The lock was broken. The door violently flung open. I heard their footsteps as they came up the stairs before they barged into my room. I thought I was dreaming, but I realized otherwise when one of them poked me with the tip of his AK47. “Get up!” he commanded.

When I opened my eyes, there were over ten armed men with ski masks on who surrounded me, demanding I go with them. My parents tried to figure out what was going on, but everyone was scared. They had mistreated every member of my family, beating them and calling them names before destroying the furniture.

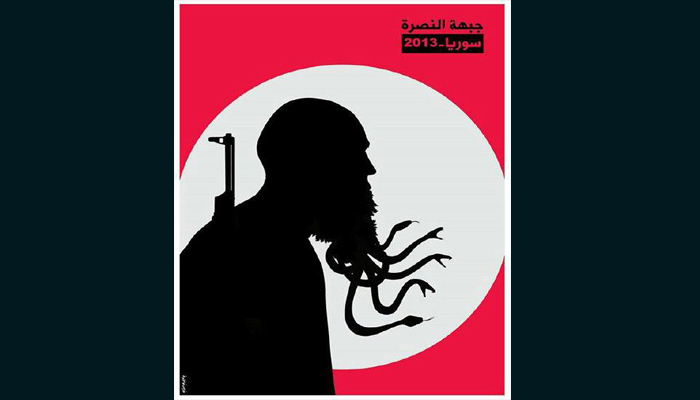

I still recall them calling me and my family infidels, and that’s when I realized they were Nusra Front members. I quickly got dressed and left with them before they could further insult my family, and before they could search the house to find my phone and laptop - both on which I had saved many articles and investigative journalism pieces against them.

They blindfolded me in the car, and I was driven to the Okab Prison, one of the most notorious prisons in the area. It was August 27, 2018 at 2:00 AM.

The silence was suspicious. It was dark and narrow, and it smelled foul. I was overwhelmed with thoughts, fears, and questions: What was my charge? What did I do? What will they do to me? What will my fate be at the hands of those men?

I couldn’t tell if the sun was up or not, and I couldn’t figure out where I was. It was a half-hour drive and I blindfolded on that trip, which meant I couldn’t figure out my bearings. Hours went by. I started getting hungry and thirsty. I knocked on my solitary cell door, calling for someone to open up so I could use the bathroom. But no one answered. There were moments during which I felt I was in a grave, buried alive and left for dead. Hours stretched. All I hoped for was to be allowed to use the bathroom so I wouldn’t have to relieve myself in the same tiny place where I was locked in.

After what seemed like a day, a man came to give me a piece of bread through the small door vent. I begged him to open up so I could use the bathroom. My bladder felt like it was about to explode. His only reply was “shut up.” I told him I wish to wash myself to be able to pray. Only then did he allow me out of the cell. “You have two minutes,” he said. “I’m waiting for you outside the bathroom door.”

As promised, he unlocked the door and led me through a narrow, dark passage. He shouted, “Go on. Be quick.” He had a strong-built and wore a military uniform, while covering his face. I could barely make him out in the dark.

I quickly performed ablution, preparing myself for prayers. Once he had me back in the cell, he said, “Don’t you dare make any more noise, or we will have to do something about it.” “Why am I here?” I asked. “What do you want from me? I didn’t do anything!” “Don’t worry,” he said. “You will know everything later.”

Another day went by. I couldn’t tell if it was day or night, as if I were in a real grave. I felt I was going to run out of air in that tiny place. Finally, I was taken to see the interrogator.

“I don’t look at their religion, but at the fact that they’re innocent Syrian civilians,” I replied.

He sat at his desk. With his long beard and unkempt hair, he gave an air of simplicity. He asked me to sit down, so I did. “What did you do?” he asked. “I didn’t do anything,” I said. He interrupted, screaming: “You go to protests demanding the release of the prisoners of As-Suwayda – those Druze infidels – and you say you didn’t do anything. It’s bad enough that we turn a blind eye to journalistic work with infidel channels and magazines, and you go as far as protesting to demand [the release of] the kidnapped of As-Suwayda.”

“I don’t look at their religion, but at the fact that they’re innocent Syrian civilians,” I replied.

He motioned to the armed man standing next to me, and I felt a fist meet my face. It hurt even more on the inside, because it hurt my pride. Silence fell. “Fuck you and your silly ideas,” he said.

This time, they didn’t take me back to the same solitary cell. Rather, they led me to one of the rooms were prisoners were being tortured, were being held in stress positions, and were lashed. There, I was insulted and beaten up. They used to call the detainees “infidels,” and their most lenient method of torture was lashing. Or maybe that’s what I thought. I found the stress position of “the ghost” - where you are hung by your wrists - to be so hard that it’s indescribable. It was as if the pain resembled the one you’d have if your hands were amputated and your body broken. Or maybe that’s how I felt after being hung in the “ghost” position for over three hours. Other methods of torture included using electrocution and water boarding. Thank God I survived both.

After more than three hours, I was transferred to another cell. It took was dark, narrow, and smelled foul. I could sense there was someone else next to me. When the guard left, I called out: “Is anybody there?”

Indeed, someone answered me. He said there were many others who have been incarcerated in small cells. We could not see each other due to the overwhelming darkness, but our conversations gave us some solace, even if despair was evident in our chats.

I was surprised to discovered that many of my friends who had been a part of that same demonstration were now in prison. It seemed as if everyone who helped organize the protest was arrested.

I asked the prisoners there how long they’d been there. One said a month, the other said 15 days. Another said over three months. I thought to myself: “Oh god. I can’t take it for a day, how will I bear three months or more?” It was a question that haunted my every waking moment.

Unclear charges

When I asked them about their charges, everyone had a different answer. Some had been vocal against the Nusra Front, others targeted them in satirical fliers, and some had stopped going to the mosque and closing their shops at times of prayer. Some were imprisoned because they refused to pay taxes to them. But the funniest thing in those hard times was that one was imprisoned for his modern-looking haircut. Indeed, as the saying goes, “The worst misfortune is the one that makes you laugh.” We were so deep in despair, while they mistreated us and toyed with us as they wished. What freedom was this if we were mere puppets in the hands of these fools?

I was certain that their rule and tyranny will come to an end one day, as has been the case for many tyrants before them. We are a people who had suffered and who still do in their quest for freedom, and it comes at a hefty price.

When I was in prison, I blamed every faction, every organization, and every party that had worked with the Nusra Front. This was the only reason they were able to continue inflicting their injustices against us, causing us pain. The Assad regime, its allies and its fire power from the skies just weren’t enough. We now have to endure those people who were doing what the Assad forces weren’t able to carry out in our areas: injustice, tyranny, terrorism, arbitrary arrests…

I spent a little over a month in that shitty cell. It’s true that I wasn’t tortured on a continuous basis during that time, but just being there was enough to deal a hard blow – a sort of physical and psychological torture.

Out of the frying pan

Before I was released, the interrogator ordered me to stop my work, including anything that has to do with journalism and the media. He threatened me, saying that if I do not comply, I will face a different kind of punishment. “We haven’t done anything to you yet. You staying here for this period was a message, which, I hope, you have understood. Or you would force us to use a completely different kind [of punishment] with you. It’s a kind that I don’t believe you’d be able to handle, that is, if you stay alive,” he said.

The interrogator’s threat made me stop practicing my journalistic work publicly. With extreme caution, I continued to keep an eye on my interrogator within my area, which I had – mistakenly – believed =was liberated. It was only then that I learned of an entirely different truth, to which now I can only quote the popular saying, “Out of the frying pan and into the fire.”