“Radio Fresh: A Syrian History” is part of the “Meglio di un romanzo” series, curated by journalist and co-director of Q Code Magazine Christian Elia for the Festivaletteratura in Mantua. Originally published by Festivaletteratura and Q Code Magazine, this revised and translated version now appears on SyriaUntold.

The first chapter, “A Story that Begins in Idlib”, is available here.

The second chapter, “Citizen journalists despite all”, is available here.

2013 was a turning point. As Ahmad Jalal explained, rampant corruption, both in the regular army and the FSA, and the profound social and economic malaise after two years of war, favoured the rise of radical groups that had already begun expanding in the region for years.

Their public discourse — characterized on the one hand by a strong anti-Western sentiment over its failure to aid the rebels against Assad’s massacres and, on the other hand, by the promise of a more egalitarian distribution of wealth — rapidly gained them popular support.

In 2014, ISIS gradually became the most successful armed Islamist organization in Syria, and soon dominated the media coverage at the international level.

The radicalization and the first murder attempts

During the same period, Kafr Nabl continued to lose residents while welcoming a large influx of displaced people from other areas. Water supply difficulties, inflation of basic goods, and reduced daily electricity supply hours continued to worsen.

On December 28, 2014, ISIS made its first raid on the radio station. Mahmoud Al Suwaid, a member of the editorial staff, recounted that they broke in, kidnapping some colleagues and confiscating equipment, forcing them to stop broadcasting for a significant period. The radicalization of the conflict thus knocked on Kafr Nabl’s door, and radio workers feared that young people, immersed in an environment of war and instability, might lose faith in peaceful and democratic political voices. For the radio founders, promoting messages of non-violence was essential to prevent a new generation from taking up arms and perpetuating the cycle of violence, forming “the second and third editions of Daesh”, as the director explained.

However, the new media groups, activists, and writers were under fire from ISIS since their arrival. Many of them ended up being kidnapped or killed.

Journalist Zaina Erhaim explained how the radicalization of the conflict had affected the way journalists moved within Idlib governorate. A year earlier, they used to claim to be ‘media’ to avoid questioning and pass freely through an area. By the end of 2013, many new journalists were hiding their equipment, declaring themselves ‘locals’ for the same reason. Furthermore, Erhaim emphasizes that the first to be affected by these transformations were female journalists.

"I was wearing a headscarf at the request of a friend, Omar, who accompanied me. But when we arrived at the square, Raed asked me why I was wearing it. I told him that I was forced to by Omar, to which he expressed shock. “Asho [What]! Don’t listen to him! Take it off and those who dare to question your personal freedoms here have to deal with me. I am a ‘arsa; you don’t know me yet.” […] I took my headscarf off, and we paused for a souvenir picture that shows Omar embarrassed and Raed giggling.

One of ISIS’s last attacks targeted the director. In the early hours of January 29, 2014, after finishing his work shift, Raed Fares parked his car in the alleyway near his house. Two armed men approached and fired about fifty AK-57s rounds, leaving his car and the wall behind him riddled with bullets. Three bullets struck him, shattering several bones in his shoulder and some ribs, and puncturing his right lung. The director, recalling that moment, before being rescued by his wife and children and rushed to the hospital by his brother, wrote:

"As I lay bleeding, I felt death embrace me. I did not call for help, for fear the gunmen would return, but as I bled, I wondered what sort of twisted individuals would need to kill others to prove that they were right. No, I thought, only God has the right to remove me from life — and God ultimately saved me from their treachery".

Zaina Erhaim was still in Syria at the time, in a town near Kafranbel, Maarat al-Numan. She went to visit Raed Fares in the hospital, where dozens of men had crowded in and out of the building to see him.

She wrote:

"When he saw me, he laughed, with some pain showing in his features, and said, “I am recovered now. The most important journalist in Idlib is visiting me. There is nothing more I want. I am ready to be shot at again. What do you want to drink?"

I tried throughout the visit to persuade him to leave Syria, even for a short while, but it was in vain.

After the attack, Raed Fares took four months to recover. “I still have trouble breathing”, he later said, “but my doctor says my lungs shouldn’t have any problems, thanks to the size of my nose”.

Why is Russia bombing Kafr Nabl?

Subsequently, on two occasions, terrorists hid bombs under the director’s car. In 2014, however, ISIS’s rise to power in Kafr Nabl came to an end, giving way to the Al Nusra Front. In the meanwhile, foreign intervention in Syria, mainly directed at the threat posed by ISIS, escalated.

In this context, Raed Fares writes in 2015 the article “Why is Russia bombing my town?”:

While Russian President Vladimir Putin claims that he is bombing Islamic State “terrorists” in Kafranbel, this cannot be true, or there is no way I would be able to move about freely.

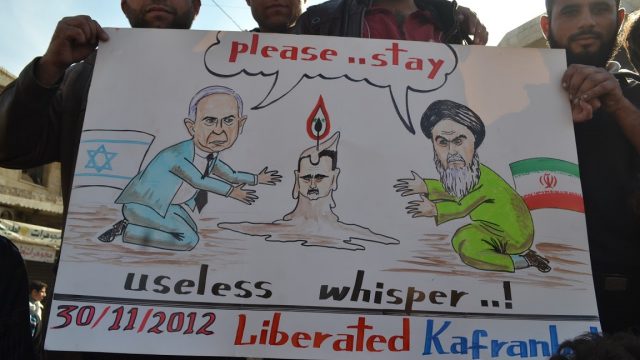

Meanwhile, civil society in Kafr Nabl continued to take to the streets, challenging the oppression of the regime and the Russian army. With banners and demonstrations, activists denounced hypocrisy and documented crucial events. Emblematic episodes included the citizens’ protest alongside FSA fighters and the demonstration against Russian bombings. The latter was filmed by Raed Fares and published on his YouTube channel. At the beginning of the video, Hammoud Jounin can be seen setting fire to a Russian flag as a symbol of protest, and behind him is Kafr Nabl’s distinctive banner.

This strong presence of civil society was precious but not a given, as Raed Fares repeatedly underlined. If, the journalist mused, activism in Kafr Nabl waned in the future, the Russian military would be responsible:

One of the reasons for our thriving civil society is that we are defended by FSA fighters, who grew up in the town and are firmly committed to democracy. These fighters, who have received U.S. assistance, serve as a check on any extremist groups that try to cause trouble. Russia is heavily bombing the pro-democracy fighters of Kafr Nabl most heavily, almost as if it wants the extremists to grow stronger. For this reason, Russia has emerged as an enemy of civil society here. […] Americans should not be so passive in the face of Putin’s farcical anti-Islamic State campaign. Kafr Nabl’s thriving civil society is in many ways modelled after that of the United States, and in some cases has even received US funding. Putin long ago made clear that he is no fan of civil society in general, so when he assaults the free people of Kafr Nabl (or Ukraine), Americans should take note. I hope that the American people will come to the defence of Kafr Nabl and all Syrians who are fighting for democracy, because their country’s current behaviour, as a bystander to atrocities against free people, cannot be a true reflection of what the United States stands for.

Meanwhile, groups of emerging journalists in Idlib and the rest of Syria gathered to defend their achievements. After fifty years of lack of independent information, culminating in the 2011 revolution, the need for structures, methods, and ethical standards was imperative. It was this awareness that led to the creation of the Ethical Charter for Syrian Media in 2015 , signed by 26 emerging independent media outlets. Two Radio Fresh delegates attended the signing of the Charter in Jordan. Fouad Roueiha, an Italian-Syrian journalist present at the event, during an interview described them as very young and enthusiastic not only about the Charter but also because it was the first time in their lives they had set foot outside Kafr Nabl.