preserves and rescues all things, as long as he is among the people,” then could this god, accompanied by this memory and these new perceptions, make a new perceptual and political awareness possible? What will happen when we overcome this viral pandemic? Will we really return to the past that we parted with?