This dialogue is part of SyriaUntold's series on Syrian theater. Read this piece in its original Arabic here.

Since the outbreak of the Syrian revolution and its disintegration into a grinding war that displaced millions of people, Syrian artists have taken on the role of historians, reporters and storytellers. They are trying to answer the question: “What really happened in Syria?”

This effort gave rise to new issues in Syrian artistic practices that went beyond their national borders. Artists became responsible for narrating their country’s destruction and its people’s dispersal, in the hopes of preserving a memory threatened with extinction.

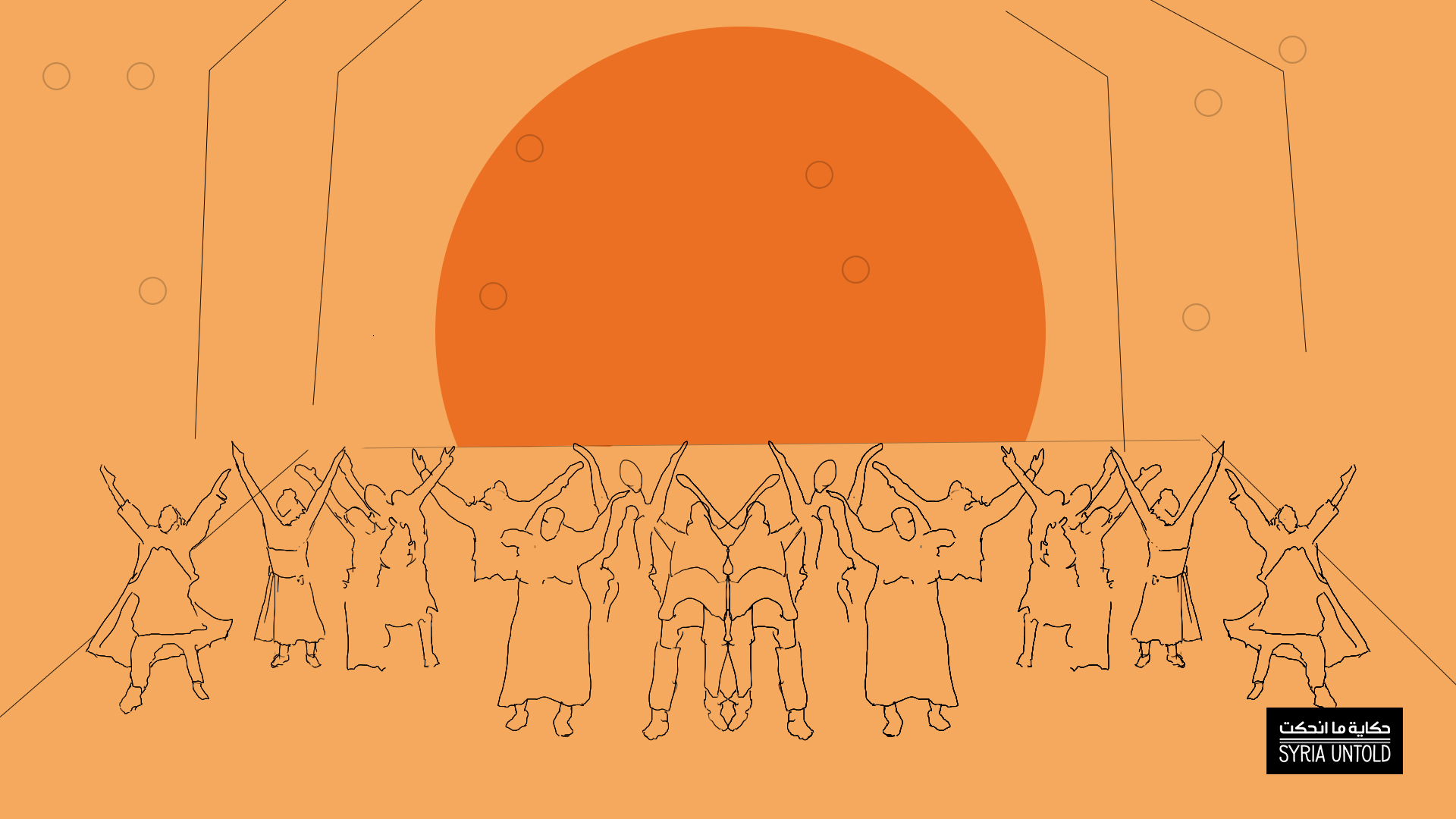

In this vein, theater has become one of the main platforms through which the Syrian story is told, albeit from afar. A generation of theater makers transferred their work from Damascus to Beirut, and from there to Berlin or Paris and other lands of refuge. It is a generation that entered adulthood amid war and diaspora. Dozens of plays were written in an attempt to chronicle the Syrian plight and reveal the truth, by drawing on facts and events that coincided with and sometimes preceded the developments of 2011. For example, I Can’t Remember by Wael Ali (2014) questions the memory of a former detainee who moved to France in 1999. There is also The Confession by Wael Kadour, which was produced and released in 2018, after going through a long stage of development that began in 2013. The play tackles events that took place just before the revolution.

Some of these works were produced in Arabic, and in the Syrian colloquial in particular, across several Arab and European capitals. Some of them appeared at a handful of the most important international venues and festivals, such as the works of playwright Mohammed Al-Attar and director Omar Abu Saada, or Liwa Yazji’s Goats (2017), which was supported and produced by the Royal Court Theatre in London.

Solidarity with the cause

Although a group of Syrian plays emerged and traveled the world in the last few years, the fact remains that it was challenging to produce and promote a large number of these texts, as they remained confined to spaces whose primary goal is to support refugees and discuss the issue of exile. In such spaces, this political and administrative framework turned into a pivotal theme dominating the artistic process and the stories that artists sought to narrate. We witnessed the production of many small plays whose producers were primarily looking to entrench their solidarity with the Syrian cause and their desire to contribute to the integration of Syrian artists into their new work environments.

Syrian theater through a decade of war

01 June 2021

Walking a tightrope: Syrian theater in Germany

21 June 2021

Despite the good intentions, such initiatives led to isolating part of the contemporary Syrian theatrical production (among other artistic productions coming from regions undergoing conflict and war) from the history of theater and contemporary art, limiting it to the framework of social and political activity. At the same time, we have seen a growing academic interest in this theatrical and artistic production, not only as a quasi-anthropological body of work that allows the reading and understanding of history as it unfolds; but also as part of a growing interest in the current Arab artistic and cultural practices as they allow people to reconsider the meaning of contemporaneity from a non-European perspective.

Between the question of history and the question of art, to what extent can one talk today about a Syrian theater that has specific characteristics, contents and writing techniques? Characteristics that allow us to read, criticize and analyze away from any concerns of sensitivity, sympathy, or denial? What are the chances of this output evolving and continuing to exist in a world suffering from an inherited colonialism that seems yet to be resolved?

To answer some of these questions, I interviewed the Syrian writer, director, and cultural expert Abdullah Al-Kafri and the French researcher Simon Dubois, who specializes in the sociology of contemporary Syrian theater. This dialogue has been lightly edited for flow.

Abdullah, you are a Syrian writer, director, and cultural expert. Today, you live in Beirut, where you run Ettijahat-Independent Culture. Based on your work in the theatrical field and your observation of the theater scene both inside and outside Syria over the past decade, what does Syrian theater discuss today and how?

This question requires a deep dive into agreeing on what Syrian theater is, especially after it went through a rich and complicated journey over the past decade. To explore the meanings that can be structured as far as the dramaturgy of the Syrian theater is concerned, I shall first stop at texts, which are the central place where playwrights test the question of theater. It is here that they also try to understand what happened, to be able to retell the story.

In these texts, we witnessed an array of content, most importantly the attempt to formulate reality and present a narration of what happened and is still happening. We witnessed texts whose authors began to initially define them as political productions. The relationship with language has also irreversibly changed, as it started to break free from the restrictions of censorship, to dig deep into the components of Syria by focusing on and dealing with dialects, regions, villages, cities and districts.

The middle class is the one most represented in texts that seek to answer the questions raised amid the current historical transformations: the fate of the family and the political divisions that led to even deeper divisions, the moral choices in the face of Syria’s moment of truth, the confusion over what this class hopes for and the impossibility of continuing to accept previous justifications and compromises. An important point must also be noted, which is the shift from general concepts to personal revolutions, such as rebellions against parents and social values, sexual choices and other subjective and intimate issues.

Syrian artists have taken on the role of historians, reporters and storytellers.

The main aspect of Syrian theater’s dramaturgy is perhaps the attempt to formulate reality in a dispersed manner. Dispersion witnesses the disintegration of the meaning and the need to view and share this disintegration with the world.

Simon, in 2019, you presented your doctoral thesis on Syrian theater in exile, in which you addressed a generation of women and men working in theater by analyzing their paths from Damascus to Berlin or Paris, through Beirut and other transit centers. What do you think are the most important aspects of theater works that are being produced today outside Syria?

I think one of the answers can be found in the fact that Syrian artists are facing a very momentous present that they are still trying to observe and understand. Syrian artists constantly raise the question of the artist’s position in a society that has lost the meaning of unity and harmony. I see that this contemplative dimension is one of the main characteristics of contemporary Syrian dramaturgy, be it through the “I” of the writer, which is actually present on stage, or within the writing techniques themselves, as is the case, for example, with Wael Kadour’s plays. It is also a personal search, as Syrian artists are looking for a place in the various societies that constitute their audiences. The plurality of potential audiences may also be among the characteristics of contemporary Syrian theater.

I personally believe that Syrian playwrights are in a transitional stage that has yet to come to an end. I also believe that research and experimentation are among the characteristics of this theater. We are now facing a historical and geographic transition from a form of theatrical production targeting a local audience that was barely presented outside Syria, to a form of production that went completely beyond its borders. The return of Syrian theater to its previous borders might even become almost impossible.

Current conditions of Syrian theater

28 May 2021

Songs of nostalgia in New York City’s long-lost ‘Little Syria’

05 March 2021

Abdullah, since the departure of most Syrian playwrights from Syria, most Syrian theatrical texts have been written in countries where Arabic is not spoken. In some of these countries, Arabic is even seen by some as problematic. To what extent has the geographical shift, and the linguistic and social displacement, actually affected the development of Syrian theater in recent years?

I think that the question of language in the Syrian text is very complex. Some of this complexity is related to stereotypes in some contexts, including where Arabic is spoken. This is the case in Lebanon, where many Syrian theater makers settled. Other problems are related to the legal and social situation, as in Europe, though more specifically in Germany and France. These are deep issues resulting from the fact that most Syrian artists today address an audience that does not know their language, which may create difficulties in the reception of their works. And if these issues seem primarily technical (trying to follow both the performance and the translation at the same time), the fact remains that they reconstruct the intake process from scratch.

In this vein, it should be noted that language is an option in artistic production and not only a means of communication, as it is both an artistic and political tool. Producing a text about Syria in the Syrian dialect is not the same as producing a text in French or German. An author’s fluency in English, French or German does not necessarily mean moving to writing in this language. Also, the presence of a given language compensates for the geographical loss. With the loss of Syria, language comes as an alternative that tries to transfer Syria from its geographical location to the history of the arts.

On the other hand, Arabic in Europe comes with the burden of its interpretation and reception, and consequently, puts theater producers in an uncomfortable situation. This problem does not concern artists coming from Syria alone, but rather has to do with the question of the world and the “other” in general, as it is the case, for example, of the Belarus Free Theatre. This company adopted English in its work, which forced it to engage in local and international issues and undermined its very foundations.

Artistic production in a foreign language will be an inevitable passage for the development of Syrian theater in the coming years. Damascus 2045, written by Mohammad Al-Attar and directed by Omar Abu Saada in 2019 at the Teatr Powszechny in Warsaw, was performed in Polish and is now part of the theater’s repertoire. This is probably among the first experiences in this context. What is interesting here is that it is a show based on a story that imagines Damascus and the Arab region two decades from now, and this combination of the choice of a foreign language and the futuristic elements, may be corresponding to the choice of Arabic and the present.

Syrian artists are facing a very momentous present that they are still trying to observe and understand

Simon, language and translation are among the main issues that worry Syrian theater makers in non-Arabic speaking countries. Nevertheless, I feel that some of the Syrian plays that are written in Berlin or Paris today, may implicitly address the audience of the Circle Stage at the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts, or the Al-Hamra and Al-Kabbani theaters in Damascus. What is your take on this?

No more than seven years have passed since the generation of playwrights you are referring to settled in Europe. The relationship of this generation, who studied and worked in Syria before 2011, with the issue of language and translation is completely different from the position of the generations that are currently training in Europe, and who will very naturally produce theater in local or multiple languages in the future. It is the responsibility of the first generation to maintain the bond with certain theatrical traditions—albeit in part—and with the audience of Syrian origins; at a time when this generation raises the question of theater and production to an audience that does not necessarily understand their language and story.

Regarding France, there are only a few Syrian playwrights who are fluent enough in French to write in this language. But the condition of French production forces them to consider the issue of language from the very beginning. This is how we noticed the growing importance of language in Syrian theatrical production in France and Europe, be it in terms of the writing or producing language, or as one of the main elements on stage. Translation has even started to accompany writing. Certainly, the entry of French and European producers into these projects from their early stages increasingly turned the attention to the various forms of linguistic preparation that must be taken into account, as the translated text poses questions such as: Where will we display the translation? What is the relationship between the readable text and the actor’s body on stage? More broadly, what is the relationship between translation and scenography? All these questions accompany the question: To whom am I writing?

Emerging Syrian theatrical experience in Europe

14 June 2021

Simon, the question of translation leads me to the question of the growing European academic interest in Syrian art production. What do you think is the reason behind this interest? Do you think that this research effort will contribute to giving Syrian theater more space outside its national borders?

We are certainly witnessing the emergence of a generation of researchers who insist on primarily dealing with Arab theater as a text, performance and artistic document. There is a new awareness that Arab theater has a long history that has not been covered enough in Oriental studies and art history in general. These researchers seek to give Arab and Syrian theater a real position that goes beyond dealing with it as an “imported art,” within a broader context and effort that seeks to establish a non-colonial approach to contemporary Arab theater in Europe and the West.

It is true that the academic world is particularly interested in Syrian and Arab theater productions that followed the events of 2011. This is not only because Syria and the Arab world are heavily present in the media and in the public space, but also because there are a large number of French and European researchers who have an ancient and deep relationship with Syria and the region that made them take a clear position towards the events. Some of them have even played a role in diplomatic mediation, and took it upon themselves to contribute to the integration of Syrian artists in their new climate. These academic circles, part of which are fluent in Arabic, are certainly playing an important role today in terms of translating and conveying Syrian theatrical production to its multiple new audiences.

Abdullah, Syrian art received considerable attention after 2011. However, this interest seems to have somewhat faded, especially with the influx of millions of refugees to Europe—that is, at the moment the problem for the Western audience moved from the lands of conflict to the lands of asylum. Within this intellectual and political climate, which was complicated by the COVID-19 pandemic, what are the prospects for producing and receiving Syrian theater in the coming years?

I think that the prospects for producing and receiving theater coming from Syria are related to the question of theater today and its fate in the world. Arts, and performing arts more specifically, are going through a critical stage. The pandemic, which took attention away from any second cause, has destroyed the idea of gatherings and direct communications, which are part of the essence of performing arts. This will have consequences for years to come. There is no doubt that solidarity and support for performing arts groups must be essential in the coming period.

Most importantly, the methods of support should not be limited to digital platforms, as these question the medium itself and destroy the meaning of “now/here.” I also expect us to witness significant impacts on the use of clean energy and open-space performances that increasingly rely on digital technologies.

And unfortunately, large gatherings will diminish and new performances will witness a slight decline for years to come. But despite it all, there is a chance, albeit slight, to place Syria at the heart of what is happening by creating an approach and narrative about the legitimacy of this country and its arts, and bringing its story into a global context that has tested the fragility of safety nets for a year. This takes place as the country experiences all forms of fragilities for a whole decade, and continues to move from one pandemic to another, and from one forced closure to another.