“Radio Fresh: A Syrian History” is part of the “Meglio di un romanzo” series, curated by journalist and co-director of Q Code Magazine Christian Elia for the Festivaletteratura in Mantua. Originally published by Festivaletteratura and Q Code Magazine, this revised and translated version now appears on SyriaUntold. The first chapter, “A Story that Begins in Idlib”, is available here.

Radio Fresh was founded in Kafr Nabl, Idlib, in 2013. It was a unique radio station, but not the only one. In the same period, many other radio stations were proliferating in the areas under the control of the opposition, including Radio Alwan in Idlib, founded in 2014 by law student Ahmad al-Qadour.

Initially, Radio Fresh did not engage in journalism—the newly established Kafr Nabl Media Center already existed for that—but it served as a sounding board for resistance communications to protect civilians from regime attacks.

Since the early months of 2012, the Idlib countryside had been liberated and passed under the control of opposition forces, ushering in further clashes for the liberation of the entire governorate for the rest of the year.

In early 2013, the Syrian army officially left Kafr Nabl and the rest of the province, with two important implications. First, the regime’s retreat left a power vacuum that would be contested by various actors from the end of 2013, including Daesh. Second, the army increased airstrikes. Since the regime had failed to maintain control of its territory by land, it chose to intensify the air campaign to regain control, and it also decided to do so through the use of barrel bombs: devices consisting of a metal container (usually used for transporting oil), emptied of its contents and filled with explosives, scrap iron, and bolts.

Due to this new circumstance, the so called “Observatories” were born, and there were 17 of them in the Idlib governorate. Their goal was to save as many citizens as possible from the bombings, and to this end they penetrated the regime’s frequencies to learn about and communicate incoming attacks through the use of wireless devices so as to evacuate the population in time.

Helicopter arriving towards the work area; attention… helicopter arriving northeast of Kfarawad; incoming Lattakia helicopter entering Kansafra airspace eastward… attention!

This work was carried out by volunteers who could operate individually or in monitoring teams, positioning themselves on the hills in order to have better reception, sometimes working non-stop.

For Five Days, Sweida’s Soul Was Crushed—Its People, Homes, Crops, and Livestock... and So Was Mine, Trapped in Berlin

04 August 2025

Later, the Observatories began to coordinate also with civil protection teams and hospital doctors, for example for urgent requests to donate blood or to contact the families of anonymous patients who arrived at the hospital during a particularly chaotic moment. Civilians themselves could in turn contact the Observatories in case of need.

Journalism at the service of the community

However, the Observatories also presented some issues. Some operators tended to use populist, sectarian, and incendiary rhetoric. Even more importantly, their communication could not reach the entire population as not everyone owned wireless devices (particularly walkie-talkie). If at the beginning of the revolution these products were readily available in shops at competitive prices, between 15 and 20 dollars, with the outbreak of the war in 2013 their price had risen to 100 dollars each, rapidly eroding families’ purchasing power.

Radio Fresh tried to remedy these problems as much as possible by broadcasting the Observatories’ communications via radio. However, it also encountered some difficulties and struggled to reach everyone’s homes. Just as some families, given inflation, were unable to purchase a wireless device, not everyone had a radio at home.

The constant bombing made it difficult to stabilize an FM signal and also impacted all civil society activities—politics, activism, and information—in which radio members were also involved. Zaina Erhaim documented this in an article she wrote about in 2013:

I photographed the posters in front of the media center as we left, in case I wouldn’t be able to document them during the demonstrations if they were bombed. […] When we reached what became known as Freedom Square, the first mortar shell fell, followed by a couple more from Wadi al-Daif, a nearby military base. Chaos overtook the senses. The dust from the bombed-out buildings blinded me. I ran to the nearest wall, waiting for the raids to end. Fortunately, no one died that day, and the demonstration was cancelled. When I finally found Raed, he was relieved, laughing out loud, proclaiming, “We made it another week!”.

Kafr Nabl, much like the broader region of Idlib, had undergone a transformation. Many citizens had left, and in the meantime, many new families from other Syrian cities had arrived, and the previously existing social fabric had changed. The unemployment rate became higher, feeding one’s family was very difficult, and there were constant blackouts.

Civil Society Spotlight: Episode VI

06 August 2025

However, in the absence of jobs and electric devices, people had more free time, and thus new social habits were generated, made up of social contacts in front of their homes, in mosques, in gardens, or in orchards. The war had forced them to rely more on each other, so much so that they visited each other more often to share the moment they were going through. In times when the Internet was down and communication via social media was impossible, this was the most effective way to circulate information.

It is in this context that, despite the challenges, Radio Fresh FM had managed to reach an above-average audience. Above all, it had been able to understand the needs of its listeners. Over the course of the year, the station gradually began to take on new functions. It began to follow in the footsteps of the Media Center by broadcasting independent news.

Fares said about this phase:

Listeners noticed our reliable coverage, and we quickly became the most popular independent voice, especially in the liberated areas. […]. We also became the main source of on-the-ground information for the international press, which is hesitant to send its journalists to conflict zones like Idlib. If it weren’t for us and other independent voices, terrorists would be the only source of information on Syria locally and internationally.

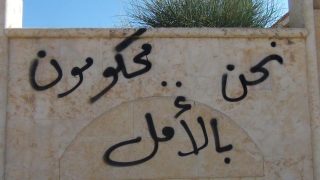

In the same period, the narratives of Jihadi armed groups started to emerge, which added to those of the regime, and both began to play an ideological game to win the soul of the country. In this context, Fares stressed, the work of media such as Radio Fresh was precious.

The radio began also offering educational programs and training courses to more than 2,500 young men and women, helping them become citizen journalists, who were “much needed in Syria”. It also offered more general schooling, educational programs, childcare centres that provided young people with some relief from the war, and discussion spaces for the population to express their thoughts, such as the program Shakawa al-Nas (Complaints from the People), satirical programs, and even various competitions with prizes, such as the program Yamit Masa (Good Evening).

To establish a direct channel with its public, Radio Fresh had installed mailboxes around the city and surrounding villages, which gradually increased in number, reaching around thirty by 2016. The mailboxes were a strategic tool, first and foremost, to allow people to communicate with each other and with the radio when other forms of communication were unavailable. They allowed them to send requests, complaints, topics, stories, and even responses to the Yamit Masa program to the radio.

To carry out all these programs, Radio Fresh began hiring staff, thus becoming a source of income for many men, women, and young journalists. Another goal was to create an environment of gender equality and women’s empowerment by establishing additional centres to teach women skills such as reading, computer skills, first aid, and civic activism. Radio Fresh aimed to raise awareness among the girls in that community, demonstrating that they could achieve their dreams, that they had no additional obligations, and above all, that they represented the future of the country.

The Video Productions

In 2013 a series of events deeply affected the course of the Syrian uprising and the ways activists and citizens, including those of Kafr Nabl, were looking at it. The regime began to use chemical weapons against its own population, which in August 2013 culminated in the attack on Eastern Ghouta that killed over 1500 persons. The hopes of Syrian activists that these actions would finally convince the international community to a military intervention were rapidly frustrated. In the end, the only demand to the Syrian regime was to get rid of its chemical arsenals.

It is in this context that the community of Kafr Nabl produced the short film The Syrian Revolution in 3 Minutes, directed by Raed Fares, organized and performed by ordinary citizens, while the Free Syrian Army (FSA) provided the machine guns. Ahmad Jalal contributed illustrations and Hammoud Jounid played the role of Russia. The short film was aimed at showing solidarity with the victims of the repression but also addressing the Western audiences who seemed unable to comprehend what was happening in Syria..

The film chose to interpret the Syrian context through a universally recognizable scene: the caveman era. It represented a simpler chapter of history, where the prevailing anarchy allowed communication to be direct and clear.

Following this short, Raed Fares confirmed that the crew attempted to produce one every week, an example being A Dialogue Stained with Blood where Hammoud Jounid always stars.

Another example is Support the American Attack, which involved children, women, and elderly men. This second short film had a certain impact, having been screened during a session of the United States Congress and featured on the front page of the New York Times through an interview conducted at the Kafr Nabl information office.